Michael W. Taylor

How much of the fatal policy of states, and of the miseries and degradations of social man, have been occasioned by the false notions of honor inspired by the works of Homer, it is not easy to ascertain … My veneration for his genius is equal to that of his most idolatrous readers; but my reflections on the history of human errors have forced upon me the opinion that his existence has really proved one of the signal misfortunes of mankind.

Joel Barlow, Preface to The Columbiad (1809)

In the cold and somewhat troubled winter of 1974–1975 in Cambridge, Massachusetts, a group of young scholars including Gregory Nagy, Douglas Frame, Steven Lowenstam and myself met one evening a week to discuss Homer and to read our current work aloud to each other. [1] It was a great privilege, and it was in that setting that my 1975 Ph.D. thesis, The Tyrant Slayers: The Heroic Image in Fifth Century B.C. Athenian Art and Politics evolved. We styled ourselves the Homer Club, and, mainly, it was a lot of fun. That always seemed to be one of Greg’s main goals, to make sure we enjoyed the study of Homer and Homeric language. I learned this about Greg at the first graduate student party I attended at his apartment when he told us how much he liked the movie, “Jason and the Argonauts.”

That winter of 1974–1975 was a period of political uncertainty following the resignation of Richard Nixon. There were severe economic troubles that followed in the wake of the Yom Kippur War and the Arab oil embargo. The final tragic chapter of the war in South Vietnam and Cambodia — in which I had served as a naval officer — was taking place. The Turks had overrun the excavation site at which I had worked as a field archaeologist with Emily Vermeule in the previous summer, and there had been looting of the dig finds (over which members of the excavation team including myself had labored many hours) that were stored in the apotheke of Agios Mammas Church in Morphou. The academic job market seemed almost non-existent. But despite the prevailing troubled atmosphere, Greg Nagy kept our attention focused on the language of Homer and kept asking about the transcendent meaning of the words. And he never discouraged, but instead encouraged and urged on the thinking processes and ideas of a lowly graduate student.

I came to my subject after spending the 1973–1974 school year as the Charles Eliot Norton Fellow at the American School of Classical Studies in Athens. It was my good fortune that one of the resident scholars that year was Evelyn Harrison of New York University who generously gave her time in discussing with me my nascent ideas about the context of late Archaic and early Classical Athenian sculpture. Her comments on the Athena Parthenos as we stood before the small copy in the Patras Museum on a School trip helped me formulate my ideas about the iconography of the Athenian state.

In recent years, I have gained the insight that my ideas about the religious usage of the tyrant slayers as founding heroes of the Athenian democracy were influenced by my childhood spent as the son of Southern Baptist missionaries living amongst the Yoruba in what was then the Western Region of the British Protectorate of Nigeria. My father, a Duke University Ph.D. in Southern History, taught history at Iwo Baptist College (now Bowen University in Iwo, Nigeria). He often reminded me of the parallels between the Greeks and the Yoruba, both living in city-states and both worshipping a pantheon of deities. As a child, I sometimes came upon a dish of food set before a painted rock as I explored the bush around our mission station and often saw women of the town praying for fertility before a giant baobab tree around which strips of cloth were tied. From these experiences, I came to understand how a propitiatory religion works, and in retrospect looking back years later, I can see that I applied that understanding to the tyrant slayers.

My desire to be an archaeologist was greatly influenced by my historian father, but I did not need much pushing in that direction after visiting the ancient ruins of Africa, the Middle East and Europe in my childhood and early teenage years. I owe a great debt to my parents, Orville W. Taylor and Evelyn B. Taylor, for the gift of a love of learning and the opportunity to explore our past.

My interest in the Athenian democracy was triggered while I was still in high school by a lecture that I attended at UNC-Chapel Hill in the early 1960s given by Anthony Raubitschek on Athenian ostracism. And my understanding of the threats that democracy could face and the citizen efforts that could be undertaken to oppose those threats was informed by the fight against the Speaker Ban Law at Chapel Hill during my undergraduate years and by the events of the Watergate scandal.

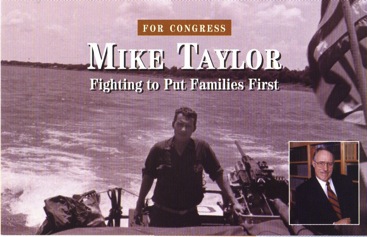

Certainly, my visceral and partially negative reaction to the reckless daring of the tyrant slayers and its destructive possibilities was influenced by my military service in the Vietnam War. The insouciance of youth could not survive sights such as the bodies of massacre victims I saw floating down the Mekong River when I rode a Swift Boat upriver into Cambodia during President Nixon’s May 1970 incursion.

Lt.(j.g.) Michael W. Taylor on Swift Boat going up the Mekong River in Cambodia, May 1970.

1998 political campaign use of photograph above.

But my presence in Athens, Greece, on November 17, 1973, when the Junta crushed the student demonstration at the Polytechnion gave me a renewed admiration for opponents of tyranny when I witnessed uniformed officers knocking a bearded young man to the pavement and savagely beating and kicking him as the crowd began to run up Kolonaki, heard from my room at the American School the rumbling of tank treads on the streets and machine gun fire echoing across Athens during the night, and then saw the destruction at the Polytechnion and its environs the next day.

I began my research in the summer of 1974 in the library of the Fogg Art Museum in trying to understand why Theseus was being depicted in the tyrannicide poses. I collected all of the vase paintings of Theseus that I could find and lined them up chronologically. This is the research work that produced Chapter 4 of my book. As it became clear to me that the dating of the shift in the portrayal of Theseus to the tyrannicide pose coincided approximately with the reforms of Ephialtes in the late 460s and the ascent of Pericles to power, I realized that I had found what I was looking for, a nexus of evidence for understanding the spirit of the Athenian democracy at its high summer. Because of the course in Greek Lyric Poetry that I had taken from Gregory Nagy, I was able to grasp early on that my basic theme had a Homeric and Nagy-ian quality to it, and was at essence about the Athenian quest for kleos aphthiton — undying fame. This is a perilous matter, it turns out. Great things can be accomplished with immense self-confidence, but reckless daring also to leads to destruction.

An enticing aspect of the subject of Harmodios and Aristogeiton was the wide variety of the evidence, literary, historical, epigraphical, numismatic, sculptural and pictoral. When I was writing my Ph.D. thesis in 1974–1975, I could find precedent for neither the multidisciplinary approach I was using perforce, due to the nature of the evidence, nor for my ideas about the tyrant slayers playing a religious role in formulating a refoundation of the Athenian state. Alan Shapiro’s review in Journal of Hellenic Studies, vol. 113 (1993), pp. 211–213, complimented that approach, and I have always been grateful for that review.

As I did my research back then, I came to visualize scholars in a variety of walled-off enclosures working in his or her own field — philology, ancient history, political philosophy, archaeology, art — and his or her own set of evidence — the statues, the drinking songs and the references to them in Aristophanes, the laws about the descendants, the passages in Herodotus and Thucydides — with each scholar laboring on his or her own projects in isolation, almost as if they saw themselves as not being allowed to proceed to find the overarching meaning of their work, perhaps through a too-zealous application of time-honored narrow and restrictive customs of Classical scholarship, put in place long ago to assure the focus on detail and accuracy required for excellence in this field.

As a graduate student, I was always encouraged to view German scholarship as a great model for emulation, so when I found only a short article on the tyrant slayers in the Pauly, I realized that I might have stumbled on a piece of Greek history that had not yet been thoroughly studied, and I was off and running. It seemed to me that all of the evidence about the tyrant slayers — historical, literary, epigraphic, numismatic, sculptural and pictorial — cried out for a multidisciplinary interpretation. I felt at the very least I could make a contribution (modeled on Brunsåker’s most useful compilation of fragments of copies of the tyrannicide statue group) by collecting together in one volume citations to every historical, literary, epigraphic and visual art reference to Harmodios and Aristogeiton that I could find. And I also set out to collect vase paintings of the Labors of Theseus in an effort to understand the phenomenon of a mythological king being refigured to imitate historical democratic heroes in red figure Athenian vase painting depicting Theseus standing in the poses of the tyrannicides. My book, The Tyrant Slayers, was basically the result of asking a question — Why did Theseus appear as a tyrannicide in Athenian vase painting? — and collecting evidence to attempt to answer that question.

Before The Tyrant Slayers, scholarship on the Athenian tyrannicides remained fragmented. The Tyrant Slayers collocated historical, epigraphical, archaeological, art historical, and literary sources, [2] crossing disciplinary boundaries in order to achieve a fuller understanding of how and why Harmodios and Aristogeiton came to be regarded as tyrannicides in the first place, [3] and what their commemoration signified to ancient Athenians; as my 1991 introduction puts it, “[H]ow did the Athenians imagine their democracy?” [4] This question has captured the interest of subsequent scholars, who rely upon The Tyrant Slayers when discussing the tyrannicide tradition in particular and Athenian democracy in general. [5] The Tyrant Slayers’ primary theses have been incorporated into detailed and focused discussions of various aspects of Athenian democratic culture, and have gained the support of fruitful application. [6]

Where do we go from here with Harmodios and Aristogeiton? What more does the phenomenon of the tyrant slayers have to tell us about Athens — and about ourselves, about our own 21st century concepts of democracy and the state? What has been missed?

