[[First published in ΙΜΕΡΟΣ 5.1 (2005) 311-317.]]

To refer to this essay, please cite it in this way:

G. Nagy, “An Apobatic Moment for Achilles as Athlete at the Festival of the Panathenaia,” https://chs.harvard.edu/publications, Center for Hellenic Studies, Washington, DC, 2009

This presentation focuses on two Black Figure paintings, both dated around 510 BCE, that depict the athletic event of the apobatōn agōn, which means ‘contest of the apobatai’ or ‘apobatic contest’. [1] These paintings are found on vases to which I will refer simply as the Boston Hydria [2] and the Münster Hydria. [3] The event that is being depicted, which was part of the athletic program of the festival of the Panathenaia in Athens, featured a spectacular “sudden-death” moment of athletic bravura. We can imagine all eyes focused on the action that leads up to that moment, when the competing athlete, riding on the platform of a four-horse chariot driven at full gallop by his charioteer, suddenly leaps to the ground from the speeding chariot. The term for such an athlete is apobatēs, meaning literally ‘he who steps off’. [4] At the death-defying moment when he literally steps off the platform of the speeding chariot, the apobatēs is fully armed in the armor of a warrior. The various attested representations in the visual arts show the apobatēs armed with helmet, breastplate, shinguards, spear, sword, and shield. [5] Weighed down by all this armor, the apobatēs must hit the ground running as he lands on his feet from his high-speed leap from the platform of his chariot. If his run is not broken by a fall, he continues to run down the length of the racecourse in competition with the other running apobatai who have made their own simultaneous leaps from their own chariots. [6] In one of the two paintings that I will be considering, as well as in other paintings, the athletic event of this apobatic contest is correlated with an epic event that takes place in the Homeric Iliad. The hero Achilles, infuriated over the killing of his dearest friend Patroklos by Hektor, tries to avenge this death by dragging behind his speeding chariot the corpse of Hektor (XXII 395-405, XXIV 14-22). [7] In the painting on the Boston Hydria, we see Achilles at the precise moment when he cuts himself off from the act of dragging the corpse of Hektor. This moment is synchronized with the precise moment when he leaps off, in the mode of an apobatēs, from the platform of the chariot that is dragging the corpse. The leap of Achilles here is the leap of the apobatēs. This moment, captured in the painting we see on the Boston Hydria, is what I am calling the apobatic moment. I will argue that this moment can be understood only in the context of the poetic as well as athletic program of the Panathenaia.

The first time that the Iliad pictures Achilles dragging the corpse of Hektor, the event is witnessed by the dead hero’s mother, father, and wife: Hecuba, Priam, and Andromache all lament the terror and the pity of it all (XXII 405-407, 430-436; 408-429; 437-515).

