Animals in ancient Egypt were worshiped as deities, Anubis, a dog and jackal, Horus, a falcon, Bastet, a cat, Sekhmet, a lion, Sobek, a crocodile, Toth, a baboon and ibis. In ancient Greece they were the companions or theomorphic stand-ins for gods and goddesses such as Athena and her owl, Hera and her peacock, Artemis and her deer, Aphrodite and her swan, and Zeus and his eagle. Many animals were considered sacred such as snakes in the worship of Apollo, Dionysus, and Asclepius, pigs in the cult of Demeter, bees and bears in the cult of Artemis.

Before the invention of weapons, our human ancestors were hunted as easy prey animals without fangs and claws to defend themselves and with limited ability to run, jump, and climb. Eventually, with the invention of spears and arrows the tables turned and humans began to hunt other animal species; however, meat, contrary to the stereotypical image of the “cave man,” constituted a very small portion of the prehistoric diet. Most of the food was collected by so called gatherers, often women and children, who collected roots, nuts, seeds, grains, wild mushrooms, wild olives, wild figs, and other wild seeds, fruits and berries. The killed animals, rather than being eaten, may originally have been offered to please or plead with the gods, a custom which continued in ancient Greece and Rome (ca. 1400 BCE-5th century CE). No animal in pagan antiquity was killed strictly for food. The meat was shared by humans and their gods to whom the animals had been sacrificed on special occasions such as religious festivals, which in ancient Greece often included theater/music and athletic competitions, such as at the City Dionysia and the Olympic Games, all to honor particular gods and goddesses.

As human animals went from a nomadic existence to one of settlers and farmers, they began taming and using other animals for their own purposes. After their domestication, bulls, cows, horses, donkeys, sheep, and goats were used to plow fields, to provide milk, transportation, and clothing. Wild boars were hunted for “displays of manhood” by well-to-do young men as were various birds, deer, hares, and lizards. Some animals were made companions or pets such as sparrows, pigeons, doves, dogs, cats, monkeys and, in imperial Rome, even wild animals such as gazelles and cheetahs.

Rabbits, dogs, roosters, and doves were given as presents, also in courtship as “love gifts.” Mice and various kinds of fish were eaten, but they, too could be pets and sacred to the gods. Animals including horses and elephants were used in war, and as entertainment in ancient Rome where lions, tigers, elephants, giraffes, bears, rhinoceroses, hippopotamuses, wild donkeys, hyenas, and ostriches were forced to fight to their deaths.

Greek authors, including Plato, Aristotle, Plutarch, Aelian, and Porphyry, wrote about animals in works on ethics, morals, and natural history. Prose and poetry writers, including Homer, “Aesop,” Herodotus, Lucretius, Oppian, Ovid, Diodorus Siculus, and Dio Cassius, used animals to tell stories and to illustrate the human experience.

Domestication of Animals

One of the earliest animals to be domesticated in the Near East was the goat, judging from evidence from Neolithic (later Stone Age) Jericho, ca. 7000-6000 BCE. Neolithic farmers began to herd wild goats for milk and wool. Their browsing was also useful to clear away brush for planting and to prevent fires. Their dung was used as fuel and building material.

“Billy Goat in a Thicket” from Sumer, Near East, ca. 2600 BCE. Made from gold leaves and lapis lazuli. British Museum.

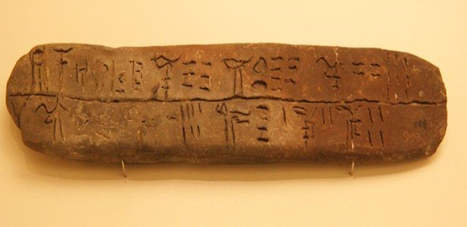

That animals were used in farming by the early Greeks is witnessed by texts on clay tablets from the Mycenaean civilization (ca. 1400-1100 BCE), written in the earliest form of Greek, the so called Linear B script. This tablet was discovered at Knossos on Crete and mentions goats, boars, cows, and bulls. Dated to ca. 1400 BCE.

Animals in Art

Animals in antiquity were represented on pottery, in frescoes, on coins, on temple reliefs, in figurines and sculptures and mosaics as sacred, as symbols, as part of a narrative, and as decoration.

A pod of dolphins on a Minoan fresco from the so called Queen’s Megaron, Knossos, ca. 1500 BCE.

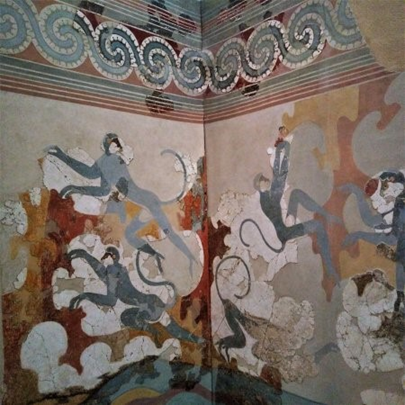

“Blue Monkey” fresco. Thera (Santorini). Room Beta 6. West Wall, ca. 1500 BCE.

The “Lion Gate” leading to the citadel of Mycenae on the Peloponnese is the most recognizable monumental artwork of the early Greek Mycenaean civilization, ca. 1250 BCE.

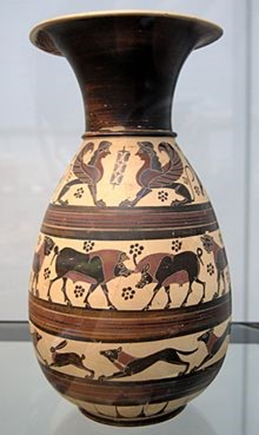

Orientalizing Corinthian oinochoe (wine jug) featuring sphinxes, lions, boars, hares, panthers, ca. 620 BCE. Glyptothek, Munich.

Animals in Post-Classical Book Art

Animals decorated all sorts of texts during the European Middle Ages (ca. 1100-1453 CE) which to a large extent continued the ancient conventions in art and literature but now as marginal fillers or moral lessons rather than as gods or sacred animals with a few possible exceptions such as the dove for the Holy Ghost, the lamb of Jesus Christ, and the three animal symbols (ox, lion, eagle) of the Evangelists. The margins of illuminated medieval manuscripts were frequently filled with every kind of animal, real and imagined. In fact, a technical term for marginal illuminations or “grotesques” is Baboon or Baboyne or Babewyne.

