To commemorate the International Greek Language Day on February 9, Harvard University’s Center for Hellenic Studies and Dumbarton Oaks, and the Library of Congress have joined together to offer a brief historical glimpse into the language from antiquity to the present, and a presentation of Greek language highlights from the collections of the three institutions.

Ancient Greek and its Legacy

By Rebecka Lindau, Chief Librarian, Center for Hellenic Studies

All Americans know some ancient Greek as more than 5 percent of English words derive directly from the Greek language, timely words such as democracy, tyranny, plutocracy, oligarchy, autocrat, narcissist, and pandemic; many more words come to us from Greek via Latin and other Indo-European languages. Americans know the Greek alphabet through the “Greek” college system of fraternities and sororities and the first and last letters of the Greek alphabet, “the alpha and the omega” of something, and, of course, the mathematical value π. The Greek alphabet with its vowels, a Greek addition to the Phoenician alphabet, was the impetus for the Latin alphabet, i.e., our own, and that of many modern languages. A frustration for many beginning students of ancient Greek is its diacritics. Third century BCE librarian and scholar Aristophanes of Byzantium is credited with their introduction although they did not become formalized until late antiquity (see Nevila Pahumi’s contribution from LC below regarding the language debate in nineteenth and twentieth century Greece). Other language contributions of the ancient Greeks involved creating a writing system that was independent of religion and power, thus contributing to literacy beyond royal scribes and priests and priestesses.

Included in an exhibition at the library of Harvard’s Center for Hellenic Studies in Washington, DC are several examples of Greek writing on pottery, so called ostraca from which our term “ostracize” derives. A feature of Athenian democracy was to write the names of “undesirable” individuals, resulting in exile if the same name appeared on multiple pottery sherds.

Our earliest known example of ancient Greek appears around 1450-1200 BCE in a script referred to as Linear B, which was the writing system of the Mycenaeans, a people living in the Peloponnese ca. 1700-1100 BCE. They used clay tablets and other materials to document offerings to the gods, inventories of goods, and other regular business, governmental, and religious activities. The name Linear refers to the writing on horizontal lines and the B follows the writing system of the earlier Minoan civilization on Crete referred to as Linear A, which to this day has not been deciphered, but Linear A does not appear to be Greek.

The earliest literary work in Greek, and the introduction to the Greek language for countless students over several centuries in the western world, was the Iliad attributed to a man by the name of Homer, although as Harvard professors Milman Parry in the 1920s and Albert Lord in the 1960s (a third edition of his book The Singer of Tales was published in the CHS series in 2019) and, more recently, Gregory Nagy have demonstrated, the epic poem is based on oral tradition, so rather than viewing Homer (whose historicity has also been called into question) as a poet or “fiction” writer of stories about a war between Greeks and Trojans, the bard or rhapsodist (possibly several) may have been more a compiler or organizer of these stories, transmitted from generation to generation, also apparent in the poem’s mixing of Ionic and several other Greek dialects (for more on “The Homeric Question,” see G. S. Kirk, The Songs of Homer, Cambridge 1962, E. Havelock, Preface to Plato, Harvard 1963, C. Tsagalis, The Oral Palimpsest: Exploring Intertextuality in the Homeric Epics in the CHS series in 2008, M.L. West, The Making of the Iliad, OUP 2011). A second epic, also attributed to Homer, was the Odyssey about the Greek warrior’s long journey from the Trojan War to his home on the island of Ithaca, represented most recently in the film “The Return” with Ralph Fiennes as Odysseus and Juliette Binoche as his wife, Penelope.