In writing this, I have the advantage of returning to Classical scholarship after an absence of more than three and a half decades while I have practiced law, been engaged in politics and, as an avocation, read the Classics and American and English history on the side along with writing and publishing books and articles about the American Civil War. I am now able to look at my work and the scholarship that uses it with a fresh perspective. The main issue that needs to be further studied, I believe, is a point I attempted to make in the original 1975 Introduction to my Ph.D. thesis that became a part of the 1981 edition of The Tyrant Slayers: the central significance of the religious (civil religious, if you will) aspect of the commemoration of Harmodios and Aristogeiton.

Future Work to Be Done on the Tyrannicides? It’s Time to “Get” Religion and Understand Propaganda

We live in a time when propaganda, much of it of religious and particularly civil religious in nature, permeates our lives through the airwaves. I fully believe that the power and effect of the propaganda being directed at us cannot be fully understood without an appreciation of the impact of its religious component. From only brief recent observation of the current academic scene, but also from my knowledge of the society surrounding it, I have come to postulate that we live in a time when it is very difficult for scholars with standing within the Academy to acknowledge and accept the power of the religious experience without at the same time belittling that power as mere superstition. Some scholars, very understandably, tired of being attacked as God-less secular humanists, tend to react by discounting and even disdaining the genuine impact and emotional power of religion, giving little credence to the religious instinct. [7]

As an antidote to such scholarly thinking I believe it is time to renew an acquaintance with the critique of unbelief set forth in William James’ 1896 lecture, “The Will to Believe” in which James mocks atheism and agnosticism as “the queerest idol ever manufactured in the philosophic cave”:

Were we scholastic absolutists, there might be more excuse. If we had an infallible intellect with its objective certitudes, we might feel ourselves disloyal to such a perfect organ of knowledge in not trusting to it exclusively, in not waiting for its releasing word. But if we are empiricists [pragmatists], if we believe that no bell in us tolls to let us know for certain when truth is in our grasp, then it seems a piece of idle fantasticality to preach so solemnly our duty of waiting for the bell. [8]

During my first semester at Harvard in the fall of 1971, Professor Edith Porada was a visiting scholar from Columbia University. After hearing her lecture on cylinder seals, I asked her one of those first year graduate student questions, “What is the origin of art?” She proved herself to be a very kind person and answered me without scorn or irony, “Oh, art comes from religion.” (Or words to that effect, as best I can remember.) So, once again, the power of the religious experience manifests itself not just in emotions but in tangible ways through art which in turn has emotive power.

It is now approaching 150 years since Matthew Arnold recorded the “melancholy, long, withdrawing roar” of the “Sea of Faith” in his poem, “Dover Beach,” and that withdrawal seems to have accelerated. We may not be as adrift religiously as much as a character in a Douglas Coupland story in Life After God (Pocket Books, 1994), but the Coupland stories are on target enough to make many Amazon.com reviewers confess to the stories’ accuracy. In the present secular environment, it difficult for us to understand the Athenians’ religion, even 60 years after the publication of E.R. Dodds’ seminal work, The Greeks and the Irrational (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1951).

It is not very surprising, then, that scholarship touching upon the tyrant slayers over the past 37 years has given little attention to the religious aspect of Harmodios and Aristogeiton, too little in my opinion. It is critically important to remember that the Athenians of the classical period were a very religious people, even when beginning to address the sometimes apparent dichotomies of faith and reason.

Robert Parker in his study of Athenian religion points out that even Socrates and Plato were bested by traditional religion, or at least, in Plato’s case, accommodated it. Parker highlights Plutarch’s story of Dion’s entourage, graduates of Plato’s Academy, being unalarmed by an eclipse but offering an encouraging explanation to the troops through the seer, Melitas, and Parker notes, “The formal victor was certainly traditional religion.” [9] But while noting that I stress in my book “the Athenian tendency to assimilate tyrannicides to war-dead,” Parker does not go much further in discussing what this might mean. [10] One might have hoped for much more from such a learned scholar in such a magisterial work. [11]

It may be that civil religion is in a category all by itself when it comes to producing emotions of a violent nature, perhaps because the machinery of the State is available to those so emoted so that they can sometimes wreak vast swathes of destruction. One has only to think of film footage of torchlit Nazi rallies at Nuremburg to understand the extremes to which those emotions can be taken. The images of civil religion, like those of Harmodios and Aristogeiton, can seem to elevate when they actually serve to soften and even falsify our understanding and memory of the horrors of war and violence.

A central postulate of my 1975 Harvard Ph.D. thesis on the tyrant slayers was that it was Pericles who seized upon Harmodios and Aristogeiton as a central symbol of the radical Athenian democracy that he led in putting forward, beginning around 460 B.C.E. It seems that Pericles, as a brilliant politician, understood the importance of propaganda in a democracy.

The very term, “propaganda,” has pejorative connotations of manipulation, deceit, and inequality. [12] We commonly reserve the word for cultural products and social meanings that we find problematic. [13] However, it is essential that we come to understand how and why propaganda is so important in a democracy and how it can be destructive of the essential character of the democracy in stifling dissent, particularly when the propaganda takes on religious overtones implying that true adherents of a particular religious orientation must vote a certain way, regardless of what their reasoned judgment might tell them.

The power of propaganda is frequently underestimated by idealists who fail to see, until too late, the ways it can be used to manipulate the public. [14] Clearly, modern American and European history offers many examples of the power of propaganda. By looking back at the experience of the Periclean democracy and then forward at examples in our more recent history, we can gain a deeper understanding of propaganda and see that its use from ancient times to modern forms one continuum of the same phenomenon. Jacques Ellul has pointed out that when a democracy has appeared, propaganda has historically established itself alongside it. “This is inevitable, as democracy depends on public opinion and competition between parties to gain power. In order to come to power, parties make propaganda to gain voters.” [15] But Ellul, who fought with the French Resistance against the Nazi occupation of France, makes a cautionary observation:

… [I]t is evident that a conflict exists between the principles of democracy — particularly the concept of the individual — and the principles of propaganda. The notion of rational man, capable of thinking and living according to reason, of controlling his passions and living according to scientific patterns, of choosing freely between good and evil – all this seems opposed to the secret influences, the mobilizations of myth, the swift appeals to the irrational, so characteristic of propaganda. [16]

In an incisive analysis very pertinent to the Athenian democracy’s symbolic uses of Harmodios and Aristogeiton, Ellul says:

[A]ny operation that transforms democracy into a myth transforms the democratic ideal. Democracy was not meant to be a myth … [D]emocracy cannot be an object of faith, of belief: It is an expression of opinion. There is a fundamental difference between regimes based on opinion and regimes based on belief. To make a myth of democracy is to present the opposite of democracy. One must clearly realize that the use of ancient myths and the creation of new ones is a regression toward primitive mentality, regardless of material progress … [T]he objects of propaganda tend to become totalitarian because propaganda itself is totalitarian … [S]uch propaganda can be effective as a weapon of war but we must realize when using it we simultaneously destroy the possibility of building true democracy. [17] (Emphasis added)

Within Athens and as an adjunct to compulsion within the Athenian Empire, propaganda was critically important to the execution of the policies of Pericles. In Harmodios and Aristogeiton, I would contend, Pericles found an ideal focus for his propaganda. The question must be whether Pericles used this propaganda for democratic or anti-democratic purposes.

How can we gain an in-depth understanding of the phenomenon of the Harmodios and Aristogeiton as powerful symbols of the radical Athenian democracy? Useful analogies can be found in modern American and European history. The power of propaganda to influence the citizens of a democracy to make an about face and go in a direction chosen by the state has been taken to possibly unimagined new levels in the modern age, and propaganda’s power is illustrated by several well-known events of the past two centuries of modern history. [18]

Periclean Athens and American Democracy

It should be noted at the outset that the power of propaganda in the form of demagoguery in a pure democracy was much feared by the American Founders. It is clear that they looked with horror and revulsion on the example of the Athenian democracy as a recipe for mob rule and cataclysm. [19] The example of the Roman Republic was looked upon favorably, but the skepticism in the early American Republic toward things Greeks is illustrated by a statement made by Joel Barlow, author of the American epic poem “The Columbiad” (1809), who expressed his belief that the survival of the text of Homer was “one of the signal misfortunes of mankind” because of “the false notions of honor inspired by Homer.” [20]

Jennifer T. Roberts in a useful and fascinating article traces the rising and falling fortunes of the contrasting portraits of Pericles by Thucydides and Plutarch in America (and in England). A review of the views of Pericles tracked by Roberts shows not only how those opinions changed in America from the early Republic to the Civil War, but also reveals the conflicting truths about one of the greatest democratic heroes in history, a true “traitor to his class” [21] who was a champion of the people and of pure democracy but also the leader whose aggressive foreign policies led to overextension and ultimately to defeat.