Lizard-leopard and horse-ram-boar composite animals. Liber Floridus (“Flower Book”) is a medieval encyclopedia about plants and animals, in part a “bestiary,” compiled between 1090 and 1120 CE by Lambert, Canon of Saint-Omer. The manuscript is in the Library of the University of Ghent.

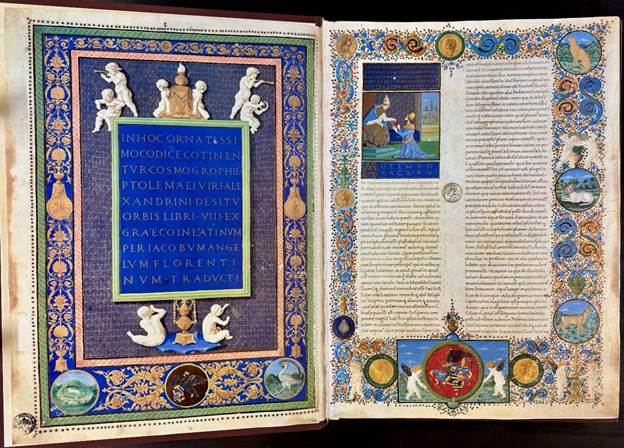

Animals such as a leopard, a dog, a deer, a goose, an eagle, and an ermine are featured in the margins of this renaissance manuscript (Cod. Urb. lat. 277) from 1472 of Ptolemy’s Geography from the 2nd century. Biblioteca Apostolica Vaticana.

Animals as Monsters

The distinction between nature, nonhuman animals, and humans, which characterizes monotheistic religions, was not as sharply drawn among the ancient pagans. The animals featured could be hybrid “fantasy” animals such as the Centaur (horse-man), Sphinx (lion-woman), Hippocamp (fish-horse), Minotaur (bull-man), Griffin (eagle-lion), Typhon (snake-man), Medusa (snake-woman), and Chimaera (lion-goat-snake). Often they were killed or “conquered” by a human male “hero” such as Perseus, Theseus, or Heracles, or a saint like George in the post-classical Christian tradition.

The Chimaera. Etruscan bronze sculpture from Arezzo, ca. 400 BCE. National Archaeological Museum of Florence.

Sacred Animals on Coins

The animals featured on Greek coins were generally associated with a god(ess) and/or eponymous hero.

Owl, the sacred animal of the goddess Athena, on an Athenian silver tetradrachm, ca. 449-404 BCE. The CHS Library.

Ephesus and its bee sacred to Artemis on a silver tetradrachm, ca. 350-340 BCE.

Aegina and its turtle. Silver stater, ca. 445-431 BCE.

Lycia (in modern-day Turkey) and its boar and tortoise. Silver stater, ca. 490-430 BCE.

Lycia could also be represented by a panther or leopard as on this silver hemiobol, ca. 400-390 BCE.

This coin featuring twin panthers or leopards along with a lion on the reverse is also from Lycia. Silver stater, ca. 450-380 BCE. Most figures in ancient art were portrayed in profile, so when they appear with frontal faces as here and as the panther/leopard on the hemiobol, it is thought that they served an apotropaic function, i.e., to ward off evil spirits or bad luck. It could perhaps also be an artistic attempt at breaking with convention.

Syracuse, Sicily, and its nymph goddess Arethusa surrounded by dolphins. Silver tetradrachm, ca. 310 BCE.

Syracuse could also be represented by an octopus as on this Greek silver litra, ca. 466-405 BCE.

Carthage (present-day Tunisia, North Africa) by a horse as on this electrum stater, ca. 310-290 BCE.

Akragas (modern Agrigento, Sicily) by a crab as on this silver didrachm, ca. 495-478 BCE.

Tarentum (modern Taranto, Calabria) by its eponymous founder Taras riding a dolphin. Silver didrachm, ca. 3rd century BCE.

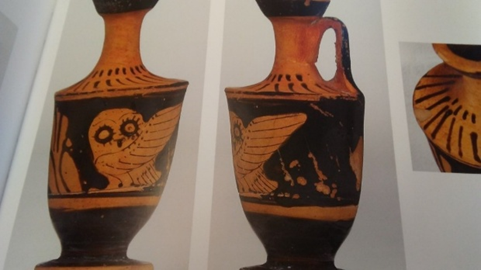

Sacred Animals on Pottery

The goddess Athena’s owl on an Attic skyphos (wine cup), second quarter of 5th century BCE. National Gallery of Victoria, Melbourne.

The Athenian owl on a red-figure lekythos (oil container) from Nola, Southern Italy, ca. 4th century BCE. (Staatliche Museen zu Berlin) Antikensammlung, Berlin.

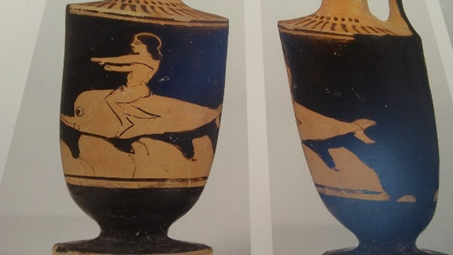

There were many tales in antiquity of people being rescued by dolphins such as Arion, the purported inventor of the dithyramb, which, according to the Greek philosopher Aristotle, was the origin of Greek tragedy, who after being kidnapped by pirates escaped on the back of a dolphin or so the story goes.

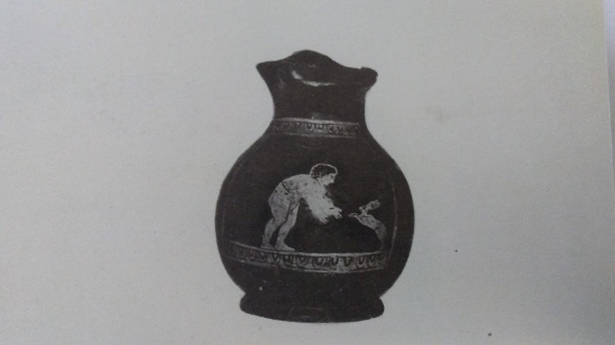

Attic red-figure lekythos with a young man riding on a dolphin, ca. 500-450 BCE. (Staatliche Museen zu Berlin) Antikensammlung, Berlin.