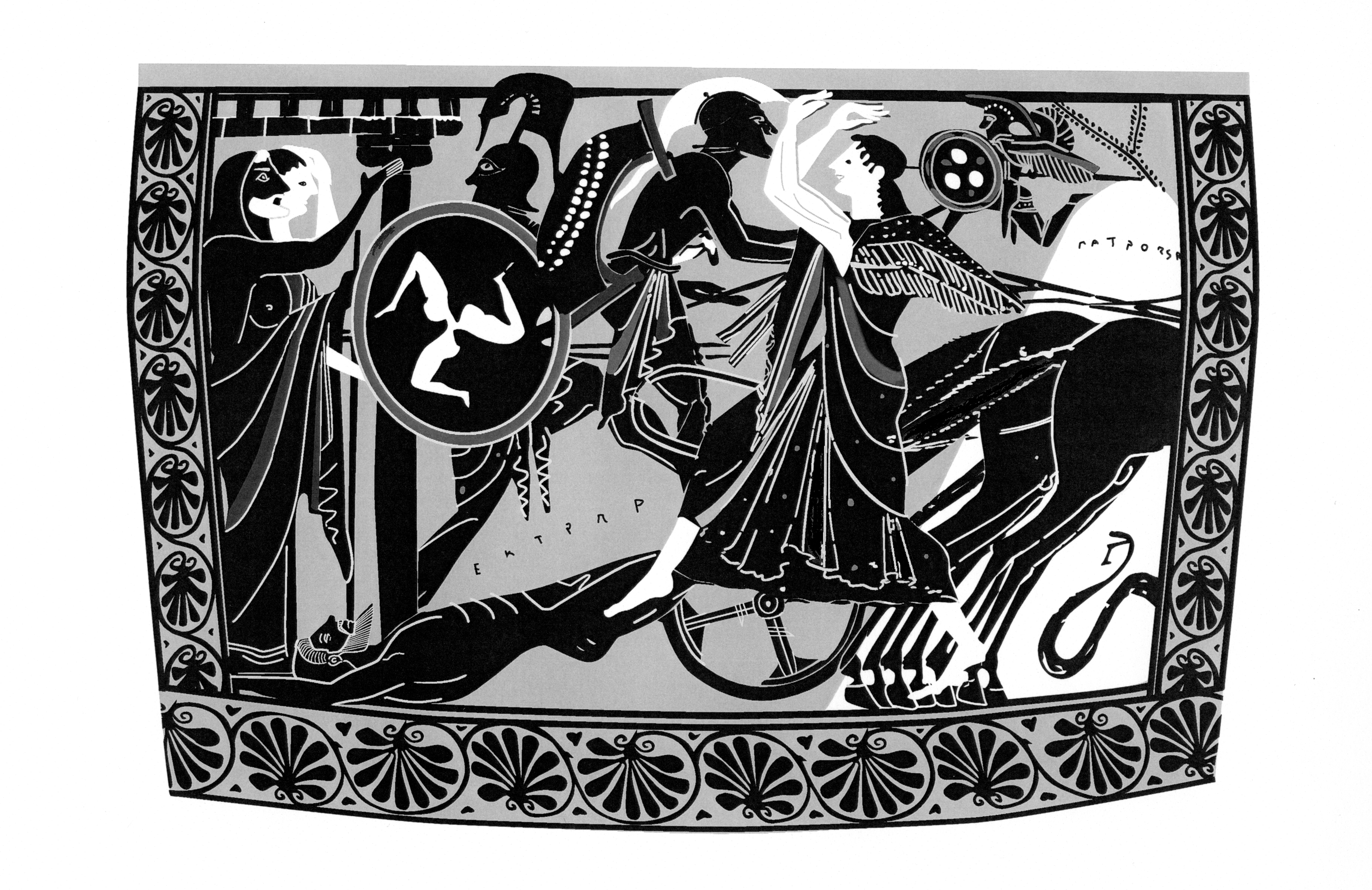

As in the Iliad, the lamenting figures of Hecuba and Priam are pictured on one of the two Black Figure vases that presently concern me, the Boston Hydria [[see Illustration 1]]. This vase, like the Iliad, pictures Achilles dragging the corpse of Hektor – while the lamenting figures of Hecuba and Priam view this scene of terror and pity from a portico.

Illustration 1. “Boston Hydria.” Attic black-figure hydria: Achilles dragging the body of Hector. Attributed to the Antiope Group. Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, 63.473. Drawing by Valerie Woelfel.

The next time the Iliad pictures Achilles dragging the corpse of Hektor behind his chariot, we see that chariot being driven three times around the sēma ‘tomb’ of Patroklos (XXIV 14-18). At an earlier point in the narrative of the Iliad, this tomb is described as incomplete: it will not be complete until Achilles himself is buried there together with his friend Patroklos (XXIII 83-84, 91-92, 245-248).

As in the Iliad, this tomb of Patroklos is pictured on the Boston Hydria [[again, Illustration 1]]. The chariot of Achilles is shown furiously circling around the tomb, with the corpse of Hektor in tow, and we see the hero at the very moment when he leaps off the speeding chariot, with his fierce gaze fixed on the portico where Priam and Hecuba lament the cruel fate of their son.

