Introduction

Part 1: Minoan-Mycenaean civilization and memories of a sea-empire

Introduction

Minoan Empire

Mycenaean Empire

Intermezzo: A word about myth and ritual

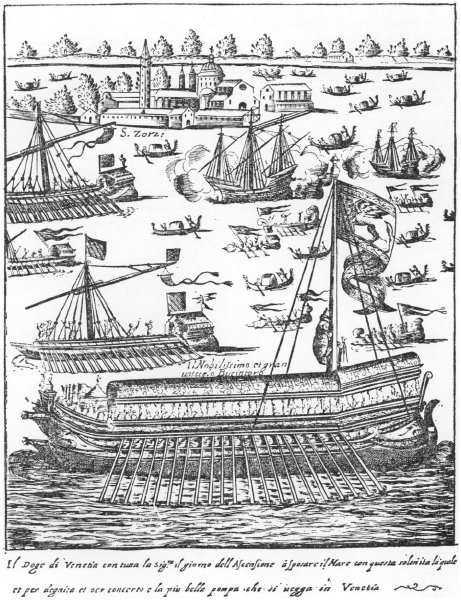

A ritual moment for the sea-empire of Venice

Figure 3. Il Bucintoro at the Molo on Ascension Day, c. 1732. Canaletto [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons.

Figure 4. Il Bucintoro, the Doge’s ship of state, accompanied by a flotilla., c. 1609, Giacomo Franco. [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons. {12|13}

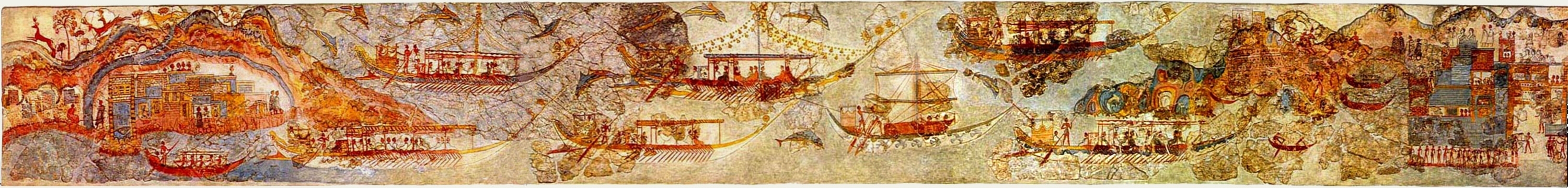

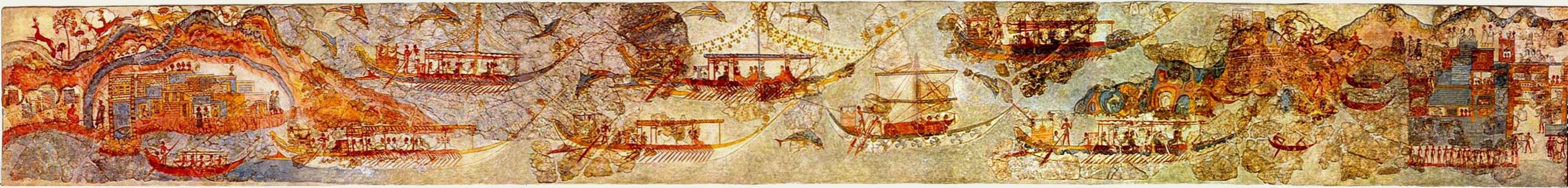

Figure 5. Theran fresco at Akrotiri showing flotilla; c. 1600 BCE, panorama by smial; modified by Luxo, via Wikimedia Commons.

Figure 7. The Doge Sebastiano Ziani disembarking from il Bucintoro at the Convent of Charity. Miniature, 16th Century, [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons.

Flanking the flagship il Bucintoro here, as we can see, are two smaller ships, one in the foreground and one further behind in the background. The doge has already disembarked, and he proceeds to give his respects to the pope. [23]

https:

Figure 9. Bishop of Ravenna throws a ring into the Adriatic Sea as part of lo Sposalizio del Mare, via http://www.romagnaforyou.it. [Note: at the time of publication this website was compromised by malware. The hyperlink has been disabled.]

