Capra, Andrea. 2015. Plato's Four Muses: The Phaedrus and the Poetics of Philosophy. Hellenic Studies Series 67. Washington, DC: Center for Hellenic Studies. http://nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:hul.ebook:CHS_CapraA.Platos_Four_Muses.2014.

Chapter 1. Terpsichore

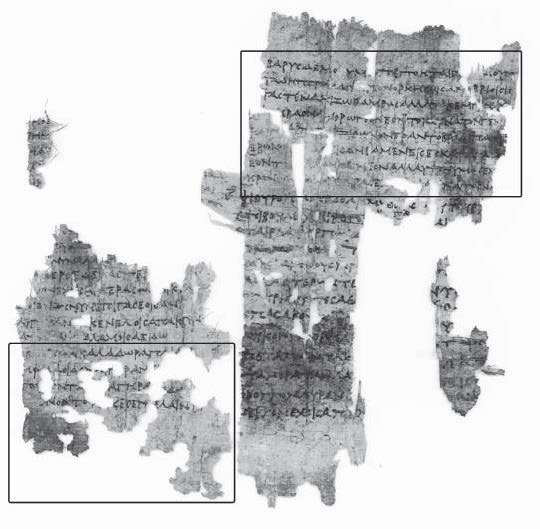

- On the third frieze of the François vase, the names of the Muses closely match Hesiod’s nine Muses in the Theogony, with one major exception: as is clear from the above image, one STÊSICHORÊ has “replaced” TERPSICHORÊ. This has prompted the suggestion that a Stesichorean performance might have influenced the depiction of the processing gods (see e.g. Stewart 1983 and, contra, Haslam 1991).

- Perhaps the very name STÊSICHOROS was itself a sprechender Name (“chorus setter”), the real name of the poet being TEISIAS. Such is the information provided by the lexicon Suda, s.v. “Stesichoros (IV p.433 Adler).”

- In the Phaedrus, Plato openly puns on Stesichorus’ name: his own speech is modeled after STESICHORUS of HIMERA son of EUPHÊMUS: Socrates will discuss HIMEROS (desire) in a respectful way (EUPHÊMÔS), and he will describe the celestial CHORUSES and of the gods and the blessed, celestial CHOREUTÊS (cf. 247a, 250b, 252d).

Socrates’ Palinode in the Phaedrus

Plato’s Stesichorus

ἀρχαῖον ἀείδειν, ὁ δὲ Γνήσιππος ἔστ’ ἀκούειν.

Stesichorus, and Alcman, and Simonides:

it is outmoded to sing them, we should go for Gnesippus.

Στησιχόρου πρὸς τὴν λύραν οἰνοχόην ἔκλεψεν.

And Socrates, receiving the song [14] from the right in relay

while singing Stesichorus to the lyre, stole the wine vessel.

The Divine Turn

- Sappho, Anacreon, and prose writers (Socrates’ bosom is “full” of them, 235c).

- Muses (Socrates summons the Μοῦσαι … λίγειαι to contribute to his μῦθος, 237a).

- Landscape (it makes Socrates νυμφόληπτος, 238d). [17]

- Nymphs (they “enthuse” Socrates ὑπὸ τῶν Νυμφῶν … ἐνθουσιάσω, 241d).

- Ibycus and Stesichorus (implicitly: Socrates follows their lead, 242d–243b).

- Muses (they arouse tender souls to a Bacchic frenzy, 245a).

- The cicadas (they can bestow upon humans the gift of the Muses, 258e–259d).

- Local gods and Muses’ prophets (i.e. the cicadas, inspiring Socrates, 262c–d).

- Pan and Nymphs (they are superior to Lysias, 263d; cf. 278b, Νυμφῶν νᾶμά τε καὶ μουσεῖον).

Socrates’ sources fall into two clear categories: [18] on the one hand, he is inspired by a number of local numina; on the other, by the Muses and certain poets—Socrates mentions Sappho, Anacreon, Ibycus and Stesichorus. It is important to note that two of these sources are mentioned before Socrates delivers his first, non-erotic speech (1, 2), one in a pause of speech shortly afterwards (3) two between the first and the second speech (4, 5), one within the second speech (6) and three after the end of both speeches (7, 8, 9). It would seem, therefore, that both speeches must be taken to be inspired, though the first, by extolling human prudence, is soon criticized as impious and non-divine. This is indeed a crucial problem, which I will discuss it in due course.