Ritual Blood Sacrifice

“For often in front of the noble shrines of the gods a calf falls slain beside the incense-burning altars, breathing up a hot stream of blood from his breast; but the mother bereaved wanders through the green glens, and seeks on the ground the prints marked by the cloven hooves, as she surveys all the regions if she may espy somewhere her lost offspring, and coming to a stand fills the leafy woods with her moaning, and often revisits the stall, pierced with yearning for her calf; nor can tender willow-growths, and herbage growing rich in the dew, and those rivers flowing level with their banks, give delight to her mind and rebuff her urgent care, nor can the sight of other calves in the happy pastures divert her mind and lighten her load of care: so persistently she seeks for something of her own that she knows well” (Lucretius, De Rerum Natura 352-366).

“Animals retain the memory of their experiences and have no need of those mnemonic systems devised by Simonides, by Hippias, and by Theodectes, or by any other of those who have been extolled for their profession and their skill in this matter. For instance, a cow goes to the spot where her calf was taken from her and mourns for it, lowing as is her wont” (Aelian, On the Nature of Animals 6.10[ii]).

“Now the purple coot, in addition to being extremely jealous, has, I believe, this peculiarity; they say that it is devoted to its own kin and loves the company of its mates. At any rate I have heard that a purple coot and a cock were reared in the same house that they fed together, that they walked step for step, and that they dusted in the same spot. From these causes there sprang up a remarkable friendship between them. And one day on the occasion of a festival their master sacrificed the cock and made a feast with his household. But the purple coot, deprived of its companion and unable to endure the loneliness, starved itself to death” (Ael. NA 5.28).

The sacrifice of animals to various deities was quite common although not as frequent as Christians would later contend. It was generally limited to large official and formal religious ceremonies. Most everyday offerings were in the form of libations and fruits, seeds, and nuts. Some ancient Greeks and Romans as well as modern scholars have theorized that animal sacrifice had its origin in human sacrifice to placate a deity in times of extreme danger such as during an earthquake, war, or famine. If this was so, it is unclear how and when it became more “commonplace” or when nonhuman animals were substituted for human.

“…The Ionians who lived in Aroë, Antheia and Mesatis had in common a precinct and a temple of Artemis surnamed Triclaria, and in her honour the Ionians used to celebrate every year a festival and an all-night vigil. The priesthood of the goddess was held by a virgin until the time came for her to be sent to a husband. Now the story is that once upon a time it happened that the priestess of the goddess was Comaetho, a most beautiful virgin, who had a lover called Melanippus, who was far better and handsomer than his fellows… The history of Melanippus, like that of many others, proved that love is apt both to break the laws of men and to desecrate the worship of the gods, seeing that this pair had their fill of the passion of love in the sanctuary of Artemis…Forthwith the wrath of Artemis began to destroy the inhabitants; the earth yielded no harvest, and strange diseases occurred of an unusually fatal character. When they appealed to the oracle at Delphi the Pythian priestess accused Melanippus and Comaetho. The oracle ordered that they themselves should be sacrificed to Artemis, and that every year a sacrifice should be made to the goddess of the fairest youth and the fairest maiden…” (Pausanias 7.19).

“For it is customary among the barbarians who inhabit this land to sacrifice to Artemis Tauropolus the strangers who put in there, and it is among them, they say, that at a later time Iphigeneia became a priestess of this goddess and sacrificed to her those who were taken captive” (Diodorus Siculus 4.44).

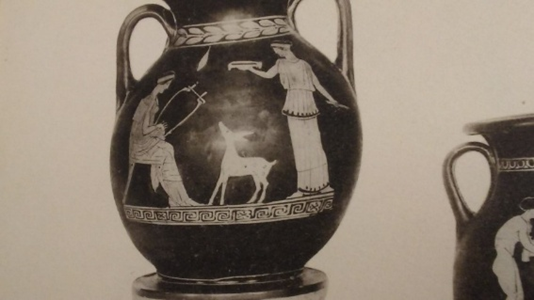

The most famous human sacrifice in classical antiquity was that of the virgin Iphigenia, the daughter of Agamemnon, one of the Greek kings from the Trojan War. Although there are different versions of the ending, one of the most popular was told by the Greek playwright Euripides (ca. 480–ca. 406 BCE) who had the goddess Artemis, to whom the sacrifice had been offered in the first place, substitute the human girl for a deer, which perhaps could be interpreted as an allegory for an actual development from human to animal sacrifice. There are many references to human sacrifice in Greek literature and archaeological evidence pointing to such sacrifice has been unearthed in several places on Minoan-Mycenaean Crete (Myrtos, Knossos, Archanes, Chania) and at Etruscan Tarquinia.

Iphigenia at the moment of substitution for a deer. Volute crater, ca. 370-355 BCE. British Museum.

Animals as Food

In ancient Greece, only animals sacrificed to the gods could be eaten after a portion of the animal was given to a particular deity or deities. The everyday staple foods of ordinary Greeks were mainly plant based which kept them strong and healthy. After all many of the largest, strongest, and most fierce animals, elephants, bulls, oxen, gorillas, rhinos, hippos, horses, are plant eaters. In fact, some ancient Greeks objected to eating any meat at all.

“Can you really ask what reason Pythagoras had for abstaining from flesh? For my part I rather wonder both by what accident and in what state of soul or mind the first man who did so, touched his mouth to gore and brought his lips to the flesh of a dead creature, he who set forth tables of dead, stale bodies and ventured to call food and nourishment the parts that had a little before bellowed and cried, moved and lived. How could his eyes endure the slaughter when throats were slit and hides flayed and limbs torn from limb? How could his nose endure the stench?” (Plutarch, Moralia, On the Eating of Flesh 993a-b).

“Are you not ashamed to mingle domestic crops with blood and gore? You call serpents and panthers and lions savage, but you yourselves, by your own foul slaughters, leave them no room to outdo you in cruelty; for their slaughter is their living, yours is a mere appetizer” (Plut. Mor. On the Eating of Flesh 994a-b).

“But nothing abashed us, not the flower-like tinting of the flesh, not the persuasiveness of the harmonious voice, not the cleanliness of their habits or the unusual intelligence that may be found in the poor wretches. No, for the sake of a little flesh we deprive them of sun, of light, of the duration of life to which they are entitled by birth and being. Then we go on to assume that when they utter cries and squeaks their speech is inarticulate, that they do not, begging for mercy, entreating, seeking justice…” (Plut. Mor. On the Eating of Flesh 994e).

“…it is absurd for them to say that the practice of flesh-eating is based on Nature. For that man is not naturally carnivorous is, in the first place, obvious from the structure of his body. A man’s frame is in no way similar to those creatures that were made for flesh-eating: he has no hooked beak or sharp nails or jagged teeth, no strong stomach or warmth of vital fluids able to digest and assimilate a heavy diet of flesh. It is from this very fact, the evenness of our teeth, the smallness of our mouths, the softness of our tongues, our possession of vital fluids too inert to digest meat that Nature disavows our eating of flesh” (Plut. Mor. On the Eating of Flesh 994f-995a).