In the 18th century, culminating in Alexander Hamilton’s attack in the Federalist Paper no. 6, Pericles was seen as a greedy, corrupt and power-hungry leader who plunged Athens into a disastrous war with Sparta in order to distract the Demos from seeking to prosecute him. This changed in the 19th century as early as 1803 when Hamilton, under the pseudonym “Pericles,” urged America to become an imperial power. Such a shift may have been seen as possible once the basic structure of the American constitutional government had been established on the basis of a divided balance of power. [22]

The 19th century rise in popularity of a beneficent view of the Greek polis was reflected in Greek Revival architecture and the establishment of the first professorial chair in Greek at Harvard in 1817, filled by Edward Everett in 1819, followed by Yale’s chair in Greek established in 1831 and filled by Theodore Woolsey. Both Everett and Woolsey later became President of their respective universities.

William Mitford’s eight volume History of Greece, published between 1784 and 1818, espoused a negative view of Pericles and of Athens: “[T]he Athenian people were the despotic sovereign; Pericles the favourite and minister, whose business it was to indulge the sovereign’s caprices that he might direct their measures; and he had the skill often to direct their caprices.” [23]

Thomas Babington Macaulay wrote a scathing review of Mitford’s history and called for a new history of Greece that would “celebrate Athens as the cradle of philosophy and the arts,” according to Roberts. Macaulay showed his true colors by displaying an intense enthusiasm for Athens in an essay entitled, “On the Athenian Orators” that, according to Roberts, “glorified Pericles and his age in a rapture of ecstasy”:

We enter the public space; there is a ring of youths, all leaning forward, with sparkling eyes, and gestures of expectation. Socrates is pitted against the famous atheists of Ionia, and has just brought him to a contradiction in terms. Pericles is mounting the stand. Then for a play of Sophocles, and away to sup with Aspasia.

Macaulay concluded that he knew of no modern university that had “so excellent a system of education.” Roberts comments dryly, “One cannot help wondering exactly how Aspasia fit the Athenian demos at her table. . .” [24] And yet, as one stops for a moment to smile at Macaulay’s 19th century expression of English enthusiasm for Athens, one cannot help but note that there is something of validity in Macaulay’s admiration for debate in the public space which lies at the beating heart of true democracy. [25]

Harvard Greek Professor and President Edward Everett was influential in several areas including the American movement that began in Mount Auburn Cemetery in Cambridge, Massachusetts to make cemeteries into something like parks or nature preserves. Everett’s most famous moment came in November 1863 at the dedication of the national cemetery at Gettysburg, where he referred to Pericles’ Funeral Oration and spoke for two hours before Lincoln gave his immortal “brief remarks,” known to history as the Gettysburg Address.

Everett’s two hour speech at Gettysburg has not been treated very kindly and is hardly ever mentioned except for its great length. But it was in fact in many ways a homage to Pericles’ Funeral Oration in Thucydides, albeit with words for bereaved women that Pericles refused to give. While Everett’s Gettysburg address is often compared unfavorably to Lincoln’s, Jennifer Roberts kindly takes note of Everett’s concern for women in his address (so unlike that of Pericles) and notes, “Everett’s Civil War appropriation of his Periclean/Thucydidean material, then, was thoughtful and creative, ringing important variations on the classical text.” [26]

From the Southern point of view, Confederate soldier and scholar Basil Lanneau Gildersleeve in his famous article, “A Southerner in the Peloponnesian War” Atlantic Monthly September 1897, 330–341, dismissed Plutarch’s negative portrait of Pericles as of little value: “The Southerner resented Northern dictation as Pericles resented Lacedaemonian dictation, and our Peloponnesian War began.” [27]

Although the image of Pericles shifted to a more beneficent one as the 18th century wore into the 19th, the history of the American Civil War and subsequent conflicts shows that propaganda — which I believe Pericles wielded very effectively — has become only more prevalent, with its practitioners more skilled and, as a result, propaganda is even more dangerous than it ever was. Modern events, especially wars which call for especially intensive propaganda efforts, offer useful historical analogies for the study of the Classical period in Athens in general and of the motivating emotions offered by the tyrant slayers in particular.

The tyrant slayers offer a fruitful subject for understanding the uses and abuses of propaganda, particularly with civil religious overtones, and the striking parallels with modern American and European history can inform our understanding of both periods of history and of our own present situation, besieged as we are with propagandizing messages pouring in over the air waves.

It is often difficult to believe that modern soldiers have been willing to sacrifice themselves voluntarily in scenes of such great carnage as presented by warfare waged by modern industrial states. The motivating factors must be understood, and paramount among those factors is propaganda. At the same time, it is extremely interesting and encouraging to see that poets and other artists have chosen at critical moments both before, during and after wars to question and speak out against the prevailing national tides of propaganda that unleashed such violence, even though, as World War I English war poet Wilfred Owen, who died in the fighting only a week before Armistice Day 1918, observed, all a poet can do today is warn. [28]

Democratic propaganda and the battlefields of the American Civil War

The American Civil War was a cataclysm of extreme violence and loss that brought freedom to the slaves and along the way also forged the modern American state, introducing such measures as military conscription, the income tax, huge prison camps in which inmates perished by the thousands, suspension of habeas corpus, trench warfare, and industrial slaughter of soldiers on a scale so massive that the true total of losses are even now mere estimates and historians have yet to write comprehensive scholarly histories of some entire campaigns. [29] In the years of fighting and those that followed, poets such as Walt Whitman and Herman Melville spoke about the true cost of the War. Visual images were created in media new and old, from paintings and drawings to photographs which portrayed the War’s true appearance, causing uneasiness on the home front, just as the televised images of fighting in Vietnam disturbed American civilians 100 years later.

As Daniel Webster had predicted in an 1850 speech replying to those who argued that secession could be peaceable, the American Civil War was a climactic and very nearly apocalyptic event:

Peaceable secession! Sir, your eyes and mine are never destined to see that miracle. The dismemberment of this vast country without convulsion? The breaking up of the fountains of the great deep without ruffling the surface? Who is so foolish … Sir, I see as plainly as I see the sun in heaven … that disruption … must produce war, and such a war as I will not describe. [30]

The events of 1861–1865 are replete with examples of uses, abuses, and means of deployment of plastic and verbal imagery as propaganda through which the harsh medicine of modern statehood was made palatable and, if necessary, force fed to the citizenry, just as the imagery of the tyrant slayers was used to inspire the citizens of the Athens with a love of their polis to attempt — and sometimes fail at — great things. As Herman Melville put it in his poem, “On the Slain Collegians”:

… what troops

Of generous boys in happiness thus bred–/

Saturnians through life’s Tempe led,

Went from the North and came from the South,

With golden mottoes in the mouth,

To lie down midway on a bloody bed.

Of generous boys in happiness thus bred–/

Saturnians through life’s Tempe led,

Went from the North and came from the South,

With golden mottoes in the mouth,

To lie down midway on a bloody bed.

The State with a sword summons to war a student who drops his books. Bronze bas relief on the base of “Silent Sam,” the University of North Carolina’s Confederate statue, memorial to the 321 UNC students who died in the Civil War. Photo by the author.

Those “golden mottoes” of the American Civil War included a Southern conviction that the fight was for liberty, despite the South’s “Peculiar Institution.” The result was the sight of a chorus of young women in South Carolina celebrating secession by singing the “Marseillaise.” [31] In the North, young men fought and died for the Union, but the shock of the horrors they encountered on the battlefield is evident in their letters and diaries. [32]

Antietam, Md. Confederate dead by a fence on the Hagerstown road. Image Credit: Library of Congress, Prints & Photographs Division, Civil War photographs, 1861-1865, LC-DIG-cwpb-01097.

Perhaps only the 170,000 African-American soldiers of the United States Colored Troops fought with such self-evident self-interest that they did not need to be inveigled into fighting by “golden mottoes.” In any event, the U.S.C.T. are credited by recent historians as having been a key factor in the final defeat of the Confederacy. Lee found his way out blocked by regiment upon regiment of black troops at Appomattox. [33]

Confederate memorial statue “Gloria Victis” in Salisbury, NC, depicting Fame lifting up a dying Confederate soldier, by sculptor Frederic Wellington Ruckstuhl, created 1891, dedicated 1909. Photograph by the author.

