This formulation has a converse. Whereas the sacred includes the profane in festive situations, it can be expected to exclude the profane in non-festive situations. That is, in non-festive situations the sacred is marked and the profane is unmarked. Only in festive situations does the sacred become the unmarked member in its opposition with the profane. Only in festive situations does the sacred include the profane. Once the festival is over, the sacred can once again wall itself off from the profane.

You with strands of hair in violet, O holy [(h)agna] one, you with the honey-sweet smile, O Sappho!

As I argued in earlier work, the wording that describes the choral figure of Sappho here is fit for a queenly goddess. [38] For example, the epithet (h)agna ‘holy’ is elsewhere applied to the goddess Athena (Alcaeus F 298.17) and to the Kharites ‘Graces’ as goddesses (Sappho F 53.1, 103.8; Alcaeus F 386.1). As for the epithet ioplokos ‘with strands of hair in violet’, it is elsewhere applied as a generic epithet to the Muses themselves (Bacchylides 3.17). In the overall context of all her songs identifying her with Aphrodite herself, Sappho appears here as the very picture of that goddess.

αἰδώς,

αἰ δ’ ἦχες ἐσθλῶν ἵμερον ἢ καλῶν

καὶ μή τι εἰπῆν γλῶσσ’ ἐκύκα κακόν

αἰδώς κέν σε οὐκ εἶχεν ὄμματ’,

ἀλλ’ ἔλεγες περὶ τῶ δικαίω.

shame [aidōs] …

{She:}But if you had a desire for good and beautiful things

and if your tongue were not stirring up something bad to say,

then shame would not seize your eyes

and you would be speaking about the just and honorable thing to do.

The meter of the lines in this passage is typical of a pattern found in the songs of Alcaeus:

- “… that the first part of the quotation […] comes from a poem by Alcaeus; the remainder […] from Sappho’s rejoinder.” [42]

- “… that the quotations in Aristotle come from a poem composed by Sappho in the form of a dialogue between herself and Alcaeus.” [43]

Either way we take it, “some have objected that, since Sappho appears to presuppose that her audience is aware of Alcaeus’ words […], it is hard to conceive of any but artificial arrangements for the presentation of the two poems to the public: were both presented, each by its own poet, to the same audience on different occasions?” [44]

Pretty woman, the kind I’d like to meet

Pretty woman, I don’t believe you

You’re not the truth

No one could look as good as you

Mercy

Pretty woman, won’t you pardon me

Pretty woman, I couldn’t help but see

Pretty woman, and you look lovely as can be

Are you lonely just like me?

… rrr …

Pretty woman, stop a while

Pretty woman, talk a while

Pretty woman, give your smile to me

Pretty woman, yeah, yeah, yeah

Pretty woman, look my way

Pretty woman, say you’ll stay with me

Cause I need you

I’ll treat you right

Come with me baby

Be mine tonight

Pretty woman, don’t walk on by

Pretty woman, don’t make me cry

Pretty woman, don’t walk away

OK

{222|223}

If that’s the way it must be, OK

I guess I’ll go on home, it’s late

There’ll be tomorrow night

But wait, what do I see?

Is she walking back to me?

Yeah, she’s walking back to me

O-oh

Pretty woman.

Since the voice of the pretty woman who is ‘walkin down the street’ is not heard in response, her character is in question. When the ‘I’ tells this woman that she is ‘the kind I’d like to meet’, does that wording make her the perfect woman or just a streetwalker who is ‘walkin down the street’—or both? In the beginning, the pretty woman is idealized. She looks too good to be true: ‘I don’t believe you | You’re not the truth | No one could look as good as you’. Words fail to express fully her loveliness: ‘you look lovely as can be’. But, despite all these worshipful words of admiration for the pretty woman, she is in danger of becoming a profanity by the time the song reaches the end: the streetwalker ‘walkin down the street’ who has been implored not to ‘walk on by’ but to ‘stop a while’ and to ‘talk a while’ will now be seen in the act of ‘walkin back to me’. And her character can be called into question precisely because she is about to come into contact with the questionable character of the ‘I’ who is singing to her. The ‘I’ had started reverently enough by addressing the pretty woman in the mode of a worshipful admirer. And, for a while, the wording continued to be reverent, but then the undertone of irreverence set in. The cry of ‘Mercy’ at the end of the first stanza already sounds less like an admiring exclamation and more like a predatory growl, which then devolves further into a non-verbal ‘…rrr…’ at the end of the second stanza. By now the sound resembles the mating call of a tomcat on the prowl.

