Sure, the best is water

An “esthetics of fluidity” in classical poetry

τοῦ δ’ ἔπε’ ἐκ στόματος ῥεῖ μείλιχα

For this man [=for this ideal king] they [=the Muses] pour sweet dew,

and from his [=the king’s] mouth flow sweet words.

Further Hesiodic lines vividly exploit the same image. [2] However, this passage features two semantic links with particular emphasis. One is the mention of the source of the flow—or, to be more precise, the double source, namely the Muses first, and consequently the kings’ mouth—where sweet words-in-performance originate. [3] The second feature is the reference to dew in connection with the ideal king. The latter will be commented on later. Nagy emphasizes the former (the idea of source) in terms of presupposition of the flow (“…the motion itself must have an origin, a beginning. The flow needs to have a source”) and in terms of perfection of the flow (“…the theme of fluidity expresses the idea that the humnos must have a perfect beginning. The humnos flows from a perfect source, and so it becomes the perfect performance.”). [4]

δακρυόφιν τέρσοντο, κατείβετο δὲ γλυκὺς αἰὼν

νόστον ὀδυρομένῳ, (…)

and found him sitting on the seashore, and his eyes were never

wiped dry of tears, and the sweet αἰών was draining out of him

as he wept for νόστος (…)

Life and death are intimately bound together at that particular point in Odysseus’ travels; they are almost indistinguishable. [6] And the motif of tears is curiously associated with the flowing down of αἰών. Therefore, the source of the flow of liquids indicates a core of deep vitality.

ἄρδοντι καλλίστᾳ δρόσῳ,

They refresh the clan of the Psalychiadai

with the finest dew of the Graces

The Psalychiadai represent the predecessors of the laudandi. ἄρδειν literally means “watering.” The glory (that is, the κλέος) of the ancestors in question is revived by dew, which is metaphorically produced by the multiple victories carried off at the Isthmian and the Nemean games (cf. lines 60–62). [8] Analogously, in Hesiod the Muses assure the king of his glorious life and, potentially, his heroic afterlife by “pouring sweet dew” on him. [9]

Who would not fluently sing Phoebus?

The singing about Apollo is characterized as something fluid; [10] the rhetorical question in this case implies that the “fluency” of such an activity is natural, common, and expected. As a counterpart to this implicit idea, I should like to quote a Pindaric statement that makes the same point all the more explicit.

ὕδατος ὥτε ῥοὰς φίλον ἐς ἄνδρ’ ἄγων

κλέος ἐτήτυμον αἰνέσω· (…)

(…) Keeping away dark blame,

like streams of water I shall bring genuine fame

with my praises to the man who is my friend

The first-person verb αἰνέσω denotes the professional performance of the singing “I,” whose essence is captured by the image of a dynamic transferral of water bringing fame.

δάκρυα θερμὰ χέων ὥς τε κρήνη μελάνυδρος,

ἥ τε κατ’ αἰγίλιπος πέτρης δνοφερὸν χέει ὕδωρ.

Meanwhile Patroklos came to the shepherd of the people, Achilleus,

and stood by him and wept warm tears, like a spring dark-running

that down the face of a rock impassable drips its dim water

Just as water drips from rocks timelessly—note the present χέει “pours,” whose time span is unspecified [14] —so Patroclus’ tears are shed and simultaneously projected to his afterlife. The same type of resonance underlies the elliptical sense of the lines concluding the embedded tale of Niobe (Iliad XXIV 601–620). Lines 614–617 recite: νῦν δέ που ἐν πέτρῃσιν ἐν οὔρεσιν οἰοπόλοισιν / ἐν Σιπύλῳ, (…) / ἔνθα λίθος περ ἐοῦσα θεῶν ἐκ κήδεα πέσσει, which literally means: “And now somewhere in the lonely mountains / in Sipylos (…) / there, even if she is stone thanks to the gods, she makes her sorrows mellow.” [15] The reader may note, once again, the omnitemporal present πέσσει, whose basic meaning, “making mellow,” can be applied to various objects, thus resulting in different smoothing effects. One of them is “to moisten, to wet,” which fits a traditional belief associated with the cliff of Sipylus. Quintus Smyrnaeus (I 293–306) provides the description of a natural phenomenon in Sipylus; that is, a stream falling from the heights of a rugged cliff, which visually suggests the shape of a woman shedding tears: “A great marvel is she to passers by, because she is like a sorrowful woman, who mourns some cruel grief, and weeps without stint. Such verily seems the figure, when thou gazest at it from afar; but when thou drawest near, lo, ‘tis but a sheer rock, a cliff of Sipylus.” [16] The association is famously alluded to also in Sophocles’ Antigone, where Antigone compares herself to Niobe. She gives the following account of Niobe-as-stone:

τὰν Φρυγίαν ξέναν

Ταντάλου Σιπύλῳ πρὸς ἄ-

κρῳ, τὰν κισσὸς ὡς ἀτενὴς

πετραία βλάστα δάμασεν,

καί νιν ὄμβρῳ τακομέναν,

ὡς φάτις ἀνδρῶν,

χιών τ’ οὐδαμὰ λείπει, τέγ-

γει θ’ ὑπ’ ὀφρύσι παγκλαύτοις

δειράδας (…)

Nagy sets forth the paradoxical co-existence of a petrified figure that can perpetually produce fluidity:

As much as the source of Niobe’s tears is inexhaustible, eternally unwilting is the transmission of indelible events, however sad they may be. The flow of tears can be the materialization of the flow of memory. Odysseus weeps as he listens to Demodocus’ songs (Odyssey viii 83–89 and 521–534). By doing so he endorses the unwilting kleos of the epic performance. His own memory starts flowing and ultimately merges with his own performance of further songs. [19] On the feminine side, the tears of wailing women before dead bodies have a very similar power; that is, they make the death and the deeds of heroes flow through the mind and down the body of whoever enacts the memory of them. [20] As Lynch (2005:72) reminds us, “the continuation of mourning discourse after stylized weeping assures the continuation of the deceased’s memory.” [21] Such peculiar kind of communication—ephemeral in its realization, but eternal in its effects—causes pleasure, even delight, as Andromache in Euripides’ Andromache reminds us: “I shall raise up to heaven the mourning and lamentation and tears in which I am enmeshed. For women naturally take delight (τέρψις) in present evils, forever keeping them on their lips and tongues” (lines 91–95). [22]

sunt lacrimae rerum et mentem mortalia tangunt.

solve metus; feret haec aliquam tibi fama salutem.”

“(…) things requiring praise have their own reward.

There are tears that connect with the real world, and things that happen to mortals touch the mind.

Dissolve your fears: this fame will bring for you too a salvation of some kind.”

The “organic” component of tears is what connects mental and sensorial activities. [24] The nourishing component comes both from the narration expressed by the pictorial medium, and from the tears of the reception. [25] Tears are vital liquid, which, as stated earlier, can supply life and afterlife, salvation and fame. Aeneas’ words seem to capture (and reflect) a potential for tears that is part of Greek ritual laments. As Alexiou 1974 has shown, a ritual lament encodes a dialogue in response to death; more than that, such a dialogue is a creative response and, projectively, an artistic one. Ritual tears “transform the suffering of the living into aesthetic creativity” (Lynch 2005:80). [26]

Tears in Dowland’s music

exilde for euer: let mee morne

where nights black bird hir sad infamy sings

there let mee liue forlorne. [32]