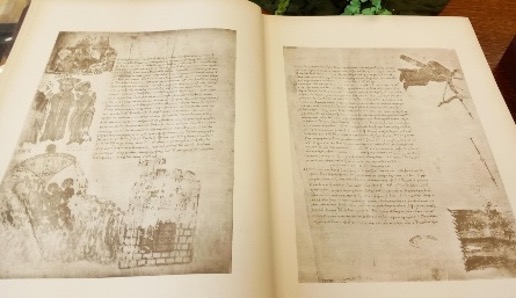

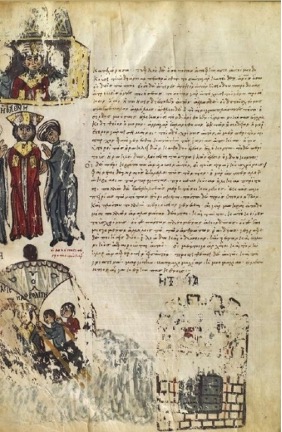

The exhibition in the library of CHS features a facsimile in its collection of a famous medieval manuscript of the Iliad referred to as “Venetus A.”

The original manuscript is illustrated in color. This left verso of the manuscript depicts the three goddesses Hera, Aphrodite, and Athena, and the so-called beauty contest or the Judgment of Paris, a catalyst for the events of the epos, at the beginning of book I.

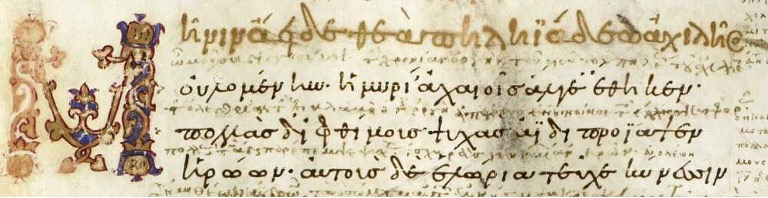

Μῆνιν ἄειδε, θεά, Πηληιάδεω Ἀχιλῆος οὐλομένην, ἣ μυρί᾿ Ἀχαιοῖς ἄλγε᾿ ἔθηκε… (Sing, goddess, about the rage of Peleus’ son Achilles, the fatal rage which brought countless sorrows upon the Greeks…). Thus begins the first book of the Iliad. The clay tablet featured in the exhibition is a modern rendering (originally, an April Fools’ joke) in Linear B by a former CHS residential fellow, Michele Bianconi, of this beginning of the first book of the Iliad.

“The Homeric Question,” in the modern era, originated with F. A. Wolfe’s Prolegomena ad Homerum from 1795, owned by the CHS and included in the exhibition, in which Wolfe argued that the Iliad and the Odyssey were originally two different poems by different authors gathered under the name of Homer whether by the poet or others. In the 1800s, G. Hermann (1831) argued that the poems were united but that they were expanded and modified later. A. Kirchhoff (1859) thought that the Odyssey was a compilation of three different poems. Both 19th century works are featured in the exhibition.

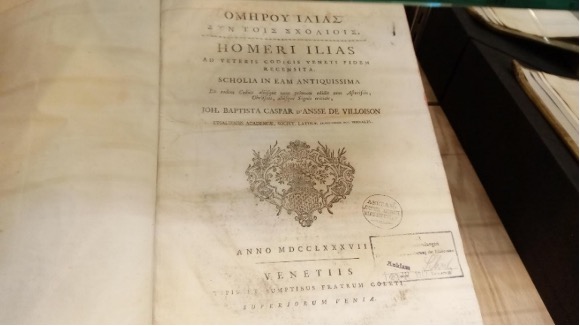

Also exhibited is Homer’s Iliad with ancient scholia and marginal notes by Johannes Baptista Caspar d’Ansse de Villoison, published in Venice, 1788, indicating supposititious, corrupt and transposed verses. Villoison who was professor of both ancient and modern Greek at Collège de France in Paris created a world sensation when this work was published as his reading was based on a, by this time, largely forgotten manuscript he had just rediscovered, Venetus A.

