Web producer: Noel Spencer

Consultant for images: Jill Curry Robbins

| Iliad | Rhapsody 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15, 16, 17, 18, 19, 20, 21, 22, 23, 24 |

| Odyssey | Rhapsody 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15, 16, 17, 18, 19, 20, 21, 22, 23, 24 |

| readable even for first-timers |

| readable, but not necessarily the first time around |

| readable, but only by those who might be interested |

| readable mostly for specialists, or in general for those who are very interested in a given topic |

Iliad Rhapsody 1

2016.06.09 / enhanced 2018.08.16

Figure 1. “The Rage of Achilles,” by Giovanni Battista Tiepolo, 1757, [public domain], via Wikimedia Commons.

Figure 1. “The Rage of Achilles,” by Giovanni Battista Tiepolo, 1757, [public domain], via Wikimedia Commons.I.01.001–012

I.01.001–002

I.01.001

I.01.001

I.01.002

I.01.002

I.01.002

I.01.003–005

I.01.005

I.01.008–012

I.01.015

I.01.028

I.01.052

I.01.069

I.01.074–083

I.01.075

I.01.086

I.01.091

I.01.096–098

I.01.097

I.01.110

I.01.122

I.01.153

I.01.155

I.01.159

I.01.177

I.01.188

I.01.197

I.01.207

I.01.225

I.01.231

I.01.233–246

I.01.233–237

I.01.244

I.01.247

I.01.282

I.01.291

I.01.320–348

I.01.321

I.01.335

I.01.337

I.01.341

I.01.345

I.01.350–359

I.01.362

I.01.365–392

I.01.396–406

I.01.403–404

I.01.407–412

I.01.412

I.01.416

I.01.418

I.01.423–425

I.01.454

I.01.456

I.01.463

I.01.463

I.01.468

I.01.473

I.01.477

I.01.503–510

I.01.509

I.01.524–530

I.01.528–530

I.01.558–559

I.01.602

I.01.603–604

Iliad Rhapsody 2

2016.07.01 / enhanced 2018.08.16

Figure 2. Inscription on the reverse side of the coin: ΘΗΒΑΙΩΝ. Pictured: the Greek hero Protesilaos, the first Achaean to step on Trojan soil and, according to the myth, the first to die in the Trojan War. The myth is retold in Iliad 2.695–709.

Figure 2. Inscription on the reverse side of the coin: ΘΗΒΑΙΩΝ. Pictured: the Greek hero Protesilaos, the first Achaean to step on Trojan soil and, according to the myth, the first to die in the Trojan War. The myth is retold in Iliad 2.695–709.I.02.001–006

I.02.007–015

I.02.026

I.02.029–030

I.02.036–040

I.02.041

I.02.046

I.02.063

I.02.082

I.02.086

I.02.094

I.02.100–108

I.02.101

I.02.108

I.02.110

I.02.119–130

I.02.186

I.02.212

I.02.214

I.02.216

I.02.217–219

I.02.221

I.02.222

I.02.224

I.02.225–242

I.02.235

I.02.241–242

I.02.243

I.02.245

I.02.246–264

I.02.246

I.02.247

I.02.248–249

I.02.251

I.02.255

I.02.256

I.02.265–268

I.02.268

I.02.269–270

I.02.275

I.02.277

I.02.299–332

I.02.299–310

I.02.308

I.02.318

I.02.319

I.02.325

I.02.330

I.02.401

I.02.402–429

I.02.402–429

I.02.408–409

I.02.408

I.02.431

I.02.484–487

I.02.484

I.02.486

I.02.488–493

I.02.492

I.02.493

I.02.540

I.02.546–552

I.02.546

I.02.547–548

I.02.548

I.02.553–554

I.02.557–568

I.02.557–558

I.02.577

I.02.580

I.02.594–600

I.02.637

I.02.653–670

I.02.655–656

I.02.658

I.02.663

I.02.666

I.02.668

I.02.681–694

I.02.689–694

I.02.689–694

I.02.695–709

I.02.704

I.02.745

I.02.760–770

I.02.761

“The Muse Calliope” (about 1730). Charles-Antoine Coypel (1694–1752). Image via Wikimedia Commons.

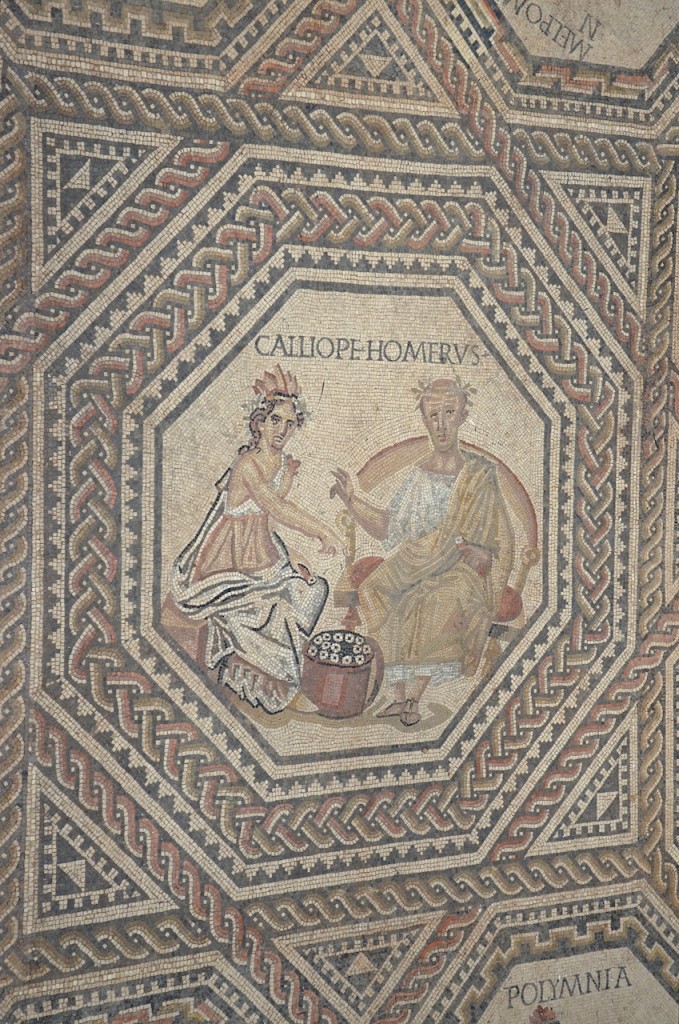

“The Muse Calliope” (about 1730). Charles-Antoine Coypel (1694–1752). Image via Wikimedia Commons. Central medallion of the Vichten mosaic (about 240 CE). National Museum of History and Art, Luxembourg. Image via Flickr, under a CC BY-SA 2.0 license.

Central medallion of the Vichten mosaic (about 240 CE). National Museum of History and Art, Luxembourg. Image via Flickr, under a CC BY-SA 2.0 license.I.02.761

“Calliope” (1869). Giuseppe Fagnani (1819–1873). Image via Wikimedia Commons.

“Calliope” (1869). Giuseppe Fagnani (1819–1873). Image via Wikimedia Commons.

The medium for the reading of Homer here is imagined as a codex, not as a scroll: compounding of anachronisms.

“Calliope, Muse of Epic Poetry” (1620). Giovanni Baglione (1566–1643). Image via Wikimedia Commons.

“Calliope, Muse of Epic Poetry” (1620). Giovanni Baglione (1566–1643). Image via Wikimedia Commons.I.02.811–815

I.02.829

I.02.831–832

I.02.835

I.02.842

I.02.867–869

Iliad Rhapsody 3

2016.07.07 / enhanced 2018.08.16

Figure 3. Menelaos pulling Paris by the helmet. Detail of Roman sarcophagus of Aurelia Botania Demetria (2nd c. CE); Antalya Archaeological Museum. Image via Wikimedia Commons.

Figure 3. Menelaos pulling Paris by the helmet. Detail of Roman sarcophagus of Aurelia Botania Demetria (2nd c. CE); Antalya Archaeological Museum. Image via Wikimedia Commons.I.03.038

I.03.059

I.03.100

I.03.125–128

I.03.126

I.03.147

I.03.164

I.03.237

I.03.242

I.03.284

I.03.374

Iliad Rhapsody 4

2016.07.21 / enhanced 2018.09.08

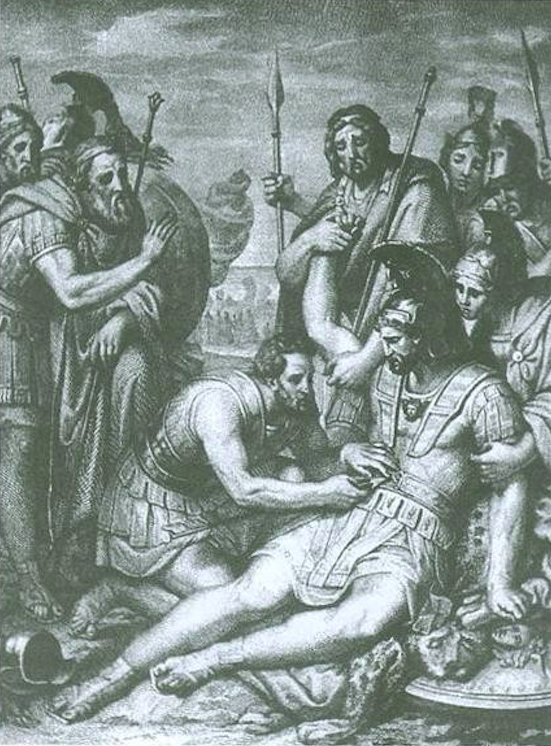

Figure 4. The healer Makhaon attends to the wounded Menelaos. Engraving by Francesco Nenci for an edition of the Iliad published in 1838.

Figure 4. The healer Makhaon attends to the wounded Menelaos. Engraving by Francesco Nenci for an edition of the Iliad published in 1838.I.04.048

I.04.110

I.04.118–121

I.04.128

I.04.178-179

I.04.183

I.04.196

I.04.197

I.04.227

I.04.241

I.04.242

I.04.313–314

I.04.327–328

I.04.368–410

I.04.386

I.04.389

I.04.513

Iliad Rhapsody 5

2016.07.28 / enhanced 2018.09.08

Figure 5a. “Aeneas and Diomedes.” Wenceslaus Hollar (Bohemian, 1607–1677). Image via Wikimedia Commons.

Figure 5a. “Aeneas and Diomedes.” Wenceslaus Hollar (Bohemian, 1607–1677). Image via Wikimedia Commons.I.05.048

I.05.059–064

I.05.059–061

I.05.063

I.05.077–078

I.05.077–078

I.05.083

I.05.103

I.05.173

I.05.231

I.05.263–273

I.05.269

I.05.296

I.05.312

I.05.369

I.05.370–371

I.05.395–404

I.05.401

I.05.406–415

I.05.430

I.05.432–444

Figure 5b. “The Combat of Diomedes” (1776). Jacques-Louis David (French, 1748–1825). Image via Wikimedia Commons.

Figure 5b. “The Combat of Diomedes” (1776). Jacques-Louis David (French, 1748–1825). Image via Wikimedia Commons.I.05.438

I.05.440–442

I.05.441–442

I.05.441

I.05.459

I.05.473–474

I.05.500

I.05.541

I.05.571

I.05.580

I.05.638

I.05.639

I.05.646

I.05.669

I.05.696–698

I.05.710

I.05.722

I.05.733–747

I.05.734–735

I.05.795

I.05.839

I.05.843

I.05.891

I.05.899

Iliad Rhapsody 6

2016.08.04 / enhanced 2018.09.08

Figure 6. Apulian red-figure column-crater (ca. 370–360 BCE) depicting an intimate family scene: Hector removes his helmet as he says his final farewell to his wife Andromache and to their child Astyanax. Public domain image by Jastrow via Wikimieda Commons.

Figure 6. Apulian red-figure column-crater (ca. 370–360 BCE) depicting an intimate family scene: Hector removes his helmet as he says his final farewell to his wife Andromache and to their child Astyanax. Public domain image by Jastrow via Wikimieda Commons.I.06.018

I.06.053

I.06.067

I.06.090–093

I.06.119–149

I.06.271–273

I.06.209

I.06.211

I.06.286–311

I.06.286–296

I.06.289–292

I.06.294

I.06.297–310

I.06.325

I.06.333

I.06.402–403

I.06.407–439

I.06.407–439

I.06.447–464

I.06.466–470

I.06.484

I.06.494–496

Iliad Rhapsody 7

2016.08.12 / enhanced 2018.09.08

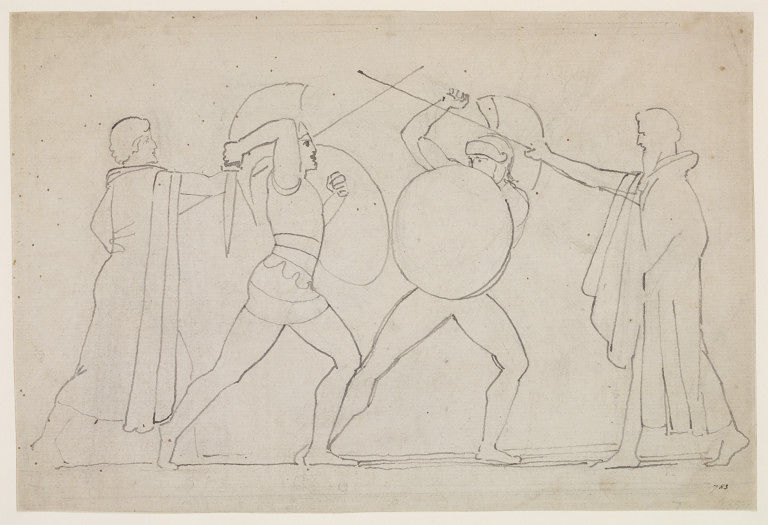

Figure 7. Hector and Ajax separated by heralds, pen and ink drawing by John Flaxman, 1790’s. Image via Victoria and Albert Museum.