The strength and influence of civil religion, which is the true focus of the tyrant slayers’ phenomenon, is more easily appreciated and understood, perhaps, by a native of the American South, such as myself, who even at a remove of 150 years from the Civil War can still sense the impact upon my home region of the so-called “Lost Cause Religion” that permeated the Southern states for 50 years and more following the American Civil War. [34] In some ways, the Athenian fascination with the tyrant slayers and, by extension, with the Marathonomachoi and the heroes of the Persian Wars and the Trojan War, was paralleled by the self-identification of Southerners before, during, and after the American Civil War with the knightly heroes of chivalry. Mark Twain, who mocked the late 19th century obsession with chivalry in A Connecticut Yankee at King Arthur’s Court, even went so far as to lay blame for the Civil War upon the writings of Sir Walter Scott in Life on the Mississippi. The Southern fascination with medieval chivalry was so great that an edition of Jamison’s Life & Times of Bertrand du Guesclin (c.1320–1380), the Constable of France and “the most renowned captain of the Hundred Years War” [35] was published in Charleston, SC, in 1864 on wall paper. [36]

The American Civil War start to finish was a great arena for overheated rhetoric and a ferocious attachment to images and idealized leaders. The international campaign to abolish slavery involved a massive propaganda effort that was sped on its way by iconic works such as J.M.W. Turner’s painting, The Slave Ship, and Harriet Beecher Stowe’s novel, Uncle Tom’s Cabin under charismatic leaders like William Wilberforce, William Lloyd Garrison, Frederick Douglass — and, of course, John Brown. [37]

The South was well known for its pro-slavery fire eaters like South Carolina Congressman Preston Brooks who caned Senator Charles Sumner on the floor of the U.S. Senate and Virginia’s Edmund Ruffin who fired the first shot at Ft. Sumter and committed suicide when he received word of Lee’s surrender at Appomattox. [38] But it is easy at this remove to fail to understand the reaction sparked in the South by John Brown’s Raid and the radical abolitionist’s extreme violence in “Bleeding Kansas” hewing their pro-slavery neighbors into pieces with swords. The 2004 Pulitzer Prize-winning novel Gilead, by Marilynne Robinson in which the narrator recounts some of the history of his preacher grandfather who rode with John Brown in Kansas contains a fictional 4th of July speech by the grandfather in which he encapsulates the feelings of his generation that fought against slavery — and his words are not peaceable. The Grandfather recalls his vision as a young man of the Lord putting his hand on his right shoulder and giving him Jesus’ message of liberation preached in Luke 4:18 and taken from Isaiah 61:1. The Grandfather also goes on to castigate those who live around him in modern times, saying the young men no longer dream dreams and bemoans the present condition of the State of Iowa which Grant had once been called “the shining star of radicalism.” [39]

Others, with deeper insight, grasped the painful consequences of putting into action laudable ideals with “passionate enthusiasm,” as Oliver Wendell Holmes, Jr., described it in a second 1895 Memorial Day speech [40] that was said to have inspired Theodore Roosevelt.

Holmes makes an interesting case because his wartime letters clearly show disillusionment with the fighting, perfectly understandable given his three severe wounds. [41] After being severely wounded at the September 1862 battle of Antietam, Maryland, Holmes wrote home to his sister that “I have pretty much made up my mind that the South have achieved their independence. … I think before long the majority will say we are working to effect what never happens, the subjugation of a great civilized nation.” However, 20 years after leaving the Army he could describe his war service in an 1884 Memorial Day address in words that seem far from the harsh realities of combat:

[T]he generation that carried on the war has been set apart by its experience. Through our great good fortune, in our youth our hearts were touched with fire. It was given to us to learn at the outset that life is a profound and passionate thing. [42]

What is so amazing about Holmes’ words in his famous 1884 and 1896 Memorial Day addresses is that along with William James, Charles Peirce, John Dewey and others at Harvard, Holmes worked to avoid the horrific consequences of fanaticism and the heated rhetoric that accompanies it.

It took one of America’s greatest poets, Walt Whitman, to see the truth that lay behind the talk of glory. In his post-Civil War poem, “The Return of the Heroes,” Whitman wrote of seeing a vast military parade, a vision very likely based on the May 24–25, 1865, Grand Review of Grant’s and Sherman’s armies in Washington, D.C. [43] The New York Times of May 25, 1865, opined:

The last great scene of the war has closed. It has been everything that could impress the senses and stir the imagination. Every American who has seen it, or even read of it, has rejoiced in its “pride, and pomp, and circumstance.” His pulse has been quickened by all its heroic associations, and by all its suggestions of the might and majesty of the republic … We may declare almost positively that this American Republic will never again see such another array of armed men. That in itself would make this parade an occasion of transcendent mark. And yet how tame is the mere circumstance of numbers in this case. Who gives a thought to the bare fact that two hundred thousand soldiers have been reviewed in the National Capital? The thought that fills the mind is not how many soldiers; but what soldiers. Who would not rather see the three hundred of Thermopylae than all the millions of Xerxes?

Walt Whitman’s vision expressed in “The Return of the Heroes” went beyond the triumphant Grand Review to the reality he had seen as a Civil War hospital orderly, a pallid bleeding army of the conflict’s detritus:

But now I sing not war,

Nor the measur’d march of soldiers, nor the tents of camps,

Nor the regiments hastily coming up deploying in line of battle;

No more the sad, unnatural shows of war.

Ask’d room those flush’d immortal ranks, the first forth-stepping armies?

Ask room alas the ghastly ranks, the armies dread that follow’d.

(Pass, pass, ye proud brigades, with your tramping sinewy legs,

With your shoulders young and strong, with your knapsacks and your muskets;

How elate I stood and watch’d you, where starting off you march’d.

Pass–then rattle drums again,

For an army heaves in sight, O another gathering army,

Swarming, trailing on the rear, O you dread accruing army,

O you regiments so piteous, with your mortal diarrhoea, with your fever,

O my land’s maim’d darlings, with the plenteous bloody bandage and the crutch,

Lo, your pallid army follows.) [44]

Nor the measur’d march of soldiers, nor the tents of camps,

Nor the regiments hastily coming up deploying in line of battle;

No more the sad, unnatural shows of war.

Ask’d room those flush’d immortal ranks, the first forth-stepping armies?

Ask room alas the ghastly ranks, the armies dread that follow’d.

(Pass, pass, ye proud brigades, with your tramping sinewy legs,

With your shoulders young and strong, with your knapsacks and your muskets;

How elate I stood and watch’d you, where starting off you march’d.

Pass–then rattle drums again,

For an army heaves in sight, O another gathering army,

Swarming, trailing on the rear, O you dread accruing army,

O you regiments so piteous, with your mortal diarrhoea, with your fever,

O my land’s maim’d darlings, with the plenteous bloody bandage and the crutch,

Lo, your pallid army follows.) [44]

The Tyrant Slayer statues in the Agora upon their base inscribed with the short poem about a “great light” being produced for Athens [45] might seem far removed from the Lincoln Memorial on the Mall in Washington, D.C., with its enormous seated marble image of the Great Emancipator and the lengthy inscribed quotations from the Gettysburg Address and the Second Inaugural Address on either side. However, both monuments contain imagery meant to rally the democratic state to loyalty and action. The “great light” that the tyrannicide epigram proclaimed “was born for the Athenians” was precursor to “the new birth of freedom” resolved by Lincoln in the Gettysburg Address. The “new birth of freedom” that Lincoln saw actually took another hundred years and a Second Reconstruction to realize. And as the Civil War ended, the veterans who had borne the battle, to use Lincoln’s words in his Second Inaugural, were left to return home and put the war behind them. [46]

Democratic Propaganda and World War I

In the 20th century, the deployment of mythologized propaganda to inspire the democratic masses to fight reached a height in the First World War. The use of myth as propaganda played an important role in mobilizing the British, French and American democracies for war — in much the same way as Pericles’ use of propaganda did nearly 2400 years earlier

At the Great War’s beginning in 1914, the naiveté of those rushing off to war is heart breaking. There are many examples that can be cited, but none more telling than the British soldiers who charged into German machine gun fire at the battles of Loos and the Somme kicking a football. [47]

