To mark Greek Independence Day on March 25, 2025, Nevila Pahumi, Modern Greek specialist at the Library of Congress, offers a historical background in this blogpost and presents items in the LC collection pertaining to the era of the Greek Revolution from 1821 and the birth of the modern Greek nation, whereas Rebecka Lindau, chief librarian at Harvard’s Center for Hellenic Studies, goes back some 2,500 years to the birth of Athenian democracy and features some rare books on the subject from a physical exhibition at the Center in connection with a celebratory evening organized by the Greek Embassy in cooperation with the CHS.

Athenian Democracy 6th-4th Century BCE reflected in the CHS Rare Book Collection

By Rebecka Lindau

Since the Greek Revolution and Greek Independence was declared on March 25, 1821, Greece has been a mostly democratic country with periods of monarchy and oligarchy, most recently and infamously 1967-1974. The Greek Revolution took inspiration from both the French and American revolutions, which had at their core a desire for representation, power by the people, δημοκρᾰτία (δῆμος, people, and κρᾰ́τος, strength, power) as opposed to power by one, monarchy, or self, autocracy, or power of the few, oligarchy. In addition to those more recent models, there were democratic revolutions and dictatorships in Greece’s own past, in ancient Greece, most notably in ancient Athens in the 6th-4th centuries BCE. In the late 6th century BCE, an Athenian statesman by the name of Cleisthenes introduced reforms in Athens leading to a democratic system characterized by the principles of one person, one vote, freedom of speech, and freedom of assembly. There were other Greek democratic city-states in antiquity but none as well-documented as Athens.

Athenian democracy did not include all residents of Athens. You had to be a citizen, not a foreigner, not a slave, over 18 years of age, and you had to be male. If you fulfilled these criteria, you were afforded direct democracy, i.e., you could gather in the Assembly (Ἐκκλησία) to vote on various proposals. The Athenian Assembly met several times a year, and in the outdoors on the Pnyx hill to accommodate the many thousands of voters. Voting on legislative, military, financial, etc., matters was usually done by the counting of hands; the majority vote prevailed. Participants from outlying areas could have their travels to central Athens subsidized to ensure voter participation. Expenses could be reimbursed but potential attempts at profiting were illegal.

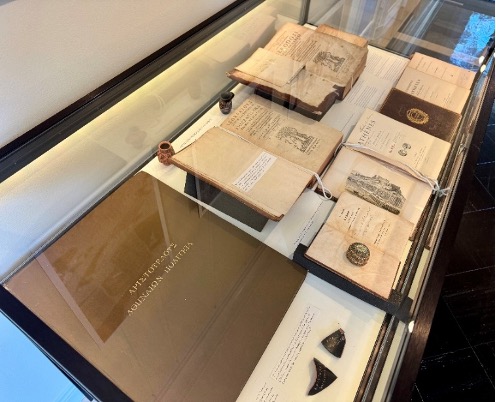

Voting on exiling citizens deemed dangerous or autocratic was not done in the open, but by anonymously writing names on pottery sherds, so called ostraca, examples of which are included in an exhibition at the CHS in connection with Greek Independence Day.

Cleisthenes’ reforms also stipulated that some matters before the Assembly were to be decided by a Council (Βουλή) of 500 individuals, chosen by lottery from ten tribes constituting the city-state, which in part was an effort to weaken the landowning aristocracy as was also the use of demotics, the deme, the geographic division to which a citizen belonged, instead of patronymics, the father’s and forefathers’ names in the voter rolls. In addition to the political bodies, there were law courts in which laws and other decisions made in the Assembly could be challenged, including that of ostracism. The various political and judiciary bodies were to ensure checks and balances and equal representation.

