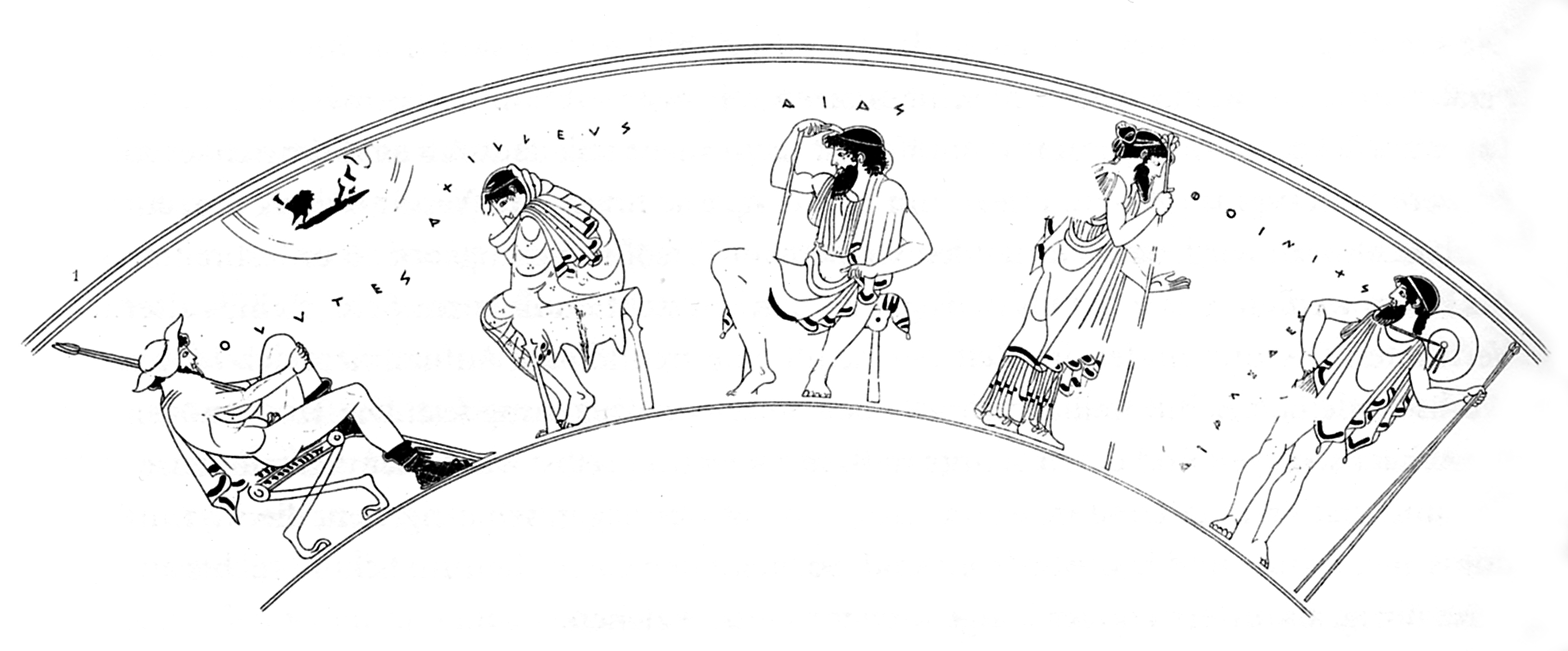

- Athenian red-figure aryballos, Berlin Antikensammlung F2326/LIMC 443 (s.v. Achilleus) Embassy to Achilles — Odysseus, Achilles, Ajax, Phoinix, Diomedes (here Plate 1)

- Boeotian black-figure pelike (miniature, 7 cm in height), Berlin Antikensammlung F2121/LIMC 455 (Plate 2)

- Athenian red-figure hydria, Staatliche Antikensammlung, München 8770/LIMC 445Phoinix, Odysseus, Achilles, youth, attributed to Kleophrades Painter (Plate 3)