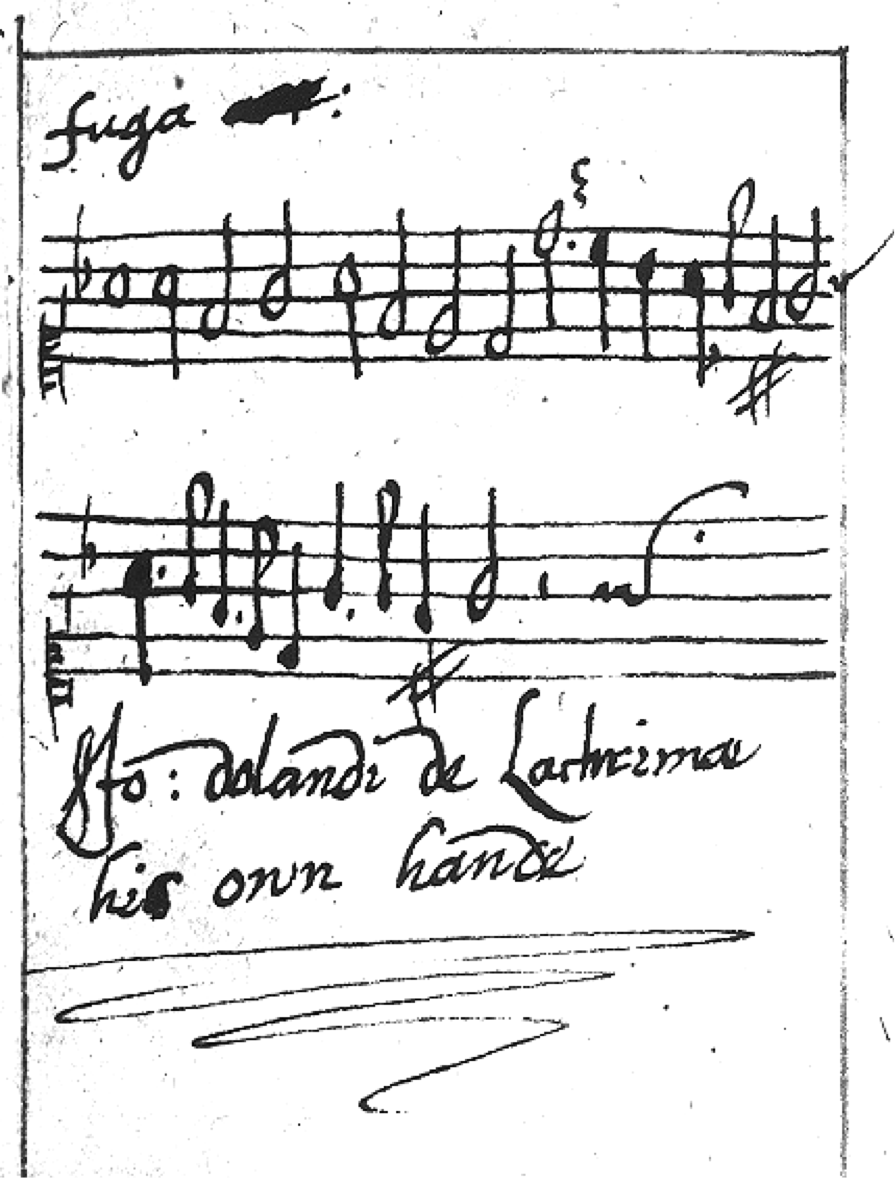

Fig. 1: Opening of song n. 2 from Dowland’s Second Book of Songs (1600); Rooley 1983:6

Fig. 2: Title page of Lachrimae (1604).

And sweetly weep into thy lady’s breast.

And as the dews revive the drooping flow’rs,

So let your drops of pity be address’d,

To quicken up the thoughts of my desert,

Which sleeps too sound whilst I from her depart.

Tears are in motion and can reach others; they can touch and change others; they are evoked together with morning showers and with dew that revive flowers, that is, they restore to life and consciousness; they may animate the desert of one’s mind. In the second verse the singing “I” pleads that his sighs might “dissolve her indurate heart,” the latter revealing “frozen rigour like forgetful Death.” These metaphors resonate with the communicative powers of flowing water I recalled at the beginning of the paper. Drops of tears dissolve the ice of forgetfulness. Fluidity overrides rigor mortis. The hoped-for transformation by tears is simultaneously operated by music, by weeping music.

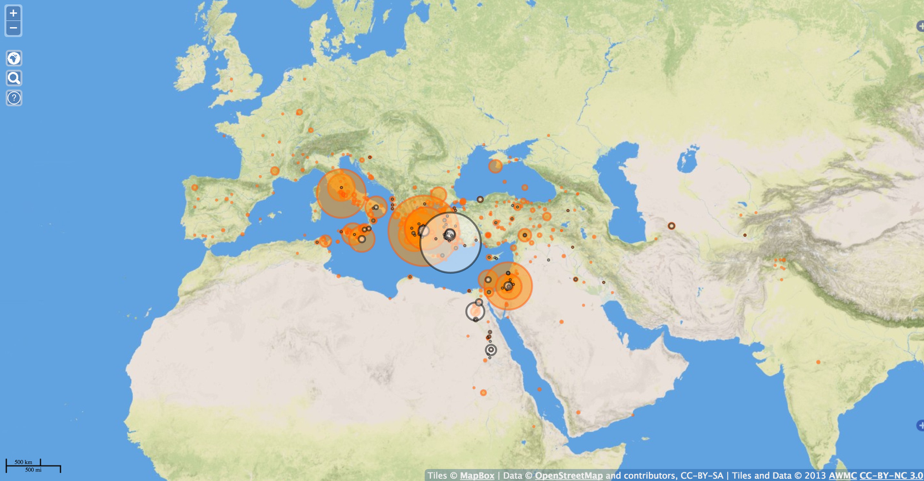

Fig. 3: see: http://www.doc.gold.ac.uk/~mas01tc/web/ECOLMtest/IMSweb/Dow2wd95REV.htm

Conclusion: Performing as weeping

e che sospiri / la libertá.

Il duolo infranga / queste ritorte

de’ miei martiri / sol per pietà.

Let me weep my cruel fate,

and let me sigh for liberty.

May sorrow break these chains

of my sufferings just for the sake of pity.

While Almirena ardently desires to weep over her fate, she does weep an exquisite melody; while she hopes that sorrow will break her chains, the soothing Aria that she performs liberates from any distress all those who hear it. [48] Most certainly the beauty of melancholy may reside in the act of retrieving the beauty of something one has loved and then lost. [49] To this I would add: the beauty contained in songs of tears and weeping may indeed reside in performing the beauty of tears. Dowland’s works were quite conceivably infused with this very idea. They are undeniably infused with such beauty, which—I will now venture to say–is the same profound perception that Nagy discerns in Andromache as, for the last time, she looks at Hector (2009: 186): “It is a world of tears, and there is a world of beauty in these tears.” [50]