- (a) “A poem by two writers is hard to imagine in the sixth century.” [49]

- (b) “Aristotle’s text […] implies either two poems by two writers or one poem (in dialogue-form) by one writer.” [50]

The theatricality stays blurred even if one “writer”—either Alcaeus or Sappho—is imagined as the composer of a functioning dialogue. Those who choose to imagine such a writer need to impose restrictions, as we see in the argument “that the poem is not a dialogue between Alcaeus and Sappho but between a man and a woman, or rather between a suitor and a rather unwelcoming maiden.” [51] In other words, a dialogue between would-be lovers seems imaginable only if neither Alcaeus nor Sappho is participating in the dialogue. It is assumed that Alcaeus and Sappho could not represent Sappho and Alcaeus respectively in such dialogic roles. After all, these figures are the equivalent of what we think is a writer. Surely a writer cannot be transformed into some kind of singing actor!

Even when a composer is speaking in his or her own persona, the reperformance of the speaking ‘I’ in a symposium can lead to a fragmentation of this persona:

There is a parallel fragmentation of the persona of Alcaeus. Didymus, an eminent philologist in the late first century BCE who followed the methodology of Aristarchus, attempts to distinguish Alcaeus the poet from an Alcaeus who is merely a lyre-player (scholia to Aristophanes Women at the Thesmophoria 162). Further, Quintilian (Principles of Oratory 10.1.63) says he is puzzled that Alcaeus the poet mixes high-minded statesmanship with frivolous love affairs.

Σαπφοῦς φορμίζων ἱμερόεντα πόθον

γινώσκεις

How many ensembles of comastic singers [kōmoi] did Alcaeus of Lesbos greet [61] {229|230}

as he played out on his lyre a yearning [pothos]—lovely [62] it was—for Sappho

– you know how many (such ensembles) there were.

This testimony, by way of Hermesianax of Colophon (early third century BCE), indicates that Alcaeus was well known for singing not one but many love songs that were directed at Sappho—and that were performed in the Dionysiac context of the kōmos.

βάλλων χρυσοκόμης Ἔρως

νήνι ποικιλοσαμβάλῳ

συμπαίζειν προκαλεῖται.

ἣ δ’ (ἐστὶν γὰρ ἀπ’ εὐκτίτου

Λέσβου) τὴν μὲν ἐμὴν κόμην

(λευκὴ γάρ) καταμέμφεται,

πρὸς δ’ ἄλλην τινὰ χάσκει.

ὕμνον, ἐκ τᾶς καλλιγύναικος ἐσθλᾶς

Τήιος χώρας ὃν ἄειδε τερπνῶς

πρέσβυς ἀγαυός.

– it was thrown by the one with the golden head of hair, Eros,

and—with a young girl wearing pattern-woven sandals

– to play with her does he [= Eros] call on me.

But, you see, she is from that place so well settled by settlers,

Lesbos it is. And my head of hair,

you see, it’s white, she finds fault with it.

And she gapes at something else—some girl.

that particular humnos. It came from the noble place of beautiful women, {231|232}

and the man from Teos sang it. It came from that space. And, as he sang, he did so delightfully,

that splendid old man.

In the context of a learned claim about an ostensible mistake on the part of Hermesianax, we see here another learned claim about another ostensible mistake—this time on the part of Chamaeleon of Heraclea Pontica (fourth / third centuries BCE). In his work On Sappho (F 26 ed. Wehrli), Chamaeleon interpreted what we know as Song 358 of Anacreon to be the words of the poet’s declaration of love for Sappho.

The vase on which this image was painted, now housed in Munich, was discovered in the vicinity of the ancient site of Akragas in Sicily (as of 1823, this vase was recorded as part of the Panitteri collection in Agrigento). [68] As we will now see, the place of discovery is significant.

Bell shows that both the painted vase and the marble sculpture were custom-made by Athenian artisans sometime in the decade of 480–470 BCE, and that both of these artifacts had been commissioned as artistic trophies intended for members of the dynastic family of the Emmenidai in Akragas—most likely for Xenokrates, tyrant of Akragas, and for Thrasyboulos, his son. [72] How the vase survived is not known. As for the sculpture, the fact that it was found on the island of Motya leaves some clues. When Carthaginian forces captured and pillaged Akragas in 406 BCE, the statue was evidently carried off to this island; as Bell notes, “this may have been the moment when the face and genitals of the sculpture were intentionally damaged.” [73]

(= εἰμὶ κωμάζων ὑπ’ αὐ[λοῦ])

I am celebrating in a kōmos to the accompaniment of an aulos. [99]

There is a conclusion to be drawn from this picture: whenever you are celebrating in a kōmos, you sing and dance to the tune of an aulos even if a barbiton is literally at hand.