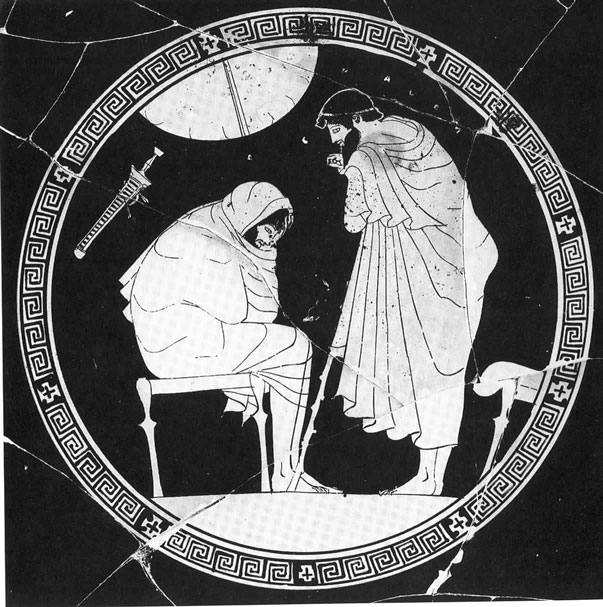

- Athenian red-figure cup, British Museum E56/LIMC 444, Achilles and Odysseus, attributed to Douris or the Oedipus Painter (Plate 4)

- Athenian red-figure cup, British Museum E76/LIMC 1=14 (s.v. Briseis), Achilles in shelter, Briseis being led away, eponymous vase of the Briseis Painter (Plate 5)