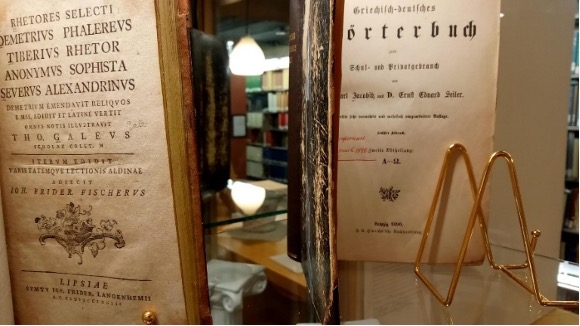

Also included in the exhibition is a book from the 18th century of works by rhetoricians and grammarians of the Greek language, Demetrius of Phaleron, Tiberius Rhetor, Alexandrinus Severus, and anonymous Sophists. The latter which have given us the rather pejorative term “sophistry” were itinerant teachers who specialized in various subjects to educate people though some viewed them as Besserwissers who sought to win arguments by using rhetorical devices in the Greek language.

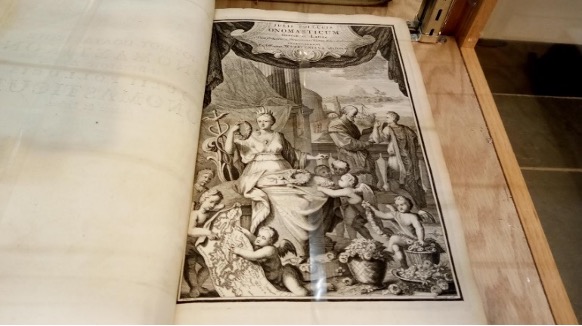

Also featured is Julius Pollux’ Onomastikon in 10 books, edited by Wolfgang Seber with a commentary by Gottfrid Jungermann, Amsterdam, 1706. Julius Pollux was a Greek grammarian and rhetorician in the 2nd century CE from Egypt, appointed to the chair of rhetoric in Athens by Roman Emperor Commodus. His thesaurus of Attic Greek was important for the learning and understanding of the Greek language during the Renaissance.

In addition to stone, papyrus, and pottery, Greek texts have been transmitted to us via parchment in the form of medieval and Renaissance manuscripts by monks, nuns, and religious and secular scholars. Besides the facsimile of Venetus A, the CHS library owns several other facsimiles of important manuscripts whose original language was Greek (κατὰ τὴν Ἑλλήνων γλῶσσαν). The following presents three newly acquired facsimiles.

Ilias Picta. The original manuscript (Codex F. 205 Inf.) is from the 5th century and is held in the Biblioteca Ambrosiana, Milan. Facsimile: Bern/Olten: Urs Graf, 1953. The Ambrosian Iliad contains mostly colored pasted fragment illustrations as the original manuscript illuminations were cut out, taking out much of the text. Some texts on the reverse of the pictures were pasted over with paper which was later removed, revealing the text underneath written in Greek uncials, a rounded letter script in all capital letters, popular from the 4th to the 8th centuries. The images in this manuscript are the only extant illustrations from antiquity that depict continuous scenes from the Iliad.