Figure 7. Hector and Ajax separated by heralds, pen and ink drawing by John Flaxman, 1790’s. Image via Victoria and Albert Museum.I.07.015–017

I.07.015–017

I.07.017–061

I.07.021

I.07.063–064

I.07.067–091

I.07.084–086

I.07.089–090

I.07.090

I.07.092–169

I.07.095

I.07.122

I.07.123–161

I.07.132–157

I.07.147

I.07.149

I.07.161

I.07.177–180

I.07.197–198

I.07.203

I.07.228

I.07.288–289

I.07.298

I.07.319–322

I.07.324

I.07.336–343

I.07.382

I.07.421–423

I.07.433–465

Iliad Rhapsody 8

2016.08.18 / enhanced 2018.09.08

Figure 8. “Hera, Athena, and Iris in the Trojan War,” Jacques Réattu (1760–1833). Image via Wikimedia Commons.

Figure 8. “Hera, Athena, and Iris in the Trojan War,” Jacques Réattu (1760–1833). Image via Wikimedia Commons.I.08.002

I.08.002

I.08.066–077

I.08.078–117

I.08.078–117

I.08.079

I.08.104

I.08.107

I.08.113–114

I.08.119

I.08.123

I.08.130–171

I.08.170–171

I.08.175–176

I.08.180–183

I.08.185

I.08.215

I.08.220–227

I.08.228–235

I.08.315

I.08.339

I.08.363

I.08.367

I.08.379–380

I.08.485–486

I.08.526–541

l.08.526

I.08.538–541

Iliad Rhapsody 9

2016.08.26 / enhanced 2018.09.08

Figure 9. The embassy to Achilles, featuring Phoenix and Odysseus in front of Achilles. Attic red-figure hydra, circa 480 BCE. Public domain image via Wikimedia Commons.

Figure 9. The embassy to Achilles, featuring Phoenix and Odysseus in front of Achilles. Attic red-figure hydra, circa 480 BCE. Public domain image via Wikimedia Commons.I.09.001–003

I.09.002

I.09.003

I.09.004–008

I.09.004

I.09.008–009

I.09.057–058

I.09.076–077

I.09.097–099

I.09.104–108

I.09.115–120

I.09.120–161

I.09.128–131 / I.09.270–272

I.09.128–131 / I.09.270–272

I.09.130

I.09.158–161

I.09.167–170

I.09.179–181

I.09.182–198

I.09.185–191

I.09.193–198

I.09.223

I.09.225–306

I.09.225–228

I.09.229

I.09.236

I.09.241–243

I.09.249–250

I.09.260

I.09.260–299

I.09.270–272

I.09.307–430

I.09.308–311

I.09.312–313

I.09.314–429

I.09.328–333

I.09.328–333

I.09.340–343

I.09.346–352

I.09.359–363

I.09.360

I.09.404–405

I.09.410–416

I.09.413

I.09.421–422

I.09.434–605

I.09.435–436

I.09.502–512

I.09.522

I.09.524–599

I.09.561–564

I.09.590–594

I.09.602

I.09.606–619

I.09.617–618

I.09.624–642

I.09.628–638

I.09.642

I.09.643–655

I.09.650–653

I.09.656–657

I.09.664–668

I.09.674

Iliad Rhapsody 10

2016.09.14 / enhanced 2018.09.11

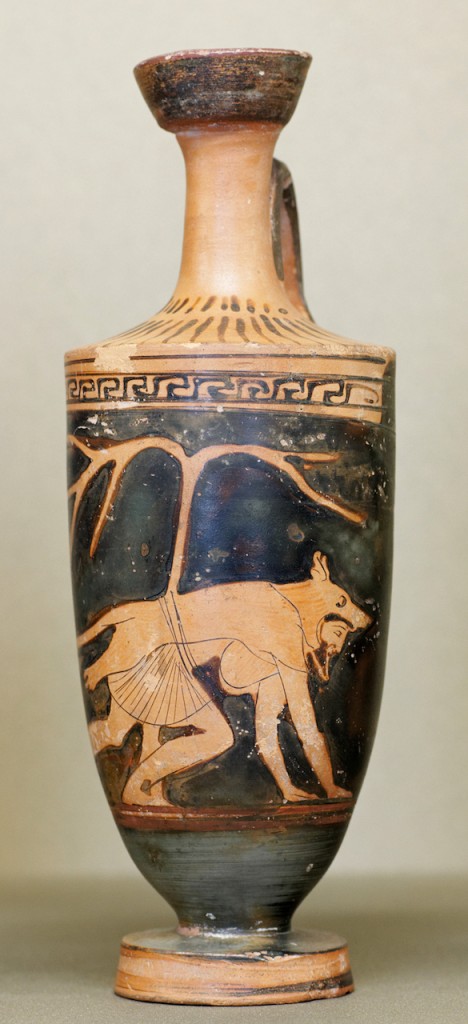

Figure 10. Dolon. Detail from an Attic red-figure lekythos (460 BCE). Image via Wikimedia Commons.

Figure 10. Dolon. Detail from an Attic red-figure lekythos (460 BCE). Image via Wikimedia Commons.I.10.000

I.10.032–033

I.10.043–052

I.10.212–213

I.10.213

I.10.224–226

I.10.227–232

I.10.228

I.10.233–240

I.10.241–247

I.10.249–253

I.10.316

I.10.329

I.10.415

I.10.437

I.10.437

I.10.482

Iliad Rhapsody 11

2016.09.22 / enhanced 2018.09.11

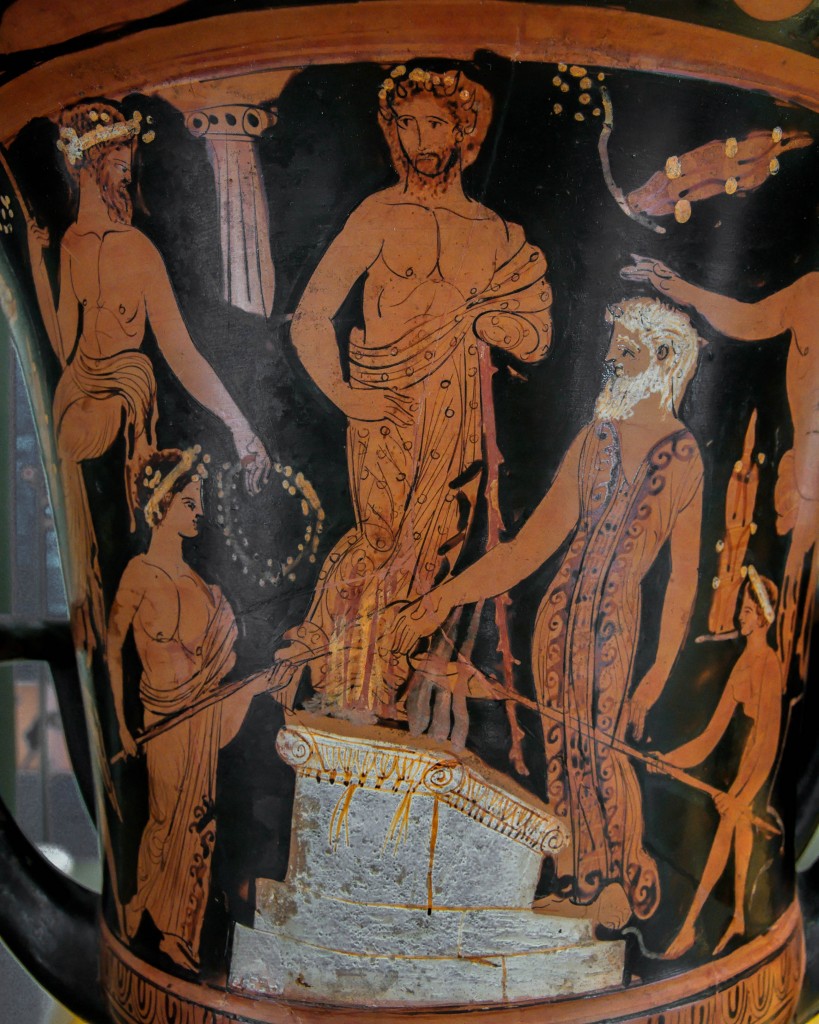

Figure 11. Nestor and his sons sacrifice to Poseidon. Attic red-figure calyx-krater, ca. 400–380 BCE. © Marie-Lan Nguyen / Wikimedia Commons, via Wikimedia Commons.

Figure 11. Nestor and his sons sacrifice to Poseidon. Attic red-figure calyx-krater, ca. 400–380 BCE. © Marie-Lan Nguyen / Wikimedia Commons, via Wikimedia Commons.I.11.001–002

I.11.005–016

I.11.032–040

I.11.041

I.11.058

I.11.078–079

I.11.104–112

I.11.200

I.11.218–231

I.11.218

I.11.227

I.11.288

I.11.295

I.11.297-298

I.11.297

I.11.317–319

I.11.322

I.11.347

I.11.488

I.11.497–500

I.11.506

I.11.508

I.11.564

I.11.599-600

I.11.604

I.11.620

I.11.624–627

I.11.624–627

I.11.627

I.11.664–667

I.11.668

I.11.670

I.11.699–702

I.11.671-761

I.11.690

I.11.735

I.11.784

I.11.787

I.11.806–808

I.11.818

I.11.832

I.11.843

Iliad Rhapsody 12

2016.09.28 / enhanced 2018.09.11

Figure 12. “Siege of the Greek Camp.” Crispijn van de Passe (I) (1613). Public domain image, via Rijks Museum.

Figure 12. “Siege of the Greek Camp.” Crispijn van de Passe (I) (1613). Public domain image, via Rijks Museum.I.12.002–033

I.12.015

I.12.018

I.12.023

I.12.070

I.12.076

I.12.090

I.12.111

I.12.118–123

I.12.130

I.12.159

I.12.188

I.12.198

I.12.228

I.12.235–236

I.12.252

I.12.255–257

I.12.270

I.12.310–321

I.12.319

I.12.322–328

I.12.331–377

I.12.335–336

I.12.387–391

I.12.400

I.12.436–441

Iliad Rhapsody 13

2016.10.13 / enhanced 2018.09.11

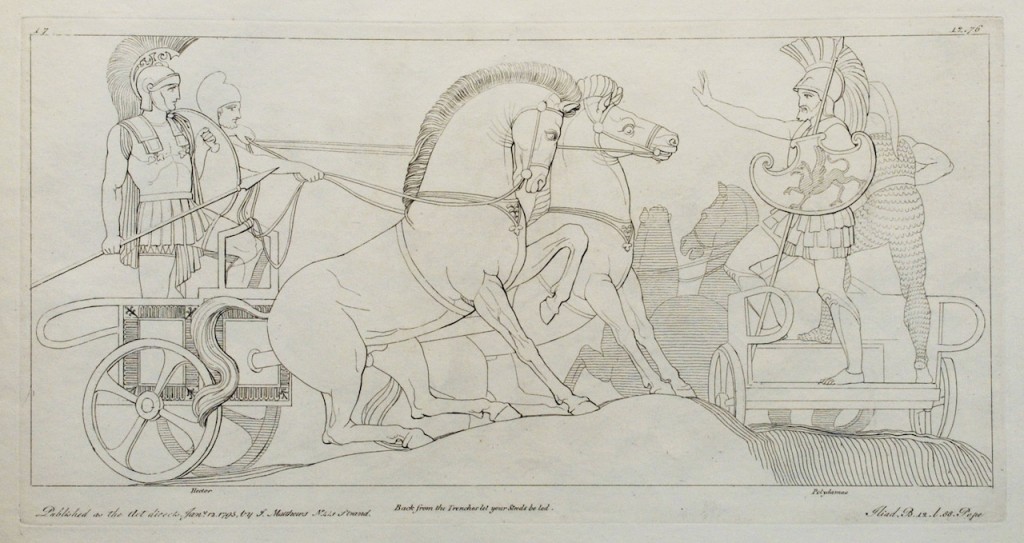

Figure 13. Hector and Polydamas. After a drawing by John Flaxman. Image via Wikimedia Commons.

Figure 13. Hector and Polydamas. After a drawing by John Flaxman. Image via Wikimedia Commons.I.13.023–031

I.13.046–047

I.13.054

I.13.066

I.13.084

I.13.111–113

I.13.197

I.13.201

I.13.202–204

I.13.216–218

I.13.227

I.13.242–244

I.13.244

I.13.246

I.13.313–314

I.13.331

I.13.347

I.13.386

I.13.402–423

I.13.435

I.13.444

I.13.459–461

I.13.600

I.13.628–629

I.13.631–639

I.13.659

I.13.681

I.13.685

I.13.688

I.13.689–691

I.13.700

I.13.726–735

I.13.737–739

I.13.795–799

I.13.802

I.13.825–829

I.13.831–832

Iliad Rhapsody 14

2016.10.19 / enhanced 2018.09.11

Figure 14. Juno and Jupiter. Detail from “Loves of the Gods,” fresco by Annibale Carracci (1560–1609). Annibale Carracci [Public domain], Image via Wikimedia Commons.