The Athenian democratic system under Cleisthenes had in 514 BCE been preceded by a revolutionary act by two Athenians, Harmodius and Aristogeiton, referred to as Tyrannicides (Τῠραννοφόνοi) or Liberators (Ἐλευθέριοι). They had killed Hipparchus, brother of the tyrant and autocrat Hippias whom the Spartans eventually exiled, ending the brothers’ dictatorship (Thuc. 6. 56–59; Arist. Ath. Pol. 18). The action of the two loving companions seemed not to have been primarily to oppose Hipparchus’ rule, though, but more to avenge a personal affront. Regardless, it launched a revolution and ushered in a democratic system of one citizen, one vote.

“I will bear my sword in a myrtle branch, like Harmodius and Aristogeiton when the two of them killed the tyrant and made Athens a place of political equality. Beloved Harmodius, you are not dead at all; instead, they say you are in the Isles of the Blessed, where swift-footed Achilles is, and Tydeus’ son they say the noble Diomedes. I will bear my sword in a myrtle branch, like Harmodius and Aristogeiton when at a sacrifice in honor of Athena the two of them killed the tyrant Hipparchus. The story of you two will always survive in our land, beloved Harmodius and Aristogeiton, how the two of you killed the tyrant and made Athens a place of political equality” (Ath. Deipnosophistae 15.695a-b).

Prior to the dictatorial brothers Hippias and Hipparchus there was an Athenian chief magistrate or ruler (archon), lawgiver, and poet by the name of Solon (d. 560 BCE) who had been considered fair and wise. He had warned against riches too great being poured upon men of unbalanced soul, and he had introduced a series of reforms such as regulating elections to various offices by lot according to an already established system of property classes (based on birth and wealth, the quantity of cereal production), appointing a Council of 400, extending the mandate of the law court of the Areopagus to settle disputes (Athens’ first written law code was attributed to an Athenian by the name of Draco, as in “Draconian laws,” thus named because most offenses seem to have been punished by death), and, above all, Solon had ended the serfdom of the previous era by canceling all debt. These reforms facilitated the introduction of Cleisthenes’ democratic system.

One of our most important sources for Athenian democracy is Aristotle’s (or a student’s) The Constitution of Athens.

The following are excerpts from this text outlining ancient Athens’ democratic history (the English translations from ancient Greek texts in this blogpost are taken either verbatim or have been slightly modified from Loeb Classical Library editions. The italics for emphasis are my own).

“The form of the ancient constitution that existed before Draco was as follows. Appointment to the supreme offices of state went by birth and wealth; and they were held at first for life, and afterwards for a term of ten years” (Arist. Ath. Pol. 3).