“If you declare that you are naturally designed for such a diet, then first kill for yourself what you want to eat. Do it, however, only through your own resources …just as wolves and bears and lions themselves slay what they eat, so you are to fell an ox with your fangs or a boar with your jaws or tear a lamb or hare in bits. Fall upon it and eat it still living, as animals do” (Plut. Mor. On the Eating of Flesh 995a-b).

“…Even when it is lifeless and dead, however, no one eats the flesh just as it is; men boil it and roast it, altering it by fire and drugs, recasting and diverting and smothering with countless condiments the taste of gore so that the palate may be deceived and accept what is foreign to it” (Plut. Mor. On the Eating of Flesh 995b).

“…All things were free from treacherous snares, fearing no guile and full of peace. But after someone, an ill exemplar, whoever he was, envied the food of lions, and thrust down flesh as food into his greedy stomach, he opened the way for crime” (Ovid, Metamorphoses 15.102-103).

“Further impiety grew out of that, and it is thought that the sow was first condemned to death as a sacrificial victim because with her broad snout she had rooted up the planted seeds and cut off the season’s promised crop. The goat is held fit for sacrifice at the avenging altars because he had browsed the grape-vines” (Ov. Met. 15.111-115).

“…But, ye sheep, what did you ever do to merit death, a peaceful flock…that bring us sweet milk to drink in your full udders, who give us your wool for soft clothing, and who help more by your life than by your death? What have the oxen done, those faithful, guileless beasts, harmless and simple, born to a life of toil?” (Ov. Met. 15.116-121).

“Nor is it enough that we commit such infamy: they made the gods themselves partners of their crime and they affected to believe that the heavenly ones took pleasure in the blood of the toiling bullock! A victim without blemish and of perfect form (for beauty proves his bane), marked off with fillets and with gilded horns, is set before the altar, hears the priest’s prayer, not knowing what it means, watches the barley-meal sprinkled between his horns, barley which he himself labored to produce, and then, smitten to his death, he stains with his blood the knife which he has perchance already seen reflected in the clear pool. Straightway they tear his entrails from his living breast, view them with care, and seek to find revealed in them the purposes of heaven” (Ov. Met. 15.127-137).

Some advocated for the shunning of animal products altogether.

“If…someone should…think it is unjust to destroy brutes, such a one should neither use milk, nor wool, nor sheep, nor honey. For, as you injure a man by taking from him his garments, thus, also, you injure a sheep by shearing it. For the wool which you take from it is its vestment. Milk, likewise, was not produced for you, but for the young of the animal that has it. The bee also collects honey as food for itself; which you, by taking away, administer for your own pleasure” (Porphyry, On Abstinence 1.21).

Animals in Entertainment

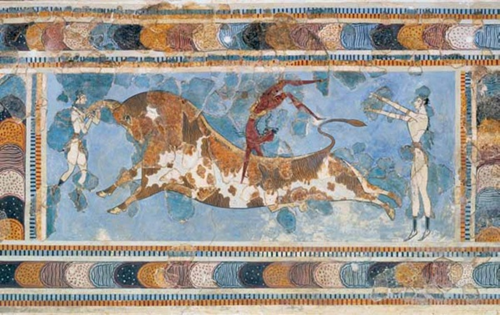

Minoan women (painted white) and men (painted red-brown) participated in acrobatic “performances,” which involved jumping over bulls. The bulls, however, were not killed as in contemporary Spanish bullfights but were sacred to the Minoans.

The “Bull-leaping fresco” from the East Wing of the “Palace” of Knossos, ca. 1600-1400 BCE.

Some Roman emperors relished in animal (also human) killings in the arena.

Hippos, Rhinos, Elephants

“[Roman Emperor] Commodus devoted most of his life to ease and to horses and to combats of wild beasts and of men. In fact, besides all that he did in private, he often slew in public large numbers of men and of beasts as well. For example, all alone with his own hands, he dispatched five hippopotami together with two elephants on two successive days; and he also killed rhinoceroses and a camelopard [giraffe]” (Dio Cassius, Roman History 73.10.3).

200 lions

“On his birthday he [Emperor Hadrian] gave the usual spectacle free to the people and slew many wild beasts, so that one hundred lions, for example, and a like number of lionesses fell on this single occasion” (Dio Cass. Roman History 69.8.1).

500 lions, 18 elephants and human deception

“During these same days Pompey dedicated the theater in which we take pride even at the present time. In it he provided entertainment consisting of music and gymnastic contests and in the Circus a horse-race and the slaughter of many wild beasts of all kinds. Indeed, five hundred lions were used up in five days, and eighteen elephants fought against men in heavy armor. Some of these beasts were killed at the time and others a little later. For some of them, contrary to Pompey’s wish, were pitied by the people when, after being wounded and ceasing to fight, they walked about with their trunks raised toward heaven, lamenting so bitterly as to give rise to the report that they did so not by mere chance, but were crying out against the oaths in which they had trusted when they crossed over from Africa, and were calling upon Heaven to avenge them. For it is said that they would not set foot upon the ships before they received a pledge under oath from their drivers that they should suffer no harm” (Dio Cass. Roman History 38).

700 wild boars, elephants, hyena, ostriches, bison, panthers, wild asses

“At these spectacles [10th anniversary of Emperor Severus’ power] sixty wild boars of Plautianus fought together at a signal and among many other wild beasts that were slain were an elephant and a corocotta [hyena]. This last animal is an Indian species and was then introduced into Rome for the first time, so far as I am aware. It has the color of a lioness and tiger combined, and the general appearance of those animals, as also of a dog and a fox, curiously blended. The entire receptacle in the amphitheater had been constructed so as to resemble a boat in shape, and was capable of receiving or discharging four hundred beasts at once; and then, as it suddenly fell apart, there came rushing forth bears, lionesses, panthers, lions, ostriches, wild asses, bison (this is a kind of cattle foreign in species and appearance), so that seven hundred beasts in all, both wild and domesticated, at one and the same time were seen running about and were slaughtered” (Dio Cass. Roman History 77).