Figure 14. Juno and Jupiter. Detail from “Loves of the Gods,” fresco by Annibale Carracci (1560–1609). Annibale Carracci [Public domain], Image via Wikimedia Commons.I.14.027–036

I.14.070

I.14.187

I.14.200–210

I.14.201

I.14.238–240

I.14.245–246–246a

I.14.246a ἀνδράσιν ἠδὲ θεοῖς, πλείστην <τ᾿> ἐπὶ γαῖαν ἵησιν

Taken together, these verses can be translated this way:

I.14.246a men and gods, and he flows over the Earth in all her fullness.

I.14.270–280

I.14.282–293

I.14.301–302

I.14.436

I.14.483

I.14.508

Iliad Rhapsody 15

2016.10.27 / enhanced 2018.09.11

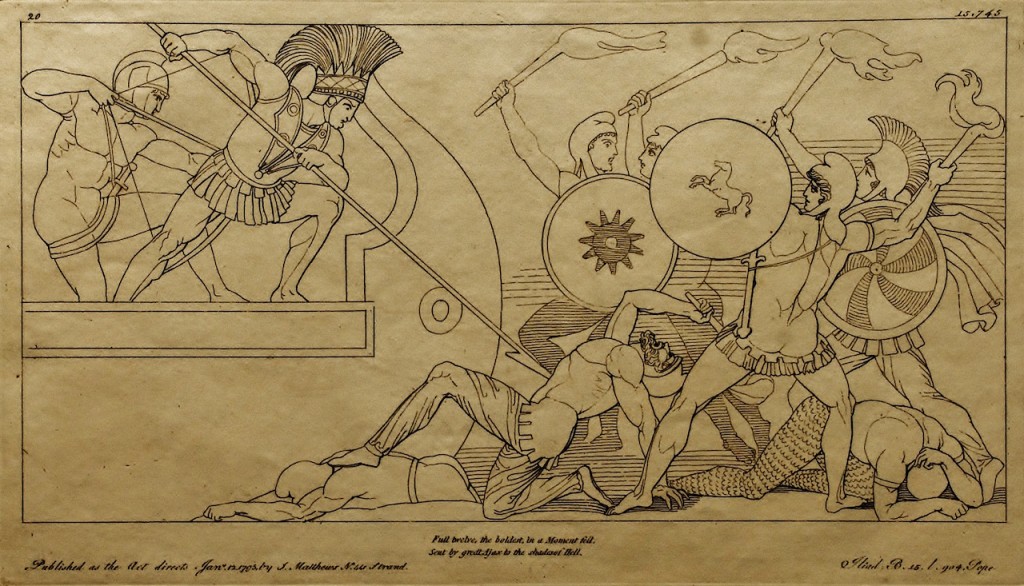

Figure 15. Ajax defending the ships of the Greeks. After a drawing by John Flaxman. Image via Wikimedia Commons.

Figure 15. Ajax defending the ships of the Greeks. After a drawing by John Flaxman. Image via Wikimedia Commons.I.15.037–038

I.15.059–060

I.15.056–077

I.15.064–071

I.15.069–071

I.15.189

I.15.233

I.15.262

I.15.309–310

I.15.383

I.15.385

I.15.401

I.15.405–407

I.15.414–421

I.15.428

I.15.431

I.15.494–499

I.15.564

I.15.585

I.15.592–602

I.15.640

I.15.696–746

I.15.704-746

I.15.733

Iliad Rhapsody 16

2016.11.09 / enhanced 2018.09.11

Figure 16. A chariot driver and a chariot fighter in a biga (two-horses chariot). Terracotta, Late Helladic IIIA–IIIB (ca. 1400–1200 BCE). Louvre Museum, CA 2959. Credit line: Purchase, 1934. Image Marie-Lan Nguyen (User:Jastrow), 2009-06-28 [CC BY 2.5], via Wikimedia Commons.

Figure 16. A chariot driver and a chariot fighter in a biga (two-horses chariot). Terracotta, Late Helladic IIIA–IIIB (ca. 1400–1200 BCE). Louvre Museum, CA 2959. Credit line: Purchase, 1934. Image Marie-Lan Nguyen (User:Jastrow), 2009-06-28 [CC BY 2.5], via Wikimedia Commons.I.16.021

I.16.022

I.16.032

I.16.052

I.16.055

I.16.057

I.16.075

I.16.080

I.16.087–096

I.16.097–100

I.16.112

I.16.113

I.16.119–121

I.16.122–124

I.16.140–144

I.16.149

I.16.150–151

I.16.165

I.16.189

I.16.213

I.16.235

I.16.237

I.16.240–248

I.16.244

I.16.255-256

I.16.271–272

I.16.272

I.16.273–274

I.16.279

I.16.282

I.16.286

I.16.293/301

I.16.294–298

I.16.301

I.16.362

I.16.364–366

I.16.383–393

I.16.437

I.16.440–457

I.16.454–455

I.16.455

I.16.456–457

I.16.464

I.16.514

I.16.548–553

I.16.605

I.16.653

I.16.670

I.16.671–673

I.16.673

I.16.674–675

I.16.680

I.16.682

I.16.683

I.16.685–687

I.16.705–711

I.16.722–723

I.16.767

I.16.784

I.16.786–804

I.16.787

I.16.804–806

I.16.815

I.16.844–845

I.16.856

I.16.865

Iliad Rhapsody 17

2016.11.18 / enhanced 2018.09.20

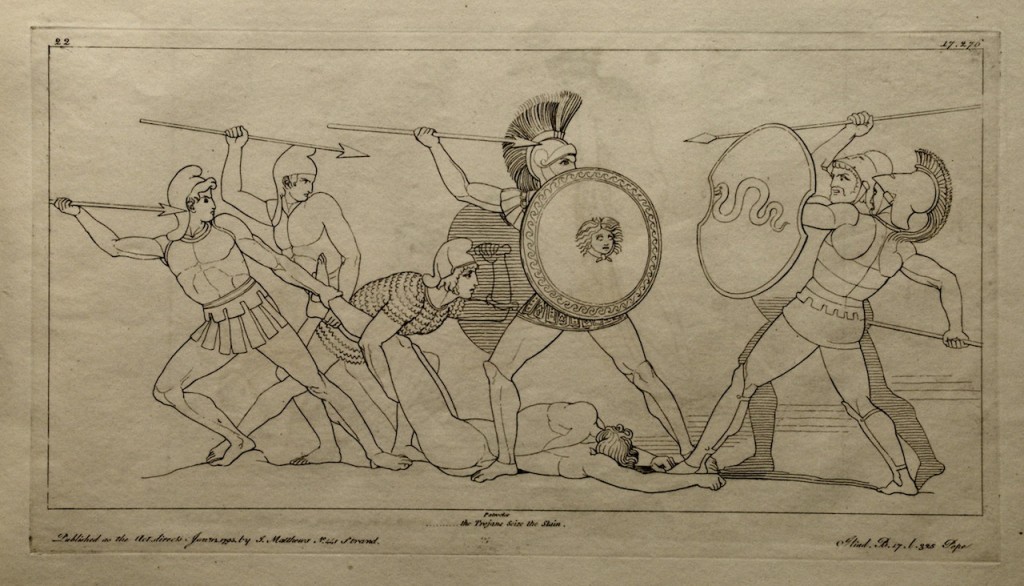

Figure 17. Copperplate etching (1795) by Tommaso Piroli, after a drawing (1793) by John Flaxman. Photographed/scanned by H.-P.Haack (Antiquariat Dr. Haack Leipzig) [CC BY 3.0 or Public domain]. Image via Wikimedia Commons.

Figure 17. Copperplate etching (1795) by Tommaso Piroli, after a drawing (1793) by John Flaxman. Photographed/scanned by H.-P.Haack (Antiquariat Dr. Haack Leipzig) [CC BY 3.0 or Public domain]. Image via Wikimedia Commons.I.17.050–060

I.17.051–052

I.17.053–060

I.17.072

I.17.088

I.17.098–101

I.17.164

I.17.165

I.17.176–178

I.17.187

I.17.194–214

I.17.194–197

I.17.194

I.17.211

I.17.213-214

I.17.271

I.17.279–280

I.17.319–322

I.17.331–332

I.17.388

I.17.411

I.17.432

I.17.456

I.17.474–483

I.17.547–549

I.17.565

I.17.627

I.17.655

I.17.685–690

I.17.736–741

Iliad Rhapsody 18

2016.11.25 / enhanced 2018.09.20

Figure 18. “The Shield of Achilles.” Illustration originally published in The Penny Magazine of the Society for the Diffusion of Useful Knowledge, September 22, 1832.

Figure 18. “The Shield of Achilles.” Illustration originally published in The Penny Magazine of the Society for the Diffusion of Useful Knowledge, September 22, 1832.I.18.009–011

I.18.015–073

I.18.051–060

I.18.070–071

I.18.073

I.18.074–077

I.18.076

I.18.080–082

I.18.082–085

I.18.095–099

I.18.102–103

I.18.121

I.18.150

I.18.152

I.18.205–206

I.18.214

I.18.225–226

I.18.242

I.18.243–314

I.18.354–356

I.18.369–371

I.18.399

I.18.464–466

I.18.468–613

I.18.478–609

I.18.479–480

I.18.483–608

I.18.482–489

I.18.487–489

I.18.490–491

I.18.491–508

I.18.492

I.18.497–508

I.18.499

I.18.509–515

I.18.515–519

I.18.519

I.18.567–572

I.18.587–589

I.18.590–606

I.18.590

I.18.603–604–(605–)606

Iliad Rhapsody 19

2016.12.01 / enhanced 2018.09.20

Figure 19. Herakles at the tree of the Hesperides, holding three of the golden apples in his left hand. Behind him is the apple tree with the guardian serpent clinging around it. Bronze, 104.5cm (Roman, 1st century C.E.). Image via The British Museum.

Figure 19. Herakles at the tree of the Hesperides, holding three of the golden apples in his left hand. Behind him is the apple tree with the guardian serpent clinging around it. Bronze, 104.5cm (Roman, 1st century C.E.). Image via The British Museum.I.19.001–002

I.19.003–017

I.19.015–017

I.19.031

I.19.044

I.19.047

I.19.056–073

I.19.058–060

I.19.074-075

I.19.076–138

I.19.076–082

I.19.078

I.19.083

I.19.084–085

I.19.085–086

I.19.086–088

I.19.088

I.19.091

I.19.095–133

I.19.098

I.19.105

I.19.111

I.19.134–138

I.19.143

I.19.155

I.19.179–180

I.19.186

I.19.199–214

I.19.216–237

I.19.216

I.19.224

I.19.245–246

I.19.268–281

I.19.268–275

I.19.275

I.19.282–302

I.19.284

I.19.302

I.19.303–308/312–313/314–321

I.19.322–323

I.19.314–338

I.19.327

I.19.329–330, 337

I.19.368–391

I.19.373–380

I.19.404–418

Iliad Rhapsody 20

2016.12.09 / enhanced 2018.09.20

Figure 20. “Venus preventing her son Aeneas from killing Helen of Troy,” Luca Ferrari, circa 1650. Luca Ferrari [Public domain], image via Wikimedia Commons.

Figure 20. “Venus preventing her son Aeneas from killing Helen of Troy,” Luca Ferrari, circa 1650. Luca Ferrari [Public domain], image via Wikimedia Commons.I.20.001–074

I.20.089–102

I.20.178–198

I.20.187–194

I.20.189

I.20.200–258

I.20.209

I.20.209

I.20.213–214

I.20.215–219

I.20.230–241

I.20.238

I.20.241

I.20.244–256

I.20.248–250

I.20.290–352

I.20.302–308

I.20.302–308

I.20.350

I.20.403–405

I.20.487

Iliad Rhapsody 21

2016.12.15 / enhanced 2018.09.20

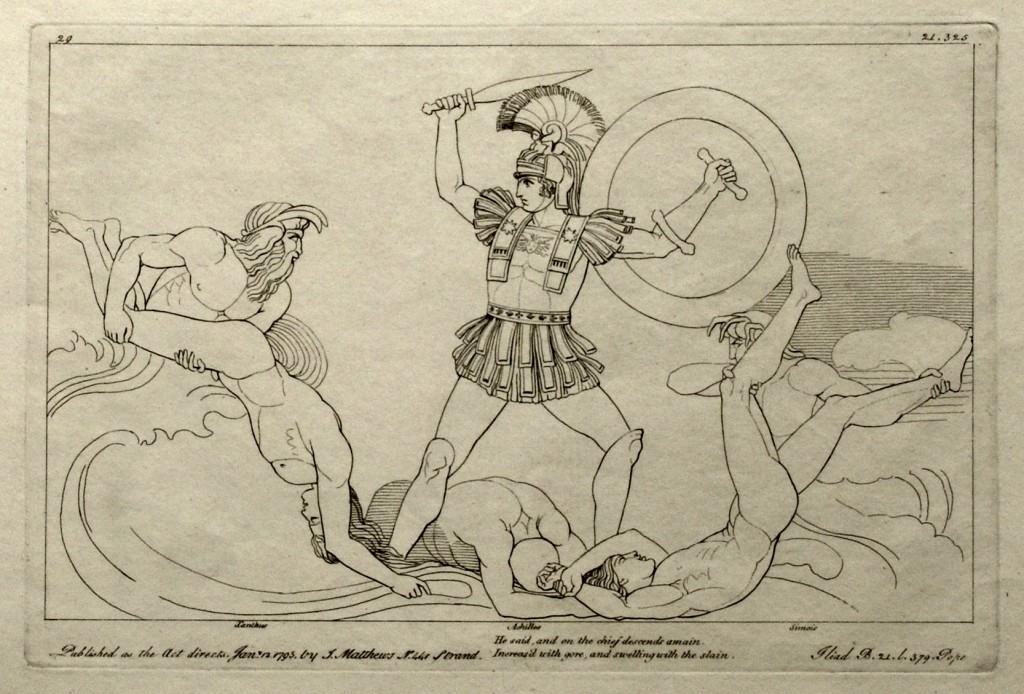

Figure 21. Copperplate etching (1795) by Tommaso Piroli, after a drawing (1793) by John Flaxman. Image via Wikimedia Commons.

