Gathered here are selections from CHS publications pertaining to the songmaking of Sappho. The majority of them have been generated in Classical Inquiries, an online, rapid-publication project devoted to sharing some of the latest thinking on the ancient world with researchers and the general public, authored primarily by Gregory Nagy, Director of the Center for Hellenic Studies. Nagy’s approach, which combines diachronic and synchronic perspectives, encourages us to view Sappho’s songmaking as an evolving medium. In addition, published and forthcoming essays and two full-length books have been made available. This collection aims to contextualize new approaches to the poetic tradition of Sappho, while providing translations of primary material and overviews of different methodologies.

Diachronic Sappho: some prolegomena Diachronic Sappho: some prolegomena

From Classical Inquiries 2015.10.08: Gregory Nagy offers his own working translations of some songs attributed to Sappho, complementing his interpretations as posted in Classical Inquiries 2015.10.01. Some of these songs are part of a set of new discoveries of papyrus fragments. Nagy integrates current interpretations of the “newest Sappho” songs with earlier interpretations of songs that he began studying in the early 1970s, with special attention to his work on Songs 1, 16, 31, and 44 of Sappho. |

Once again this time in Song 1 of Sappho Once again this time in Song 1 of Sappho

From Classical Inquiries 2015.11.05: Nagy argues that the expression dēute (δηὖτε) as used at lines 15 and 16 and 18 in Song 1 of Sappho refers not only to some episodically recurrent emotion of love as experienced by the speaker but also to the seasonally recurrent performance of the song on festive occasions that he reconstructs back to the earliest attested phases of the song’s evolution. |

The Tithonos Song of Sappho The Tithonos Song of Sappho

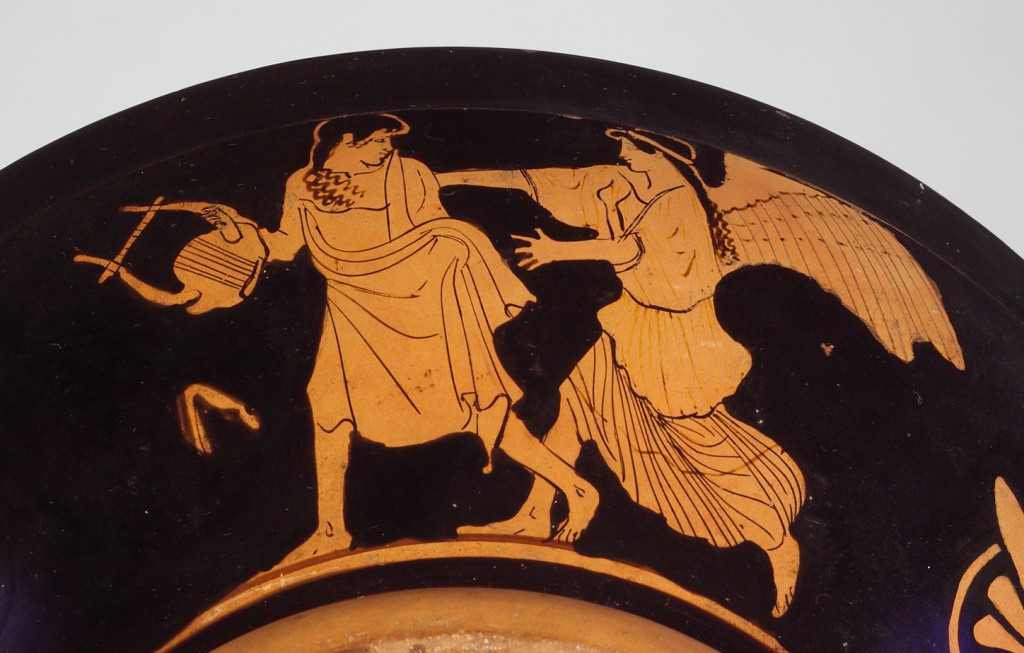

From Classical Inquiries 2015.11.12: Nagy takes up from where he left off on 2015.11.5 (above), where he explored the idea of a cycle from girl to woman back to girl in the poetics of Sappho. In that essay, Nagy noted the use of the word pais in the sense of ‘girl’ in a vase painting that showed the pursuit of a girl by a woman who was in turn pursued by the girl in a seemingly eternal cycle. Nagy sees a comparable use of the word pais in the so-called Tithonos Song of Sappho, as edited by Dirk Obbink 2010. |