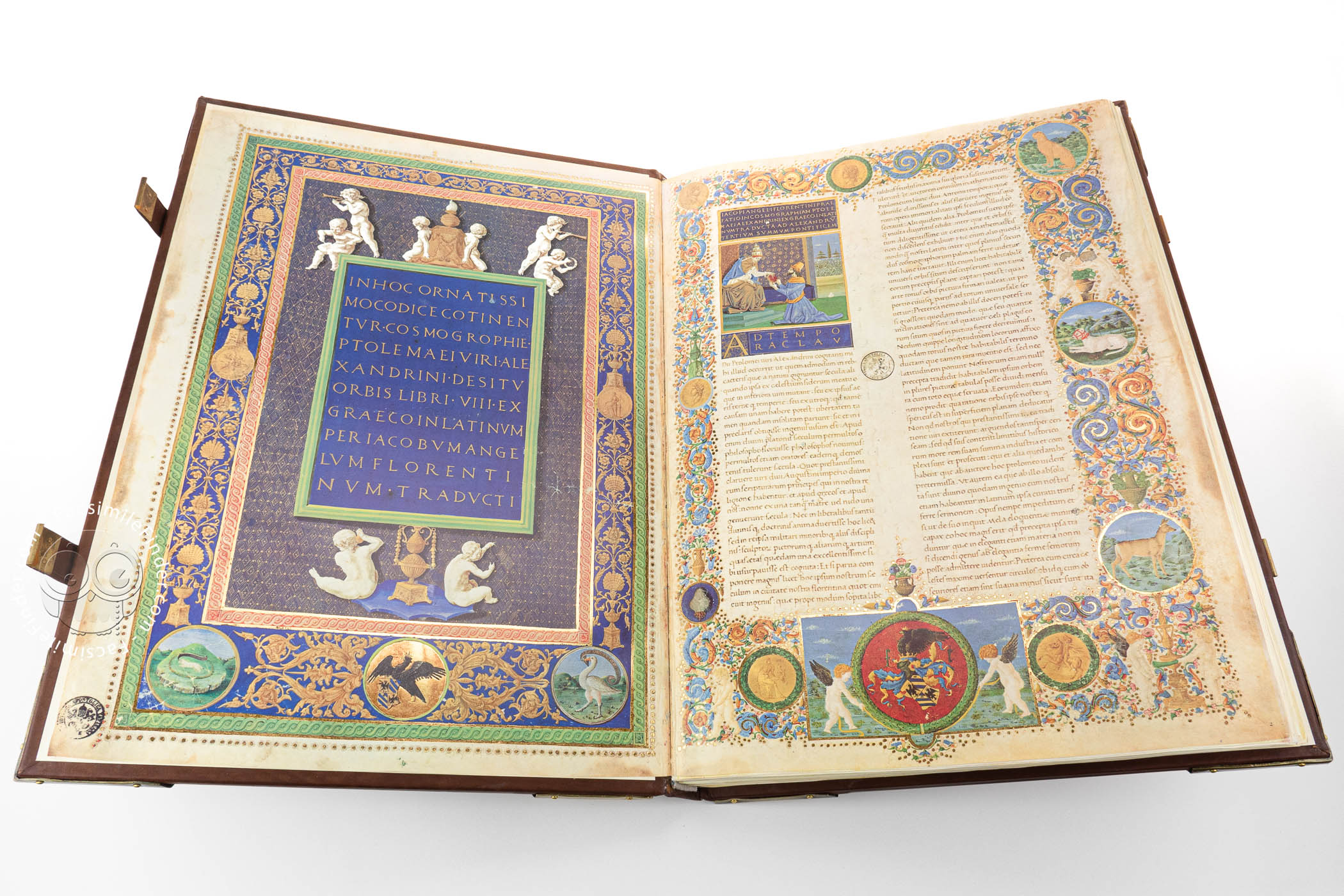

The first Latin translation from Greek of Ptolemy’s Geography or Cosmography was undertaken by the Florentine Jacobo d’Angelo (Jacobus Angelus) in 1409, published in this manuscript from 1472, illuminations by Francesco Rosselli, commissioned by Federico da Montefeltro, Duke of Urbino. The original (Codex Urb. Lat. 277) is in the Biblioteca Apostolica Vaticana. D’Angelo studied Greek under Manuel Chrysoloras in Venice (see Joshua Robinson’s Byzantine Greek section below). The codex contains maps of Europe, Asia, and Africa and a world map, as well as maps of major cities like Rome, Constantinople, Damascus, Alexandria, Venice, and Volterra (the rather modest town had lost a battle to Montefeltro). Although many of the maps were later additions, the world map is most likely by Πτολεμαῖος or Ptolemy himself, a famous Greek geographer, mathematician, and astronomer in the 2nd century CE, who based his map-making largely on mathematical and astronomical calculations detailed in the manuscript and the CHS facsimile. Facsimile: Zürich: Belser Verlag, 1983.