Figure 21. Copperplate etching (1795) by Tommaso Piroli, after a drawing (1793) by John Flaxman. Image via Wikimedia Commons.I.21.001–021

I.21.134–135

I.21.184–199

I.21.194–197

I.21.200–327

I.21.328–384

I.21.385–514

Iliad Rhapsody 22

2016.12.24 / enhanced 2018.09.20

Figure 22. Copperplate etching (1795) by Tommaso Piroli, after a drawing (1793) by John Flaxman. Image via Wikimedia Commons.

Figure 22. Copperplate etching (1795) by Tommaso Piroli, after a drawing (1793) by John Flaxman. Image via Wikimedia Commons.I.22.110

I.22.122–130

I.22.297–305

I.22.304

I.22.335–354

I.22.346–348

I.22.368–375

I.22.395–405

I.22.437–475

I.22.440–441

I.22.441

I.22.444

I.22.460–474

I.22.476–515

1.22.483

I.22.500

I.22.506–507

I.22.514

I.22.515

Iliad Rhapsody 23

2016.12.30 / enhanced 2018.09.20

Figure 23. Achilles dragging the body of Hector. Copperplate etching (1795) by Tommaso Piroli, after a drawing (1793) by John Flaxman. Image via Wikimedia Commons.

Figure 23. Achilles dragging the body of Hector. Copperplate etching (1795) by Tommaso Piroli, after a drawing (1793) by John Flaxman. Image via Wikimedia Commons.I.23.001–064

I.23.012

I.23.016

I.23.017

I.23.045

I.23.046–047

I.23.065–092

I.23.071–076

I.23.090

I.23.093–098

I.23.099–107

I.23.108–126

I.23.113

I.23.124

I.23.125–126

I.23.127–137

I.23.138–153

I.23.154–162

I.23.163–183

I.23.184–191

I.23.245–248 … 256–257

I.23.257–258

I.23.326–343

I.23.528

I.23.841

I.23.860

I.23.888

Iliad Rhapsody 24

2016.12.31 / enhanced 2018.09.20

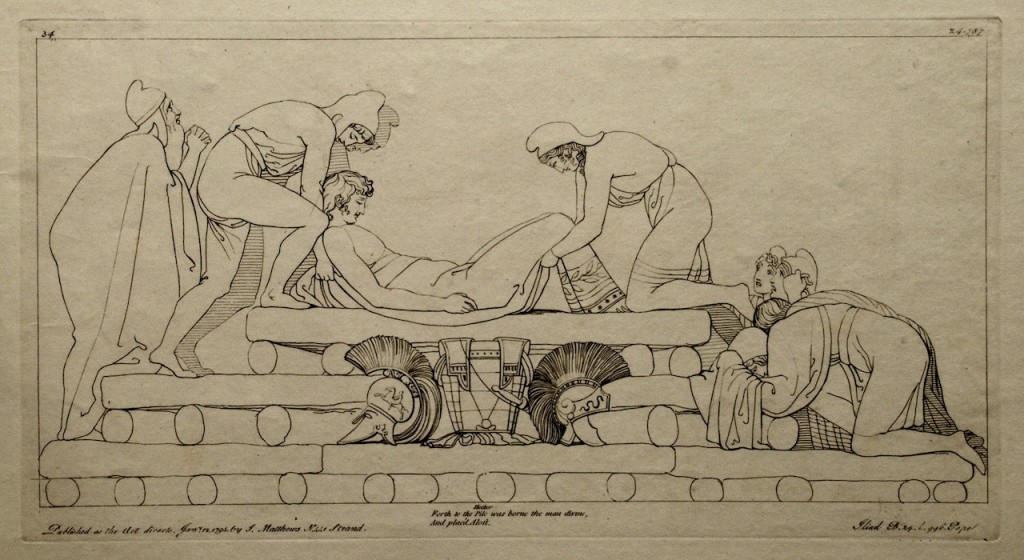

Figure 24. Mourners lament as Hector’s corpse is laid out in preparation for the funeral that closes Iliad Rhapsody 24. Copperplate etching (1795) by Tommaso Piroli, after a drawing (1793) by John Flaxman. Image via Wikimedia Commons.

Figure 24. Mourners lament as Hector’s corpse is laid out in preparation for the funeral that closes Iliad Rhapsody 24. Copperplate etching (1795) by Tommaso Piroli, after a drawing (1793) by John Flaxman. Image via Wikimedia Commons.I.24.001

I.24.006

I.24.014–018

I.24.018–022

I.24.023–28

I.24.029–30

I.24.032–054

I.24.055–063

I.24.064–076

I.24.105

I.24.112–116

I.24.133–137

I.24.158

I.24.187

I.24.396

I.24.406

I.24.438

I.24.474

I.24.509–512

I.24.573

I.24.707–776

I.24.708

I.24.720–776

I.24.723–746

I.24.747–760

I.24.761–776

I.24.777–784

I.24.785–804

[[GN 2016.12.30.]]

Epilogue 1: Hector as the ultimate beau mort

Epilogue 2: Hector as an ideal for Athenians

Odyssey Rhapsody 1

2017.03.02 / enhanced 2018.10.06

O.01.001–010

O.01.001–004

O.01.001

O.01.001–002

O.01.002

O.01.003

O.01.004

O.01.005

O.01.007

O.01.008

O.01.010

O.01.022–026

O.01.032–034

O.01.088–095

O.01.088–089

O.01.093

‘I [= Athena] will conduct [pempein]him [= Telemachus] on his way to Sparta and to sandy Pylos’

But the text as transmitted by Zenodotus (see again the Inventory) reads:

‘I [= Athena] will conduct [pempein] him [= Telemachus] on his way to Crete and to sandy Pylos’

O.01.103

O.01.105

O.01.153–155

O.01.241

O.01.284–286

κεῖθεν δὲ Σπάρτηνδε παρὰ ξανθὸν Μενέλαον·

ὃς γὰρ δεύτατος ἦλθεν Ἀχαιῶν χαλκοχιτώνων.

‘First you [= Telemachus] go to Pylos and ask radiant Nestor

and then from there to Sparta and to golden-haired Menelaos,

the one who was the last of the Achaeans, wearers of bronze tunics, to come back home.’

But the text as transmitted by Zenodotus (see again the Inventory) reads:

κεῖθεν δ’ ἐς Κρήτην τε παρ’ Ἰδομενῆα ἄνακτα,

ὃς γὰρ δεύτατος ἦλθεν Ἀχαιῶν χαλκοχιτώνων.

‘First go to Pylos …

and then from there to Crete and to king Idomeneus

who was the last of the Achaeans, wearers of bronze tunics, to come back home.’

O.01.299

O.01.320–322

O.01.320

O.01.325–327

O.01.326–327

O.01.338

O.01.340–341

O.01.342

O.01.346–352

O.01.383

Odyssey Rhapsody 2

2017.03.08 / enhanced 2018.10.06

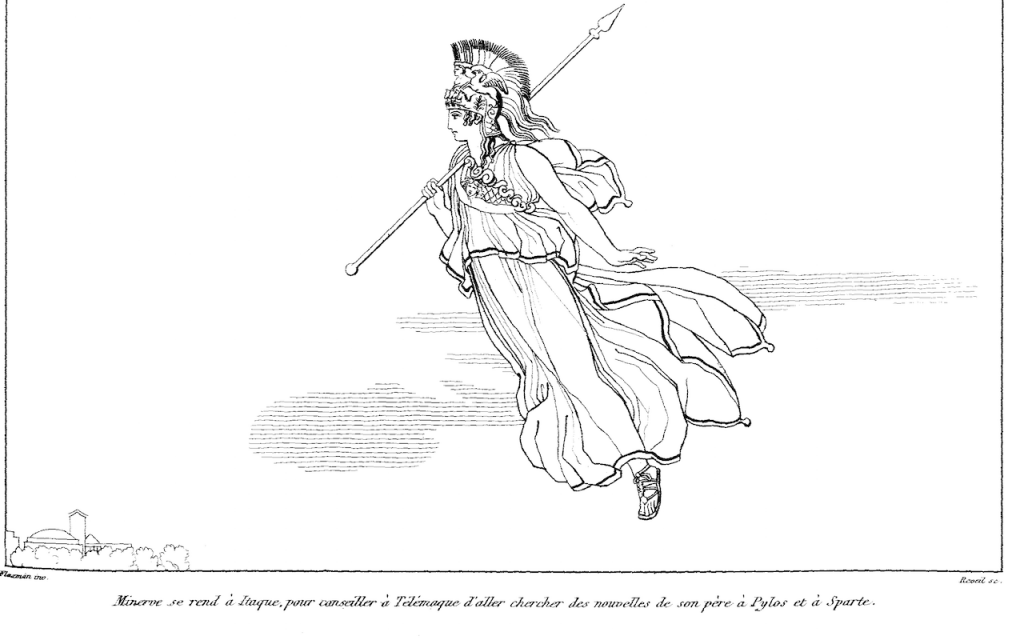

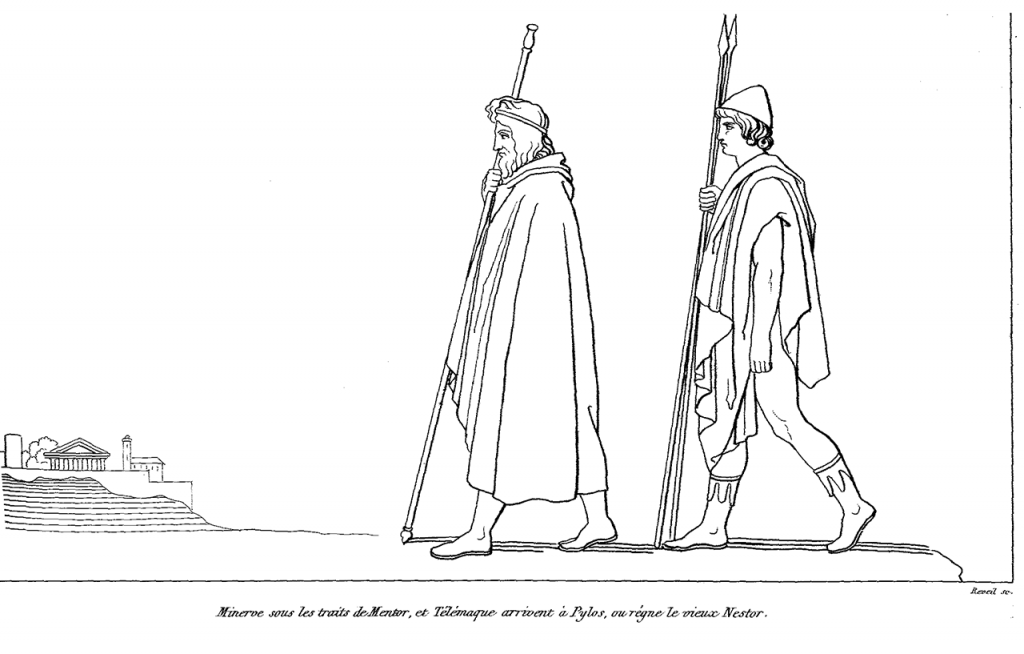

Figure 26.Telemachus with Athena as Mentor (1810). Drawing by John Flaxman. Image via Wikimedia Commons.