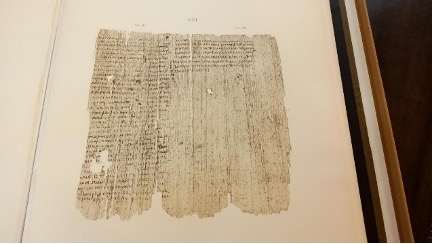

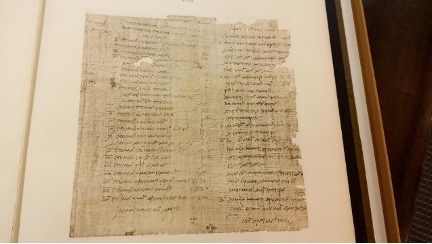

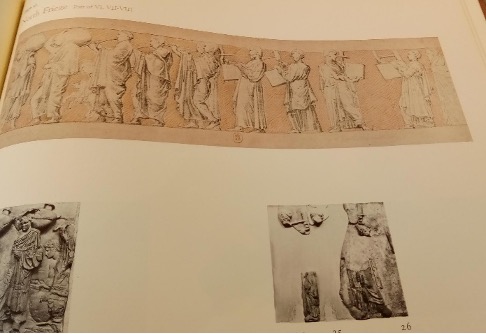

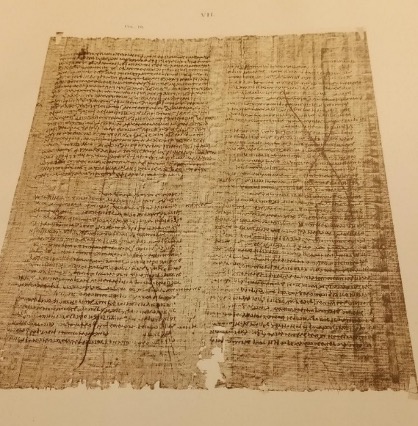

“…when… he [Cleisthenes] had become Chief of the multitude, in the fourth [508 BCE] year after the deposition of the tyrants…he first divided the whole body into ten tribes instead of the existing four, wishing to mix them up, in order that more might take part in the government; from which arose the saying, ‘Don’t draw distinctions between tribes,’ addressed to those who want to inquire into people’s clans. Next, he made the Council consist of five hundred members instead of four hundred, fifty from each Tribe, whereas under the old system there had been a hundred… He also portioned out the land among the demes into thirty parts, ten belonging to the suburbs, ten to the coast, and ten to the inland district; and he gave these parts the name of Thirds, and assigned them among the Tribes by lot, three to each, in order that each Tribe might have a share in all the districts. And he made all the inhabitants in each of the demes fellow-demes men of one another, in order that they might not call attention to the newly enfranchised citizens by addressing people by their fathers’ names, but designate people officially by their demes; owing to which Athenians in private life also use the names of their demes as surnames…” (Arist. Ath. Pol. 21, image below, from the CHS Rare Book and Manuscript Collection).

“These reforms made the constitution much more democratic than that of Solon; for it had come about that the tyranny had obliterated the laws of Solon by disuse, and Cleisthenes aiming at the multitude had instituted other new ones, including the enactment of the law about ostracism…which had been enacted owing to the suspicion felt against the men in positions of power because Peisistratus when leader of the people and general set himself up as tyrant” (Arist. Ath. Pol. 22, image below, from the CHS Rare Book and Manuscript Collection).

In his work Politics, Aristotle gives a definition of democracy.

“The founding principle of a democratic state is liberty (Ὑπόθεσις μὲν οὖν τῆς δημοκρατικῆς πολιτείας ἐλευθερία); which, as is generally asserted, can only be enjoyed in such a state; this they affirm to be the great end of every democracy. One principle of liberty is for all to rule and be ruled in turn, and indeed democratic justice is the application of numerical not proportionate equality; whence it follows that the majority must be supreme, and that whatever the majority approve must be the end and the just. Every citizen, it is said, must have equality, and therefore in a democracy the poor have more power than the rich, because there are more of them, and the will of the majority is supreme. This, then, is one note of liberty which all democrats affirm to be the principle of their state. Another is that everyone should live as they please (ἓν δὲ τὸ ζῆν ὡς βούλεταί τις). This, they say, is the objective of democracy because, on the other hand, not to live as one pleases is the mark of a slave. This is the second characteristic of democracy, whence has arisen the claim of men to be ruled by none, if possible, or, if this is impossible, to rule and be ruled in turns; and so it contributes to the freedom based upon equality” (Aris. Pol. 6.1.6-7, 1317b).