Every time we look through the painted window that frames this painted moment, we return to this same precise moment. As Emily Vermeule says, “The technique gives the impression that the myth is circling around in another world, outside the window frame through which the spectator views it, in endless motion which is somehow always arrested at the same place whenever we return to the window.” [8] This moment is the critical moment of the apobatēs, the apobatic moment.

In the Iliad, a council of the gods is convened, which expresses its moral disapproval of Achilles for his attempt to mutilate the corpse of Hektor by dragging it behind his chariot (XXIV 22-76). Earlier in the narrative of the Iliad, we see that the god Apollo had miraculously prevented the actual mutilation of the corpse (18-21). But now the council of the gods, headed by Zeus, decides to go one step further: the dragging of the corpse by Achilles must stop altogether. The divine course of action in stopping Achilles is explicitly said to be indirect: Iris as messenger of the gods is sent off to summon Thetis (74-75), who will be asked by Zeus to persuade her son to return the corpse of Hektor to Priam (75-76); then Iris is sent off to Priam, who will receive from the goddess a divine plan designed to make it possible for him to persuade Achilles to return the corpse of his son (143-158).

By contrast with the narration of the Iliad, the divine course of action narrated by the painting on the Boston Hydria is explicitly direct: the goddess sent from on high will personally stop the dragging of the corpse of Hektor by Achilles. The painting shows the goddess at the moment of her landing: she touches ground at the center of the picture, with feet gracefully poised as if in a dance, and her gesture of lament evokes pity as she looks toward the lamenting Priam and Hecuba, whose own gesture of lament evokes pity as they look toward Achilles. The fierce gaze of the furious hero is at this point redirected at Priam and Hecuba, who take their cue, as it were, from the gesture of lament shown by the goddess. The gaze of Achilles is thus directed away from the figure of Patroklos, who is shown hovering over a tomb that for now belongs only to him but will soon belong to Achilles as well. The charioteer of Achilles, oblivious to the intervention of the goddess, continues to drive the speeding chariot around the tomb, but, meanwhile, we find Achilles in the act of stepping off the platform. And he steps off at the precise moment when he redirects his gaze from his own past and future agony to the present agony of Hektor’s lamenting father and mother. Here is the hero’s apobatic moment.

The pity of Achilles for the parents of Hektor in the painting of the Boston Hydria is achieved by way of a direct divine intervention that takes place while the dragging of the corpse is in progress. Once Achilles steps off his furiously speeding chariot, the fury that fueled that speed must be left behind as he hits the ground running and keeps on running until the fury is spent.

To be contrasted is the pity of Achilles for the father of Hektor in the Iliad as we have it. This pity cannot be achieved with any direct divine intervention while the dragging of the corpse is in progress. In this case, the divine intervention is indirect: it is only after the gods guide Priam behind enemy lines to the tent of Achilles that the lamenting father succeeds in evoking the pity that the Iliadic hero will ultimately feel in Iliad XXIV.

Aside from this divergence between the painted and the poetic versions of the narrative, the convergences far outweigh the divergences, and I infer that the internal logic of the Iliadic narrative that we see at work in the visual medium of the Boston Hydria is morphologically parallel to the internal logic of the Iliadic narrative that we see at work in the verbal medium of the Homeric Iliad as we know it.

It does not follow, however, that the narrative of the painting must be derived from the narrative of the Iliad as we know it. Such a further inference is unjustified. It would be simplistic to think that a narrative inherent in a painting that dates from around 510 BCE must be derived from the narrative of an epic tradition that happens to be current in the same era. The visual medium of heroic narrative by way of painting is not dependent on the verbal medium of heroic narrative by way of poetry. Rather, both media of heroic narrative are dependent on the more basic principle of making contact with the traditional world of heroes – who are honored by way of ritual as well as myth. As I have argued extensively elsewhere, the rules of heroic narrative in the archaic period of Greek civilization were governed by the myths and rituals linke d with the cult of heroes. [9] And what applies to the medium of poetry applies also to the medium of painting.