Figure 26.Telemachus with Athena as Mentor (1810). Drawing by John Flaxman. Image via Wikimedia Commons.O.02.001

O.02.006–008

O.02.026

O.02.032

O.02.035

O.02.037

O.02.044

O.02.047

O.02.067

O.02.080

O.02.085–128

O.02.092–109

O.02.121–122

O.02.163

O.02.212–218

O.02.224–228

O.02.225

O.02.234

O.02.239

O.02.262–269

O.02.271

O.02.282

O.02.313

O.02.323

O.02.350

O.02.360

Odyssey Rhapsody 3

2017.03.29 / enhanced 2018.10.06

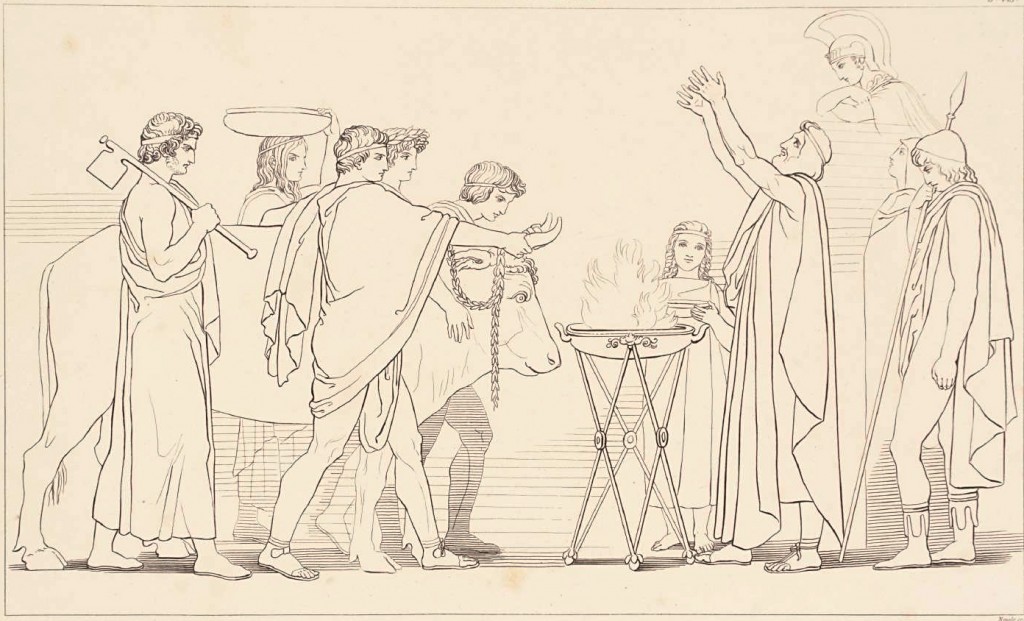

Figure 27. Nestor’s Sacrifice (1805). Engraving after John Flaxman (1755-1826). Purchased as part of the Oppé Collection with assistance from the National Lottery through the Heritage Lottery Fund 1996. Image released under Creative Commons CC-BY-NC-ND (3.0 Unported).

Figure 27. Nestor’s Sacrifice (1805). Engraving after John Flaxman (1755-1826). Purchased as part of the Oppé Collection with assistance from the National Lottery through the Heritage Lottery Fund 1996. Image released under Creative Commons CC-BY-NC-ND (3.0 Unported).O.03.001

O.03.033

O.03.036

O.03.066

O.03.083

O.03.112

O.03.118

O.03.120–121

O.03.130–183

O.03.130

O.03.133–135

O.03.160–169

O.03.168–169

O.03.170–178

O.03.202–224

O.03.207

O.03.262

O.03.267–271

O.03.267

O.03.464–468

Odyssey Rhapsody 4

2017.04.05 / enhanced 2018.10.06

Figure 28. “The Fair Helen.” Willy Pogany (Hungarian, 1882–1955). Image via Flickr user C. Ojeda, reproduced under a CC BY-NC-ND 2.0 license.

Figure 28. “The Fair Helen.” Willy Pogany (Hungarian, 1882–1955). Image via Flickr user C. Ojeda, reproduced under a CC BY-NC-ND 2.0 license.O.04.001–019

O.04.011

O.04.015–019

O.04.043–075

O.04.093–116

O.04.182–185

O.04.170

O.04.186–188

O.04.220–226

O.04.227–230

Σιδονίων, τὰς αὐτὸς Ἀλέξανδρος θεοειδὴς

ἤγαγε Σιδονίηθεν, ἐπιπλὼς εὐρέα πόντον,

τὴν ὁδὸν ἣν Ἑλένην περ ἀνήγαγεν εὐπατέρειαν.

ἐσθλά, τά οἱ Πολύδαμνα πόρεν Θῶνος παράκοιτις

Αἰγυπτίη, τῇ πλεῖστα φέρει ζείδωρος ἄρουρα

φάρμακα, πολλὰ μὲν ἐσθλὰ μεμιγμένα, πολλὰ δὲ λυγρά.

Αἰγύπτῳ μ’ ἔτι δεῦρο θεοὶ μεμαῶτα νέεσθαι

ἔσχον, ἐπεὶ οὔ σφιν ἔρεξα τεληέσσας ἑκατόμβας.

from Sidon, whom Alexandros [= Paris] himself, the godlike,

had brought home [to Troy] from the land of Sidon, sailing over the vast sea,

on the very same journey as the one he took when he brought back home [to Troy] also Helen, the one who is descended from the most noble father.

things of good outcome, which to her did Polydamna give, wife of Thon.

She was Egyptian. For her, many were the things produced by the life-giving earth,

magical things—many good mixtures and many baneful ones.

I was eager to return here, but the gods still held me in Egypt,

Since I had not sacrificed entire hecatombs [hekatombai] to them.

O.04.227

O.04.238–243

O.04.250

O.04.261

O.04.279

She [= Helen] was likening [eïskein] her voice to the voices of their wives.

O.04.341–344

O.04.343–344

O.04.351–362

O.04.351–353

O.04.354–355

O.04.363

O.04.489

O.04.512–522

O.04.512–513

O.04.561–569

O.04.567–568

O.04.727

O.04.739

O.04.809

Odyssey Rhapsody 5

2017.04.12 / enhanced 2018.10.07

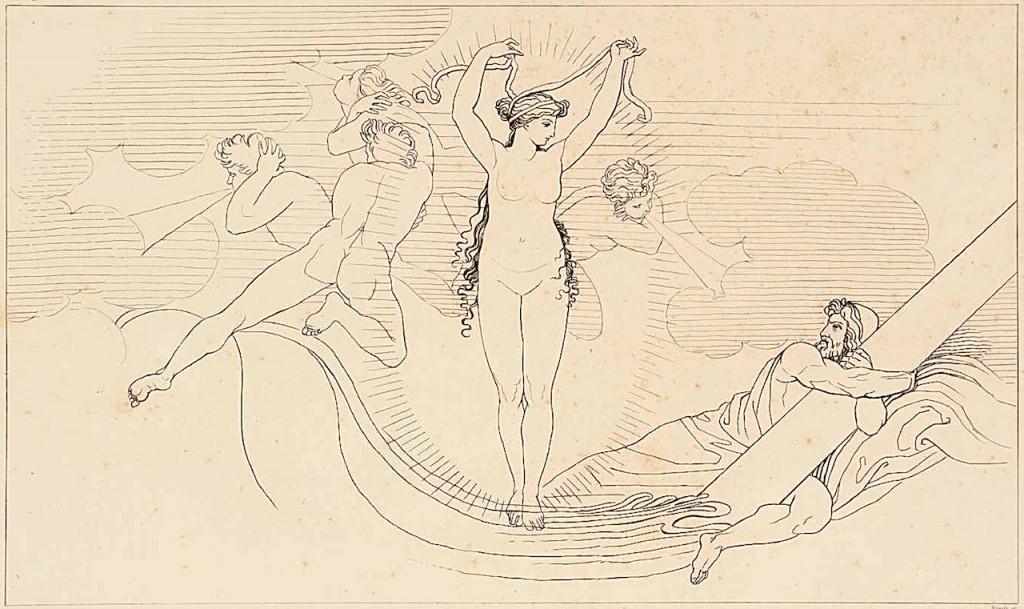

Figure 29. “Leucothea, the White Goddess, Preserving Ulysses” (1805). John Flaxman (1755–1826). Purchased as part of the Oppé Collection with assistance from the National Lottery through the Heritage Lottery Fund, 1996. Image via the Tate.

Figure 29. “Leucothea, the White Goddess, Preserving Ulysses” (1805). John Flaxman (1755–1826). Purchased as part of the Oppé Collection with assistance from the National Lottery through the Heritage Lottery Fund, 1996. Image via the Tate.O.05.001–002

O.05.047

O.05.121–124

O.05.121

O.05.123–124

O.05.136

O.05.160–161

O.05.185–186

O.05.248

O.05.273-275

O.05.308–311

O.05.333–353

O.05.396

O.05.432–435

O.05.437

O.05.458

O.05.493

Odyssey Rhapsody 6

2017.05.04 / enhanced 2018.10.07

Figure 30a. “Nausicaa” (1878), Frederick Leighton (English, 1830–1896). Image via Wikimedia Commons.

Figure 30a. “Nausicaa” (1878), Frederick Leighton (English, 1830–1896). Image via Wikimedia Commons.O.06.001–002

O.06.005–006

O.06.015–017

O.06.048–053

O.06.100–101

Figure 30b. Red-figured pyxis, picturing Nereids at home, “indoors”: the Nereid with her hair down is labeled as Thaleia. Image via The British Museum.

O.06.102–109

O.06.150–152

O.06.160–168

O.06.231

O.06.273

Odyssey Rhapsody 7

2017.05.11 / enhanced 2018.10.08

nous), king of the Phaeacians. This palace and the adjacent garden of Alkinoos are not only enchanting but even enchanted, as will be argued in the comments for Rhapsody 7 here. And, as we will see later in the comments for Rhapsody 13, the garden of Alkinoos was thought to have survived on the island of Kerkyra, known in Roman sources as Corcyra and in modern times as Corfù. In ancient times, the people of Kerkyra claimed that their island was in fact the fabled realm of the Phaeacians.[[GN 2017.05.11.]]

Figure 31. View of Garitsa, region right outside the northern walls of the city of Corfu, and according to the legend the site of Alcinous’s gardens (1867). Étienne Rey (French, 1789–1867). Image via the Aikaterini Laskaridis Foundation.

Figure 31. View of Garitsa, region right outside the northern walls of the city of Corfu, and according to the legend the site of Alcinous’s gardens (1867). Étienne Rey (French, 1789–1867). Image via the Aikaterini Laskaridis Foundation.O.07.058–062

O.07.078–081

O.07.081–111, 112–132

O.07.167

O.07.215–221

O.07.221

O.07.256

O.07.257

O.07.321

Odyssey Rhapsody 8

2017.05.18 / enhanced 2018.10.08

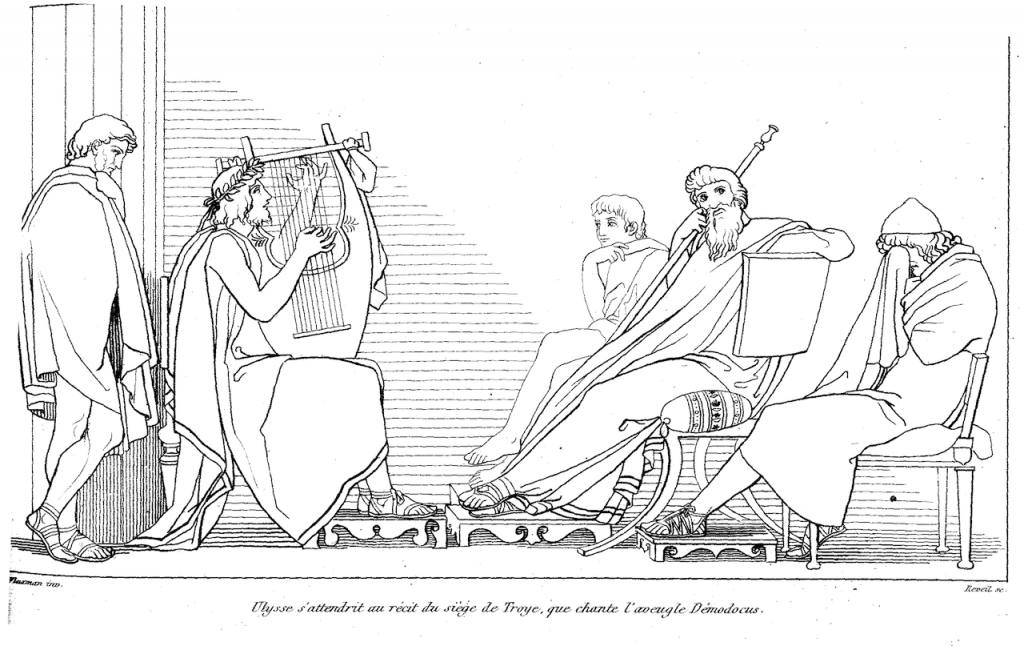

Figure 32. Blind Demodokos sings of the siege of Troy (1810), by John Flaxman (English, 1755–1826). Image via Wikimedia Commons.