The Palinode: Socrates’ Re-Vision

Socrates’ Performance

Socrates vis-à-vis Stesichorus: Verse and Muses

Stesichorus’ request is striking, and it is no surprise that it was remembered: Aristophanes echoes it in the Peace (774–779), a sure indication that it was widely known to Athenian audiences.

just as wolves love the lamb, so is lovers’ affection for a boy

This hexameter line is irregular in that the word παῖδα breaks the rhythm in an unusual position (violation of Hermann’s bridge). [78] Interestingly, Socrates will later quote two lines allegedly taken from the repertoire of the Homeridae, one of which features precisely the same violation. [79] Somewhat paradoxically, then, the very irregularity of the hexameter has been construed as yet one more reason for preferring the indirect tradition to the non-hexametric text of the manuscripts, as if the crafting of slightly irregular hexameters were some kind of jocular “signature” on the part of Plato. [80]

- ὣς παῖδα φιλοῦσιν ἐρασταί (last words of Socrates’ first speech)

- Οὐκ ἔστ’ ἔτυμος λόγος οὗτος (PMG 192.1, i.e. line 1 of palinode)

- οὐδ’ ἵκεο Πέργαμα Τροίας (PMG 192.3, i.e. line 3 of palinode)

- Δεῦρ’ αὖτε θεὰ φιλόμολπε (PMG 193.9–10, i.e. incipit 1 of palinode)

- Χρυσόπτερε πάρθενε 〈Μοῖσα〉 [85] (PMG 193.11, i.e. incipit 2 of palinode)

These lines all share the same metrical pattern (which scans ‒‒⏑⏑‒⏑⏑‒x). To the ears of Plato’s original audiences, then, Socrates’ final words in the first speech announced the characteristic rhythm of the palinode, which is why Socrates calls them epê. Note also that the first line of the quotation (οὐκ ἔστ’ ἔτυμος λόγος οὗτος) is uttered a second time by Socrates, who introduces his second speech by punning on Stesichorus’ name (as we have seen) and by saying that “this is not a genuine logos, if it says that when a lover is there for the having one should rather grant favors to the man who is not” (244c). As such, this line stitches the two speeches together and is given a very special emphasis. Thus, a powerful Stesichorean network is at work here, insofar as the first speech ends on the very same “note” struck by the beginning of the second.

Stesichorus’ Shadow

The whole expression “he has an eidôlon as a counter-love for love” (εἴδωλον ἔρωτος ἀντέρωτα ἔχων) is rather obscure, and—what is more—the word “counter-love” (ἀντέρως) has no real parallel: all of its very few later instances depend on the Phaedrus. [89] Plato’s creation, I suggest, is best explained as a reworking of Stesichorus’ eidôlon, that is, of an image designed to provide a weird kind of ersatz love (note, also, the strange mention of the eye-disease, possibly one more reference to Stesichorus).

Conclusions

Endnote: New “Facts”

- A complete survey of the inspirational sources mentioned in the Phaedrus shows that Socrates is consistently portrayed as an inspired “poet” throughout the dialogue. The palinode is no exception.

- Among his “sources,” Socrates mentions four poets. According to biographical tradition, three of them, namely Anacreon, Ibycus, and Stesichorus, recovered after being involved in some kind of “incident,” and a similar story was probably circulated about Sappho. As is confirmed by later sources, the simultaneous mention of these poets is not coincidental, and there is evidence that Athens had incorporated the traditional biographies of some of them into the fabric of its own ideology.

- Scholars have long debated the number of poems Stesichorus devoted to Helen, given that the sources are random and contradictory. According to a recent interpretation, there was just one poem, which was delivered in the form of a theatrical performance divided into different parts (or acts) that later came to be known as distinct poems. This interpretation is consistent with a fresh and thorough reading of the Phaedrus:

- Points of vocabulary suggest that the invocation Socrates addresses to the Muses prior to his impious discourse is a Stesichorean pastiche.

- The final words of Socrates’ first speech are in the same meter as the first of Stesichorus’ palinode, as quoted by Socrates before he launches into his second (pious) speech (as such, they may hint at an unknown Stesichorean fragment).

- As Marian Demos has suggested, Socrates’ removal of his veil before delivering his second discourse corresponds to Stesichorus’ regaining of his sight in the performance of his Helen poem. At some point, Socrates even pretends to be blind and “makes expiation,” which may have been the cue for the singers to start their song. Taken together, these facts suggest that Socrates is reenacting Stesichorus’ performance.

- The whole conversation between Socrates and Phaedrus is actuated by the latter’s questioning of the myth of Boreas and Oreithyia: is the “mythostory” (mythologêma) true? Mythologêma is an intellectual catchword used specifically in a context where a rationalization of myth is attempted. At the same time, it prepares us for Stesichorus’ palinode, which is famously introduced by the words: “This story is not true.”

Footnotes