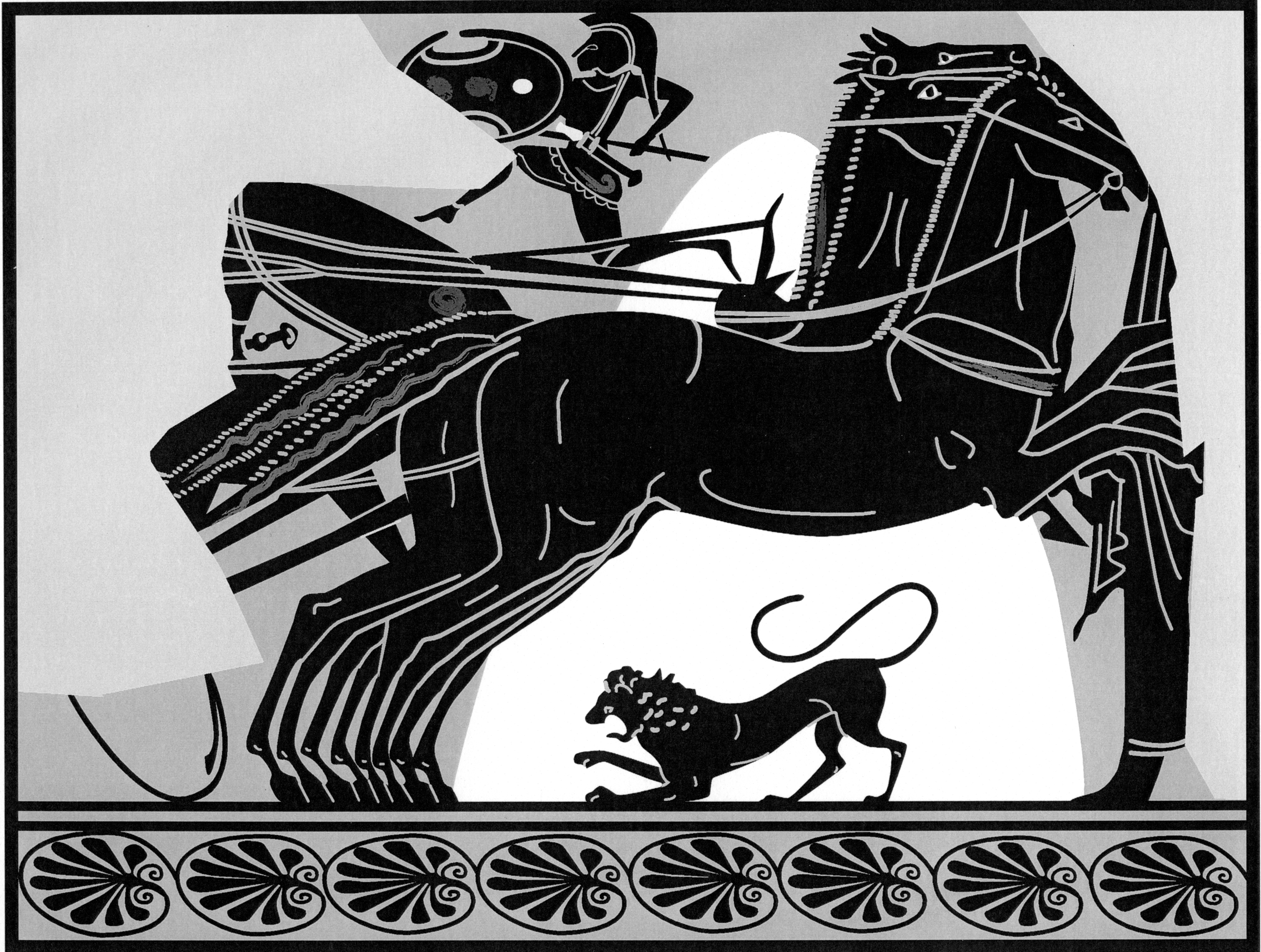

In the case of the Black Figure painting that we see on the Boston Hydria, the medium of the painting is evidently referring to a specific context, that is, to the festival of the Panathenaia in Athens around 510 BCE, featuring the athletic event of the apobatic contest. The same can be said about the Black Figure painting we see on the Münster Hydria [[Illustration 2]]. In this second painting, Achilles is represented as engaging in a personalized apobatic race with himself. In the narrative of the Münster Hydria, Achilles is seen running alongside the speeding chariot. He has already leapt off its platform. Meanwhile, the psukhē or ‘spirit’ of Patroklos is shown hovering over his tomb or sēma, which occupies the dead center of the picture. He is running in the air – a miniature version of the running Achilles who is racing at ground zero with his other self.

Illustration 2. “Münster Hydria.” Attic black-figure hydria: Achilles dragging Hector around the tomb of Patroclus. Attributed to the Leagros Group. Münster, Wilhelms-Universität, 565. Drawing by Valerie Woelfel.

In the Münster Hydria [[Illustration 2]], as in the Boston Hydria [[Illustration 1]], a goddess directly intervenes. The figure of this goddess, just barely visible on the fragmentary right side of the picture, is standing in the way of the onrushing chariot. Meanwhile, a council of the gods is in session on high – in a picture framed on the shoulder of the vase, situated above the main picture framed along the body of the vase [[Illustration 3]].

Illustration 3. View of the image painted on the shoulder of the Münster Hydria. Drawing by Valerie Woelfel.

It has been argued that the main picture on the Münster Hydria represents the notional beginnings of a hero cult shared by Achilles with his other self Patroklos. [10] The two of them preside as cult heroes of the athletic event of the apobatai at the festival of the Panathenaia. The death of Patroklos, which is the prototype for the death of Achilles himself, is figured as the aetiology of this athletic event, which shows the ritual dimension of the cult hero as a complement to the mythical dimension that we see played out in narratives conveyed by painting as well as by poetry. [11] The painting on the Münster Hydria shows Achilles as a prototypical participant in this hero cult by way of participating in this athletic event. Through his prototypical participation, Achilles shows the way for future athletes to participate in this athletic event of the apobatai at the seasonally recurring festival of the Panathenaia for all time to come.