Song 44 of Sappho and the Role of Women in the Making of Epic Song 44 of Sappho and the Role of Women in the Making of Epic

From Classical Inquires 2015.02.27: In H24H, Hour 4§15–20, Nagy analyzes Song 44 of Sappho, which narrates a scene that has no parallel in the Homeric Iliad. This scene centers on the wedding of Hector and Andromache. At H24H 4§20, he formulates this “take-away” from that analysis: “Song 44 of Sappho is an example of epic as refracted in women’s songmaking traditions.” |

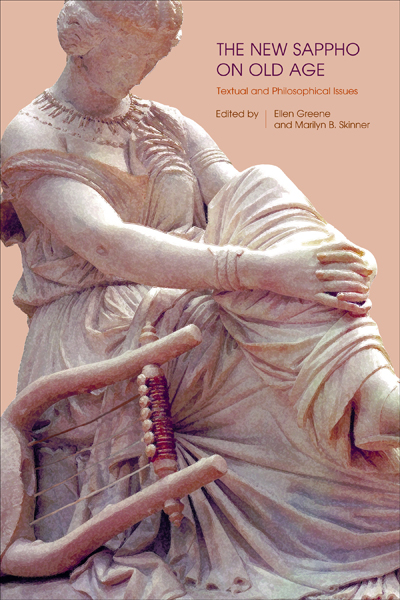

The New Sappho on Old Age: Textual and Philosophical Issues The New Sappho on Old Age: Textual and Philosophical Issues

Hellenic Studies 38: The world has long wished for more of Sappho’s poetry, which exists mostly in tantalizing fragments. So the apparent recovery in 2004 of a virtually intact poem by Sappho, only the fourth to have survived almost complete, has generated unprecedented excitement and discussion among scholarly and lay audiences alike. This volume is the first collection of essays in English devoted to discussion of the newly recovered Sappho poem and two other incomplete texts on the same papyri. Containing eleven new essays by leading scholars, it addresses a wide range of textual and philological issues connected with the find. Using different approaches, the contributions demonstrate how the “New Sappho” can be appreciated as a complete, gracefully spare poetic statement regarding the painful inevitability of death and aging. |

Genre, Occasion, and Choral Mimesis Revisited—with special reference to the “newest Sappho” Genre, Occasion, and Choral Mimesis Revisited—with special reference to the “newest Sappho”

From Classical Inquiries 2015.10.01: This essay is the third part of a tripartite project. The first part, “Genre and Occasion,” was published in ΜΗΤΙΣ (1994), and the second part, “Transmission of Archaic Greek Sympotic Songs: From Lesbos to Alexandria,” was published ten years later in Critical Inquiry (2004). The present essay is from a keynote lecture delivered by Gregory Nagy at the University of California at Berkeley on the occasion of a conference entitled “The Genres of Archaic and Classical Greek Poetry: Theories and Models.” |

The “Newest Sappho”: a set of working translations, with minimal comments The “Newest Sappho”: a set of working translations, with minimal comments

From Classical Inquiries 2015.10.08: These working translations are drawn from Classical Inquiries 2015.10.01 (above). The “newest Sappho” in the title refers to the new fragments of Sappho as published in a 2015 book edited by Anton Bierl and André Lardinois, The Newest Sappho (P. Obbink and P. GC Inv. 105, frs. 1–5). This book contains not only the new fragments of Sappho as edited by Dirk Obbink but also a set of chapters that comment extensively on those fragments. Among those commentaries is Chapter 21, “A poetics of sisterly affect in the Brothers Song and in other songs of Sappho,” an expanded version of which is already available online, with the permission of the the editors and their publisher (see below). |