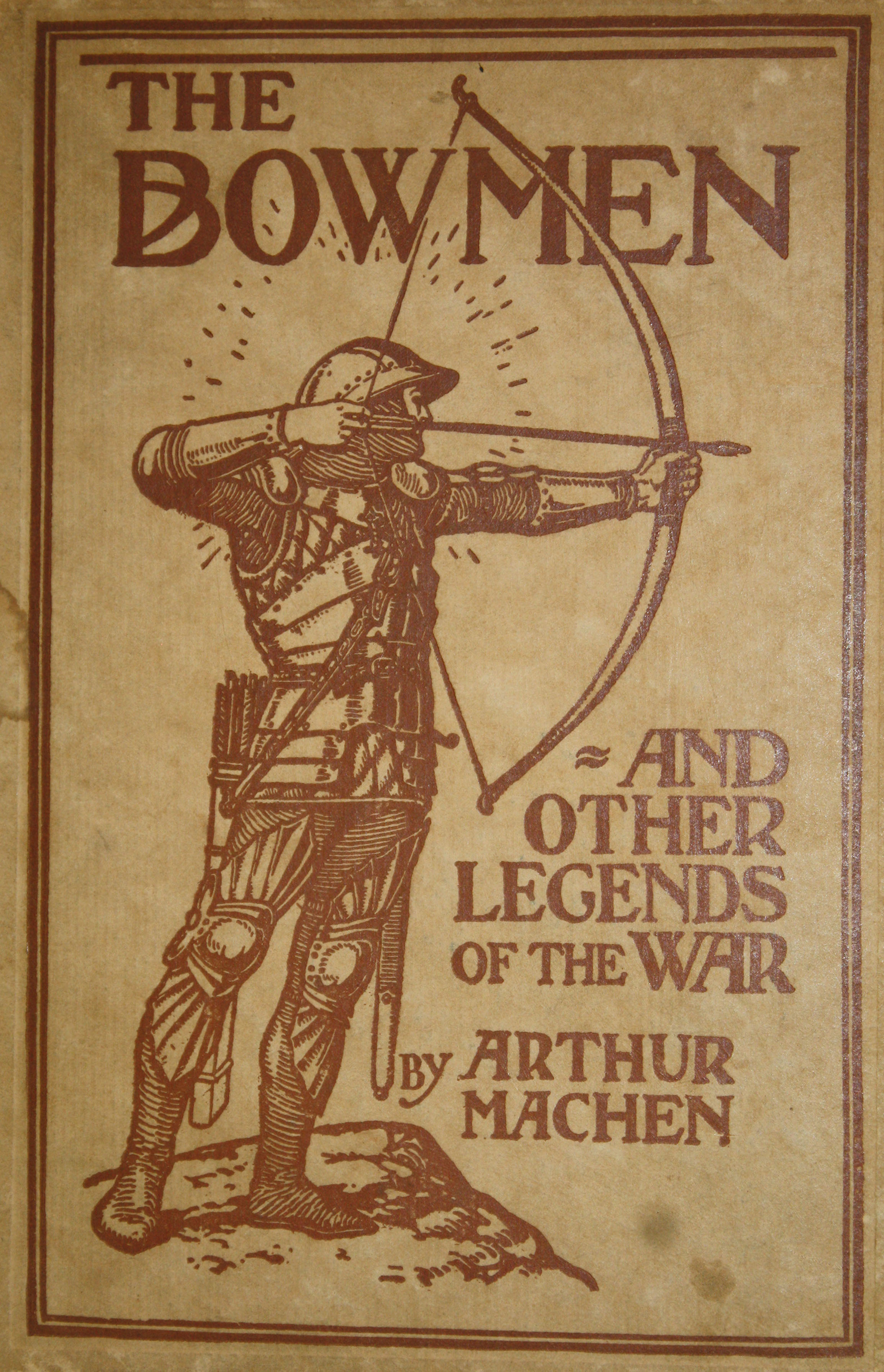

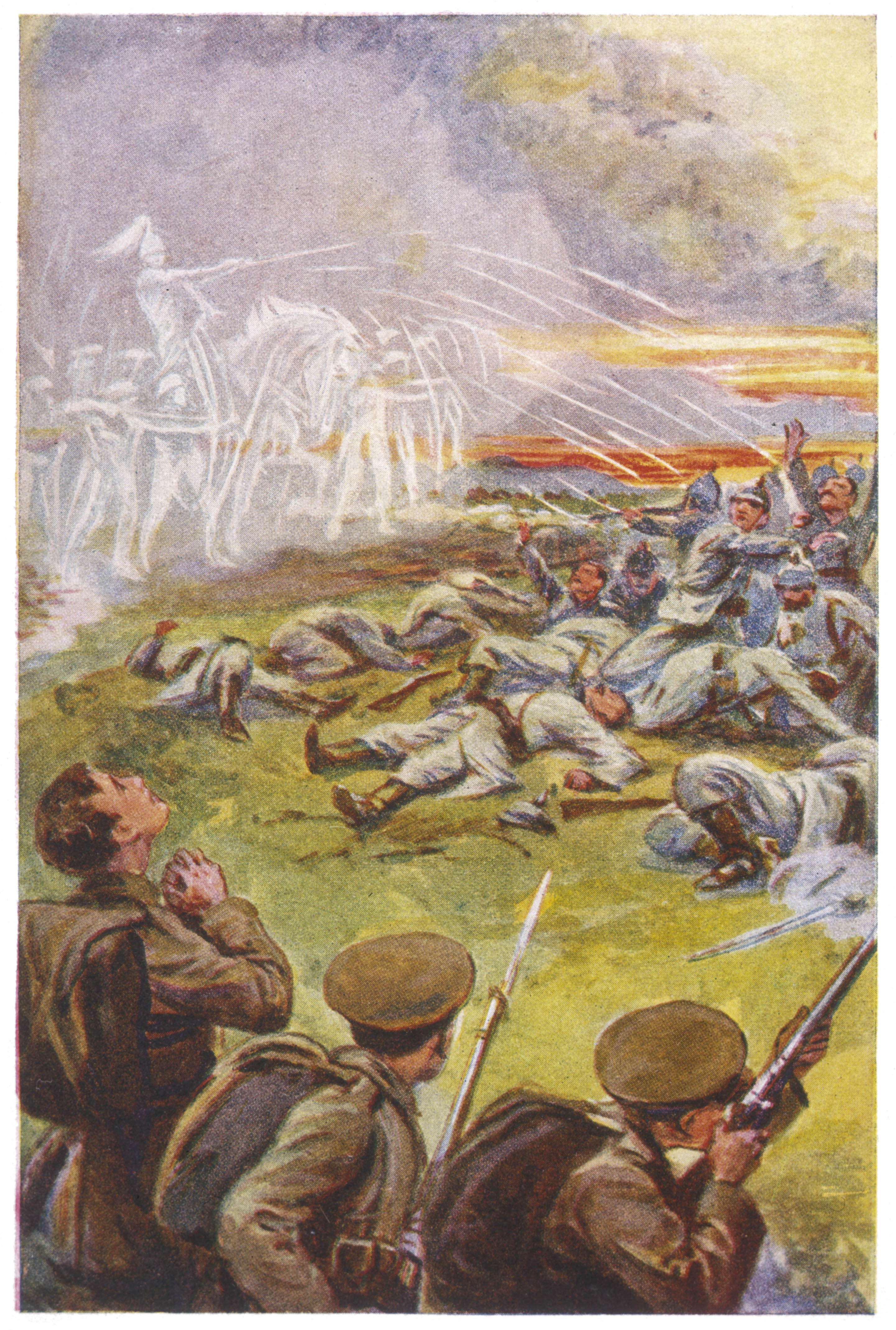

The psychic need of the British public for mythic inspiration and identification is shown by the birth of the legend of the “Angels of Mons” from a fictional newspaper account of the appearance of English bowmen from the battle of Agincourt appearing at the August 1914 battle of Mons to strike down the advancing German hordes.

The British public chose to believe this was true, even though the author took the pains to publish a book explaining that it was a work of fiction. [48]

The Bowmen of Mons come to the aid of the British and cause havoc among their enemies. Image courtesy of the Mary Evans Picture Library (no. 10024251).

Massive propaganda efforts were made by the belligerent powers to encourage their citizenry to stay in the fight while the slaughter continued month after month. The fighting in the trenches along the Western Front was almost indescribable and truthful descriptions of its horrors were actively suppressed. [49] It is self-evident that governmental efforts to keep the populace in the war were successful because none of the Western Allied powers (unlike Russia) were forced by popular revolt to withdraw from the fighting — although France came the closest to doing so after the Nivelle Offensive of 1917.

A problem was that the horrors encountered at the Front in World War I and the actions that soldiers were compelled to undertake for survival did not comport with the Christian ethic. Struggling to make older religious and literary traditions work in the new age, artists and poets of World War I often portrayed the soldier of World War I as a type of Christ who brought redemption through suffering and death. This portrayal was an obvious attempt to find meaning in the midst of almost apocalyptic destruction. [50] Those who survived the fighting remained haunted by it for their entire lives. [51]

The problem with the portrayal of the soldier as a “type of Christ” is that the experience of the trenches did not fit in with any traditional Christian framework.

The English soldier poet Wilfred Owen wrote of his internal conflict: “Christ is literally in no man’s land. There men often hear his voice. Greater love hath no man than this, that a man lay down his life — for a friend.” Owen found himself “more and more Christian as I walk the unchristian ways of Christendom” and told his mother:

This practice of selective ignorance is, as I have pointed out, one cause of the war. Christians have deliberately cut some of the main teachings of their code. [52]

For 14 hours yesterday I was at work — teaching Christ to lift his cross by numbers, and how to adjust his crown … With a piece of silver I buy him every day, and with maps I make him familiar with the topography of Golgotha. [53]

France was secular by official policy in 1914–1918, and the masses fighting at the Front, along with their families back home, were left to struggle to find a mythic consolatory framework sufficient to bear the weight of hundreds of thousands of dead. In secular France, some Catholics persisted in a strong commitment to traditional Christian beliefs, which required tortured logic to support the fighting in the trenches and to find meaning in wounds and death there. A young Catholic seminarian serving in an infantry unit, later killed in action in 1918, expressed this sort of sentiment in a January 1, 1915, letter, characterizing his wounds as a joyful sacrifice for the rechristianization of France.