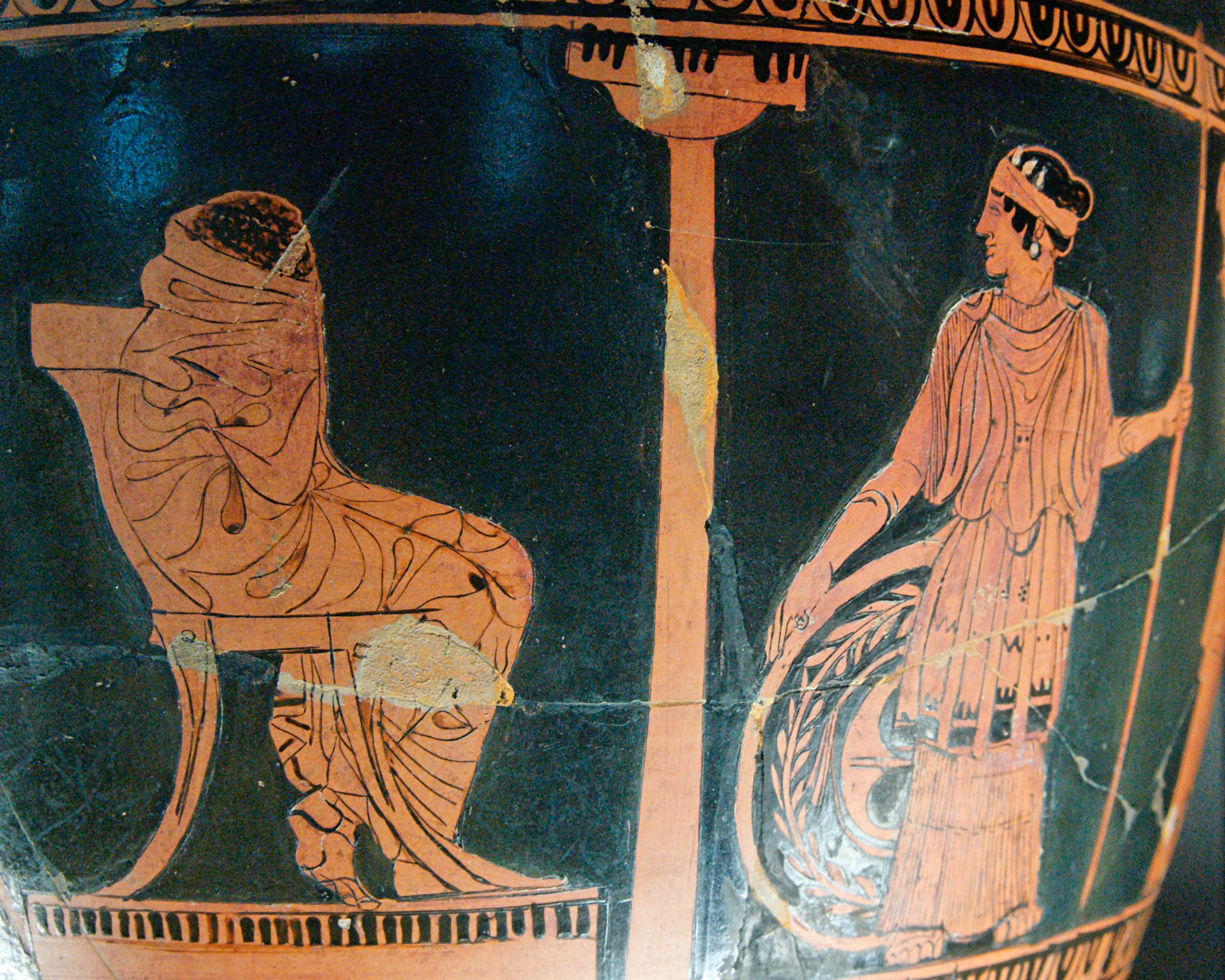

- Athenian red-figure volute crater Louvre G482/LIMC 521, Achilles and Thetis with armor, attributed to Geneva Painter (Plate 6)

- Athenian red-figure pelike, British Museum E363/LIMC 515, Achilles, Thetis, Nereids with armor, attributed by Beazley to Early Mannerist (Plate 7).

Modern scholarship has not produced a consensus on these representations of Achilles. There are two inextricably related points at issue: 1) what does the seated, more or less covered image of Achilles in these images signify? and 2) what is the origin of this way of representing the hero? Rather than resume the whole history of the responses to these questions, I will discuss a few representative recent views on these points in order to expose the difficulties that answering them entails and to propose a new set of answers to them.

Ἀχιλλέα τιν’ ἢ Νιόβην, τὸ πρόσωπον οὐχὶ δεικνύς,

πρόσχημα τῆς τραγῳδίας, γρύζοντας οὐδὲ τουτί.

First he’d sit someone down all covered up,

an Achilles or a Niobe, not showing their face/mask,

a cover-up of a tragedy, without them uttering even so much as ‘this.’

It is Euripides speaking, in the agon of the Frogs, satirizing Aeschylus’ dramatic technique. The Aristophanic scholia tell us that Euripides is alluding, in the case of Achilles, to Aeschylus’ Phrygians, also known as the Ransom of Hector, with one of the scholia recentiora suggesting that it may also refer to the Myrmidons, but since the 19th Century, scholars have made the case that it is in fact the Myrmidons that Aristophanes had in mind; Myrmidons is a play mentioned elsewhere in the Frogs. That view was strongly argued by Bernhard Döhle in 1967 and Oliver Taplin in 1972 on the basis of the fragments and the vase paintings in the case of Döhle and on the basis of still more fragments of the play in the case of Taplin, who leaves the evidence of the vases to Döhle. [3] Although there is evidence that Achilles, like Niobe, appeared on stage for long periods as a silent, seated figure in both plays, the Phrygians seems to have actually begun with a scene in which the grieving Achilles spoke to Hermes to give his assent to the ransom of Hector, which would contradict the πρώτιστα in line 911 of the Aristophanic Euripides’s words. And there are also other details that match Myrmidons better than Phrygians, according to Taplin.