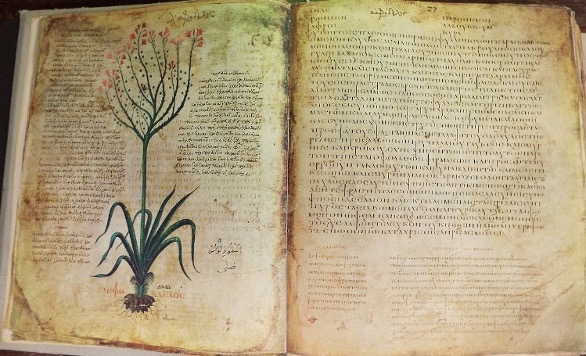

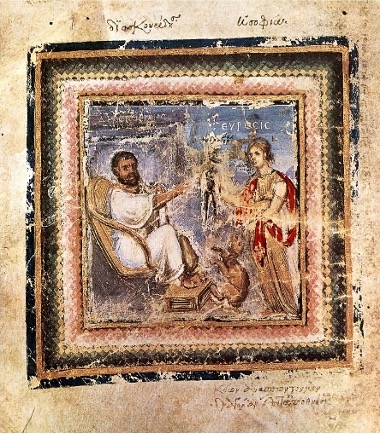

The original manuscript of the so called Vienna Dioscorides (Codex Vindobonensis med. Gr. 1) is dated to ca. 512 and is held in the Österreichische Nationalbibliothek, Vienna. It may seem to be better suited for Dumbarton Oaks to discuss as it is an early Byzantine manuscript, but the original Greek text and most images of plants and animals are from antiquity. The CHS library’s facsimile is of high quality and entirely in color and on parchment-looking paper from Graz: Akademische Druck- u. Verlagsanstalt, 1965-1970.

This work with the Greek title Περὶ ὕλης ἰατρικῆς or as it is commonly known in western Europe in Latin, De materia medica, about herbal or pharmaceutical materials, was written by a Πεδάνιος Διοσκουρίδης. We do not know much about Dioscorides. We know that he was born in the ancient city of Anazarbus, as he is referred to by contemporary sources as Dioscorides of Anazarbus, which was a town in Cilicia, Asia Minor, now more or less corresponding to Armenia near Cyprus and Syria some 2,000 years ago in the first century of the Common Era. He was probably a doctor in the Roman army under emperors Claudius and Nero, and as doctors were in those days, he would also have been a botanist and pharmacologist, or herbalist since ancient medicine was based largely on herbs.

The codex is a kind of encyclopedia, a pharmacopeia, in 5 volumes. In volume 1, for example, we learn about aromatic plants used in ointments — everyday products used for personal hygiene. A nutritious diet, exercise, and hygiene were all emphasized in ancient Greek medicine. We learn that shampoo was made from walnut, soap from elm, toothpaste from myrrh, etc. Other volumes catalog plants used more for what we generally think of as medicine, to treat illnesses, rather than preventing them, plants such as σίνηπι (sinepi), mustard, “suitable for hip diseases, and afflictions of the spleen. Treats baldness” and σῐ́κυς (sikus), cucumber, “eases the bowel; is appropriate to use for the bladder, and it revives those who faint if they should smell it.”

Producing this very large, thick and tall, and heavy manuscript would have entailed the killing of several hundred animals, usually sheep, goats, and calves to produce the almost 500 folios made of vellum or parchment, animal skin. A folio consists of 2 pages, recto and verso, front and back, so ca. 1,000 pages altogether. The manuscript contains ca. 400 extant, some are missing, full-page illustrations of medicinal plants describing in Greek (with later additions of plant names in Arabic, Hebrew, and several other languages) some 600 plants and many more herbal cures.

If you wish to learn more about these works or about ancient Greek and its legacy, or about the Center for Hellenic Studies and its library’s collections, exhibitions, and access policy, please consult the CHS website and follow its social media posts.

Celebrating Greek: New Acquisitions at Dumbarton Oaks

By Joshua Robinson, Byzantine Studies Librarian, Dumbarton Oaks

Dumbarton Oaks has recently made two notable acquisitions pertaining to the transmission of Greek learning in the Renaissance.