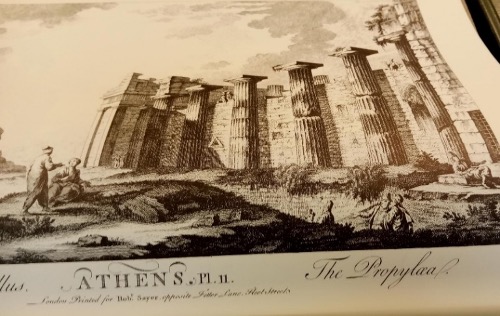

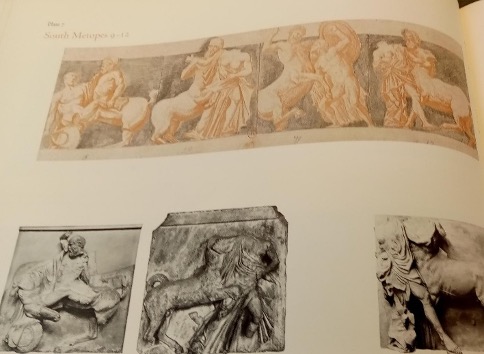

Under the democratic politician and general Pericles (461-429 BCE) the city-state undertook public works projects to beautify the city while at the same time employing thousands of citizens. The greatest architectural achievement was the innovations and expansion of the building complex of the Acropolis, the formal entrance way Propylaea, the Erechtheion (the temple of Athena Polias; Erechtheus was the name of a legendary king to whom the founding of the polis of Athens was attributed and later identified with Poseidon), the temple of Athena Nike, and the Temple of Virgin Goddess Athena, the Parthenon, with its metopes celebrating epic battles in Athens’ past, real and imaginary, and its frieze representing the Panathenaia, the most important of Athens’ many religious festivals, and the Panathenaic procession in honor of the Goddess and the genealogy and glory of the Athenian polis.