στήθεσσιν λασίοισι διάνδιχα μερμήριξεν,

ἢ ὅ γε φάσγανον ὀξὺ ἐρυσσάμενος παρὰ μηροῦ

τοὺς μὲν ἀναστήσειεν, ὃ δ’ Ἀτρεΐδην ἐναρίζοι,

ἦε χόλον παύσειεν ἐρητύσειέ τε θυμόν.

So he spoke. Anguish [akhos] came over the son Peleus, and his heart within

his hairy chest was divided

whether he should draw his sharp sword from alongside his thigh,

make the rest scatter, and slay the son of Atreus,

or whether he should check his fury [kholos] and restrain his heart [thumos].

Here is another example, not cited by Cairns:

ᾧ ῥά θ᾿ ὑπὸ σκύμνους ἐλαφηβόλος ἁρπάσῃ ἀνὴρ

ὕλης ἐκ πυκινῆς· ὁ δέ τ᾿ ἄχνυται ὕστερος ἐλθών,

πολλὰ δέ τ᾿ ἄγκε᾿ ἐπῆλθε μετ᾿ ἀνέρος ἴχνι᾿ ἐρευνῶν,

εἴ ποθεν ἐξεύροι· μάλα γὰρ δριμὺς χόλος αἱρεῖ·

ὣς ὁ βαρὺ στενάχων μετεφώνεε Μυρμιδόνεσσιν·

groaning really intensely, like a lion with a great mane

whose cubs a deerhunter steals out from under his protection,

from a dense wood; and the lion grieves when he returns later,

and he ranges over many mountain dells, tracking the man’s traces,

in the hope that he may find him somewhere, for really bitter anger seizes him;

groaning deeply like him, he spoke among the Myrmidons:

The subject of this simile is Achilles himself, and he is grieving for Patroclus. My point for the moment is that akhos and kholos are separate emotions, not overlapping ones, as Cairns would have it. The lion’s grief at the loss of his cubs leads to his determined search for the hunter who seized them, which is motivated by his anger. But the grief does not go away, and the poet uses the comparison as a parallel between those in grief, not anger, though the anger will come later. Although they often constitute a sequence, akhos can remain as is. That is why Paris can explain to Hector what motivated his withdrawal with these words:

ἥμην ἐν θαλάμῳ, ἔθελον δ᾿ ἄχεϊ προτραπέσθαι.

Not so much with anger at the Trojans or even with indignation

was I sitting in the bedroom, but I wanted to give myself up to akhos.

He makes clear that his akhos has not become kholos. To say that the regularity of this sequence implies an overlap in meaning between the two, as Cairns does, is to confuse the syntax of these emotions with their semantics. It is appropriate to say that akhos can bring on kholos, but not appropriate to say that akhos actually is kholos. So also with the gesture of veiling. I would suggest that it marks the grief or pain of the person, male or female, who is veiled, and that grief can modulate into anger or remain as grief. So Demeter, who is actually called Ἀχαιά in the context of her akhos over the descent into the underworld of Kore, and who takes on a black veil, also has mēnis in the Homeric Hymn. [13] The veil itself does not betoken the anger, but rather the grief at the loss of her daughter to the lord of the underworld, a grief that entails the possibility of consequent anger. We can see this same set of steps in the one example that Cairns has found in which there is no explicit grief before the anger, in the messenger speech from Euripides’ Medea 1144-1155:

πρὶν μὲν τέκνων σῶν εἰσιδεῖν ξυνωρίδα,

πρόθυμον εἶχ’ ὀφθαλμὸν εἰς Ἰάσονα

ἔπειτα μέντοι προυκαλύψατ’ ὄμματα

λευκήν τ’ ἀπέστρεψ’ ἔμπαλιν παρηίδα,

παίδων μυσαχθεῖσ’ εἰσόδους. πόσις δὲ σὸς

ὀργάς τ’ ἀφῄρει καὶ χόλον νεάνιδος,

λέγων τάδ’· Οὐ μὴ δυσμενὴς ἔσῃ φίλοις,

παύσηι δὲ θυμοῦ καὶ πάλιν στρέψεις κάρα,

φίλους νομίζουσ’ οὕσπερ ἂν πόσις σέθεν,

δέξῃ δὲ δῶρα καὶ παραιτήσῃ πατρὸς

φυγὰς ἀφεῖναι παισὶ τοῖσδ’ ἐμὴν χάριν;