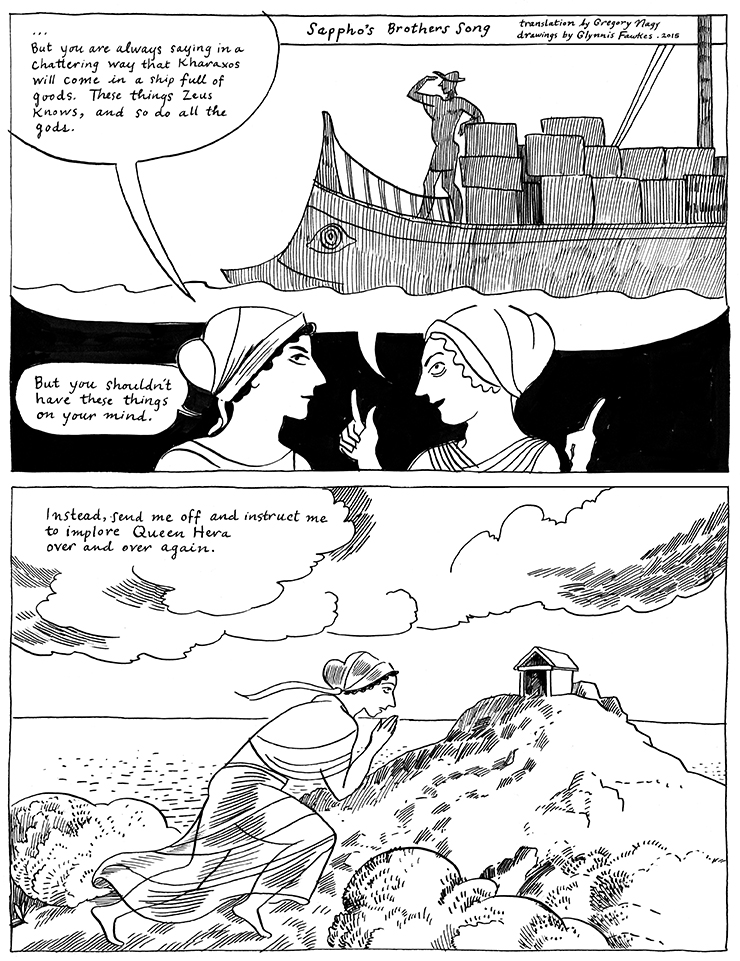

An experiment in combining visual art with translations of Sappho An experiment in combining visual art with translations of Sappho

and An experiment in combining visual art with translations of Sappho, part 2 From Classical Inquiries 2015.10.09 and 2015.11.09: Glynnis Fawkes has generously agreed to supplement with her visual art Gregory Nagy’s working translations from the “newest Sappho” as posted 2015.10.08 (above). Part 1 offers a preview of her earlier work relating to the songs of Sappho. The second installment presents one of the “newest Sappho” fragments known as the “Brothers Song.” |

A poetics of sisterly affect in the Brothers Song and in other songs of Sappho A poetics of sisterly affect in the Brothers Song and in other songs of Sappho

From Nagy, Short Writings, Volume III: “What would be so delightful about songs expressing an aristocratic woman’s tormented feelings about a brother who squandered his family’s wealth on a courtesan in Egypt?” In an attempt to answer this question, Gregory Nagy comments on the “mixed feelings” of this sister. This essay, from Short Writings: Volume III is an expanded online version of a chapter in the forthcoming book The Newest Sappho (P. Obbink and P. GC Inv. 105, frs. 1–5), edited by Anton Bierl and André Lardinois. Here Nagy argues that “the poetics of sisterly affect are so deeply rooted in the songs of Sappho that even her identity as a choral personality is shaped by such poetics.” He provides linguistic evidence that demonstrates how the name Sappho is a case of an onomatopoetic form meaning ‘sister.’ Further Reading |

Sappho’s ‘fire under the skin’ and the erotic syntax of an epigram by Posidippus Sappho’s ‘fire under the skin’ and the erotic syntax of an epigram by Posidippus

From Classical Inquiries 2015.07.08: The poet Posidippus of Pella, who lived in the third century BCE, composed an epigram that memorializes the life and times of the courtesan from Naucratis who was passionately loved by Kharaxos, brother of Sappho. In this epigram, however, the name of the courtesan is not Rhodōpis ‘she with the rosy looks’, as she is called by Herodotus, but Dōrikha. Here Nagy argues that Rhodōpis is in fact an alternative name for the same woman who is called Dōrikha in the epigram of Posidippus. The question remains, how do ‘rosy looks’ connect with the erotic syntax of body language in the epigram by Posidippus? The answer, Nagy argues, has to do with the fact that the eroticism of the khrōs– / khrōt– ‘complexion’ is a distinctive feature of Sappho’s own poetics. |

