Sigurðsson, Gísli. 2004. The Medieval Icelandic Saga and Oral Tradition: A Discourse on Method. Trans. Nicholas Jones. Milman Parry Collection of Oral Literature 2. Cambridge, MA: Milman Parry Collection of Oral Literature. http://nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:hul.ebook:CHS_SigurdssonG.The_Medieval_Icelandic_Saga_and_Oral_Tradition.2004.

Introduction. Written Texts and Oral Traditions

The Medieval World View and the Individuality of Iceland

*

Oral Preservation, Latin Learning, and Snorri’s Edda

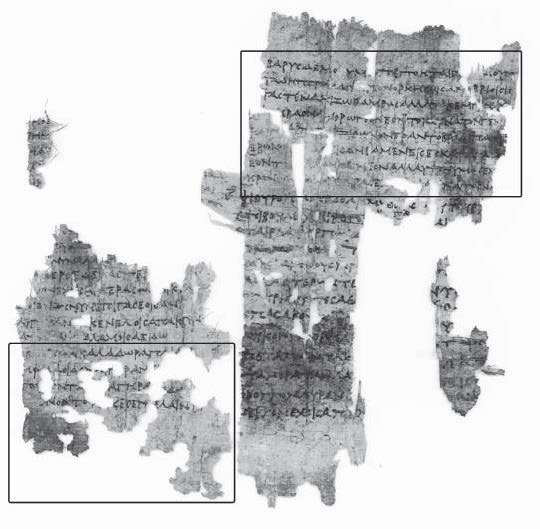

Figure 1: Sources of Snorri’s Skáldskaparmál, as per Faulkes 1993

One story in skaldic verse, on stone, and in Hymiskviða

- Ragnarsdrápa by Bragi gamli Boddason (‘Bragi the Old’)

- An otherwise unknown poem about Þórr by Ǫlvir

- An otherwise unknown poem about Þórr by Eysteinn

- An otherwise unknown poem about Þórr by Gamli gnævaðarskáld

- Húsdrápa by Úlfr Uggason.

*

Poetry and prose in Snorri’s Edda

*

The Origins of the Sagas: Two Types of Theory

Christianity and the Arrival of Literacy

The development of saga writing in Iceland in light of Latin literature

Three types of learned influence in the sagas

- Individual motifs and short episodes in the sagas derived directly from foreign writings.

- Ideological influences. Hermann Pálsson has propounded the view that various of the sagas of Icelanders can be seen as a kind of fable constructed around proverbs or well-known sayings, or as romans à clef based on real incidents from 13th-century history, and that they reflect more than anything the theological and philosophical preoccupations of that century.

- Various features of the narrative technique of the sagas; i.e. how their elements are put together to create integrated works using methods developed in historiographical writing in continental Europe in the 12th century.

| Landnámabók (S 283, H 244) | Hrafnkels saga (ÍF XI:97-8) |

| Hrafnkell hét maðr Hrafnsson; hann kom út síð landnámatíðar. Hann var enn fyrsta vetr í Breiðdal, en um várit fór hann upp um fjall. Hann áði í Skriðudal ok sofnaði; þá dreymði hann, at maðr kom at honum ok bað hann upp standa ok fara braut sem skjótast; hann vaknaði ok fór brutt. En er hann var skammt kominn, þá hljóp ofan fjallit allt, ok varð undir gǫltr ok griðungr, er hann átti. Síðan nam Hrafnkell Hrafnkelsdal ok bjó á Steinrøðarstǫðum. Hans son var Ásbjǫrn, faðir Helga, ok Þórir, faðir Hrafnkels goða, fǫður Sveinbjarnar. | Hallfreðr setti bú saman. […] En um várit fœrði Hallfreðr bú sitt norðr yfir heiði ok gerði bú þar, sem heitir í Geitdal. Ok eina nótt dreymði hann, at maðr kom at honum ok mælti: ‘Þar liggr þú, Hallfreðr, ok heldr óvarliga. Fœr þú á brott bú þitt ok vestr yfir Lagarfljót. Þar er heill þín ǫll.’ Eftir þat vaknar hann ok fœrir bú sitt út yfir Rangá í Tungu, þar sem síðan heitir á Hallfreðarstǫðum, ok bjó þar til elli. En honum varð þar eftir gǫltr ok hafr. Ok inn sama dag, sem Hallfreðr var í brott, hljóp skriða á húsin, ok týndusk þar þessir gripir, ok því heitir þat síðan í Geitdal.a |

- Traditional oral tales are equated with historical reliability.

- Pálsson attempts to show that the ‘author’ used written sources to obtain historical information for his story, but then goes on to say that the author used these sources with such lack of care that it is obvious he had no intention of writing history.

- Pálsson cites a number of what he considers serious historical ‘errors’ and anachronisms on the part of the ‘author’ of the saga, basing his knowledge of the ‘true’ facts on the very sources that the ‘author’ is supposed himself to have used when seeking information about the past.

*

Do Origins Matter for the Sagas as Literature?

Direct References to Oral Tradition—Evidence of What?

Impasse—And New Perspectives

The Comparative Approach

- That oral tradition necessarily maintains information accurately for centuries on end.

- That the oral can be equated with what might be historically true.

- That artistic expression precludes oral origins, and vice versa.

- That oral stories cannot survive for two or three hundred years among peoples and families living in a single location. This misconception has even led some scholars to assume that people in oral societies are incapable of having any genuine knowledge about their pasts (see Guðmundsson, H. 1997:42, 81, 296).

*

About This Research

- The role of the lawspeakers of the Icelandic Commonwealth and what we can find out about these men from the meager sources available, particularly as regards a) their attitudes to the writing of the laws, b) the party politics surrounding the election of the lawspeakers, and c) the growing role of the Church in 11th-, 12th-, and 13th-century Icelandic society.

- The range and scope of the oral poetic tradition in 13th-century Iceland as evidenced by the examples of verse quoted by Óláfr Þórðarson hvítaskáld in the Third Grammatical Treatise (Icelandic Þriðja málfrœðiritgerðin). By investigating where the poets he refers to came from and when they lived, we can build up a picture of the literary horizons of a man of the 13th century who was well versed in both the oral, secular learning of his family, the Sturlungar, and the Latin learning associated with the Church.

- Four characters that appear in more than one saga: the two father and son pairs Brodd-Helgi Þorgilsson and Víga-Bjarni, and Geitir Lýtingsson and Þorkell Geitisson. Here the focus is on whether and to what extent their characterizations match and/or conflict in the sources, and what this may signify.

- The genealogical information given about Helgi Ásbjarnarson and the Droplaugarson brothers in the different sagas. The questions addressed here concern the function of the genealogies and whether they can be supposed to derive from authorial ‘source work’ or whether there is anything to suggest that they are based on a general knowledge of genealogy shared by both the writers and their audiences.

- Accounts of the ‘same’ incidents in different sagas, viz. a) the battle of Bǫðvarsdalr, b) the story of how one of the Droplaugarson brothers’ ancestors obtained a wife abroad, c) the drowning of Helgi Ásbjarnarson’s first wife, d) the killing of Þorgrímr torðyfill, and e) the killing of Gunnarr Þiðrandabani. Tentative conclusions are drawn about the relationships between the different accounts and what they tell us about the genesis of the written sagas in light of their interplay with oral tradition.

Footnotes