before she looked upon your two children

was training an eager eye upon Jason,

but then she veiled her eyes

and turned back away her white cheek

in disgust when the children entered. And your husband

tried to pluck out the pique and anger from the young woman

with these words: You will not be hostile to those who are dear,

and will you cease from anger and turn back your head,

thinking dear those whom your husband thinks dear,

and will you accept the gifts and request of your father

to let up on exile for these children, for my sake?

I note that Glauke actually makes two gestures — she veils her eyes and then turns away her white cheek in disgust at Jason’s children. So when Jason speaks to her in order to remove her kholos, he tells her ‘you will cease from anger and turn back your head.’ I conclude that the veiling, albeit inexplicitly, marks her immediate distress and grief, but the sideways movement of her cheek, her anger. There is no justification in this passage either for considering the veiling in itself to be a gesture of anger.

πορφύρεον μέγα φᾶρος ἑλὼν χερσὶ στιβαρῇσι

κὰκ κεφαλῆς εἴρυσσε, κάλυψε δὲ καλὰ πρόσωπα·

αἴδετο γὰρ Φαίηκας ὑπ’ ὀφρύσι δάκρυα λείβων.

ἦ τοι ὅτε λήξειεν ἀείδων θεῖος ἀοιδός,

δάκρυ’ ὀμορξάμενος κεφαλῆς ἄπο φᾶρος ἕλεσκε

καὶ δέπας ἀμφικύπελλον ἑλὼν σπείσασκε θεοῖσιν·

αὐτὰρ ὅτ’ ἂψ ἄρχοιτο καὶ ὀτρύνειαν ἀείδειν

Φαιήκων οἱ ἄριστοι, ἐπεὶ τέρποντ’ ἐπέεσσιν,

ἂψ Ὀδυσεὺς κατὰ κρᾶτα καλυψάμενος γοάασκεν.

ἔνθ’ ἄλλους μὲν πάντας ἐλάνθανε δάκρυα λείβων,

Ἀλκίνοος δέ μιν οἶος ἐπεφράσατ’ ἠδ’ ἐνόησεν

ἥμενος ἄγχ’ αὐτοῦ, βαρὺ δὲ στενάχοντος ἄκουσεν.

These things, then, the famous bard was singing; as for Odysseus,

he took his great purple cloak in his mighty hands

and drew it down over his head, and he covered his fair face:

for he was ashamed to be shedding a tear from his eyes before the Phaeaecians.

Indeed, whenever the divine bard stopped singing,

wiping away the tears he took his cloak off his head

and taking a two-handled cup he started pouring a libation to the gods;

And whenever he would begin again and they would urge him to sing,

the best of the Phaeacians, since they were delighting in his epea ,

covering over his head again Odysseus kept on singing a góos .

Then all the others did not notice him shedding a tear,

but Alkinoos alone noticed and perceived it

sitting near him, and he heard him groaning deeply.

Finally, after the last song, which narrated the fall of Troy and Odysseus’ part in it, we get an extended simile about his response to the performance, ending with a reprise of the first description of Odysseus veiling himself:

τήκετο, δάκρυ δ’ ἔδευεν ὑπὸ βλεφάροισι παρειάς.