Derville wrote in a letter dated January 1, 1915:

I have been wounded twice within fifteen days, and the shock was so violent and the part of my body struck so crucial, that both times I believed I was only a few moments from death. And, you see, I keep an ineffaceable memory of these moments. In full conscience, I have made the sacrifice of my life, with joy, for the rechristianization of our country, for the greater love of God on the part of my parents and my friends, and I do not feel the least bitterness. This sacrifice will be even more easy and joyful now, because I have reflected a great deal on it since then. [54]

However, into the secular void of France came not rechristianization but a legend that outdid the Bowmen of Mons: The story of “Debout, les Morts!” (“Stand up, you Dead!”) was originally published as fact by right-wing politician and journalist Maurice Barrès who claimed simply to be recounting the story of an April 18, 1915, battle told by a participant, Lt. Jacques Péricard. According to Péricard, Barrès, when the Germans were about to overrun his position, Péricard shouted, “Debout, les Morts!” to the corpses of dead French soldiers around him who rose to their feet in a scene reminiscent of that in the Valley of Dry Bones in the Book of Ezekiel, took up the machine guns, grenades and other weapons lying about and drove back the Germans. These were not apparitions from the sky but resurrected individual soldiers, supposedly known personally by Lt. Péricard. [55]

A French departure trench just before zero hour. Image Credit:Library of Congress, Prints & Photographs Division, Stereograph Cards, LC-USZ62-93510.

Maurice Barrès became so committed to the story of “Debout les Morts” that he proposed that dead soldiers be allowed to vote, a suffrage des morts, in which widows could vote in place of their deceased husbands. This proposition was not accepted. Leonard V. Smith notes that, “Political opinion in a country that did not permit women to vote until 1944 did not welcome the prospect of women casting ballots, on behalf of their deceased husbands or otherwise.” [56]

Nowhere was propaganda used to greater effect to mobilize the citizenry during World War I than in the United States of America. President Woodrow Wilson had a major problem with consistency on his hands when the United States declared war on Germany in April 1917 because he had run for President in the fall of 1916 on a peace platform of keeping America out of the war in Europe. Wilson turned immediately to one of his chief strategists from the 1916 campaign, George Creel, crusading editor of Denver’s Rocky Mountain News. Creel almost overnight created the so-called Creel Committee (officially named the Committee for Public Information) to propagandize the war effort and described the challenge he faced as follows (with the commentary of Allen Axelrod):

“While America’s summons was answered without question by the citizenship as a whole,” Creel wrote after the war, ‘“it is to be remembered that during the three and a half years of our neutrality the land had been torn by a thousand divisive prejudices, stunned by the voices of anger and confusion, and muddled by the pull and haul of opposed interests.” Torn, stunned, muddled . Such are all too often the adjectives associated with a democratic people, a people free to think for themselves rather than simply obey a king or dictator. Creel continued: “These were conditions that could not be permitted to endure. What we had to have was no mere surface unity, but a passionate belief in the justice of America’s cause that should weld the people of the United States into one white-hot mass instinct with fraternity, devotion, courage, and deathless determination.” One white-hot mass . Was this a concept and a state of being compatible with democracy? It was a question Creel clearly asked himself. Then he offered an answer: “The war-will , the will-to-win, of a democracy depends upon the degree to which each one of all the people of that democracy can concentrate and consecrate body and soul and spirit in the supreme effort of service and sacrifice. What had to be driven home was that all business was the nation’s business, and every task a common task for a single purpose.’” [57]

Creel seems to have been given almost plenary powers by President Wilson and totally overshadowed the other two members of his Committee, who happened to be the Secretaries of the Army and Navy. Although subject to harsh criticism from members of Congress such as North Carolina’s Representative Claude Kitchin, Creel successfully organized one of the most significant and massive propaganda efforts in history, enlisting top artists, filmmakers, and others to devote their efforts to propagandizing the War. Among his most significant innovations were the “Four Minute Men,” teams of local citizens who gave four minute speeches in movie houses supporting the war effort. Modern propaganda of the scope and scale we know today was created by George Creel to support the American effort in World War I, and it has been often noted how the all encompassing propaganda efforts to create and control public opinion were ironically at odds with the notion that this was the war to make the world “safe for democracy.” It is clear that Hitler and his minister of propaganda Josef Goebbels greatly admired and copied George Creel’s Committee for Public Information. [58]

The art of the poster had reached its height in the years before 1914, and the talent of the top poster artists was put to use by all the major combatants, including the United States through the Creel Commission to produce a stunning art as propaganda for recruiting for the sale of war bonds, to encourage home war gardens, to urge support for the YMCA, to raise money for the Red Cross and other Allied causes. [59]

Image Credits: Library of Congress, Prints & Photographs Division, WWI Posters, LC-USZC4-621 and LC-USZC4-1281.

There are many poster images of heroic soldiers and Marines charging into battle and the phrase Pro Patria is used without irony. [60]

Image Credits: Library of Congress, Prints & Photographs Division, WWI Posters, LC-USZC4-7566 and LC-USZC4-1539.

Allied posters depict Germans as brutish Huns, hands and bayonets dripping with blood or as a “Mad Brute” of a gigantic snarling King Kong-like ape wearing a helmet labeled “Militarism,” carrying a club labeled “Kultur,” and clutching in its arms a woman from whose breasts her gown has slipped. [61]

Image Credit: Library of Congress, Prints & Photographs Division, WWI Posters, LC-USZC4-2950.

Boy Scouts handed a sword inscribed “Be Prepared” to Lady Liberty who was usually portrayed as a Gibson Girl in a flowing gown that graced her figure to full effect. [62]

Image Credit: Library of Congress, Prints & Photographs Division, WWI Posters, LC-USZC4-1127.

Even women on the home front were encouraged to save their country by buying war savings stamps just as Joan of Arc saved France. [63]

Image Credit: Library of Congress, Prints & Photographs Division, WWI Posters, LC-USZC4-9551.

The American counter-narrative began during World War I with massive draft resistance, particularly in the South where former Populist Party leader turned white supremacist Tom Watson of Georgia stirred up anti-draft sentiment with his newspaper, the Jeffersonian. [64] The federal government struck back against those who would preach resistance to conscription with the Espionage Act, one of the greatest violations of civil liberties in American history. Socialist leader Eugene Debs was convicted and imprisoned under the Espionage Act for giving a speech in Canton, Ohio, in July 1918 that questioned the America’s war effort but did not even mention conscription:

[T]he working class who fight the battles, the working class who make the sacrifices, the working class who shed the blood, the working class who furnish the corpses, the working class has never yet had a voice in declaring war. [65]

Eugene V. Debs’ conviction was upheld in a unanimous opinion of the U.S. Supreme Court written by none other than Justice Oliver Wendell Holmes, Jr. [66]

Despite the federal government’s efforts, there was massive draft resistance in the United States during World War I, with desertion rates of 11.8% in Massachusetts, 12.7% in California, and 13.1% in New York. The lowest desertion rate in the country was Iowa’s 4.4% and in the South North Carolina’s 7%, but it was 12.2% in Mississippi, 13.5% in Alabama and 20.4% in Florida. More than 60% of all deserters in the South were black. Clearly, the patriotic narrative promulgated by the Creel Commission failed to persuade many people. In 1920 in Georgia, Tom Watson won a seat in the U.S. Senate by defeating the sitting Governor and U.S. Senator in a campaign in which he criticized Wilson’s conduct of the war, attacked the American Legion, and opposed U.S. entry into the League of Nations. [67]

Nonetheless, mythic glorification has staying power. And that staying power of the mythologization of war manifests itself especially in the commemoration of war dead. [68] World War I’s most famous poem, “In Flanders Fields” was written in 1915 by Canadian physician John McCrae. Far from expressing anti-war sentiment, “In Flanders Fields” portrays the dead urging the reader to “[t]ake up our quarrel with the foe.” The red poppy became the preeminent symbol of the war dead. In Canada after World War I, the war dead were spoken of as having risen from the dead in a resurrection that is depicted in the National War Memorial in Ottawa in which statutes of a group of soldiers walk through an Arch in a scene representing the resurrection from death to life. [69]

National War Memorial, Ottawa, Canada, (sculpted and built, 1926-1938, dedicated 1939), designed by Vernon March. Photo by Jcart1534, published under a creative commons license (CC-BY-SA-3.0), and made available via Wikimedia Commons.

“Dulce et decorum est” might have been discredited by Wilfred Owen, but it was inscribed on a host of World War I Canadian memorials and often appeared in the unveiling program along with another staple, Pericles’ Funeral Oration. [70]

At the end of World War I, film director Abel Gance, with the help of amputee veteran of the trenches and avant garde poet Blaise Cendrars, translated the concept of the redemptive return of the dead from the battlefield to their home village in the film “ J’accuse ” which concludes with the ghosts of dead soldiers returning to home to cry “ J’accuse! ” at the villagers, reminding them “of their venality and weakness, and meant to shock them into a decent life, worthy of the men bleeding for them.” [71]

In post-World War I Germany, painters worked with the theme of redemption through suffering and resurrection of soldiers. However, “Der Krieg,” the 1929/31 triptych with predella by Otto Dix provides little comfort with its realistic portrayal of ghastly horrors of the trenches in the triptych and the corpse of a soldier stretched out horizontally in the predella in the chilling manner of Hans Holbein the Younger’s “Der Leichnam Christi im Grabe” (1521). [72]

A feeling of hopelessness is the result.