Figure 32. Blind Demodokos sings of the siege of Troy (1810), by John Flaxman (English, 1755–1826). Image via Wikimedia Commons.O.08.002

O.08.026–045

O.08.036

O.08.038

O.08.044

O.08.059–061

O.08.061

O.08.062–095

O.08.067

O.08.071–072

O.08.073–082

O.08.073–074

O.08.074

O.08.075–078

O.08.079–081

O.08.081–082

O.08.094

O.08.096–103

O.08.099

O.08.131

O.08.200

O.08.230–233

O.08.250–269, 367–369

O.08.259

O.08.260

O.08.261–265

O.08.266

O.08.267

O.08.367–369

O.08.370–380

O.08.390–391

O.08.429

O.08.485–498

O.08.499–533

O.08.499

O.08.522

O.08.527

O.08.533

O.08.570–571

O.08.581–586

Odyssey Rhapsody 9

2017.05.25 / enhanced 2018.10.08

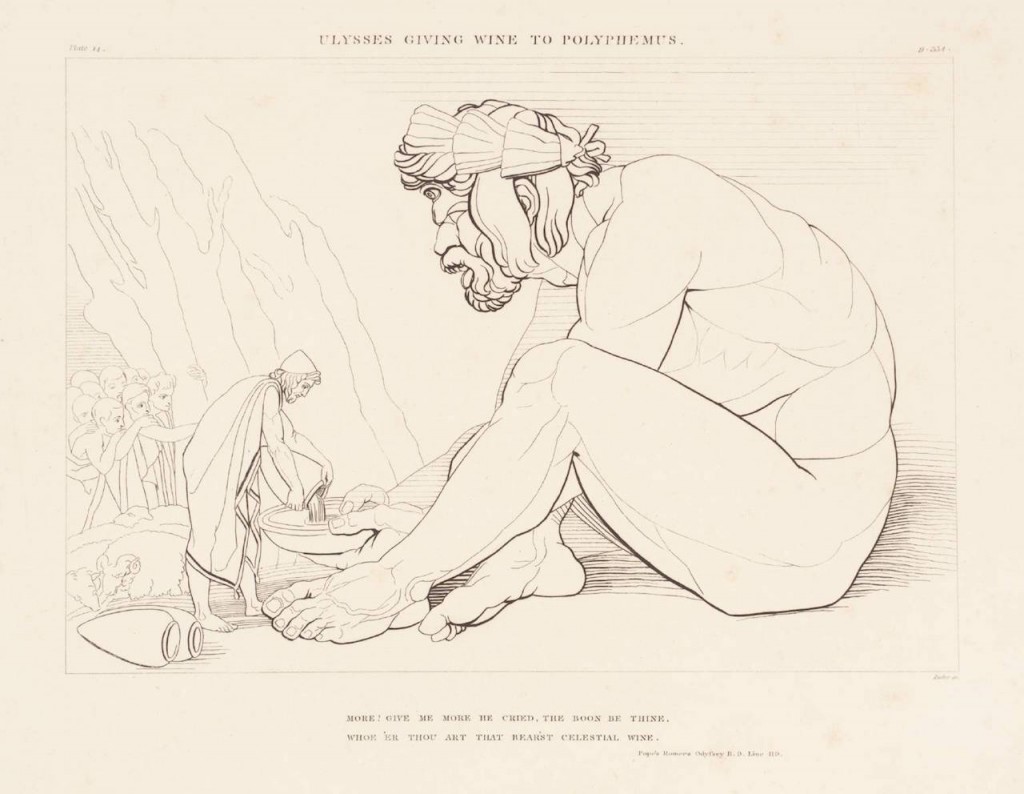

Figure 33. “Ulysses Giving Wine to Polyphemus” (1805). John Flaxman (1755–1826). Purchased as part of the Oppé Collection with assistance from the National Lottery through the Heritage Lottery Fund, 1996. Image via the Tate.

Figure 33. “Ulysses Giving Wine to Polyphemus” (1805). John Flaxman (1755–1826). Purchased as part of the Oppé Collection with assistance from the National Lottery through the Heritage Lottery Fund, 1996. Image via the Tate.O.09.003–011

O.09.019–020

O.09.063

O.09.082–104

O.09.106–141

O.09.125–129

O.09.125

O.09.133

O.09.355–422

O.09.390–394

O.09.566

Odyssey Rhapsody 10

2017.06.01 / enhanced 2018.10.08

Figure 34. “Circe Invidiosa,” (1892). J. W. Waterhouse (English, 1849–1917). Image via Wikimedia Commons.

Figure 34. “Circe Invidiosa,” (1892). J. W. Waterhouse (English, 1849–1917). Image via Wikimedia Commons.O.10.025–086

O.10.065

O.10.134

O.10.135

O.10.189–202

O.10.190–193

O.10.245

O.10.330–331

O.10.379

O.10.450

O.10.490–495

O.10.493

O.10.508–512

O.10.516–520

O.10.521–537

O.10.521

O.10.536

O.10.551–560

Odyssey Rhapsody 11

2017.06.08 / enhanced 2018.10.08

Figure 35. “Teiresias appears to Ulysses during the sacrifice,” (1780–1785). Henry Fuseli (German, 1741–1825). Image via Wikimedia Commons.

Figure 35. “Teiresias appears to Ulysses during the sacrifice,” (1780–1785). Henry Fuseli (German, 1741–1825). Image via Wikimedia Commons.O.11.012–019

O.11.020–022

O.11.024–036

O.11.029–036

O.11.029

O.11.051–083

O.11.075–078

O.11.090–137

O.11.091

O.11.099

O.11.100–118

O.11.119–137

O.11.124

O.11.136–137

O.11.138–224

O.11.151

O.11.179

O.11.201

O.11.217

O.11.222

O.11.225–329

O.11.290

O.11.296

O.11.300

O.11.330–385

O.11.433

O.11.467–540

O.11.475–476

O.11.478

O.11.489–491

O.11.550–551

O.11.558–560

O.11.568–571

O.11.597

O.11.601–626

O.11.601

O.11.620–624

O.11.631

O.11.636–640

Odyssey Rhapsody 12

2017.06.15 / enhanced 2018.10.08

Figure 36. “Ulysses and the Sirens” (ca. 1909). Herbert James Draper (English, 1863–1920). Image via Wikimedia Commons.

Figure 36. “Ulysses and the Sirens” (ca. 1909). Herbert James Draper (English, 1863–1920). Image via Wikimedia Commons.O.12.001–004

O.12.004

O.12.014–015

O.12.021–022

O.12.068

O.12.069–070

O.12.124

O.12.132

O.12.176

O.12.184–191

O.12.184

O.12.447–450

Odyssey Rhapsody 13

2017.06.22 / enhanced 2018.10.08

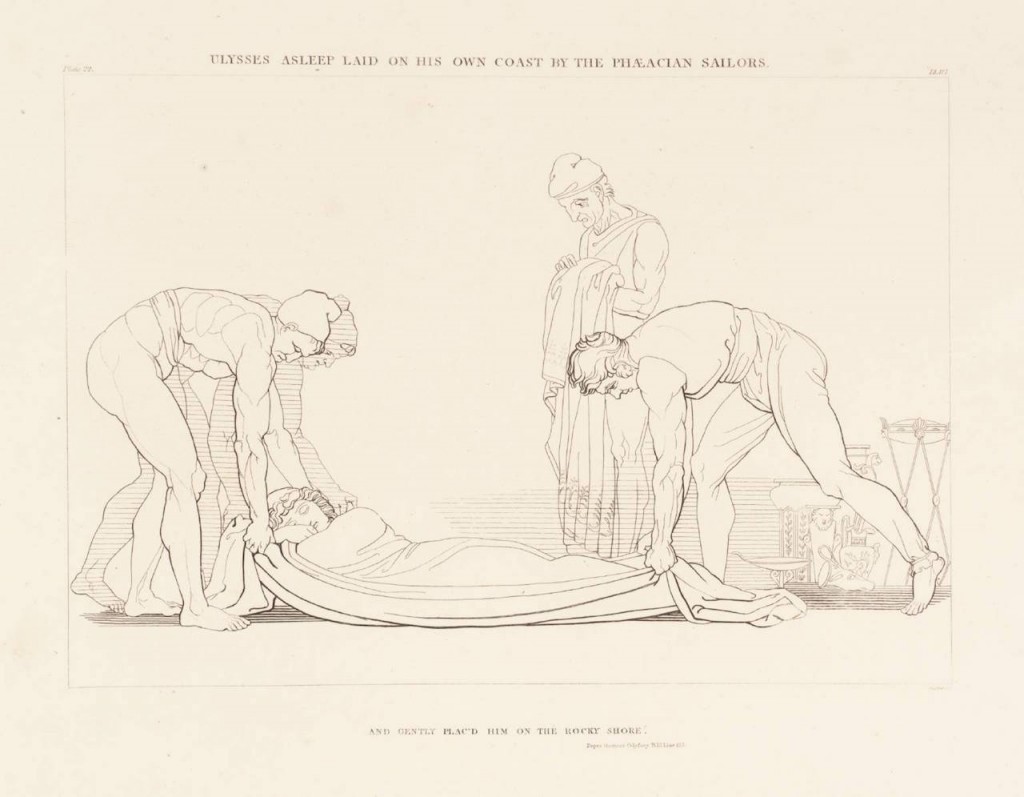

Figure 37. “Ulysses Asleep Laid on his Own Coast by the Phaeacian Sailors” (1805). John Flaxman (English, 1755–1826). Purchased as part of the Oppé Collection with assistance from the National Lottery through the Heritage Lottery Fund 1996. Image via the Tate.

O.13.023

O.13.024–028

O.13.024–025

O.13.027

O.13.028

O.13.078–095

O.13.081–083

O.13.149–152

O.13.155–158

O.13.158

O.13.160–164

O.13.165–169

O.13.175–177

O.13.178–179

O.13.180–182

O.13.182–183

O.13.182–183

O.13.187

O.13.256–286

O.13.299–310

Excursus on O.13.158

The formulation of Zeus, then, in leaving it still undecided whether or not the Phaeacians are to be ‘enveloped’, can be used as evidence to argue that mēde ‘but not…’ is indeed a genuine compositional alternative to mega de ‘and a huge…’.

Odyssey Rhapsody 14

2017.06.29 / enhanced 2018.10.09

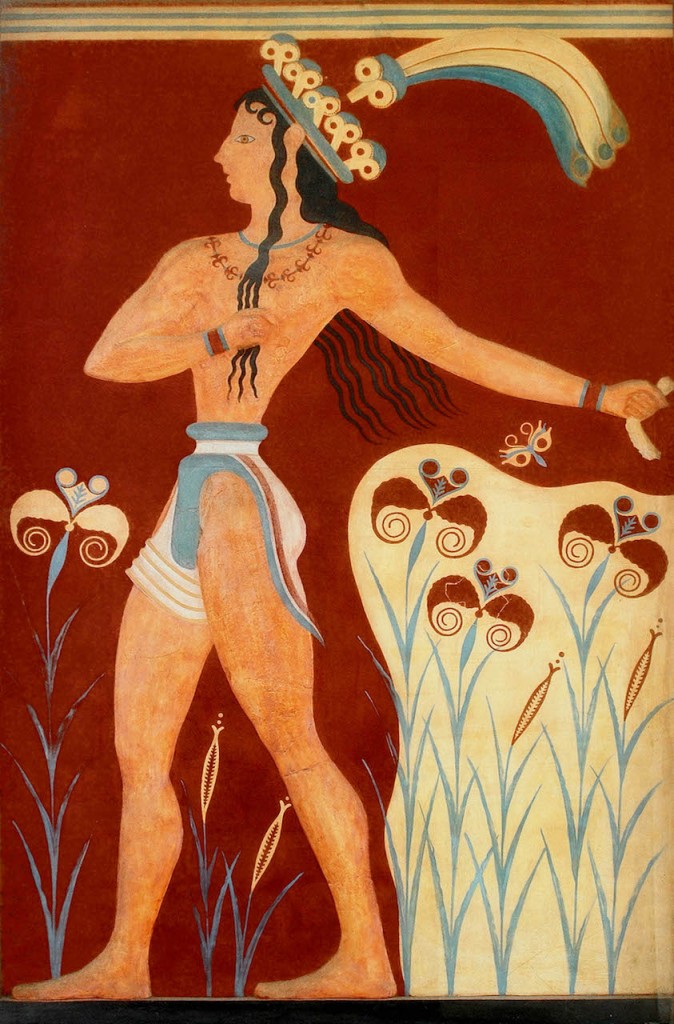

Figure 38. Minoan—probably Neopalatial—fresco commonly known as the “Lily Prince.” Whatever the exact type of this personage (perhaps a crowned acrobat, according to the interpretation of Maria Shaw), the Lily Prince is certainly a Minoan of elite standing. Public domain image based on a famous watercolor by Émile Gilliéron of a reconstruction by Arthur Evans. Image via Wikimedia Commons.

Figure 38. Minoan—probably Neopalatial—fresco commonly known as the “Lily Prince.” Whatever the exact type of this personage (perhaps a crowned acrobat, according to the interpretation of Maria Shaw), the Lily Prince is certainly a Minoan of elite standing. Public domain image based on a famous watercolor by Émile Gilliéron of a reconstruction by Arthur Evans. Image via Wikimedia Commons.O.14.055

O.14.063

O.14.109

O.14.124–125

O.14.126

O.14.135

O.14.192–359

O.14.199

O.14.216

O.14.337

O.14.371

O.14.403

O.14.418–438

O.14.440–441

O.14.462–506

O.14.462–467

O.14.508

Odyssey Rhapsody 15

2017.07.03 / enhanced 2018.10.12

Figure 39. Detail from a fresco found at Hagia Triadha in Crete. Reconstruction by Mark Cameron, p. 96 of the catalogue Fresco: A Passport into the Past. Minoan Crete through the eyes of Mark Cameron. 1999. Catalogue curated by Doniert Evely. Athens: British School at Athens; and N. P. Goulandris Foundation, Museum of Cycladic Art. Reproduced with the permission of the British School at Athens. BSA Archive: Mark Cameron Personal Papers: CAM 1.

