Archaeological Finds Associated with the Lawcourts

Jury Selection

Timing of Speeches

Laws

Echinos

Jury Voting

Law Court Locations

Jury Selection

Jury service was restricted to male citizens at least thirty years old, and was never mandatory. At the beginning of each year, a jury panel of 6000 was selected — we do not know how — and sworn in. On any of the 150 to 200 days of the year that the courts were in session, anyone on the jury panel who wanted to serve (and collect jury pay) could report to the lawcourts. The process of assigning jurors to cases differed in various periods. For a detailed description of jury selection and court procedures in three periods of Athenian history, see Alan Boegehold’s Three Court Days.

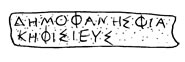

The archaeological finds correspond to the complex jury selection process described by in the Constitution of the Athenians, written sometime in the 320s B.C. In this period, each member of the jury panel was issued a wood or bronze allotment ticket (pinakion) that stated his name, deme, and one of the ten letters from alpha to kappa.

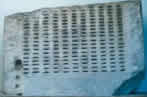

On each court day, the juror tickets were collected and used in conjunction with allotment machines (kleroteria) to select jurors at random.

The stone kleroteria had two sets of five, or one set of ten vertical columns, each of which corresponded to one of the ten letters on the tickets. Tickets were placed in slots below the relevant letter such that the letter, but not the name, was visible. Several black and white balls were dropped into a container attached to a thin tube next to the horizontal rows of tickets. The rows next to black balls were rejected; those next to white balls were selected. The men whose tickets were in the selected rows would serve as jurors on that day.

An additional process of random selection was used to assign each juror to a particular courtroom for the day.

Timing of Speeches

The amount of time allotted to a case differed depending on the seriousness of the charges; trials could be as short as less than half an hour and as long as a full day.

Speaking time was divided evenly between the parties and measured by a water-clock (klepsydra).

The water-clock was a simple device consisting of a large ceramic vessel with a hole that drained into a second vessel set below it. The flow of water was stopped for the reading of evidence such as laws and witness testimony. A fragment of one water-clock survives. Whether it was used for a lawcourt is not known for certain.

Laws

Litigants were responsible for researching and quoting any laws that they thought were relevant to their case. Laws were inscribed on stone blocks (stelai) and erected in various parts of the city, often, it appears, near the office of the magistrates charged with administering the particular law.

Near the end of the fifth century, a public archive was established that held copies of the laws, though the extent to which the archive was sufficiently organized to serve as a “user-friendly” source of law for potential disputants is unclear. Presumably speechwriters (logographoi see Glossary) assisted in researching and collecting laws relevant to the case.

Echinos

Most private cases in the fourth century were preceded by a mandatory, but non-binding, public arbitration procedure: if either party rejected the arbitrator’s decision, the case proceeded to trial. The Constitution of the Athenians tells us that all documents presented by the litigants at the arbitration (written witness testimony, contracts, wills, and laws), were sealed in a jar, called an echinos (“hedgehog”). The name is evidently derived from the resemblance of the jar’s shape to the animal. At trial, the parties were barred from introducing any evidence not contained in the echinos. A fragment of an echinos has been found in the Athenian agora.

This particular jar may have been used to seal the documents introduced at the anakrisis see Glossary), another pretrial procedure. Whether parties were barred from introducing new evidence after the anakrisis is disputed by scholars.

Jury Voting

Verdicts were determined by a simple majority vote. In the fifth century, jurors filed past two urns, one of which held votes for a conviction, the other those for acquittal. Each juror dropped a ballot (psephos) into one of the urns. The literal meaning of psephos is “pebble,” and jurballots in this period may in fact have been common pebbles. Objects from the fifth century voting procedure do not survive, but Aristophanes describes the process in his comedy The Wasps.

In Aristotle’s time, a slightly different voting procedure was used. Each juror was issued a set of two bronze discs with an axle running through the centers: the ballot for the defendant had a solid axle, for the plaintiff a hollow axle. Many ballots have been found in the Athenian agora.

The jurors marched past two urns, and dropped the ballots to be counted into one basket, the ballots to be discarded into another. By holding thumb and forefinger over the axle ends, the jurors were able to conceal their vote from onlookers.

Law Court Locations

Most of the Athenian courts were in the agora, the civic center and market of Athens. There was no standard plan for a law court, and in fact cases could be heard in buildings whose original or primary function was not judicial.

For example, the Odeion, a structure built for musical entertainments (ode= “song”), served as a court.

Because Athenian courts tended not to be monumental buildings, the archaeological evidence is very limited and the identifications of law court sites often tentative.

A number of locations in the agora have been identified as possible law court sites. The stone benches preserved on the west side of the agora in front of the temple of Hephaestus may have functioned as court. These benches would have served as seats for jurors.

We know that spectators sometimes observed trials. This court’s location in one of the busiest areas of the agora makes it likely that this court often drew a crowd.

Foundations of a number of buildings that may have served as law courts have been found underneath the Hellenistic Stoa of Attalos. See a brief description of these buildings and links to photos at the Athenian Agora Excavations web site.

Some scholars have identified a building on the south side of the agora dating from the sixth century B.C. as an early law court based on its prominent location, large size, and open ground plan with space for a large meeting of people.

See a brief description of the “Heliaia” and links to further photos at the Athenian Agora Excavations web site.

Unlike most Athenian courts, the homicide courts were not located in the agora. Homicide trials were tried in the open air so that those in the court would not be polluted by being under the same roof as a killer. Some types of homicide were tried on the Areopagus, literally the “Hill of Ares,” not far from the acropolis.

Pausanias tells us that the prosecutor delivered his speech from a natural stone ledge called the “rock of unforgivingness (anaideias),” while the defendant spoke from the “rock of hubris.” The location of the other four homicide courts is less certain. Although we cannot identify a precise location, the court at Phreatto was apparently somewhere on the coast.

This court was charged with judging a somewhat unlikely scenario: if a defendant in exile for a prior offense was charged with intentional homicide, he was not permitted to set foot on Athenian soil, but was obliged to deliver his defense to the court while standing on a boat anchored off shore.