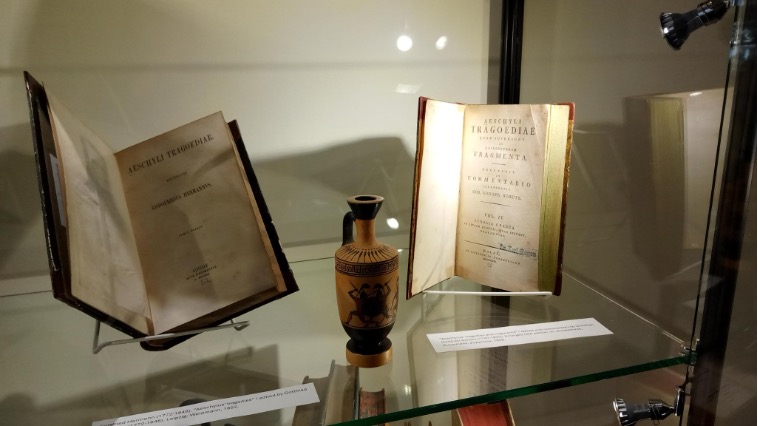

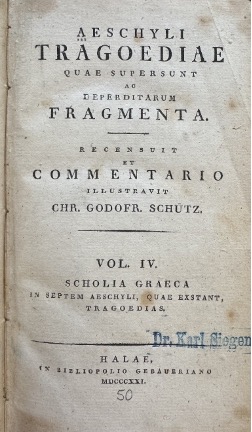

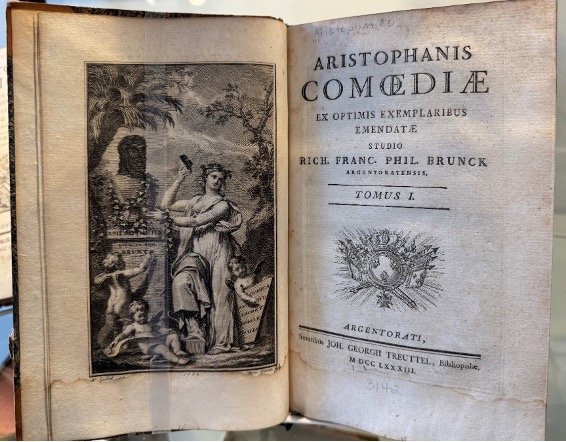

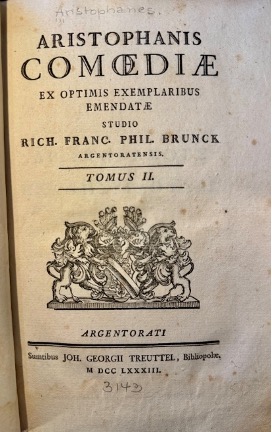

The democratic period under Pericles, lauded especially by historian Thucydides, and who by establishing the Delian League of allies created what many scholars refer to as an Athenian Empire, also often called “the golden age,” saw not only art and architecture flourish, but also theater. The great tragedies by Aeschylus (e.g., Suppliant Women with women who are granted sanctuary by the demos in Athens after fleeing forced marriages in Egypt, and Eumenides with Orestes on trial on the Areopagus for matricide with the Furies (pre-trial Eumenides) as prosecutors and Athena as judge), Sophocles (Antigone who defies sacred laws and taboos and stands up to a dictator), and Euripides (Iphigenia at Aulis in which Clytemnestra stands up to the unreasonable and cruel dictates of a tyrant, her husband), and comedy writer Aristophanes (Assemblywomen in which a group of women dress as men in order to get women into the Athenian Assembly) often explored the themes of democracy and tyranny, and also the subject of female agency. In plays by these Athenian playwrights such as the ones mentioned and in others; for example, Medea, Hecuba, and Lysistrata, women express feminist views that even today seem radical.

The status of women in ancient Greece was not monolithic. Women in Sparta and parts of Asia Minor seemingly had equal rights to men. While it is true that Athenian women did not have the right to vote, they had leading roles in religious affairs which encompassed virtually every aspect of life in ancient Greece; for example, the Goddess Athena and her high priestess in the Parthenon and the female officiants of the Panathenaia. Athenian Socrates had female disciples. Socrates in turn was a follower of the teachings of Diotima, a female philosopher from Mantinea. Aspasia was by all accounts an impressive woman who led an intellectual salon in Athens, frequented by Socrates and Plato. Her marriage to Pericles seems to have lasted some twenty years until Pericles’ death. Comedy lampooned her just like it did many famous men, especially politicians, including Pericles, as today, and women, referring to her as a prostitute and a madam.

In the (second) Peloponnesian War, Megara was an ally of Sparta. Aspasia was from Miletus, a somewhat uneasy ally of Athens’ and historically close to Megara.

“…some tipsy, cottabus-playing youths [a game popular at symposia] went to Megara and kidnapped the whore Simaetha. And then the Megarians…in retaliation stole a couple of Aspasia’s whores, and from that the onset of war broke forth upon all the Greeks: from three sluts! And then in wrath Pericles, that Olympian, did lighten and thunder and stir up Greece, and started making laws worded like drinking songs, that Megarians should abide neither on land nor in market nor on sea nor on shore” (Ar. Ach. 527).

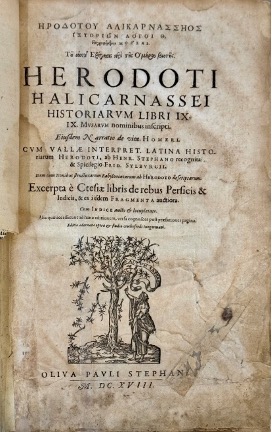

An important source for the history of Athenian democracy is Greek historian, geographer, and ethnographer Herodotus (ca. 484-ca. 425 BCE). Here he describes Cleisthenes, his reforms, and the beginning of Athenian democracy.

“Athens, which had before been great, grew now yet greater when rid of her despots; and those that were of chief power there were two, Cleisthenes an Alcmaeonid…and Isagoras son of Tisandrus, a man of a notable house, but of what lineage I cannot tell; his kinsfolk sacrifice to Zeus of Caria. These men with their factions fell to contending for power, wherein Cleisthenes being worsted took the commonalty into partnership. Presently he divided the Athenians into ten tribes, instead of four as formerly; he called none any more after the names of the sons of Ion, Geleon, Aegicores, Argades, and Hoples, but invented for them names taken from other heroes, all native to the country save only Aias; him he added, albeit a stranger, because he was a neighbor and an ally” (Hdt. 5.66).

Herodotus recounts a debate among Persian military leaders during the Greco-Persian Wars (499-449 BCE) about the advantages and disadvantages of the different systems of governance. The wars were preceded by the Persians having conquered Greek-inhabited parts of Ionia, Asia Minor, and installed dictators, tyrants to rule them. The latter word comes from τῠ́ραννος which in ancient Greek simply means “king” but came to have negative connotations as a result of a series of ruthless despots in Greek antiquity. The Persian army under one of the tyrants, Aristagoras of Miletus, led a failed invasion of the Greek island of Naxos. Aristagoras was dismissed, then led an Ionian Revolt, which eventually pulled in also Athens, against his former backers, the Persians.