Echoes of Sappho in two epigrams of Posidippus Echoes of Sappho in two epigrams of Posidippus

From Classical Inquiries 2015.11.19: Nagy has argued that Posidippus’ Epigrams 52 and 55 reveal echoes from Sappho’s Song of Tithonos (Nagy 2010). Epigram 55 actually refers to Sappho by name. Viewing the words of Epigram 55 together with the words of Epigram 52, Nagy argues that the poetry of Posidippus is echoing the references to a choral interaction between paides ‘girls’ and the persona of Sappho in the Tithonos Song. And such a reference to choral performance, as we will see, does not rule out the possibility that the same kind of reference could also be made in sympotic and concertizing performances of Sappho’s songs. |

Girl, interrupted: more about echoes of Sappho in Epigram 55 of Posidippus Girl, interrupted: more about echoes of Sappho in Epigram 55 of Posidippus

From Classical Inquiries 2015.12.03: Epigram 55 of Posidippus, a poet who flourished in the third century BCE, refers to the songs of Sappho, but the reference to Sappho in that epigram is complex. Nostalgically, the words of the epigram recall the happy times when this girl together with her girlfriends were singing the love songs of Sappho, sung one after another. Such singing of Sappho’s songs, Nagy argued (2015.11.19, above), promises to cancel the interruption of the girl’s happy life. But what is the context for such singing? Following Classical Inquiries 2015.11.19, Nagy reconsiders this question in e-conversations with a few dear friends. |

Herodotus and a courtesan from Naucratis Herodotus and a courtesan from Naucratis

From Classical Inquiries 2015.07.01: Nagy explicates the History of Herodotus, at 2.134–135, where we read about a beautiful hetaira or ‘courtesan’ named Rhodōpis. This woman, according to the reportage of ‘some Greeks’ as opposed to others (metexeteroi … Hellēnōn), commissioned the building of the third and smallest of the three pyramids at the site now known as Giza. Having highlighted the widespread fame of Rhodōpis in the song culture of the ancient Greek world, Herodotus returns, in ring composition, to the relationship between this sexually irresistible woman and the man who paid for her freedom, Kharaxos of Mytilene, brother of Sappho. This man, as the lover of Rhodōpis, figures in the songs of Sappho, who sings of his relationship disapprovingly. Herodotus’ report links what he says about the fame of Rhodōpis throughout the Greek-speaking world with the songs once sung by Sappho herself about the love-affair of her errant brother with this sexually irresistible courtesan. |

Sappho in the Making: The Early Reception Sappho in the Making: The Early Reception