ὡς δὲ γυνὴ κλαίῃσι φίλον πόσιν ἀμφιπεσοῦσα,

ὅς τε ἑῆς πρόσθεν πόλιος λαῶν τε πέσῃσιν,

ἄστεϊ καὶ τεκέεσσιν ἀμύνων νηλεὲς ἦμαρ·

ἡ μὲν τὸν θνῄσκοντα καὶ ἀσπαίροντα ἰδοῦσα

ἀμφ’ αὐτῷ χυμένη λίγα κωκύει· οἱ δέ τ’ ὄπισθε

κόπτοντες δούρεσσι μετάφρενον ἠδὲ καὶ ὤμους

εἴρερον εἰσανάγουσι, πόνον τ’ ἐχέμεν καὶ ὀϊζύν·

τῆς δ’ ἐλεεινοτάτῳ ἄχεϊ φθινύθουσι παρειαί·

ὣς Ὀδυσεὺς ἐλεεινὸν ὑπ’ ὀφρύσι δάκρυον εἶβεν.

ἔνθ’ ἄλλους μὲν πάντας ἐλάνθανε δάκρυα λείβων,

Ἀλκίνοος δέ μιν οἶος ἐπεφράσατ’ ἠδ’ ἐνόησεν

ἥμενος ἄγχ’ αὐτοῦ, βαρὺ δὲ στενάχοντος ἄκουσεν.

These things, then the famous singer was singing; as for Odysseus,

he was melting away, and a tear was drenching the cheeks below his eyelids.

As a woman laments, throwing herself upon her beloved husband

who falls before his city and his people,

trying to ward off the day without pity for his city and his children;

She watches him dying and breathing hard,

and embracing him she shrieks and shrieks; but behind her

butting her back and shoulders with their spears

they lead her off into slavery, to toil and misery;

her cheeks are wasting away with the most pitiful akhos .

So Odysseus was shedding a pitiful tear.

Then all the others did not notice him shedding a tear,

but Alkinoos alone noticed and perceived it

sitting near him, and he heard him groaning deeply.

What is being illustrated here, and what Odysseus himself is expressing in his lamenting, is the same akhos as the captive woman whose city has fallen along with her husband, and I believe that concept, akhos, is the key to the representation of Achilles on the vases as well. The passage in Phaeacia is in fact a reprise of an earlier moment in the Odyssey, before Telemachus has been formally identified to his hosts in Sparta and before Helen has put nepenthe in their wine. Menelaos recounts his own grief, the ἄχος ἄλαστον ‘unforgettable grief’ as he calls it at 4.109, that he feels above all for Odysseus and that Laertes, Penelope, and Telemachus, whom he left behind as a new-born in his home, must share, at which point the narrator continues:

δάκρυ δ’ ἀπὸ βλεφάρων χαμάδις βάλε πατρὸς ἀκούσας,

χλαῖναν πορφυρέην ἄντ’ ὀφθαλμοῖιν ἀνασχὼν

ἀμφοτέρῃσιν χερσί. νόησε δέ μιν Μενέλαος…

So he spoke, and he (Menelaos) stirred up in him (Telemachus) a longing for góos of his father;

a tear fell to the ground from his eyes when he heard of his father,

as he held up his purple cloak before his eyes

with both of his hands. But Menelaos noticed him…

So we have here almost the same scenario, in which someone speaks of the involvement of a third person who is actually present and cannot keep from weeping — the term is in both cases góos— at words or stories that touch him deeply. This is the veiling of a heroic male that expresses the vain attempt to conceal profound, uncontrollable grief. In fact, as Casey Dué reminds me, this scene is itself a reprise of an even earlier scene at the end of Odyssey 1 in which Penelope appears, veiled and weeping, to speak of her πένθος ἄλαστον — compare the ἄχος ἄλαστον of Menelaos in Odyssey 4.109 — at the song of the bard Phemios about the nostoi of the heroes who went to Troy. She is deeply involved in that subject, but Telemachus, who is as yet disconnected from his father, is dismissive of her grief.

ἄχνυται, οὐδέ τί οἱ δύναμαι χραισμῆσαι ἰοῦσα.

κούρην ἣν ἄρα οἱ γέρας ἔξελον υἷες Ἀχαιῶν,

τὴν ἂψ ἐκ χειρῶν ἕλετο κρείων Ἀγαμέμνων.