“To Alexander he presented many impressive gifts, among them one hundred and fifty dogs remarkable for their size and courage and other good qualities. People said that they had a strain of tiger blood. He wanted Alexander to test their mettle in action, and he brought into a ring a full-grown lion and two of the poorest of the dogs. He set these on the lion, and when they were having a hard time of it, he released two others to assist them. The four were getting the upper hand over the lion when Sopeithes sent in a man with a scimitar who hacked at the right leg of one of the dogs. At this Alexander shouted out indignantly and the guards rushed up and seized the arm of the Indian, but Sopeithes said that he would give him three other dogs for that one, and the handler, taking a firm grip on the leg, severed it slowly. The dog, in the meanwhile, uttered neither yelp nor whimper, but continued with his teeth clamped shut until, fainting with loss of blood, died on top of the lion” (Diod. Sic. 17.92).

Bastet, the Egyptian Cat Goddess

Cats are generally believed to have been domesticated in ancient Egypt some 4,000 years ago; however, evidence suggests that the cat may have been part of the household in the Near East already some 14,000 years ago along with sheep, goats, and dogs.

Cats and lions were sacred in ancient Egypt. There was even a cat goddess, Bastet. Cats were used both as pets and mousers. Many cat owners had their cats mummified to accompany them in death, although mummified cats and cat figurines were mostly given as offerings to the immensely popular cat goddess at her temple in Bubastis (Tell Basta), where amulets and votive figurines of the goddess were mass produced and festivals were held with wine, song and dance in her honor.

“…when they have reached Bubastis, they make a festival with great sacrifices, and more wine is drunk at this feast than in the whole year beside. Men and women (but not children) are wont to assemble there to the number of seven hundred thousand, as the people of the place say” (Herodotus 2.60).

“…is there anyone who doesn’t know the kind of monsters that crazy Egypt worships? One district reveres the crocodile, another fears the ibis, glutted with snakes. The sacred long-tailed monkey’s golden image gleams… Entire towns venerate cats in one place, in another river fish, in another a dog…It’s a violation and a sin to bite into a leek or an onion. Such holy peoples, to have these gods growing in their gardens! Their tables abstain completely from woolly animals, and there it’s a sin to slaughter a goat’s young. But feeding on human flesh is allowed” (Juv. Satire 15).

Cat with kittens. Egypt, ca. 664-30 BCE. Brooklyn Museum.

“And whoever intentionally kills one of these animals is put to death, unless it be a cat or an ibis that he kills; if he kills one of these [cats], whether intentionally or unintentionally, he is certainly put to death, for the common people gather in crowds and deal with the perpetrator most cruelly, sometimes doing this without waiting for a trial. And because of their fear of such a punishment any who have caught sight of one of these animals lying dead withdraw to a great distance and shout with lamentations and protestations that they found the animal already dead. So deeply implanted also in the hearts of the common people is their superstitious regard for these animals and so unalterable are the emotions cherished by every man regarding the honor due to them that once, at the time when Ptolemy their king had not as yet been given by the Romans the appellation of “friend” and the people were exercising all zeal in courting the favor of the embassy from Italy which was then visiting Egypt and, in their fear, were intent upon giving no cause for complaint or war, when one of the Romans killed a cat and the multitude rushed in a crowd to his house, neither the officials sent by the king to beg the man off nor the fear of Rome which all the people felt were enough to save the man from punishment, even though his act had been an accident. And this incident we relate, not from hearsay, but we saw it with our own eyes on the occasion of the visit we made to Egypt” (Diod. Sic. 1.83.1-8).

The so called Gayer-Anderson Cat (the cat goddess Bastet) from ancient Egypt, Late Period ca. 664-332 BCE. Made of bronze with gold ornaments. British Museum.

“And when a fire breaks out very strange things happen to the cats. The Egyptians stand around in a broken line, thinking more of the cats than of quenching the burning; but the cats slip through or leap over the men and spring into the fire. When this happens, there is great mourning in Egypt. Dwellers in a house where a cat has died a natural death shave their eyebrows and no more; where a dog has so died, the head and the whole body are shaven” (Herodotus 2.66-2.67).

“Dead cats are taken away into sacred buildings, where they are embalmed and buried, in the town of Bubastis; female dogs are buried in sacred coffins by the townsmen, in their several towns; and the like is done with ichneumons [wasps]. Shrewmice and hawks are taken away to Buto, ibises to the city of Hermes. There are but few bears, and the wolves are little bigger than foxes; both these are buried wherever they are found lying” (Hdt. 2.67).

Egyptian cat goddess Bastet, ca. 664-30 BCE. Made of leaded bronze. Metropolitan Museum of Art.

“When one of these animals dies, they wrap it in fine linen and then, wailing and beating their breasts, carry it off to be embalmed; and after it has been treated with cedar oil and such spices as have the quality of imparting a pleasant odor and of preserving the body for a long time, they lay it away in a consecrated tomb” (Diod. Sic. 1.83.5-6).

Numerous cat mummies were found in the desert at Beni Hassan, about a hundred miles from Cairo in the late 1800s. Most were sold on the private antiquities market.

Mother cat and kittens on a faience ring from Egypt, ca. 1295–664 BCE. Metropolitan Museum of Art.

The lion was also worshiped as a god in ancient Egypt.

The lion goddess Sekhmet, ca. 1390-1352 BCE. Metropolitan Museum of Art.

Animals as Pets

Companion animals or pets were popular also in antiquity, especially dogs and cats, but among the Egyptians also baboons, various kinds of monkeys, fish, gazelles, birds, lions, mongoose, hippos, etc., and among the Greeks and Romans, apart from cats and dogs also rabbits, snakes, doves, herons, cranes, chickens, ducks, geese, magpies, quails, peacocks, pigeons, parrots, nightingales, and other birds, and, among wealthy Romans, possibly even deer, cheetahs, leopards, and lions.

Dogs

The most famous dog in ancient Greece was Argus, the loyal and faithful dog that recognizes his disguised guardian, the long-lost Greek hero from the Trojan War, Odysseus, in the Homeric epic the Odyssey (8th century BCE) whereupon he dies. Knowing that his guardian was alive and well after being gone for some twenty years allowed the ailing and aged dog Argus to finally give up the ghost.

“There lay the dog Argus, full of dog ticks. But now, when he became aware that Odysseus was near, he wagged his tail and dropped both ears, but nearer to his master he had no longer strength to move. Then Odysseus looked aside and wiped away a tear, easily hiding from Eumaeus what he did; and immediately he questioned him, and said: Eumaeus, truly it is strange that this dog lies here in the dung. He is fine of form, but I do not clearly know whether he had speed of foot to match this beauty or whether he is merely as table dogs are, which their masters keep for show” (Homer, Odyssey 17.290-327).