Figure 39. Detail from a fresco found at Hagia Triadha in Crete. Reconstruction by Mark Cameron, p. 96 of the catalogue Fresco: A Passport into the Past. Minoan Crete through the eyes of Mark Cameron. 1999. Catalogue curated by Doniert Evely. Athens: British School at Athens; and N. P. Goulandris Foundation, Museum of Cycladic Art. Reproduced with the permission of the British School at Athens. BSA Archive: Mark Cameron Personal Papers: CAM 1.O.15.001–009

O.15.001–003

O.15.140

O.15.247

O.15.249

O.15.250–251

O.15.253

O.15.305

O.15.329

O.15.341–342

O.15.491

O.15.521–522

Odyssey Rhapsody 16

2017.07.06 / enhanced 2018.10.12

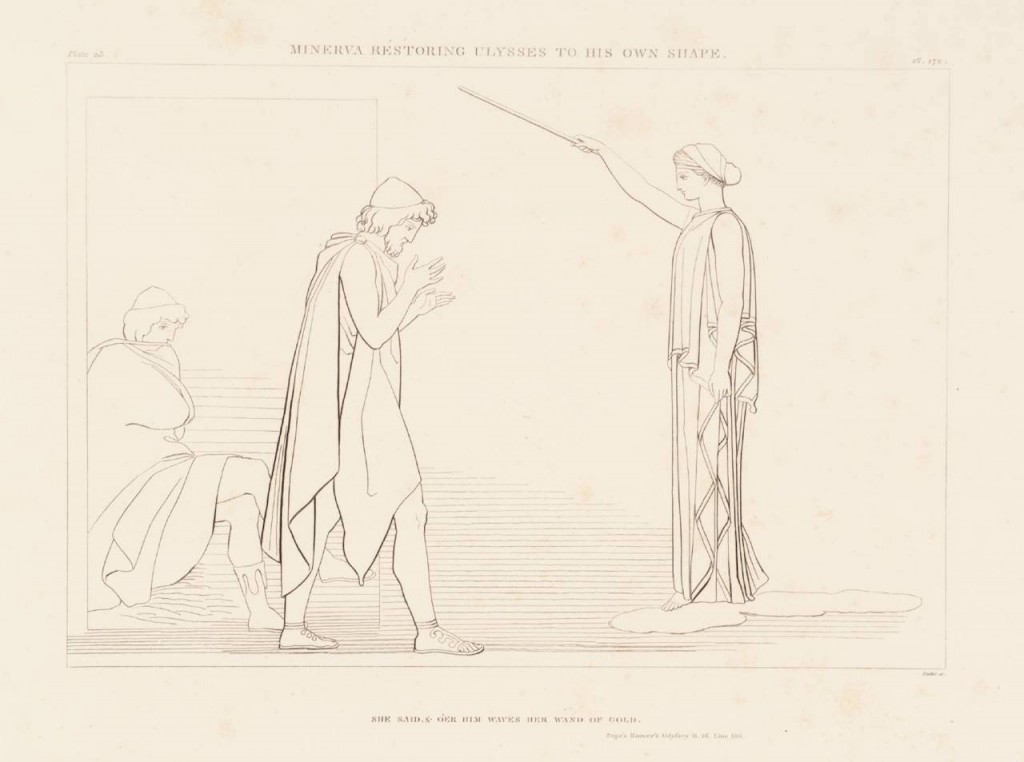

Figure 40. “Minerva Restoring Ulysses to his Own Shape” (1805). John Flaxman (English, 1755–1826). Purchased as part of the Oppé Collection with assistance from the National Lottery through the Heritage Lottery Fund 1996. Image via the Tate.

Figure 40. “Minerva Restoring Ulysses to his Own Shape” (1805). John Flaxman (English, 1755–1826). Purchased as part of the Oppé Collection with assistance from the National Lottery through the Heritage Lottery Fund 1996. Image via the Tate.O.16.062–064

O.16.076

O.16.086

O.16.161

O.16.164

O.16.172–212

O.16.214

O.16.283

O.16.418–432

Odyssey Rhapsody 17

2017.07.13 / enhanced 2018.10.13

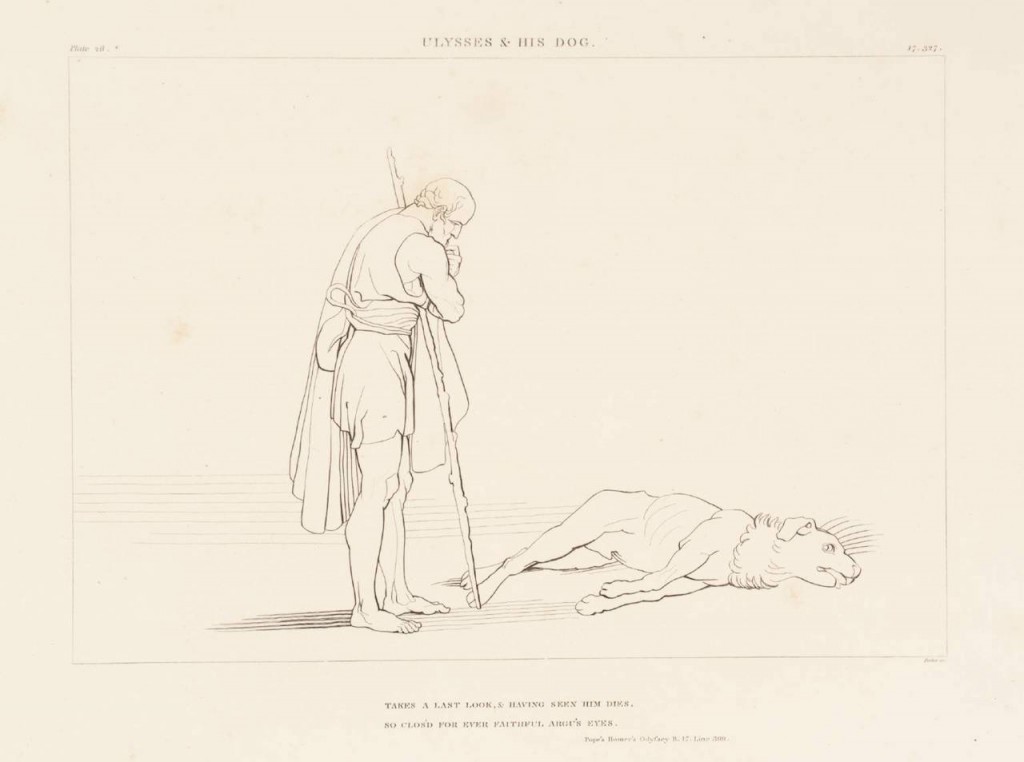

Figure 41. “Ulysses and his Dog” (1805). John Flaxman (English, 1755–1826). Purchased as part of the Oppé Collection with assistance from the National Lottery through the Heritage Lottery Fund 1996. Image via the Tate. “Ulysses Preparing to Fight with Irus” (1805). John Flaxman (English, 1755–1826) Purchased as part of the Oppé Collection with assistance from the National Lottery through the Heritage Lottery Fund 1996. Image via the Tate.

Figure 41. “Ulysses and his Dog” (1805). John Flaxman (English, 1755–1826). Purchased as part of the Oppé Collection with assistance from the National Lottery through the Heritage Lottery Fund 1996. Image via the Tate. “Ulysses Preparing to Fight with Irus” (1805). John Flaxman (English, 1755–1826) Purchased as part of the Oppé Collection with assistance from the National Lottery through the Heritage Lottery Fund 1996. Image via the Tate.O.17.011

O.17.019

O.17.056

O.17.062

O.17.111

O.17.113

O.17.228

O.17.251–253

O.17.261–263

O.17.273–289

O.17.292

O.17.332

O.17.336–368

O.17.381–391

O.17.381–391

O.17.384–385

O.17.494

O.17.496–497

O.17.513–521

Odyssey Rhapsody 18

2017.07.20 / enhanced 2018.10.13

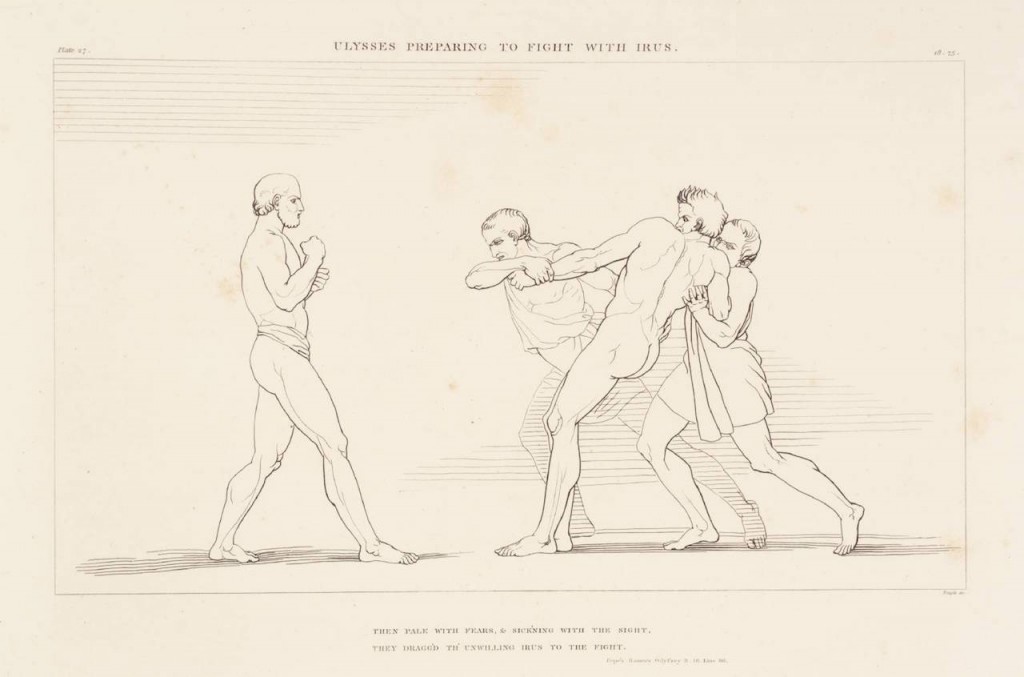

Figure 42. “Ulysses Preparing to Fight with Irus” (1805). John Flaxman (English, 1755–1826) Purchased as part of the Oppé Collection with assistance from the National Lottery through the Heritage Lottery Fund 1996. Image via the Tate.

Figure 42. “Ulysses Preparing to Fight with Irus” (1805). John Flaxman (English, 1755–1826) Purchased as part of the Oppé Collection with assistance from the National Lottery through the Heritage Lottery Fund 1996. Image via the Tate.O.18.001–117

O.18.001–004

The fox knows many things, but the hedgehog knows one big thing.

The fox knows many things, but the hedgehog knows one big thing.

O.18.006–007

O.18.009

O.18.015–019

O.18.073–074

O.18.079–087

O.18.085–087

O.18.115–116

O.18.204

O.18.233

O.18.235–240

O.18.289

O.18.321–326

O.18.347

O.18.350

O.18.366–386

O.18.390

O.18.424

Odyssey Rhapsody 19

2017.07.24 / enhanced 2018.10.13

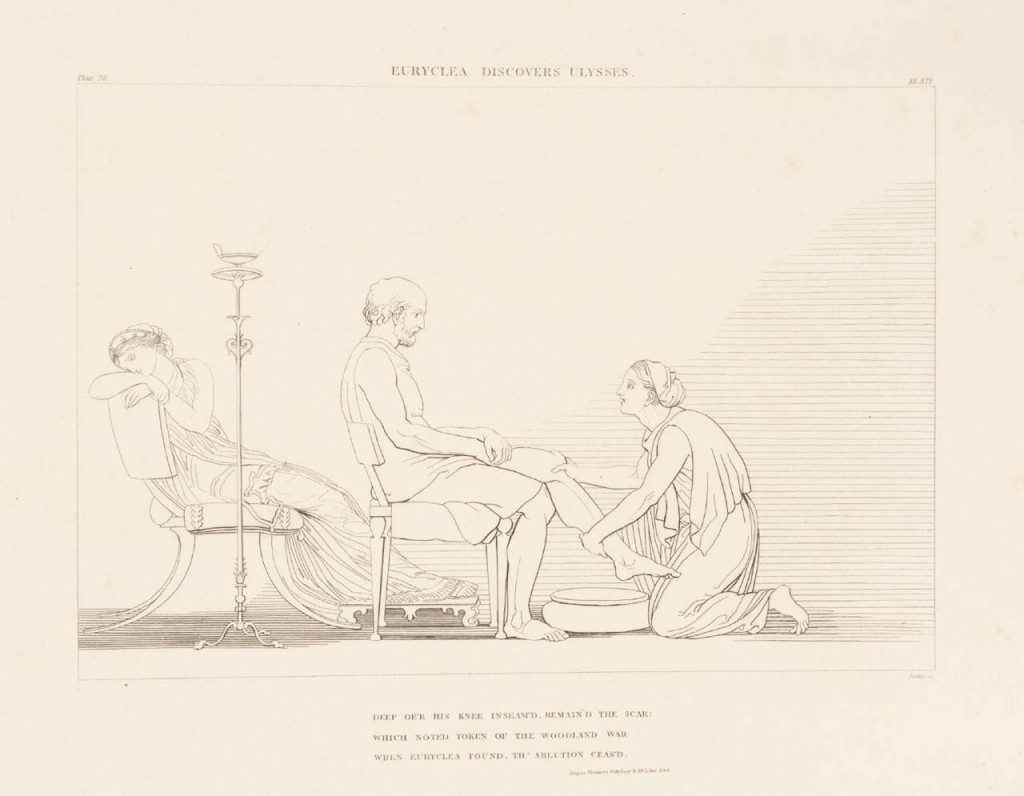

Figure 43. “Euryclea Discovers Ulysses” (1805). John Flaxman (English, 1755–1826). Purchased as part of the Oppé Collection with assistance from the National Lottery through the Heritage Lottery Fund 1996. Image via the Tate.