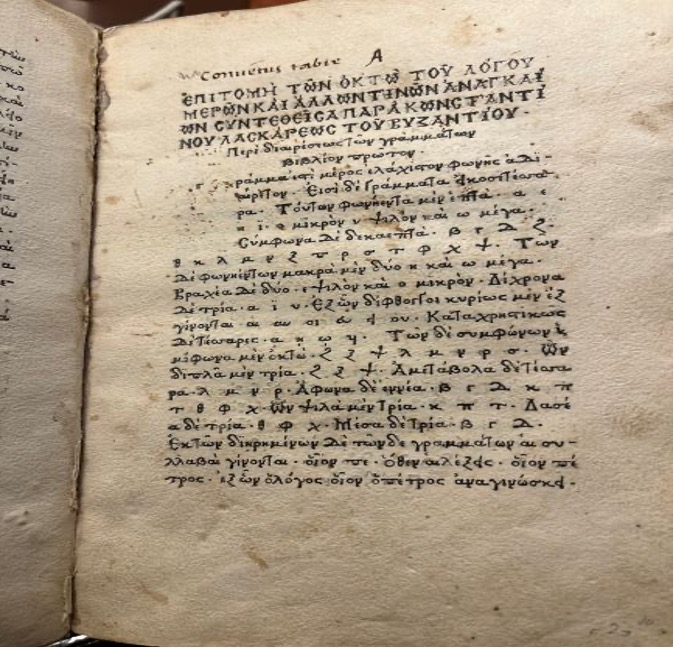

The first is a very early Venetian edition, from the Aldine press, of the Greek grammar in four books by Theodore of Gaza (1398-1475): Theodori Introductiuae grammatices libri quatuor…, Venice: Aldo Manuzio, 1495. It is bound with another work by Theodore, the De mensibus, as well as Apollonius Dyscolus’ De constructione and Ps-Herodianus’ De numeris. 12 x 8 inches, 198 leaves. Types in Greek and Latin.

This is the editio princeps of Theodore of Gaza’s Greek grammar, one of the first works of the Aldine press, and a cornerstone of Aldus’s printing program. The first five years of Aldus’s publishing program were dominated by important Greek books and crowned by the magnificent Aristotle. Many of the works printed by him in this period were designed to support its appreciation, including this respected grammar by Theodore.

Written in Greek for students of the ancient language, Theodore’s primer provides an immersive course of study in four books of increasing difficulty. One of his major innovations was the reduction of the then-standard thirteen verb conjugations to five. In his preface to the edition, Aldus praises Theodore’s “concinna … brevitate” (elegant brevity) and suggests that while it might be difficult on the first read, the second time will be only a delight.

Related holdings at Dumbarton Oaks

The second is a late-fifteenth century Greek manuscript of an abridged version of the Erotemata, an elementary Greek grammar composed by the Byzantine Greek classical scholar, humanist, philosopher, professor, and translator Manuel Chrysoloras (c.1350-1415).

The Erotemata, so-called because it was arranged according to the traditional ‘erotematic’ method of questions and answers, was the most influential and popular Greek grammatical textbook of the Italian Renaissance. It was the first basic Greek grammar in use in Western Europe, published in 1484 and widely reprinted, and enjoying considerable success not only among Chrysoloras’ pupils in Florence, but also among leading humanists: it was studied by Thomas Linacre at Oxford and by Erasmus at Cambridge.

The grammar has a very complex textual transmission, with the simultaneous circulation of the original ‘full’ version, and the more widespread and popular abridged text written between 1417-1418 by Chrysoloras’ pupil Guarino da Verona (1374-1460). The oldest extant copy of the full version is generally regarded to be Rome, BAV, Vat. Pal. Gr.116.

The manuscript acquired by Dumbarton Oaks is contemporaneous with the text’s first appearance in print in 1484. It is a decorated manuscript on paper in a contemporary Italian binding. 6.5 x 4.5 inches, comprising 31 folios, of 19 lines per page, bound in contemporary goatskin over thin wooden boards.