A moment ago, I described as an Aphrodisiac effect the ritual symbolism inherent in the undoing of a woman’s hair, and my prime example was the eroticized image of Andromache’s completely loosened hair. In what follows, we will see that such a description applies also to the eroticized image of Sappho’s partially loosened hair as depicted by the painter of the Munich vase.

In this paraphrase of Sappho’s song, the reference to the agōnes ‘contests’ in which she supposedly competes seems to be a playful anachronistic allusion to the monodic competitions of kithara-singers at the festival of the Panathenaia. It is as if Sappho herself were a monodic singer engaged in such public competitions. But the ongoing paraphrase of the song reveals the older choral setting of that song. And the detail about Aphrodite’s loose strands of flowing hair as pictured by Sappho’s song and as repictured by the paraphrase of Himerius is evidently part of the choral lyric repertoire. [121]

σπεύδοντά τ’ ἀσπούδαστα, Πενθέα λέγω,

ἔξιθι πάροιθε δωμάτων, ὄφθητί μοι,

915σκευὴν γυναικὸς μαινάδος βάκχης ἔχων,

μητρός τε τῆς σῆς καὶ λόχου κατάσκοπος·

πρέπεις δὲ Κάδμου θυγατέρων μορφὴν μιᾶι.

…

925{Πε.} τί φαίνομαι δῆτ’; οὐχὶ τὴν Ἰνοῦς στάσιν

ἢ τὴν Ἀγαυῆς ἑστάναι, μητρός γ’ ἐμῆς;

{Δι.} αὐτὰς ἐκείνας εἰσορᾶν δοκῶ σ’ ὁρῶν.

ἀλλ’ ἐξ ἕδρας σοι πλόκαμος ἐξέστηχ’ ὅδε,

οὐχ ὡς ἐγώ νιν ὑπὸ μίτραι καθήρμοσα.

930{Πε.} ἔνδον προσείων αὐτὸν ἀνασείων τ’ ἐγὼ

καὶ βακχιάζων ἐξ ἕδρας μεθώρμισα.

{Δι.} ἀλλ’ αὐτὸν ἡμεῖς, οἷς σε θεραπεύειν μέλει,

πάλιν καταστελοῦμεν· ἀλλ’ ὄρθου κάρα.

{Πε.} ἰδού, σὺ κόσμει· σοὶ γὰρ ἀνακείμεσθα δή.

935{Δι.} ζῶναί τέ σοι χαλῶσι κοὐχ ἑξῆς πέπλων

στολίδες ὑπὸ σφυροῖσι τείνουσιν σέθεν.

{Πε.} κἀμοὶ δοκοῦσι παρά γε δεξιὸν πόδα·

τἀνθένδε δ’ ὀρθῶς παρὰ τένοντ’ ἔχει πέπλος.

{Δι.} ἦ πού με τῶν σῶν πρῶτον ἡγήσηι φίλων,

940ὅταν παρὰ λόγον σώφρονας βάκχας ἴδηις.

{Πε.} πότερα δὲ θύρσον δεξιᾶι λαβὼν χερὶ

ἢ τῆιδε βάκχηι μᾶλλον εἰκασθήσομαι;

{Δι.} ἐν δεξιᾶι χρὴ χἄμα δεξιῶι ποδὶ

αἴρειν νιν· αἰνῶ δ’ ὅτι μεθέστηκας φρενῶν. {253|254}

{Dionysus:}

You there! Yes, I’m talking to you, to the one who is so eager to see the things that should not be seen

and who hurries to accomplish things that cannot be hurried. I’m talking to you, Pentheus.

Come out from inside the palace. Let me have a good look at you

915wearing the costume of a woman who is a Maenad Bacchant,

spying on your mother and her company.

The way you are shaped, you look just like one of the daughters of Kadmos.

[…]

925{Pentheus:}

So how do I look? Don’t I strike the dancing pose [stasis] of Ino

or the pose struck by my mother Agaue?

{Dionysus:}

Looking at you I think I see them right now.

Oh, but look: this strand of hair [plokamos] here is out of place. It stands out,

not the way I had secured it underneath the headband [mitra].

{Pentheus:}

While I was inside, I was shaking it [= the strand of hair] forward and backward,

and, in the Bacchic spirit, I displaced it [= the strand of hair], moving it out of place.