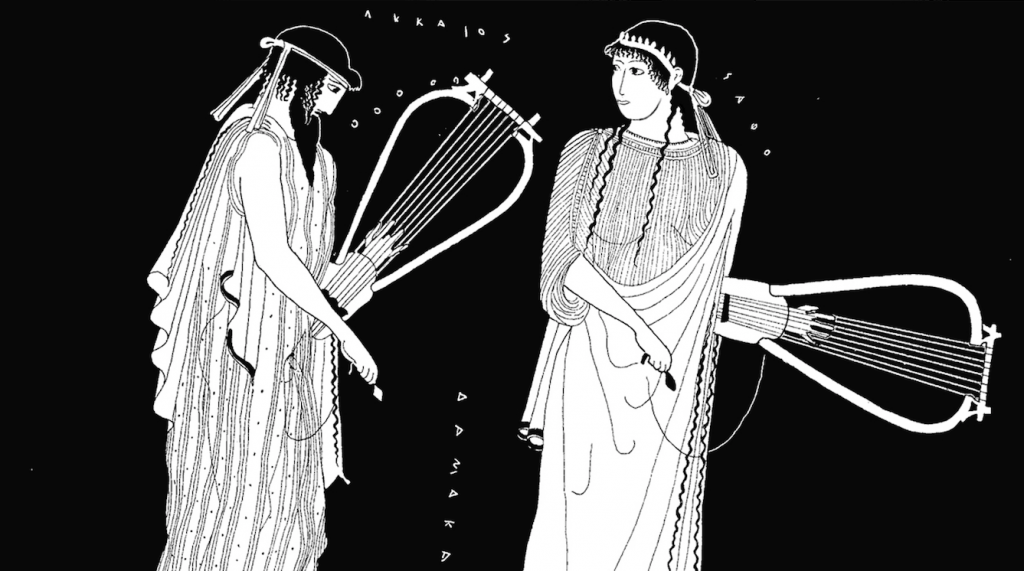

Hellenic Studies 28: This book offers the first interdisciplinary and in-depth study of the cultural practices and ideological paradigms that conditioned the politics of the “reading” of Sappho’s songs in the early and most pivotal stages of her reception. In this wide-ranging synthesis, Dimitrios Yatromanolakis investigates visual representations and ancient texts in their synchronic and diachronic multilayeredness to trace the discursive nexuses that defined the making of “Sappho” in the late archaic, classical, and early Hellenistic periods. Offering a systematic analysis of the contextual cues provided by vase paintings and focusing on the sociocultural institution of the symposion, this book explores the intricate modes of the assimilation of Sappho’s poetry into diverse social, aesthetic, and performative contexts. Drawing on a number of disciplines, including archaeology, papyrology, and anthropology, Sappho in the Making articulates a new methodological Problematik on the reception of archaic Greek socioaesthetic cultures. |

Victum of the Muses, Chapter 8. Sappho: The Barbed Rose Victum of the Muses, Chapter 8. Sappho: The Barbed Rose

Hellenic Studies 11: One would not expect Sappho, who was associated largely with delicate love poetry, to resemble the patterns followed by Aesop and Archilochus. Yet, though she does not have as full a dossier of the scapegoat hero cult themes as do Aesop and Archilochus, and her life is not as (folklorically) well documented as theirs, even so, certain themes link her to the familiar pattern. Though the greater part of her poetry dealt with exquisitely evoked love, yet there was a definite current of blame running through her poetic corpus. And Archilochus shows that the satiric muse is not necessarily divorced from poetic sophistication. The poet can take the archaic categories of praise and blame and exploit them with high artistic skill. Love can obviously inspire praise poetry, but since it often produces such emotions as loss, betrayal, and bitterness, it can also inspire blame. |

Did Sappho and Alcaeus Ever Meet? Did Sappho and Alcaeus Ever Meet?

From Nagy, Short Writings, Volume II: “Myth and ritual tend to be segregated from one another in classical studies. A contributing cause is a general lack of sufficient internal evidence concerning the relationship of myth and ritual in ancient Greek society. Another contributing cause is a failure to consider the available comparative evidence. This situation has led to an overly narrow understanding of myth and ritual as concepts—and to the emergence of a false dichotomy between these two narrowed concepts. A sustained anthropological approach can help break down this dichotomy.” Applying such an approach, [Nagy has] argued that myth is actually an aspect of ritual in situations where a given myth comes to life in performance—and where that performance counts as part of a ritual. He develops this argument further here by considering mythological themes evoked in singing the songs of Sappho and Alcaeus in various ritual contexts, focusing on themes involving Aphrodite and Dionysus, which will be relevant to the question asked in the title: did Sappho and Alcaeus ever meet?” |

Lyric and Greek Myth Lyric and Greek Myth

From Nagy, Short Writings, Volume I: “The poets of lyric in the archaic period became the models for performing lyric in the classical period. … It is clear that a given lyric composition could be sung or recited, instrumentally accompanied or not accompanied, and danced or not danced. It could be performed solo or in ensemble. Evidently, all these variables contributed to a wide variety of genres, but the actual categories of these genres are in general difficult to determine. Moreover, the categories as formulated in the postclassical period and thereafter may be in some respects artificial. Such difficulties can be traced back to the fact that the actual writing down of archaic lyric poetry blurs whatever we may know about the occasion or occasions of performance. The genres of lyric poetry stem ultimately from such occasions. … In any case, the basic fact remains that the composition of poetry in the archaic period came to life in performance, not in the reading of something that was written. Accordingly, the occasions of performance need to be studied in their historical contexts. In this presentation, the primary test case for studying occasions of performance is the lyric poetry attributed to Sappho and Alcaeus. The historical context of this poetry is relatively better known than the contexts of other comparable poetry. The place in question is the island of Lesbos, off the northern coast of Asia Minor. The time in question is around 600 BCE.” |