Related holdings at Dumbarton Oaks

Modern Greek and Collections

By Nevila Pahumi, Reference Librarian for Modern Greek, Library of Congress

Modern Greek (Νέα Ελληνικά) has been around since the Renaissance. It is derived from earlier forms of the same language, including both Byzantine and ancient Greek. The dividing line is traditionally thought to be the year 1453, coinciding with the Ottoman conquest of Constantinople, the capital city of the Byzantine Empire. Ottoman control of Byzantium, roughly cohering to the territory of the Eastern Roman Empire, happened in stages and was drawn out over several centuries.

After the Fall of Constantinople, Byzantine Greek went out of use. This prompted Greek scholars to find refuge in the West—in Italy, in particular. It was there that the Renaissance gave rise to the revival of classics, both Latin and ancient Greek. This trend persisted through the Enlightenment period, influencing the thinking of European elites, and in time, also the colonial and early republican-era American ones, too.

During the centuries of Ottoman rule, Greek dialects continued to be spoken throughout the mainland, the islands, and also in parts of Anatolia. This paved the way for the Demotic (Dimotikí), vernacular Greek that is, to emerge as one of the two dominant forms of modern Greek in the 1800s and 1900s. While the demotic was spoken widely, around the time of the Greek Revolution (1821), the intellectual and political elites maintained that Katharevousa (Καθαρεύουσα), a purer form of the language, was the one better suited for study and official purposes. Indeed, adherents of the two forms fought one another. One case involving the Church and the Queen led to widely publicized street riots in Athens in 1901 when a vernacular translation of the New Testament was published. After more than a century and a half of debate, demotic Greek was proclaimed the official language in 1976.

Estimates vary, but today modern Greek is spoken by some 13-25 million speakers worldwide. The majority live in Greece and in Cyprus. Other users (whether speakers, readers, or writers) of modern Greek comprise the global Greek diaspora. Greek is spoken by heritage communities which vary in size and age in Australia, Europe, North and South America, as well as in Turkey. The Greek communities of Australia and the United States are the largest ones outside of Greece proper.

The Library of Congress has been collecting materials on or about Greek since its beginnings as a parliamentary library in the early 1800s. In fact, books related to Greece like the now-digitized The Grecian history: from the original of Greece to the end of the Peloponnesian War, containing the space of about 1684: in two volumes came into the Library as part of the collection owned by Thomas Jefferson. Jefferson was a founding father of the American Republic as well as of the Library’s international collections. Language is perhaps the strongest component of the Library’s modern Greek collections, with about seventy percent of the material dating from 1821—the year of the Greek Independence. History is the second largest portion, logically one might say.

The Library’s modern Greek collections are scattered throughout the general and special collections. While much of the collections consist of print materials like books, the Library has also collected material in other genres including bound periodicals, maps, music scores, atlases, prints and photographs, manuscripts, motion pictures, and sound recordings. So that you get an idea of the age and range of Greek materials at the Library of Congress, we have featured some of our treasures below. They include excerpts from the very first Greek Renaissance manuscript, a playbill from the musical adaptation of the beloved 1964 film “Zorba”, and one of the twelve newly arrived Greek translations of the “The Dreamtime Duck of the Never Never” comic series by Don Rosa.

Americans growing up in the 1960s, 70s, and 80s are likelier to identify their awareness of Greek-things with Zorba the Greek. Americans growing up today are likelier to identify Greekness with popular films like My Big Fat Greek Wedding which came out in 2002 and its sequel, My Big Fat Greek Wedding 2, which came out in 2022. Both of those films, too, are at the Library. Whatever your taste, or whatever your field of interest, we hope that you have enjoyed this post on modern Greek and the Library of Congress’ modern Greek holdings. Happy celebrating on International Greek Language Day! For any questions about our holdings, feel free to check us out at the Library’s home page, loc.gov.