“To him then, swineherd Eumaeus, did you make answer and say: “Yes, truly this is the dog of a man who has died in a far land. If he were but in form and action such as he was when Odysseus left him and went to Troy, you would soon be amazed at seeing his speed and his strength…” (Hom. Od. 17. 290-327).

“…But as for Argus, the fate of black death seized him once he had seen Odysseus in the twentieth year” (Hom. Od. 17. 326-27).

The dog Argus on a silver denarius, 82 BCE. This image of a young and energetic Argus does not correspond well with the portrait of the old and sick dog from the Odyssey.

“They say that Poliarchus the Athenian arrived at so great a height of Luxury, that he caused those dogs and cocks which he had loved, being dead, to be carried out solemnly, and invited friends to their Funerals, and buried them splendidly, erecting Columns over them, on which were engraved Epitaphs” (Ael. VH 8.4).

A tombstone with a sculpted dog holds an epitaph to a dog named Helena, dated to 150-200 CE, now at the Getty Villa in Los Angeles. The Latin inscription reads: “To Helena, foster daughter, incomparable and trustworthy soul.”

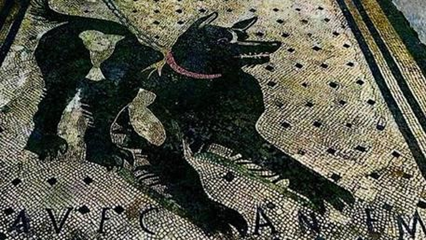

This mosaic from Pompeii depicts a chained guard dog with the inscription Cave Canem (Be aware of the dog), terminus ante quem 79 CE.

A guard dog who because it was chained could not escape the ashes of the volcanic eruption of Vesuvius that buried the town of Pompeii in 79 CE and so died in agony.

Cats

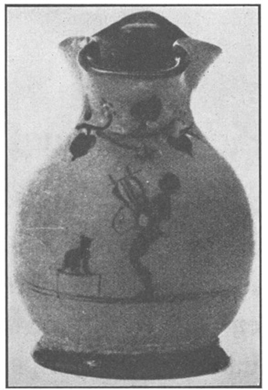

On a Boeotian toy oinochoe a boy plays the lyre for the amusement of his cat that sits on a small stool and listens attentively. Antikensammlung, Berlin.

Hares

“They [the Britanni] account it wrong to eat hare, fowl, and goose; but these they keep for pastime or pleasure” (Caesar, Gallic Wars 5.2).

A boy, wearing a band of amulets around his body, holds out his arms to a hare which is standing on its hind legs to greet its guardian. Ny Carlsberg Glyptotek, Copenhagen.

Snakes

“As a drinking and living companion he [Ajax] had a tame snake that was five cubits long, which led the way when he traveled and otherwise followed him like a dog” (Philostratus, Heroicus 31.3).

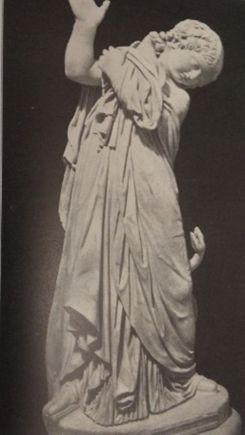

This Greek life-size Hellenistic marble statue features a young girl lifting her pet pigeon away from her pet snake to protect it. Capitoline Museums, Rome.

Pigeons

Greek marble stele depicting a girl kissing her pet pigeon. Metropolitan Museum of Art, ca. 450-440 BCE.

Fishes

Some had individual fishes as pets.

“It seems that even fishes are both tame and tractable, and when summoned can hear and are ready to accept food that is given them, like the sacred eel in the Fountain of Arethusa. And men tell of the moray belonging to Crassus the Roman, which had been adorned with earrings and small necklaces set with jewels, just like some lovely maiden; and when Crassus called it, it would recognize his voice and come swimming up, and whatever he offered it, it would eagerly and promptly take and eat. Now when this fish died, Crassus, so I am told, actually mourned for it and buried it. And on one occasion when Domitius said to him ‘You fool, mourning for a dead moray!’ Crassus took him up with these words: ‘I mourned for a moray, but you never mourned for the three wives you buried” (Aelian, On the Nature of Animals 8.4[i]).

“Tame fishes which answer to a call and gladly fish of various lands accept food are to be found and are kept in many places; in Epirus for instance, at the town, formerly called Stephanopolis, in the temple of Fortune in the cisterns on either side of the ascent; at Helorus too in Sicily which was once a Syracusan fortress; and at the shrine of Zeus of Labranda in a spring of transparent water. And there fish have golden necklaces and earrings also of gold…And in Chios in what is called ‘The Old Men’s Harbor’ there are multitudes of tame fish, which the inhabitants of Chios keep to solace the declining years of the very aged” (Ael. NA 12.30).

“Fish employ cunning wit and deceitful craft and often deceive even the wise fishermen themselves and escape from the might of hooks and from the belly of the trawl when already caught in them and outrun the wits of men; outdoing them in craft and become a grief to the fishermen” (Oppian, Halieutica 3.92-98).

Animals as Courtships Gifts

Various animals could be given as presents; others may represent symbolic gifts, such as the rooster, hare, dove, and fawn between two lovers whether the couples were mythological creatures or real, whether of the same or opposite sex.

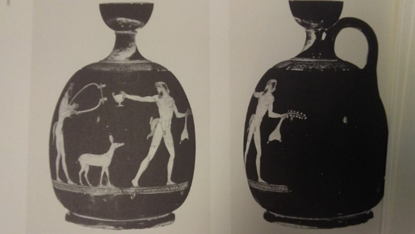

A fawn as a “love gift” between two human males. Attic red-figure skyphos (wine cup), ca. 460-450 BCE. The Louvre Painter. Antikensammlung, Berlin.

A fawn as a “love gift” between two human females. Attic red-figure pelike (liquid container), ca 450-400 BCE. Ny Carlsberg Glyptotek, Copenhagen.