{Dionysus:}

Then I, whose concern it is to attend to you, will

arrange it [= the strand of hair] all over again. Come on, hold your head straight. [123]

{Pentheus:}

You see it [= the strand of hair]? There it is! You arrange [kosmeîn] it for me. I can see I’m really depending on you.

{Dionysus:}

And your waistband has come loose. And those things are not in the right order. I mean, the pleats of your peplos, the way they

extend down around your ankles.

{Pentheus:}

That’s the way I see it from my angle as well. At least, that’s the way it is down around my right foot,

but, on this other side, the peplos does extend in a straight line down around the calf. [124]

{Di.} I really do think you will consider me the foremost among those dear to you

when, contrary to your expectations, you see the Bacchants in full control of themselves [= sōphrones].

{Pentheus:}

So which will it be? I mean, shall I hold the thyrsus with my right hand

or with this other one? Which is the way I will look more like a Bacchant?

{Dionysus:}

You must hold it in your right hand and, at the same time, with your right foot {254|255}

you must make an upward motion. I approve of the way you have shifted in your thinking.

The image of hair displaced in the process of Bacchic dancing recurs elsewhere in the Bacchae (150, 455–456). [126] Of special interest is the use of pothos ‘desire’ in such contexts (456; also at 415). Elsewhere (693–713), we see the Bacchants shifting from a state of ‘proper arrangement’ or eukosmia (693) to a state of full Bacchic possession, the first sign of which is that they let their hair down to their shoulders (695). [127] As we know from the words of instruction uttered by Dionysus himself to Pentheus (830–833), the initial kosmos ‘arrangement’ (832) of the Bacchant includes these two requirements: {1} flowing long hair (831) that is done up and arranged by way of the mitra ‘headband’ (833) and {2} an ankle-length peplos (833). [128]

Next I turn to a complementary working definition of ritual, again from Burkert:

In my own work, I have applied these definitions for the purpose of analyzing the interaction of myth and ritual in traditional song, dance, and instrumental accompaniment. [136] I have also applied to this analysis a concept developed by the anthropologist Stanley Tambiah in his typological studies of ritual: he describes what he calls a “fusion of experience” in ritual, produced by “the hyper-regular surface structure of ritual language.” [137] Tambiah’s understanding of ritual language accommodates all aspects of what I have just described as song, dance, and instrumental accompaniment. [138] As for Tambiah’s concept of fusion, it corresponds to what Burkert describes as the solidarity of participants in ritual. [139] In particular, as I argued, this concept of fusion corresponds to ritual participation in the mimēsis of myth by the ritual ensemble that we know as the khoros ‘chorus’. [140] {261|262}

(Although Tambiah speaks only of male participants in ritual, his formulations can of course extend to female participants as well.) In terms of my analysis of the Dionysiac effect, I offer two relevant examples. Both involve participants in the rituals of Dionysus. One is a positive example while the other is negative. To start with the negative, I point to the mythical figure of Pentheus in the Bacchae of Euripides: he fits perfectly Tambiah’s model of “those who resist yielding to this constraining influence.” As for a positive example, I point to the mythical figure of the Maenad facing Dionysus in the picture painted on the Munich vase: she fits perfectly the model of a participant in ritual who feels a “constraint” acting upon her and inducing in her, when she yields to it, “the pleasure of self-surrender.”

Images

Image 1: Attic krater attributed to the Brygos painter, 480-470 BCE. Line drawing by Valerie Woelfel.{264|265}

Image 2: Attic krater attributed to the Brygos painter, 480-470 BCE. Line drawing by Valerie Woelfel.

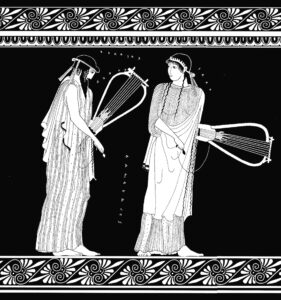

Image A: Attic kalyx-krater attributed to the Tithonos Painter, first third of the fifth century. Line drawing by Valerie Woelfel.

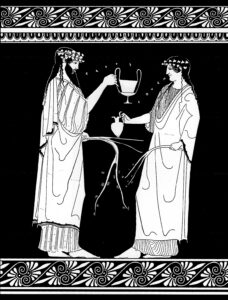

Image B: Attic kalyx-krater attributed to the Tithonos Painter, first third of the fifth century. Line drawing by Valerie Woelfel.