The horrors of the trenches ultimately led some to question and debunk the romanticization of military violence. [73] Post-war memorial ceremonies for the dead came to be limited to the simple laying of a wreath at the Tomb of the Unknown or at the Cenotaph. Steven Trout has traced the see-saw battle for control of the memory of war represented by the Unknown Soldier buried at Arlington, Virginia, as poets, novelists and preachers increasingly through the 1920s and 1930s questioned whether the Tomb of the Unknown might be monument to militarism and even raised the possibility that the Unknown Soldier might be a black man in order to mock traditional patriotic sensibilities. [74] Perhaps the most famous work debunking all the glory and honor that the Tomb of the Unknown was supposed to represent was John Dos Passos’ poem, “The Body of an American,” the conclusion of Dos Passos’ novel, 1919. [75] It was published in 1932 as post-World War I anti-war sentiment was peaking. Calling the Unknown Soldier “John Doe,” the poem focuses the reader’s attention on the gruesome reality of war, while the term hundred per cent refers to being 100% American, an obviously nationalistic concept:

How did they pick John Doe? . . .

how can you tell a guy’s a hundredpercent when all you’ve got’s a gunnysack

full of bones, bronze buttons stamped with the screaming eagle and a pair of roll puttees?

… and the gagging chloride and the puky dirtstench of the yearold dead

busboy harveststiff hogcaller boyscout champeen cornshucker of Western Kansas bellhop at the United States Hotel at Saratoga Springs office boy callboy fruiter telephone lineman longshoreman lumberjack plumber’s helper,

worked for an exterminating company in Union City, filled pipes in an opium joint in Trenton, N.J.

Y.M.C.A. secretary, express agent, truckdriver, fordmechanic, sold books in Denver Colorado: Madam would you be willing to help a young man work his way through college?

The shell had his number on it.

* * * * *

The blood ran into the ground

. . .

The identification tag was in the bottom of the Marne.

The blood ran into the ground, the brains oozed out of the cracked skull and were licked up by the trenchrats, the belly swelled and raised a generation of blue-bottle flies.

how can you tell a guy’s a hundredpercent when all you’ve got’s a gunnysack

full of bones, bronze buttons stamped with the screaming eagle and a pair of roll puttees?

… and the gagging chloride and the puky dirtstench of the yearold dead

busboy harveststiff hogcaller boyscout champeen cornshucker of Western Kansas bellhop at the United States Hotel at Saratoga Springs office boy callboy fruiter telephone lineman longshoreman lumberjack plumber’s helper,

worked for an exterminating company in Union City, filled pipes in an opium joint in Trenton, N.J.

Y.M.C.A. secretary, express agent, truckdriver, fordmechanic, sold books in Denver Colorado: Madam would you be willing to help a young man work his way through college?

The shell had his number on it.

* * * * *

The blood ran into the ground

. . .

The identification tag was in the bottom of the Marne.

The blood ran into the ground, the brains oozed out of the cracked skull and were licked up by the trenchrats, the belly swelled and raised a generation of blue-bottle flies.

Remembering the war dead became a massive endeavor in the United States in the years after the First World War as it did after the American Civil War. The simple and unadorned biographies of Harvard’s Union dead in the Civil War, and its dead in the First World War are remarkable tributes. [76] After World War I, Harvard remembered its 373 war dead in Memorials of the Harvard Dead in the War against Germany with an article devoted to each of the dead written by a friend or family member. [77] My own copy of the Civil War Harvard Memorial Biographies is inscribed by William Dwight, a Union brigadier general, the book containing memorial biographies of two of his brothers, Lt. Col. Wilder Dwight, class of 1853, and Capt. Howard Dwight, class of 1857. Although the Harvard biographies are touchingly simple, they often make an ideological argument. The point is repeatedly made in Harvard’s World War I memorial volumes is that Harvard armed was Democracy armed. Pericles said, “Our constitution does not copy the laws of neighboring states; we are rather a pattern to others than imitators ourselves. Its administration favors the many instead of the few; this is why it is called a democracy.” (Thucydides 2.37)

Nothing illustrated this most cherished point than Harvard’s most prominent loss of all, the death in France on Bastille Day 1918 of the aviator Quentin Roosevelt ‘19, son of President Theodore Roosevelt and the sacrificial exemplar of America’s Age of Innocence. In a letter home from France, he mentioned that his books with him included Kenneth Grahame’s “The Wind in the Willows.” Quentin Roosevelt was killed in an aerial dogfight a few days after downing his first German airplane in combat. It was related after the war by a returning American POW, according to his memorial biography, that the death of Quentin Roosevelt, son of President Roosevelt, made a tremendous impression upon the German Army: “[I]t gave the soldiers a vision of the democracy of America.” [78] It would be easy for us to look back on these men who died in the War to End all Wars as hopelessly naïve. But it is important to grasp what they understood they were fighting for by contemplating writings such as the closing lines of the poem that Edgar Lee Masters wrote on the death of Paul Cody Bentley, Harvard class of 1917, the first member of the American Expeditionary Force to fall in France:

“And now I know why he rose so early/And hasted to school,/And hasted through life./ His eyes were fixed upon Democracy/And upon Immortality.”

Many copies of a statue named “The Spirit of the American Doughboy” by E. M. Viquesney were erected on courthouse squares and in other public places. [79] Oddly, for our purposes here, the Doughboy of the World War I memorial statue carried a rifle in horizontal position with his left hand and held a grenade in his raised right hand — neither in the exact pose of Harmodios’ sword raised for the “Harmodios blow” or the leveled sword of Aristogeiton, but close enough to make one think.

Ultimately, the memorialization of the American dead of World War I became a battlefield upon which the conflicting ideologies of national pride and anti-war revulsion fought. [80]

John Steuart Curry, The Return of Private Davis from the Argonne, 1928-1940. Image credit: Estate of John Steuart Curry and The Museum of Fine Arts, Houston; Museum purchase with funds provided by the Caroline Wiess Law Accessions Endowment Fund.

Fifty years later, in a similar conflict of ideologies, the lack of statues at the Vietnam Memorial in Washington, D.C., was controversial at the time, and the perceived gap was filled after some controversy by statues of three male soldiers, stopping to listen and look at the jungle around them, and a statue of a female soldier. However, standing in contrast are the stark black marble walls of the Vietnam Memorial in Washington, D.C., inscribed only with the names of the dead, without a single word of comfort or patriotic exhortation. The Vietnam Memorial with its long list of names of the war dead stands in sharp contrast to the stirring words of Pericles’ Funeral Oration and Lincoln’s Gettysburg Address in which the war dead being commemorated are completely anonymous. [81] This dark gash in American earth is perhaps the most democratic war monument of all. With no words of praise or blame, no reference to glory or honor, to victory or defeat, the Vietnam Memorial is an eloquent silent tribute to the Americans whose lives were cut short in the War. And yet each time I go there, I am forced to think back on those bodies I saw floating in the Mekong River in May 1970 and to reflect that hundreds of thousands of Vietnamese, Cambodians and Laotians who died in the war and have no memorial. And, on the other hand, I am also forced to consider whether this reflective Memorial Wall will be sufficient inspiration for champions of democracy to take up the fight to defend it, when the need comes, as surely it must, if history be any guide. [82]

This little survey of poetry and propaganda of war and its memorials comes to a conclusion without any mention of the significant war poetry of World War II. That awaits review on another day. Suffice it to say that, like Wilfred Owen and Isaac Rosenberg, many of the best British poets of the Second World War such as Keith Douglas (1920–1944), Alun Lewis (1915–1944) and Sidney Keyes (1922–1943) perished in the War. The simple and direct violence of Keith Douglas’ “How to Kill,” written in North Africa in 1943 expresses a literary ethic shorn of attempts to revive older traditions.

In World War I poetry, soldiers die, being sacrificed as a type of Christ, which gives redemptive meaning to their deaths. In World War II poetry, this is no longer true. War is death and violence without redemptive purpose, resulting in horrible deaths like that of Randall Jarrell’s ball turret gunner who is poured out of the ball turret a dead wet mess — born again dead, as it were, in a new and terrible age — and the death of the German or Italian at the other end of Keith Douglas’s rifle shot in “How to Kill,” written by a soldier who must have known his own death might be so described by an enemy shooter.

No longer can we find a Wilfred Owen “with his decadent aestheticism and Evangelical upbringing” looking back to “the strength and sweetness of the Romantic-Decadent lyric tradition, being brought to bear witness to the horrors of industrial modernity and pouring forth as an aria for the death of the European bourgeois consciousness” [83] nor an Isaac Rosenberg who “reaches beyond Romanticism to the Metaphysical Poets and tries to forge a radical modernist aesthetic” [84] in which he inverts the elegiac tradition of pastoral poetry into a terrifying soliloquy on a trench rat in “Break of Day in the Trenches” which Paul Fussell calls “in my view, the greatest poem of the War.” [85] In America, Randall Jarrell (1914—1965), who wrote “The Death of the Ball Turret Gunner,” stepped in front of a car in Chapel Hill in 1965 during my sophomore year there. It was left to Cecil Day-Lewis to speak the truth in his poem “Where Are the War Poets?”:

They who in folly or mere greed

Enslaved religion, markets, laws,

Borrow our language now and bid

Us to speak up in freedom’s cause.

Enslaved religion, markets, laws,

Borrow our language now and bid

Us to speak up in freedom’s cause.