ἤτοι ὃ τῆς ἀχέων φρένας ἔφθιεν· αὐτὰρ Ἀχαιοὺς

Τρῶες ἐπὶ πρύμνῃσιν ἐείλεον, οὐδὲ θύραζε

εἴων ἐξιέναι· τὸν δὲ λίσσοντο γέροντες

Ἀργείων, καὶ πολλὰ περικλυτὰ δῶρ’ ὀνόμαζον.

ἔνθ’ αὐτὸς μὲν ἔπειτ’ ἠναίνετο λοιγὸν ἀμῦναι,

αὐτὰρ ὃ Πάτροκλον περὶ μὲν τὰ ἃ τεύχεα ἕσσε,

πέμπε δέ μιν πόλεμον δέ, πολὺν δ’ ἅμα λαὸν ὄπασσε.

πᾶν δ’ ἦμαρ μάρναντο περὶ Σκαιῇσι πύλῃσι·

καί νύ κεν αὐτῆμαρ πόλιν ἔπραθον, εἰ μὴ Ἀπόλλων

πολλὰ κακὰ ῥέξαντα Μενοιτίου ἄλκιμον υἱὸν

ἔκταν’ ἐνὶ προμάχοισι καὶ Ἕκτορι κῦδος ἔδωκε.

τοὔνεκα νῦν τὰ σὰ γούναθ’ ἱκάνομαι, αἴ κ’ ἐθέλῃσθα

υἱεῖ ἐμῷ ὠκυμόρῳ δόμεν ἀσπίδα καὶ τρυφάλειαν

καὶ καλὰς κνημῖδας ἐπισφυρίοις ἀραρυίας

καὶ θώρηχ’· ὃ γὰρ ἦν οἱ ἀπώλεσε πιστὸς ἑταῖρος

Τρωσὶ δαμείς· ὃ δὲ κεῖται ἐπὶ χθονὶ θυμὸν ἀχεύων.

He grieves (ἄχνυται), nor am I able in any way to come and be a defense for him.

The young woman whom the sons of the Akhaioi actually chose for him as his prize of honor,

her great Agamemnon took back for himself from his hands.

In fact, he [Achilles] was withering his mind grieving (ἀχέων) for her; yet the Akhaioi,

the Trojans cornered them around the sterns of their ships, and no way out

were they allowing them; but they beseeched him [Achilles], did the old men

among the Argives, and they counted out many very famous gifts for him.

Then at that point he himself refused to ward off destruction,

but he put his own armor on Patroklos,

and he sent him into battle and gave him a great host to go with him.

All day long they fought around the Left Gates.

And on that very day they would even have sacked the city, except Apollo

acting out many bad things to the stalwart son of Menoitios

killed him in the front ranks and gave the kudos to Hector.

That’s why I come now to your knees [Hephaistos’ knees], if you are willing

to give to my swift-destined son a shield and a helmet

and lovely greaves for his knees fitted with anklets

and a breastplate; for the one that he had, his trusted companion lost it,

overwhelmed he was by the Trojans; and he [Achilles] lies on the ground, grieving [ἀχέων] in his heart.

I note that Thetis can resume Achilles’ story without even a single mention of anger on his part, as against three mentions of him grieving, all with forms derived from the root noun akhos. What I am suggesting is that there was a multiform of the Iliad that highlighted, not the mēnis and kholos of Achilles, as ours does, but rather his akhos, though not to the exclusion of his anger. That tradition has survived for us in the name of Achilles, in passages like Thetis’s speech, where her own akhos on behalf of her son has focused her narrative on his akhos, and also in the vase paintings that portray him as a man of constant sorrow at the key points of his story. Nagy shows that the word akhos consistently implies one’s own suffering or personal involvement in someone else’s suffering, [16] as we saw it did for Odysseus in Phaeacia and Telemachus in Sparta, and that aspect of its meaning, he argues, may also account for the name Ἀχαιοί, a word that designates the λαός which is personally involved in Achilles’ suffering, and whose formation from a word like akhos has parallels in pairs κράτος/κραταιός and ἄλθος/Ἀλθαίη.