A mythological moment for the sea-empire of Athens

Part 2: Looking through rose-colored glasses while sailing on a sacred journey

Introduction

The sacred sea-voyage of Theseus

Some thoughts about the terms myth and ritual

To say it another way:

So, myth is an optional aspect of ritual. And myth operates within the larger framework of ritual. [33] Further, as a framework for myth, a ritual can imply a myth even if that myth is not explicitly retold each and every time the ritual is reperformed.

Transition: A ritual moment as represented in a painting

The “flotilla scene”

Figure 11. Detail from Theran fresco at Akrotiri, c. 1600 BCE, original image via Wikimedia Commons.

A ritual moment for the Aegean sea-empire

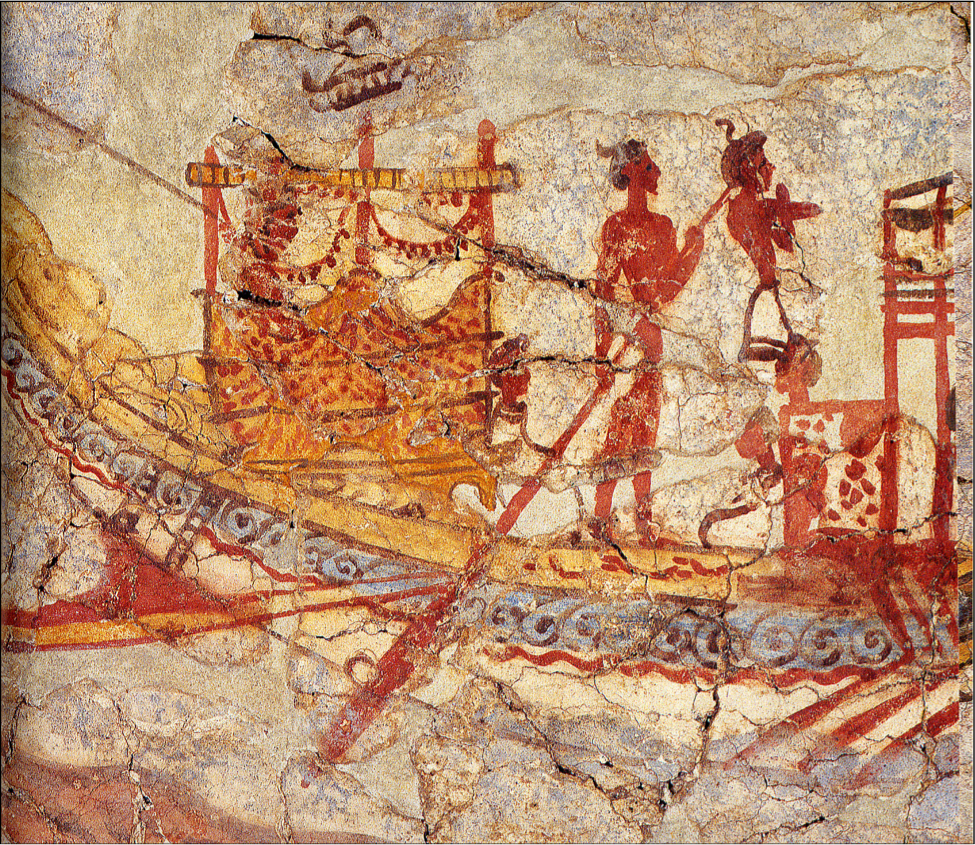

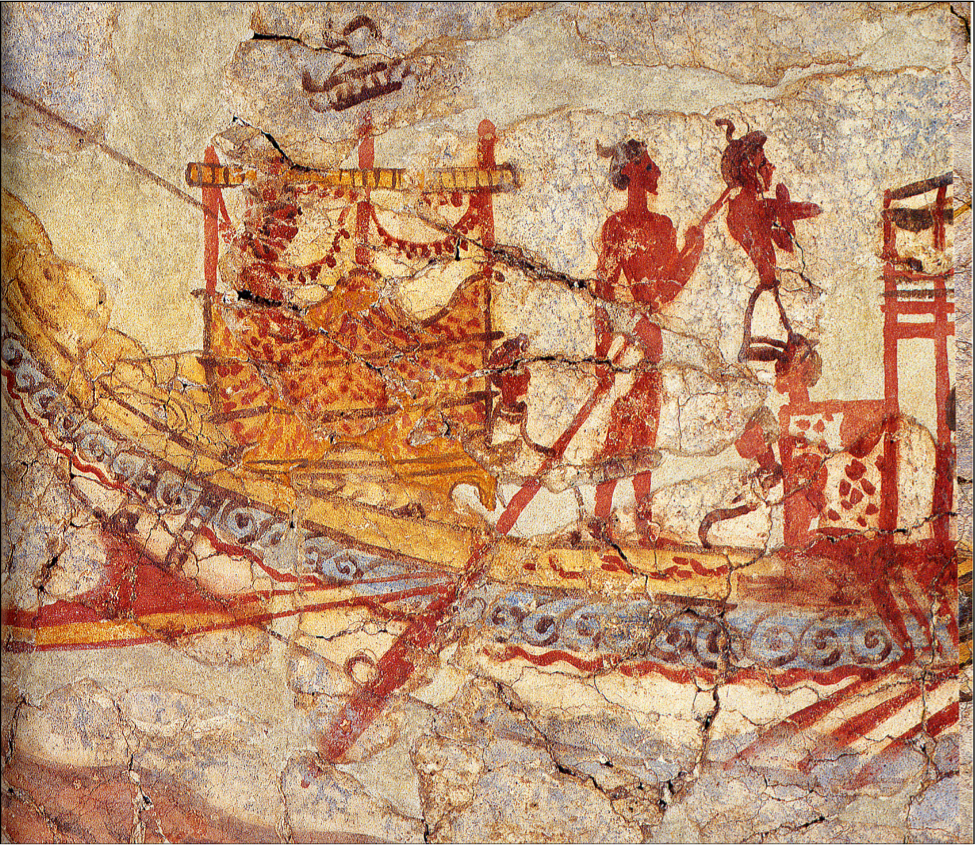

Figure 12. Detail from a fresco painting in Room 4 of the West House.

For an interpretation of this picture, I repeat, with adjustments to the present argument, what I say in my book The Ancient Greek Hero in 24 Hours: [45]

Figure 13. This picture, sent to me by my friend Costas Tzagarakis, shows an assortment of garlands on sale in a marketplace. The flowers that make up the garland in this case are sempreviva (in Venetian Italian, it means ‘eternally alive’; the local Greeks think it is a local Greek word). The locale is Cythera. For more on this flower and on its symbolism, I refer here to Tzagarakis 2011.07.29. {25|26}

Figure 14. A votive offering or tama, showing stephana or ‘wedding garlands’.

Figure 15. Another votive offering or tama, showing stephana or ‘wedding garlands’.

Part 3: From Athens to Crete and back

Introduction

A missing link: The Athenian connection

What is missing so far in the big picture?

Figure 16. From a fresco found at Hagia Triadha in Crete. Reconstruction by Mark Cameron, p. 96 of the catalogue Fresco: A Passport into the Past, 1999 (for an expanded citation, see the Bibliography below). Reproduced with the permission of the British School at Athens. BSA Archive: Mark Cameron Personal Papers: CAM 1.

Part 4: A Cretan Odyssey, Phase I

Introduction

Minoan-Mycenaean Crete as viewed in the Odyssey

Amnisos : Eleuthiāi meli [followed by the ideogram for “amphora”] 1

‘Amnisos: for Eleuthia, honey, one amphora’

Cherchez la femme

Figure 17. Detail from a fresco found at Hagia Triadha in Crete. Reconstruction by Mark Cameron, p. 96 of the catalogue Fresco: A Passport into the Past, 1999 (for an expanded citation, see the Bibliography below). Reproduced with the permission of the British School at Athens. BSA Archive: Mark Cameron Personal Papers: CAM 1.