A parallel argument can be made about the Funeral Games of Patroklos in Iliad XXIII. [12] Here too Achilles is shown as a prototypical participant in the hero cult of his other self, Patroklos. Here too he shows the way for future athletes to participate in his own hero cult by way of participating in the athletic events we see described in Iliad XXIII, especially in the chariot race. In this case, however, Achilles himself does not participate in the athletic events of the Funeral Games for Patroklos: it is the other surviving Achaean heroes of the Iliad who serve as prototypical participants in the athletic events, while Achilles himself simply presides over these events as if he were already dead, having already achieved the status of the cult hero who will be buried in the sēma ‘tomb’ to be shared with his other self, Patroklos. [13]

So we have seen that the Black Figure paintings on the Boston Hydria and on the Münster Hydria are both referring to a specific context, that is, to the festival of the Panathenaia in Athens around 510 BCE, featuring the athletic event of the apobatic contest. But we must not forget that this festival also featured an all-important poetic event, that is, competitive rhapsodic recitations of the Homeric Iliad and Odyssey. [14] Just as the Black Figure paintings focus on one single moment in the athletic program of the Panathenaia, so also they are focusing on one single moment in the poetic program of the same festival. That moment is what I have been calling the apobatic moment. At the quadrennial Panathenaic festival held in the year 510 BCE (and the same could be said about the earlier festivals of 514 BCE and before, or about the later festivals of 506 BCE and thereafter), the version of the Iliad that was performed in that era must have featured the same apobatic moment that was featured in the Black Figure paintings that art historians date around 510 BCE. It is the moment when the apobatēs steps off his chariot and runs the rest of the course on foot. The killer instinct of the fired-up athlete may now run itself out in the full course of his run.