Animals as Theomorphic Symbols

“In this Chrysa is also the temple of Sminthian, the symbol which preserves the etymology of the name, Ι mean the mouse, lies beneath the foot of his image. These are the works of Scopas of Paros; and also the history, or myth, about the mice is associated with this place: When the Teucrians arrived from Crete (Callinus the elegiac poet was the first to hand down an account of these people, and many have followed him), they had an oracle which bade them to “stay on the spot where the earth-born should attack them”; and, he says, the attack took place round Hamaxitus, for by night a great multitude of field-mice swarmed out of the ground and ate up all the leather in their arms and equipment; and the Teucrians remained there; and it was they who gave its name to Mt. Ida, naming it after the mountain in Crete. Heracleides of Pontus says that the mice which swarmed round the temple were regarded as sacred, and that for this reason the image was designed with its foot upon the mouse” (Strabo, Geography 13.1.48).

Bronze figurine of a mouse dedicated to Apollo Smintheus (the Mouse God). (Staatliche Museen zu Berlin) Antikensammlung, Berlin.

Artemis, the Goddess of Nature

The famous cult statue of Artemis and her temple at Ephesus, now in modern-day Turkey, were counted among the Seven Wonders of the ancient world. The statue is full of animals — on the goddess’ dress, headgear, and sandals. The identification of the bulbous protrusions in the front has been hotly debated. The most logical interpretation is of the Goddess of Nature nursing all her children – animals and plants alike — or possibly seeds to feed life. The temple’s beehive organization with priestesses called bees and priests drones may point to a representation of eggs. A wildly speculative theory is that they represent bull scrota.

A replica of the cult statue of Ephesian Artemis in the Museum of Ephesus. The earliest temple and statue date back to the Bronze Age although this copy is dated much later. Christians eventually destroyed the temple and statue in the 5th century CE.

Artemis of Ephesus worshiped “in Asia and all the world.” A Roman copy of an original from the 2nd century BCE. Capitoline Museums, Rome.

Hunting in classical Greece was mostly an activity among upper class young males for “sport” or “proof of manhood” rather than among farmers or workers for food.

“Game and hounds are the invention of gods, of Apollo and Artemis. They bestowed it on Cheiron and honoured him therewith for his righteousness. And he, receiving it, rejoiced in the gift, and used it. And he had for pupils in venery and in other noble pursuits—Cephalus, Asclepius, Meilanion, Nestor, Amphiaraus, Peleus, Telamon, Meleager, Theseus, Hippolytus, Palamedes, Odysseus, Menestheus, Diomedes, Castor, Polydeuces, Machaon, Podaleirius, Antilochus, Aeneas, Achilles, of whom each in his time was honoured by gods” (Xen. Cyn. 1.1-2).

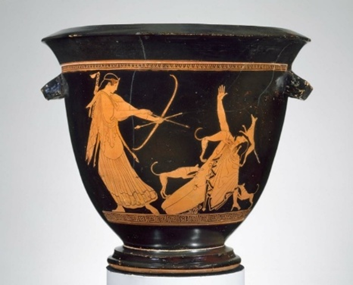

(Artemis’s Sacred) Deer

Of the story about Alcaeus, there are many versions. A children’s cartoon on American TV a couple of years ago, featured the story of the goddess Artemis and the hunter Actaeon, loosely based on Ovid’s tale in the Metamorphoses. This version described how the Greek goddess Artemis transformed the hunter Actaeon into a stag to teach him a lesson about not killing animals. The terrified Actaeon, now a deer, attempts to speak but is not able to make himself understood without a human language. As his hunting companions are poised to throw their spears and shoot their arrows and the hunting dogs are about to pounce at the “deer” Actaeon, he promises Artemis that if she would only change him back into human form, he would never kill another living being and instead educate his hunting companions about the plight and suffering of hunted animals, which indeed was the happy outcome.

Artemis shooting at Actaeon with his own hunting dogs attacking, seeing him as a deer. Bell krater to mix water and wine by the so-called Pan Painter, ca. 470 BCE. Museum of Fine Arts, Boston.

“Artemis and a Stag.” European female (roe) deer may sometimes also sport antlers, so it could be a doe. Roman copy of a sculpture by Greek artist Leochares from ca. 325 BCE. Louvre.

Artemis’/Diana’s deer on a Roman billon Antoninianus, from the reign of Emperor Gallienus, ca. 267/268 CE. DIANAE CONSERVATORI AVGVSTI (to Diana (Artemis), the Preserver of the Emperor).

Wild Animals

The story about the legendary poet and prophet from Thrace (today bordering Bulgaria, Greece, Turkey), Orpheus, and the many wild animals that came to listen to him playing the lyre was popular already in antiquity. In addition to his musical rapport with wild animals, Orpheus taught nonviolence and opposed the killing of any living being.

“Just consider how beneficial the noble poets have been from the earliest times. Orpheus revealed mystic rites to us, and taught us to abstain from killings” (Ar. Ran. 1030-34).

“Orpheus Taming Wild Animals.” Mosaic. Eastern Roman Empire, near Edessa. 194 CE. Dallas Museum of Art.

A Scythian fibula (broch) in the shape of a deer. Northern Caucasus. Made of gold, late 7th century BCE. Hermitage, Saint Petersburg.

Etruscan perfume bottle in the figure of a boar, ca. 600-500 BCE. Cleveland Museum of Art, Ohio.

Monkies

“Under the Ptolemies the Egyptians taught baboons their letters, how to dance, how to play the flute and the harp. And a baboon would demand money for these accomplishments, and would put what was given him into a bag which he carried attached to his person, just like professional beggars” (Aelian, On the Nature of Animals, 6.10[i]).

Ants

“A matter obvious to everyone is the consideration ants show when they meet: those that bear no load always give way to those who have one and let them pass. Obvious also is the manner in which they gnaw through and dismember things that are difficult to carry or to convey past an obstacle, in order that they may make easy loads for several” (Plutarch, On the Intelligence of Animals 967f).

“But what goes beyond any other conception of their intelligence is their anticipation of the germination of wheat. You know, of course, that wheat does not remain permanently dry and stable, but expands and lactifies in the process of germination. In order, then, to keep it from running to seed and losing its value as food, and to keep it permanently edible, the ants eat out the germ from which springs the new shoot of wheat” (Plut. Mor. De soll. an. 968a).

Elephants

“The elephant is the largest of them all, and in intelligence approaches the nearest to man. It understands the language of its country, it obeys commands, and it remembers all the duties which it has been taught. It is sensible alike of the pleasures of love and glory, and, to a degree that is rare among men even, possesses notions of honesty, prudence, and equity; it has a religious respect also for the stars, and a veneration for the sun and the moon” (Plin. HN 8.1).

Wild Animals in Rites of Passage

Statue of a Bear Cub. 4th century BCE. Acropolis Museum.

