“The past is not what has disappeared, it is on the contrary what belongs to us.”

CAPTION: Leda and the Swan

reine sans arène,

tour trouée,

fou à lier,

cavalier seul.

King without a retinue

Queen without a court

Castle breached

Bishop betrayed

Knight all alone. [2]

Leiris’ poem plays on the metaphor of chess as life. The lines describe isolated figures on a chessboard, but the combination of these particular pieces suddenly comes to life. Leiris draws attention to the narrative power of traditional chess elements, and to the ways in which the artist can weave these elements into a human story.

Desplechin also comments, in the filmed interview accompanying the DVD, on his extensive use of quotations, explaining how the film must work regardless of whether people recognize particular allusions. While the story does make sense regardless of one’s knowledge of Yeats, Apollinaire or Homer, the constant references to literature collectively make a more interesting point about the nature of the literary tradition and its role in our lives. Like poetry, film transforms the raw material of daily life into the mythical and magical. We learn late in the film that the title of Louis Jenssens’ last book is Cavalier Seul, another allusion to Leiris’ poem, but we cannot tell at what level the allusion works: is Louis quoting Leiris, or is Desplechin playing with the metaphor of life as a game of chess by having his characters obliviously reenact a game that has been played countless times. The two possibilities are not incompatible since, alongside more self-conscious allusions, Desplechin also highlights repetition as a theme that allows for accidental resemblances. Whether parallels are planned or unintentional, the effect is the same in creating, and stressing the importance of, connections to the literary tradition.

I’m crossing you in style some day.

Oh, dream maker, you heart breaker,

wherever you’re going I’m going your way.

Two drifters off to see the world.

There’s such a lot of world to see.

We’re after the same rainbow’s end—

waiting ’round the bend,

my huckleberry friend,

Moon River and me. [4]

The song was composed for the 1961 film Breakfast at Tiffany’s. In a memorable scene Holly Golightly (played by Audrey Hepburn), perched on the fire escape of her New York apartment, sings the song while accompanying herself on the guitar. The music thus evokes the earlier film’s heroine, a woman who, like Nora, refuses to define herself by the tragic events of her life and who fashions herself as a queen who will, some day, cross the river “in style.” [5] The lyrics also indirectly evoke two famous literary wanderers, Huck and Jim from Mark Twain’s Huckleberry Finn. The river itself represents Holly Golightly’s hopes and dreams for her life, but also her awareness of its risks, and the potential for disappointment and loss. Dreams lead to heartbreak, but together they can provide the inspiration to transform the everyday into song.

CAPTION: Nora (Emanuelle Devos) tells her life story

CAPTION: Ismael (Mathieu Amalric) recounts his dream

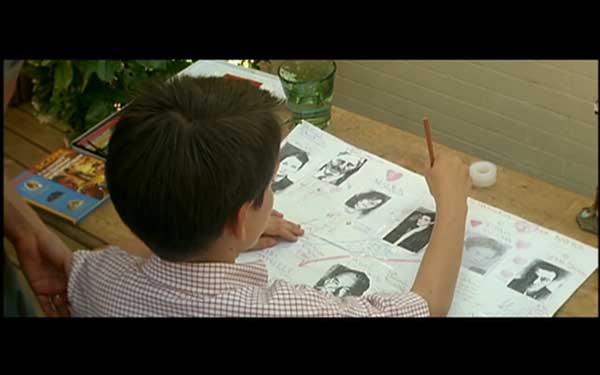

CAPTION: Elias’ genealogical tree