It is the logic of our times,

No subject for immortal verse —

That we who lived by honest dreams

Defend the bad against the worse. [86]

By the time of the Vietnam War, 50 years of warfare produced scorching anti-war poetry that reserved the elegiac tradition to describe the supposed enemy and not friends, such as Philip Appleman’s poem, “Waiting for the Fire.” [87]

Pericles: What does all this mythmaking and propagandizing have to teach us about the Tyrant Slayers, Pericles and Athens during the Pentecontaetia?

There are stunning parallels between Athens’ situation after the Persian Wars and America’s own situation after WW II: [88]

- Each took a leading role in a coalition of allies that defeated a mortal threat, Persia in the case of Athens and Germany and Japan in that of the USA.

- Athens led in forming the Delian League while the U.S.A. led in forming the United Nations.

- For Athens, alliance turned into hegemony, but for the U.S.A., alliance evolved into the Pax Americana with American troops stationed throughout the world and large subsidies being paid to many foreign nations.

- The Delian League treasury became an Athenian war chest which was replenished thereafter by payments of tribute by the states of the Athenian Empire, but the American taxpayer became a major funder of the United Nations and many foreign military forces.

- Proxy wars were fought by both Athens and America and both were major naval powers.

- Pericles reacted to the forces arrayed against the Athenian democratic polis by taking steps that seem eerily similar to those measures pushed not by liberals but by conservatives in present day American politics.

- Curtailment of the citizenship. [89]

- Physical isolation of Athens as if it were an island with the building Long Walls from the City of Athens down to the port of the Piraeus.

- Abandonment of agriculture for finance and trade.

- Obsession with autochthony — see, the Cyzikene electrum staters with Athenian symbols such as Erichthonios, the cicada and Harmodios and Aristogeiton.

Edith Foster calls attention to Pericles’ almost impious rhetoric about Athens ruling the sea, .” . . in his effort to convince the Athenians to continue to fight the war, Pericles rejects Athens’ actual natural surroundings in Attica and employs the endless and symbolic elements of nature to create, in speech, a glorious, but impossible, even unreal, naval empire for Athens. Pericles is the poet of the empire, as he himself partly admits ( … 2.42.2) … and therefore ‘adorns things to make them seem greater’, just as Thucydides says poets will do (1.10.3, 1.21.1)” [90] A review of the history of ethnic cleansing and genocide over the past 500 years from the British in Ireland to the Nazi Holocaust to Cambodia and Rwanda reveals that repeatedly a precursor of ethnic cleansing and genocide has been mass persuasion utilizing certain persistent themes including “race, antiquity, agriculture and expansion.” [91]

The parallels of the blood-drenched recent past with the influence and control that Pericles exercised over the Athenian polis are chilling, even for one like myself who has been enthralled with the Golden Age of Athens since I was a small child and astounded by Athens’ many and varied intellectual, scientific, political, artistic and literary accomplishments of multi-millennial importance. I must conclude that the dekatos autos, as the Athenian mastermind in the last 20 years or so of the Penteconaetia, became more and more dominant by carrying out an effective propaganda campaign in order to motivate his fellow Athenians for the tasks of hegemony over an empire. And he was successful. The comic poets criticized Athenian leaders for imperial mismanagement but the evidence is insubstantial for their outright questioning of the justification for the Empire. [92]

And, yet … who cannot be dazzled by the loftiness of Pericles concepts, except those who were subjugated and had to pay the bills. In the Congress Decree and the Funeral Oration, we see an idealized vision of Athens, the School of Hellas, and indeed of the world that continues to inspire and enthrall. [93] But that does not mean that it should not be questioned. Nietzsche wrote that Pericles’ Funeral Oration was “like a transfiguring evening glow in whose light the evil day that preceded it could be forgotten.” [94] Hannah Arendt, perhaps surprisingly, took a tack similar to Nietzsche, in her view of the Funeral Oration:

The words of Pericles, as Thucydides reports them, are perhaps unique in their supreme confidence that men can enact and save their greatness at the same time and, as it were, by one and the same gesture. [95]

Arendt’s approach is perhaps explicable by an almost desperate search for that which was hopeful and good in human affairs following the Holocaust and her great admiration for the public space of the Greek polis.

Nearly 600 years after the Age of Pericles, during the reign of that Philhellenic lover of Athens, the Emperor Hadrian, the Orator Aelius Aristeides in Panathenaicus presented a vision of Athens, stripped of her political power, as the head of an empire, not political, but one of philanthropia and wisdom; in Nicole Loraux’s words:

[W]hereas the “true” empire, the humanist empire whose advent is lauded by Aelius Aristides, has always existed in potential, the military, political power which for the Athenians of the classical period constituted reality itself, is interpreted after the event as a stage in the educational process and becomes an epiphenomenon, at most a premonitory sign. [96]

What does the historical example of Pericles and Athens during the Pentecontaetia teach us about the present and future of America?

Effective use of propaganda by the leader of a democratic state might be viewed as simply the construction of a dike or levy to keep the stream of fortune within its banks, as recommended by Machiavelli in The Prince. However, propaganda, as Jacques Ellul so insightfully pointed out, turns into a totalitarian tool when it moves from opinion to myth making. Remember the key principle: A democracy is based on opinion, not belief. Once blind acceptance on faith of articles of a political creed is sold to the citizenry, as opposed to the responsibility of each citizen to develop his or her own opinion, democracy moves toward totalitarianism in the hands of those who dictate the beliefs.

Today in America, many are trying to sound the alarm, but vast tides of money pouring out propaganda over the airwaves are drowning out the alarms. Our mechanisms of propaganda are now under the control of the very rich after the U.S. Supreme Court’s decision in Citizens United v. Federal Election Commission, 558 U.S. 50, 130 S.Ct. 876 (2010). The parallels with ancient Athens are shockingly similar. The Oligarchs now control the airwaves, a situation that would have been very familiar to Greeks in the archaic period. Although they knew nothing about airwaves and electronic propaganda, they would have recognized what is happening to us.

All who claim to love democracy need to pause and remember this: Winning can be losing. The political philosopher Hanna Arendt elucidated this in her writings which touched on ancient Athens. For Arendt, the most important political passion is courage whose essence was the willingness of the political actor “to risk his life.” “[T]oo great a love for life obstructed freedom” and “was a sure sign of slavishness.” [97] Other requisites for the political actor, according to Arendt, are the pursuit of public happiness, the taste of public freedom, and an ambition for excellence regardless of status or even reward. Arendt did not include the will to power, “the passion to rule or govern” which, contra Nietzche and Weber, Arendt thought had no role in authentic politics because of the desire for control that it evinced. [98]

Unlike the classical scholar’s quest to get to the bottom of what actually may have happened in Antiquity, Arendt’s interest in the ancient Athenian democracy is “in equal parts aspiration, remembrance and recognition” with a “tempered romanticism” for the “thought fragments” that can be pried up from the past. [99] She seeks to use the Greeks as a provocation, “to press the past into the service of establishing the strangeness of the present” so that we may see what we have lost in terms of being political actors — for we no longer know the meaning of the outworn clichés that we use and no longer understand the full meaning of words like freedom and politics. [100] According to Arendt, we can regain that understanding when we regain access to the idealized Greek polis, and that is possible because the polis “is not the city-state in its physical location; it is the organization of the people as it arises out of acting and speaking together … no matter where they happen to be.” [101] Peter Euben characterizes Arendt’s totalitarian dystopia as “a world without politics”:

If we want a sense of what a world without politics … would be like we can look at Arendt’s portrait of totalitarianism. For her totalitarianism, which represents an extreme manifestation of developments present in modernity as a whole, fosters and responds to a radical loss of self, a cynical, bored indifference in the face of death or catastrophe, a penchant for historical abstractions as a guide to life, and a general contempt for the rules of common sense, along with a dogged adherence to traditions that have lost their point but not their hold. [102]

The purpose of winning in a democracy is to keep the democratic dialogue going at the center of the Classical Greek polis. And an all-out win that shuts down the dialogue with the losers insures ultimate defeat for the short-term winner. It is for this reason that Arendt comes face-to-face with the problem we have confronted here in the political and propaganda genius of Pericles. This is the problem of the hero in a democracy, of how to reconcile what Bernard Knox called “the heroic temper,” the “agonism” required for success in politics with the need for deliberation and fairness. How can the “associative, communal, democratic, deliberative Arendt” be “ ‘captured’ by the Greek model of greatness, heroism, agonism, and aethetisized politics”? [103] This is a question we have yet to fully answer — and yet Arendt provides the answer when she says that the most important political passion or virtue is courage and that the political actor who ventures out upon the public stage must be willing to risk his life to keep the political dialogue going. That is the true measure of a political hero.

I believe that Thucydides’ point of view about democracy is not that far from Arendt’s. The tyrannicide story was unpalatable to Thucydides because it enshrined reckless daring as an ideal — and that the reckless daring of heroes. It wasn’t given to Thucydides to understand the attraction of the emotional power of the “passionate enthusiasm” that Harmodios and Aristogeiton portrayed without which the Golden Age of Athens might never have occurred, but I believe that the example of the tyrant slayers had a powerful effect in classical Athens upon those who could and did understand the attraction of their example.