“Otanes was for giving the government to the whole body of the Persian people. “I hold,” he said, “that we must make an end of monarchy; there is no pleasure or advantage in it…. The advantage which he holds breeds insolence, and nature makes all men jealous. This double cause is the root of all evil in him; sated with power he will do many reckless deeds, some from insolence, some from jealousy. For whereas an absolute ruler, as having all that heart can desire, should rightly be jealous of no man, yet it is contrariwise with him in his dealing with his countrymen; he is jealous of the safety of the good, and glad of the safety of the evil; and no man is so ready to believe calumny. Of all men he is the most inconsistent; accord him but just honor, and he is displeased that you make him not your first care; make him such, and he damns you for a flatterer. But I have yet worse to say of him than that; he turns the laws of the land upside down, he rapes women, he puts high and low to death… All offices are assigned by lot, and the holders are accountable for what they do therein; and the general assembly arbitrates on all counsels” (Hdt. 3.80).

“Such was the judgment of Otanes: but Megabyzus’ counsel was to make a ruling oligarchy. “I agree,” said he, “to all that Otanes says against the rule of one; but when he bids you give the power to the multitude, his judgment falls short of the best. Nothing is more foolish and violent than a useless mob; to save ourselves from the insolence of a despot by changing it for the insolence of the unbridled commonalty—that were unbearable indeed…Let those stand for democracy who wish ill to Persia; but let us choose a company of the best men and invest these with the power” (Hdt. 3.81).

“Darius was the third to declare his opinion in favor of monarchy. “Methinks,” said he… “I hold that monarchy is by far the most excellent. Nothing can be found better than the rule of the one best man; his judgment being like to himself, he will govern the multitude with perfect wisdom, and best conceal plans made for the defeat of enemies” (Hdt. 3.82).

Herodotus himself seems to favor democracy.

“Thus grew the power of Athens; and it is proved not by one but by many instances that equality [ἰσηγορία, Brill’s Dictionary of Ancient Greek translates the word as both “parity of rights” and as “equal freedom of speech”] is a good thing; seeing that while they were under tyrants the Athenians were no better in war than any of their neighbors, yet once they got rid of the tyrants they were far the best. This, then, shows that while they were oppressed, they let themselves be beaten because they were working for a master, but when they were freed, each one was eager to achieve something for himself” (Hdt. 5.78).

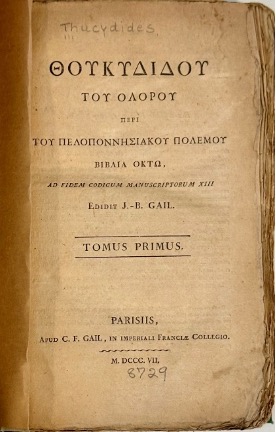

The Greek historian and military leader Thucydides (460-401 BCE), our chief source for the Peloponnesian Wars (431-404 BCE) between Athenians and their allies and the Spartans and theirs, argued that a reason for the war was defense of the Athenian democratic system.

Thucydides relates a speech by Syracusan military leader Athenagoras as the Athenians are about to invade Sicily. He seemed to have supported Athens’ democratic system when he was speaking against the Athenian invasion.

Athenagoras of Syracuse, “Some will say that a democracy is neither wise nor equitable, and that those that have property are more competent to rule best. But I say, first, that democracy is a name for all, oligarchy for only a part; next, that while the wealthy are the best guardians of property, the wise would be the best counsellors, and the many, after hearing matters discussed, would be the best judges; and that these classes, whether severally or collectively, enjoy a like equality in a democracy. An oligarchy, on the other hand, gives the many a share of the dangers, but of the advantages it not merely claims the lion’s share, but even takes and keeps all” (Thuc. 6.39).