Figure 43. “Euryclea Discovers Ulysses” (1805). John Flaxman (English, 1755–1826). Purchased as part of the Oppé Collection with assistance from the National Lottery through the Heritage Lottery Fund 1996. Image via the Tate.O.19.107–114

O.19.135

O.19.136

O.19.163

‘For surely you are not from an oak, going back to an old saying, or from a rock.’

O.19.165–203

O.19.172–193

O.19.177

O.19.178

O.19.183

O.19.185–193

O.19.188

Amnisos: Eleuthiāi meli [followed by the ideogram for “amphora”] 1

‘Amnisos: for Eleuthia, honey, one amphora’.

O.19.203

‘He made likenesses [eïskein], saying many deceptive [pseudea] things looking like [homoia] genuine [etuma] things.’

O.19.204–212

O.19.215–248

O.19.250

O.19.255–257

O.19.264

O.19.309–316

O.19.320

O.19.325–334

O.19.334

O.19.331

O.19.370–374

O.19.388–507

O.19.433–434

O.19.440

O.19.518–523

O.19.521

O.19.522

O.19.528

O.19.535–565

O.19.535

‘Come, respond [hupo-krinesthai] to my dream [oneiros], and hear my telling of it.’

O.19.547

O.19.562–569

O.19.562

Odyssey Rhapsody 20

2017.08.03 / enhanced 2018.10.13

Figure 44. “The Harpies Going to Seize the Daughters of Pandareus” (1805). John Flaxman (English, 1755–1826). Purchased as part of the Oppé Collection with assistance from the National Lottery through the Heritage Lottery Fund 1996. Image via the Tate.

Figure 44. “The Harpies Going to Seize the Daughters of Pandareus” (1805). John Flaxman (English, 1755–1826). Purchased as part of the Oppé Collection with assistance from the National Lottery through the Heritage Lottery Fund 1996. Image via the Tate.O.20.061–080

O.20.061

O.20.087–090

O.20.098–121

O.20.204–205

O.20.263

O.20.266

O.20.276–280

O.20.285

O.20.292–302

O.20.335

O.20.346

O.20.354

O.20.367–368

Odyssey Rhapsody 21

2017.08.10 / enhanced 2018.10.13

Figure 45a. Hēraklēs stringing a bow. Silver stater, c. 450–440 BCE, Thebes (Boeotia). Image via Wikimedia Commons.

Figure 45a. Hēraklēs stringing a bow. Silver stater, c. 450–440 BCE, Thebes (Boeotia). Image via Wikimedia Commons.O.21.026

O.21.110

O.21.185

O.21.205

O.21.217–224

O.21.253–255

O.21.288–310

O.21.314–316

O.21.267

O.21.402–403

Figure 45b. Swallows, detail of the Spring Fresco at Thera, image via Flickr user F. Tronchin, reproduced under a CC BY-NC-ND 2.0 license.

Figure 45b. Swallows, detail of the Spring Fresco at Thera, image via Flickr user F. Tronchin, reproduced under a CC BY-NC-ND 2.0 license.O.21.404–411

Figure 45c. Original artwork, by Flickr user Veronica Roth, reproduced under a CC BY-NC-ND 2.0 license.

Figure 45c. Original artwork, by Flickr user Veronica Roth, reproduced under a CC BY-NC-ND 2.0 license.O.21.429–430

O.21.429

Odyssey Rhapsody 22

2017.08.17 / enhanced 2018.10.13

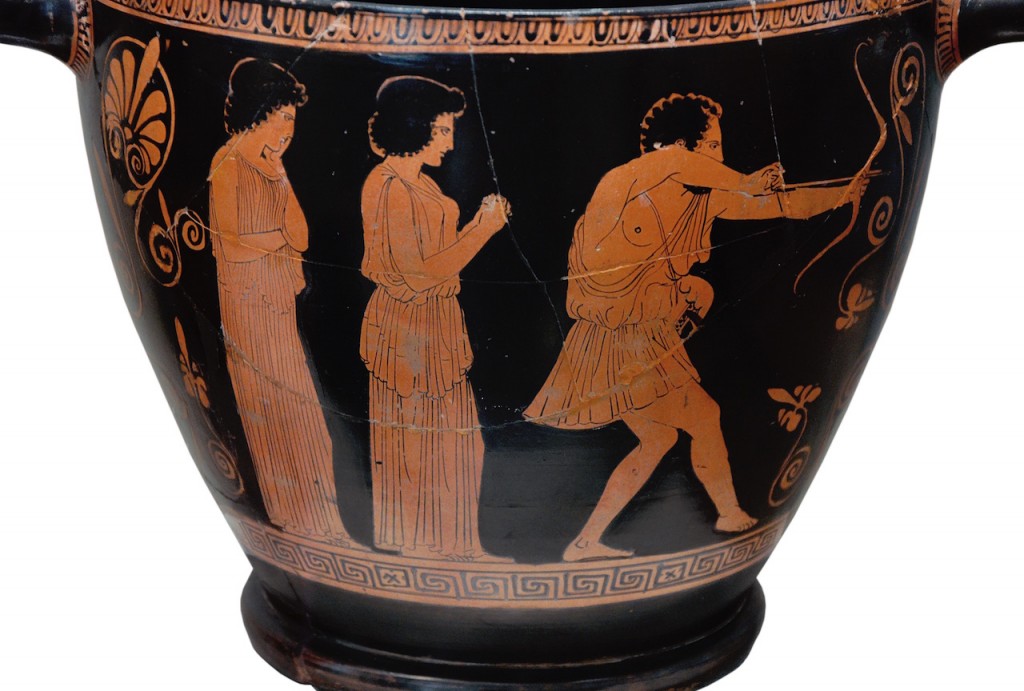

Figure 46a. Odysseus kiling Penelope’s suitors. Attic red-figure skyphos, ca. 440 BCE. Image via Wikimedia Commons.

Figure 46a. Odysseus kiling Penelope’s suitors. Attic red-figure skyphos, ca. 440 BCE. Image via Wikimedia Commons.O.22.001-125

O.22.001-021

O.22.001–007

This description captures the high drama of Homeric performance, as here at the beginning of Rhapsody 22. [[GN 2017.08.16 via HC 3§198.]]

O.22.005

O.22.027–033

O.22.031–033

O.22.203

O.22.285–291

O.22.330–380

O.22.330–331

O.22.347

O.22.376

O.22.437–479.

Figure 46b. Still life showing eggs, thrushes, napkin: from the House of Julia Felix, Pompeii. Image via Wikimedia Commons.

O.22.498

Odyssey Rhapsody 23

2017.08.23 / enhanced 2018.10.13

O.23.031

Figure 47a. Eurykleia waking Penelope (1773). Print by Thomas Burke, after a painting by Angelika Kauffmann. Image via the British Museum.

Figure 47a. Eurykleia waking Penelope (1773). Print by Thomas Burke, after a painting by Angelika Kauffmann. Image via the British Museum.O.23.073–077

O.23.107–230

O.23.130–151

O.23.143–147

O.23.156–163

O.23.163

Figure 47b. Big Ed and Norma have just now broken free of the troublesome relationships that have kept these lovers apart for 27 years. Now at long last they can have a life together. Still from Twin Peaks 3 Episode 15, reworked by Jill Curry Robbins.

O.23.246

O.23.264–284

O.23.271

O.23.296

O.23.310–343

Odyssey Rhapsody 24

2017.08.31 / enhanced 2018.10.13

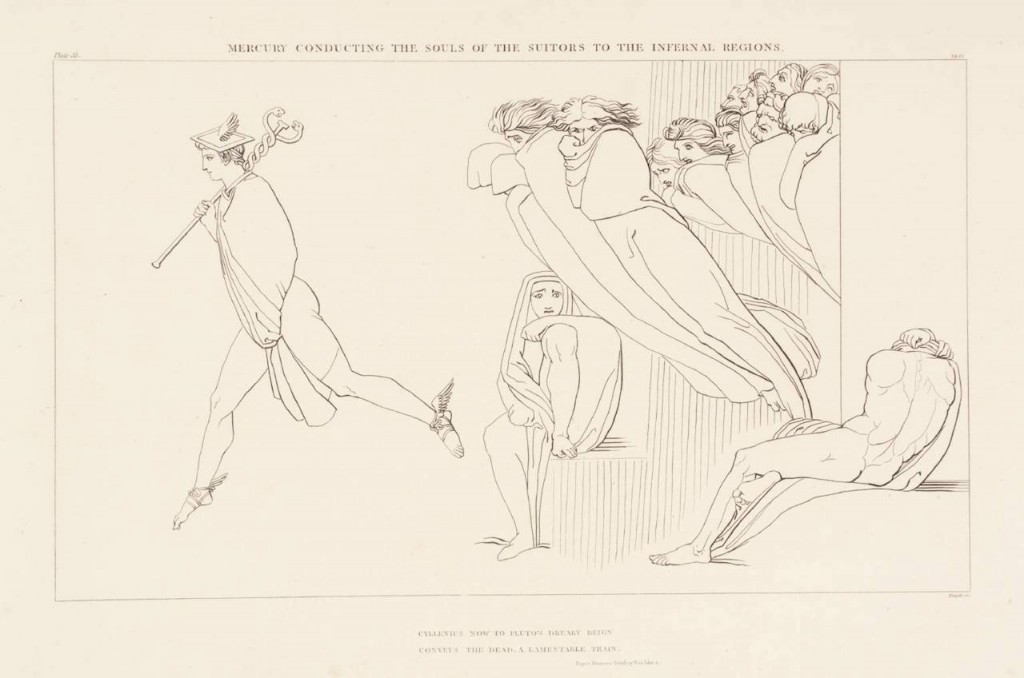

Figure 48a. “Mercury Conducting the Souls of the Suitors to the Infernal Regions” (1805). John Flaxman (English, 1755–1826). Purchased as part of the Oppé Collection with assistance from the National Lottery through the Heritage Lottery Fund 1996. Image via the Tate.

Figure 48a. “Mercury Conducting the Souls of the Suitors to the Infernal Regions” (1805). John Flaxman (English, 1755–1826). Purchased as part of the Oppé Collection with assistance from the National Lottery through the Heritage Lottery Fund 1996. Image via the Tate.O.24.001–014

O.24.002–003

O.24.014–023

O.24.016

O.24.023–098

O.24.024–034

O.24.030–034

O.24.036–097

O.24.058–061

O.24.076–084

O.24.080–084

O.24.094

O.24.107–108

O.24.121–190

O.24.161

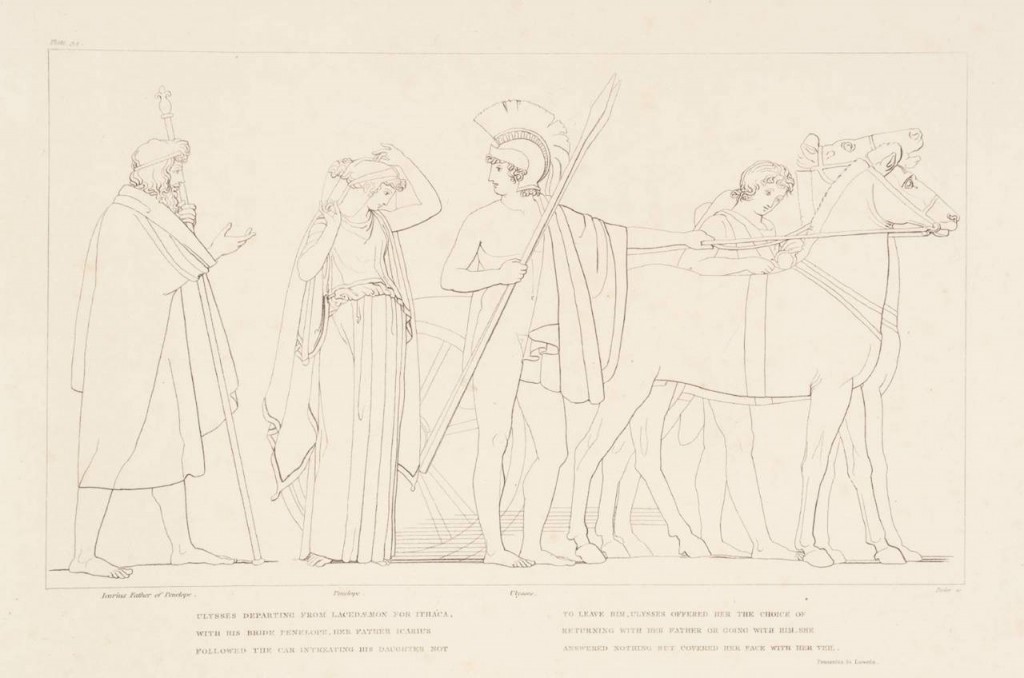

Figure 48b. “Ulysses Departing from Lacedaemon for Ithaca, with his Bride Penelope” (1805). John Flaxman (English, 1755–1826). Flaxman made this image the last in his Odyssey series, bringing the story of Penelope and Odysseus full circle. Purchased as part of the Oppé Collection with assistance from the National Lottery through the Heritage Lottery Fund 1996. Image via the Tate.