Human girls becoming “Bears“

This bear probably belonged to Artemis Brauronia, to whom girls from Athens and neighboring areas dedicated bear statues and figurines and participated in bear rituals (the Arkteia) to celebrate menarche and the transition from girlhood to womanhood. The chorus in Lysistrata recounts the many rites of passage festivals in which girls and young women participated, of which being a bear at Brauron was one, “ἄρκτος ἦ Βραυρωνίοις” (Ar. Lys. 644). In Larissa and neighboring areas in Thessaly similar rituals took place for Artemis Throsia for whom girls and adolescents were fawns (the Nebreia). Boys at the Artemis Ortheia sanctuary in Sparta were foxes.

Human boys becoming “Foxes”

Boys in Sparta, during rites of passage ceremonies, fasted almost to the point of starvation and were supposed to steal to fill their bellies. During this phase of the ceremonies at the Artemis Ortheia sanctuary in Sparta, the boys were referred to as foxes.

“The boys make such a serious matter of their stealing, that one of them, as the story goes, who was carrying concealed under his cloak a young fox which he had stolen, suffered the animal to tear out his bowels with its teeth and claws, and died rather than have his theft detected” (Plut. Vit. Lyc. 18.51).

Terracotta figurine of a fox scratching its head. Tanagra, Boeotia, ca. 5th century BCE. Museum of Fine Arts, Boston.

The ancient Greek relationship to the natural world and polytheistic, almost pantheistic (river gods, tree nymphs) beliefs, and, in this case, the Spartan devotion to a powerful goddess (Artemis Ortheia) and the Spartan male embodiment of a wild animal, and the Athenian devotion to the same powerful goddess under a different name and aspect (Artemis Brauronia) and the Athenian female embodiment of a wild animal were essential elements in coming of age ceremonies in ancient Greece.

Select Bibliography

Aelian. De Natura animalium: On the Characteristics of Animals. Greek and English with an English translation by A.F. Scholfield. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1958-1959.

Albertus Magnus. De animalibus. On Animals: A Medieval Summa Zoologica, translated and annotated by Kenneth F. Kitchell, Jr., and Irven Michael Resnick. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1999.

Aristotle’s Generation of Animals: A Critical Guide. Andrea Falcon and David Lefebvre (eds.). Cambridge; New York: Cambridge University Press, 2018.

Brewer, Douglas J., Donald B. Redford, and Susan Redford. Domestic Plants and Animals: The Egyptian Origins. Warminster: Aris & Phillips, 1994.

Calder, Louise. Cruelty and Sentimentality: Greek Attitudes to Animals, 600-300 BC. Oxford: Archaeopress, 2011.

Chiens et chats dans la préhistoire et l’antiquité. Claire Bellier, Laureline Cattelain and Pierre Cattelain (eds.). Treignes: Éditions du Cedarc, 2015.

Collins, Billie Jean. A History of the Animal World in the Ancient Near East. Leiden; Boston: Brill, 2002.

De l’aigle à la louve: Monnaies et gemmes antiques entre art, propagande et affirmation de soi. Matteo Campagnolo and Carlo-Maria Fallani (eds.). Geneva: Musée d’art et d’histoire de Genève, 2018.

Ferris, Iain. Cave Canem: Animals and Roman Society. Gloucestershire: Amberley, 2018.

Gilhus, Ingvild Sælid. Animals, Gods and Humans: Changing Attitudes to Animals in Greek, Roman and Early Christian Ideas. London; New York: Routledge, 2006.

Harden, Alastair. Animals in the Classical World: Ethical Perspectives from Greek and Roman Texts. Houndmills, Basingstoke, Hampshire; New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2013.

Interactions Between Animals and Humans in Graeco-Roman Antiquity. Thorsten Fögen and Edmund Thomas (eds.). Berlin; Boston: Walter de Gruyter, 2017.

Kitchell, Jr., Kenneth F. Animals in the Ancient World from A to Z. Abingdon, Oxon: Routledge, 2014.

Korhonen, Tua, and Erika Ruonakoski. Human and Animal in Ancient Greece: Empathy and Encounter in Classical Literature. London; New York: I.B. Tauris, 2017.

Llewellyn-Jones, Lloyd. The Culture of Animals in Antiquity: A Sourcebook with Commentaries. Milton Park, Abingdon; New York: Routledge, 2017.

Lonsdale, Steven. Animals and the Origins of Dance. New York: Thames and Hudson, 1981.

Marciniak, Przemysław, and Tristan Schmidt. The Routledge Handbook of Human-Animal Relations in the Byzantine World. Routledge History Handbooks. Routledge, Taylor & Francis Group, 2025.

Masson, Jeffrey Moussaief, and Susan McCarthy. When Elephants Weep: The Emotional Lives of Animals. New York: Delacorte, 1995.

Mensch und Tier in der Antike: Grenzziehung und Grenzüberschreitung : Symposion vom 7. bis 9. April in Rostock. Annetta Alexandridis, Markus Wild und Lorenz Winkler-Horacek (eds.). Wiesbaden: Reichert Verlag, 2008.

Mynott, Jeremy. Birds in the Ancient World. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2018.

Newmyer, Stephen T. Animals in Greek and Roman Thought: A Sourcebook. London; New York: Routledge, 2011.

The Oxford Handbook of Animals in Classical Thought and Life. Campbell, Gordon Lindsay (ed.). Oxford Handbooks. Oxford University Press, 2014.

Plato’s Animals: Gadflies, Horses, Swans, and other Philosophical Beasts. Jeremy Bell and Michael Naas (eds.). Bloomington and Indianapolis: Indiana University Press, 2015.

Plutarch’s Three Treatises on Animals: A Translation with Introductions and Commentary by Stephen T. Newmyer. Abingdon, Oxon; New York, NY: Routledge, 2021.

Porphyry. De abstinentia. On Abstinence from Killing Animals; translated by Gillian Clark. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 2000.

Richter, Gisela. Animals in Greek Sculpture, a Survey. New York; Oxford University Press, 1930.

Rothfels, Nigel. Elephant Trails: A History of Animals and Cultures. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2021.

Sagiv, Idit. Representations of Animals on Greek and Roman Engraved Gems: Meanings and Interpretations. Oxford: Archaeopress, 2018.

Smith, Steven D. Man and Animal in Severan Rome. Cambridge; New York: Cambridge University Press, 2014.

Speaking Animals in Ancient Literature. Hedwig Schmalzgruber (ed.). Heidelberg: Universitätsverlag Winter, 2020.