This is also the apobatic moment in the Iliad when Achilles steps off his chariot and keeps on running until his fury finally runs out. Then he may finally engage with the feeling of pity – and re-engage with his own humanity.

Such a version of the Iliad, I argue, was current in the era when the Boston Hydria and the Münster Hydria were painted. It was in this era when the poetic program of the Panathenaia was being reformed by the tyrant Hipparkhos, son of Peisistratos. This Athenian tyrant played a major role in shaping the ultimate form of the Panathenaic Homer, that is, of the Homeric Iliad and Odyssey as we know them. Hipparkhos is credited with having established an Athenian institution we know today as the Panathenaic Regulation, which concerns the performing of the Homeric Iliad and Odyssey at the festival of the Panathenaia. In terms of the Panathenaic Regulation, the Homeric Iliad and Odyssey became the standard epic repertoire of the quadrennial Panathenaic festival. The key passage is to be found in “Plato” Hipparkhos (228b-c), where we read what amounts to an aetiology of the Panathenaic Regulation. As I have argued elsewhere, the custom of relay-performing the Iliad and Odyssey in sequence at the festival of the Panathenaia is a ritual in and of itself. [15]

Hipparkhos left his mark in defining the festival of the Panathenaia in Athens not only by way of instituting the Panathenaic Regulation. He actually died at the Panathenaia. He was assassinated on the festive quadrennial occasion of the Great Panathenaia that was held in the year 514 BCE, and his spectacular death is vividly memorialized by both Thucydides (1.20.2 and 6.54-59) and Herodotus (5.55-61). Despite the assassination, however, the older brother of Hipparkhos, Hippias, maintained his family’s political control of Athens. Then, in the year 510, he was finally overthrown, and this date marks the end of the “tyranny” of the Peisistratidai, which then gave way to the “democracy” initiated in 508 by Cleisthenes, head of the rival lineage of the Alkmaionidai.

The apobatic moment for Achilles as athlete goes back to this era in the evolution of Homeric poetry as performed at the Panathenaia.

Bibliography

Nagy, G. 1990a. Pindar’s Homer: The Lyric Possession of an Epic Past. Baltimore. Revised paperback version 1994.

—. 1990b. Greek Mythology and Poetics. Ithaca. Revised paperback version 1992.

—. 1999. The Best of the Achaeans: Concepts of the Hero in Archaic Greek Poetry. 2nd ed., with new introduction, Baltimore.

—. 2002. Plato’s Rhapsody and Homer’s Music: The Poetics of the Panathenaic Festival in Classical Athens. Cambridge MA and Athens.

Stähler, K. P. 1967. Grab und Pysche des Patroklos: Ein schwarzfiguriges Vasenbild. Münster i.W.

Vermeule, E. D. T. 1965. “The Vengeance of Achilles: The Dragging of Hektor at Troy.” Bulletin of the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston 63:34-52.

Footnotes

[ ] 4. Dionysius of Halicarnassus Roman Antiquities 7.73.3; Harpocration s.v. In Eratosthenes Catasterismi chapter 1, section 13, lines 19-22, we read that the apobatēs is a re-enactment of the prototypical chariot-fighter (carrying a spear and wearing a three-plumed helmet) who rode next to Erikhthonios as chariot-driver when Erikhthonios founded the festival of the Panathenaia in Athens.

[ ] 6. Dionysius of Halicarnassus Roman Antiquities 7.73.3. According to other sources, the apobatēs can leap on as well as off the platform of a racing chariot: see Etymologicum magnum ed. Kallierges p. 124 lines 31-34 and Photius Lexicon α 2450. Paintings of mythological scenes showing a warrior mounting his chariot may correspond to athletic scenes where the apobatēs mounts his chariot: see Vermeule 1965:44 on the Amphiaraos crater.

[ ] 7. Vermeule and Stähler survey a wide variety of relevant pictures besides the two pictures that concern me primarily here, which are the pictures painted on the Boston Hydria and the Münster Hydria.