τῶν αὖ πεντήκοντα νεῶν ἦν ἀρχὸς Ἀχιλλεύς.

ἀλλ’ οἵ γ’ οὐ πολέμοιο δυσηχέος ἐμνώοντο·

οὐ γὰρ ἔην ὅς τίς σφιν ἐπὶ στίχας ἡγήσαιτο·

κεῖτο γὰρ ἐν νήεσσι ποδάρκης δῖος Ἀχιλλεὺς

κούρης χωόμενος Βρισηΐδος ἠϋκόμοιο,

τὴν ἐκ Λυρνησσοῦ ἐξείλετο πολλὰ μογήσας

Λυρνησσὸν διαπορθήσας καὶ τείχεα Θήβης,

κὰδ δὲ Μύνητ’ ἔβαλεν καὶ Ἐπίστροφον ἐγχεσιμώρους,

υἱέας Εὐηνοῖο Σεληπιάδαο ἄνακτος·

τῆς ὅ γε κεῖτ’ ἀχέων, τάχα δ’ ἀνστήσεσθαι ἔμελλεν.

They were called Myrmidons and Hellenes and Achaeans,

Of whose fifty ships Achilles was captain.

But they were not mindful of ill-sounding war,

since there was no one who would lead them into the ranks,

because swift-footed radiant Achilles lay idle among the ships

angry because of the girl, fair-haired Briseis,

whom he took from Lyrnessos, after much toil,

sacking Lyrnessos and the walls of Thebe,

and he overthrew Munes and Epistrophos, mad spearmen both,

the sons of King Euenos the son of Selepos;

he lay there grieving for her, but soon he was about to rise up.

ἵπποι θ’ οἳ φορέεσκον ἀμύμονα Πηλεΐωνα.

ἀλλ’ ὃ μὲν ἐν νήεσσι κορωνίσι ποντοπόροισι

κεῖτ’ ἀπομηνίσας Ἀγαμέμνονι ποιμένι λαῶν

Ἀτρεΐδῃ· λαοὶ δὲ παρὰ ῥηγμῖνι θαλάσσης

δίσκοισιν τέρποντο καὶ αἰγανέῃσιν ἱέντες

τόξοισίν θ’· ἵπποι δὲ παρ’ ἅρμασιν οἷσιν ἕκαστος

λωτὸν ἐρεπτόμενοι ἐλεόθρεπτόν τε σέλινον

ἕστασαν· ἅρματα δ’ εὖ πεπυκασμένα κεῖτο ἀνάκτων

ἐν κλισίῃς· οἳ δ’ ἀρχὸν ἀρηΐφιλον ποθέοντες

φοίτων ἔνθα καὶ ἔνθα κατὰ στρατὸν οὐδὲ μάχοντο.

[the best warrior was Ajax/] while Achilles had mēnis; since he was by far the best,

and so were the horses that were carrying the blameless son of Peleus.

But he at least beside the curved sea-traversing ships

lay there, enraged at Agamemon, shepherd of the hosts,

the son of Atreus; and his warriors at the sea’s edge

were enjoying throwing the discus and spears

and bows and arrows, and their horses, each beside his own chariot,

munching lotus and marsh-grown celery

stood there; the well-joined chariots of the lords lay

in their shelters, while they, longing for their leader, dear to Ares,

walked here and there amid the army, and they were not fighting.

By contrast with the earlier passage, this one does not mention Briseis or the hero’s grief. Instead, it speaks twice of his mēnis, ascribing it to Agamemnon, and dwelling on the consequences for his idle men and idle horses in the larger camp. So these passages are complementary, but also they reflect precisely the contrast in the presentations of Achilles that I have been speaking of. Small wonder, then, that according to the A scholia, Zenodotus athetized the first passage, not the second.

Bibliography

Plates