Part 5: A Cretan Odyssey, Phase II

Introduction

Ariadne and her garland

More on Ariadne and Theseus

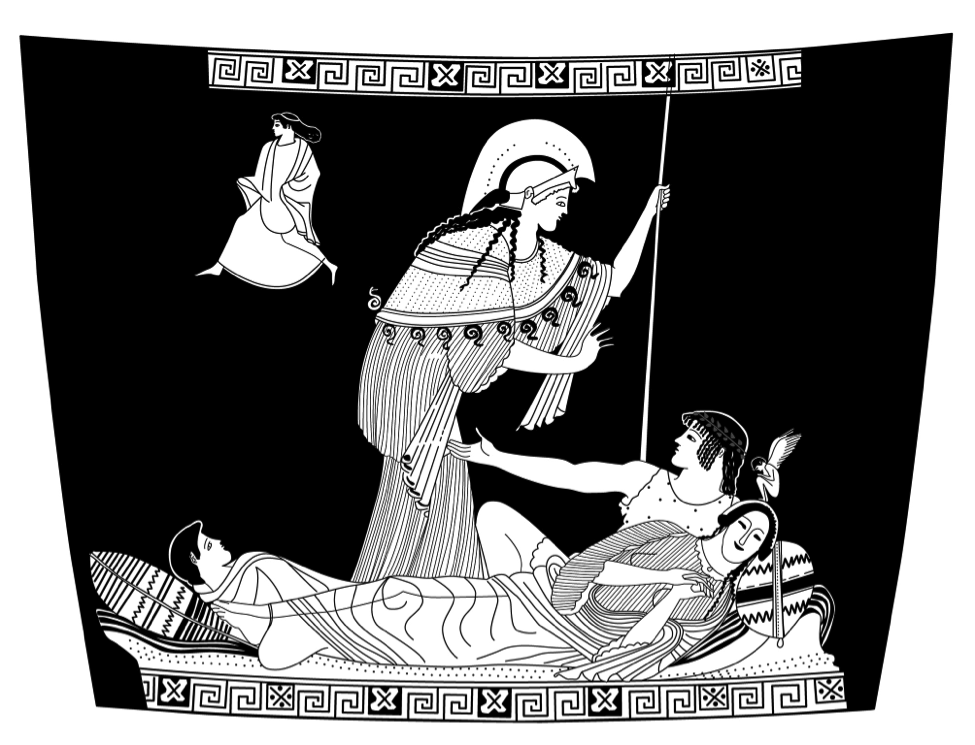

Figure 18. Painting on a lekythos attributed to the Pan Painter, dated around 470 BCE (Taranto IG 4545). The line drawing, presented in rollout mode, is by Tina Ross.

Recalling the blond hair of Ariadne

The Athenian connection revisited

The occlusion of Ariadne

The occlusion of Minoan thalassocracy

The occlusion of Minoan thalassocracy in the Odyssey

I say solemnly that I was born and raised in Crete, the place that reaches far and wide

A Spartan variation on a Minoan-Mycenaean theme

How the telling of Cretan Tales begins only after the sojourn with the Phaeacians

A Cretan adventure as an alternative to a Spartan adventure

I [= Athena] will convey him [= Telemachus] on his way to Sparta and to sandy Pylos

κεῖθεν δὲ Σπάρτηνδε παρὰ ξανθὸν Μενέλαον·

ὃς γὰρ δεύτατος ἦλθεν Ἀχαιῶν χαλκοχιτώνων.

First you [= Telemachus] go to Pylos and ask radiant Nestor

and then from there to Sparta and to golden-haired Menelaos,

the one who was the last of the Achaeans, wearers of bronze tunics, to come back home.

I [= Athena] will convey him [= Telemachus] on his way to Crete and to sandy Pylos

πρῶτα μὲν ἐς Πύλον ἐλθὲ, …

κεῖθεν δ’ ἐς Κρήτην τε παρ’ Ἰδομενῆα ἄνακτα,

ὃς γὰρ δεύτατος ἦλθεν Ἀχαιῶν χαλκοχιτώνων.

First go to Pylos …

and then from there to Crete and to king Idomeneus

who was the last of the Achaeans, wearers of bronze tunics, to come back home.

Cretan adventures of Odysseus

Occluding the Cretan heritage of Homeric poetry

This poet of yours [= this poet who belongs to you Athenians] seems to have been quite sophisticated [kharieis].