Here Thucydides recounts a story about the Athenian military leader Alcibiades who in exile had gone over to the enemy side (the Spartans and later also the Persians) and was a chief proponent of invading Sicily, the Sicilian Expedition, and a conspiracy against democracy in favor of a king.

“Alcibiades sent word to the most influential men among them to make mention of him to the best people and say that he wished to come home on condition of there being an oligarchy and not the villainous mob-rule that had banished him…” (Thuc. 8.47).

Unlike Herodotus who appears to have favored democracy, Thucydides in his admiration for Pericles seems to have preferred an oligarchic or aristocratic, as in rule of the best, system although the Athenian democratic institutions prospered under Pericles with one major restriction (which several years later Pericles reversed).

“…owing to the large number of citizens an enactment was passed on the proposal of Pericles confining citizenship to persons of citizen birth on both sides” (Arist. Ath. Pol. 26).

“And so Athens, though in name a democracy, gradually became in fact a government ruled by its foremost citizen. But the successors of Pericles, being more on an equality with one another and yet striving each to be first, were ready to surrender to the people even the conduct of public affairs to suit their whims. And from this, since it happened in a great and imperial state, there resulted many blunders, especially the Sicilian expedition, which was not so much an error of judgment, when we consider the enemy they went against, as of management…” (Thuc. 2.22).

Here Thucydides relates a funerary speech Pericles gave for the fallen in the Persian Wars in which Pericles lauded the Athenian democratic constitution.

“We follow a constitution which does not imitate the laws of our neighbors, but we are rather a model for others to follow. Its name is democracy because power lies in the hands of the many, not the few. Our laws afford equal justice to all in the settlement of their private disputes, but when it comes to reputation, we assign public offices on the basis of personal merit, and no citizen is preferred to another because he belongs to a higher social class, nor is lack of means a barrier from attaining renown and public honor for anyone who can be of service to the city…we keep our city open to the world, and never expel foreigners to prevent them from learning or seeing anything which, when revealed, an enemy might find useful to know. For we place our trust less in deceit and machinations than in the bravery of our men on the battlefield” (Thuc. 2.37).

Another historian, military leader, and philosopher, Xenophon (ca. 430–355/354 BCE) in his work Anabasis describes himself as a democratic orator, rhetor, who wins over the Ten Thousand, Greek mercenaries who under Cyrus the Younger marched into the Persian Empire in an attempt at conquering it. The army he describes was organized like the democratic polis with its Assembly.

“…[Spartan general in Cyrus’ army] Cheirisophus said…And now, gentlemen,” he went on, “let us not delay; withdraw and choose your commanders at once, you who need them, and after making your choices come to the middle of the camp and bring with you the men you have selected; then we will call a meeting (assembly) there of all the troops…When these elections had been completed, and as day was just about beginning to break, the commanders met in the middle of the camp; and they resolved to station outposts and then call an assembly of the soldiers” (Xen. An. 3.1-2).

Throughout Athens’ democratic history threats to its system of government and values sprang up fairly regularly. Many tyrants were demagogues (a word that in Greek simply translates as “leader of the people”) and what we today might call populists. Some came from nobility or inherited the kingship. They were seldom self-made men.

Following Solon, a series of aristocratic and dictatorial men like Peisistratus, Hippias and Hipparchus had come to power. Peisistratus and his sons Hippias and Hipparchus seemed to have been benevolent initially, even confiscating land from the wealthy to give to the poor. Peisistratus introduced the Panathenaic Games and other religious festivals. Hipparchus erected theater performances and recruited poets. Their reigns, however, became more despotic, especially after the assassination of Hipparchus where many citizens thought to have aided or supported the Tyrannicides were put to death. Eventually when the Spartans banished Hippias, he joined the court of Persian king Darius.

Aristotle recounts a story about how the tyrant Peisistratus who although “he had seized the government proceeded to carry on the public business in a manner more constitutional than tyrannical” and the propaganda machine preceding it.

“Having first spread a rumor that Athena was bringing Peisistratus back, he found a tall and beautiful woman, according to Herodotus a member of the Paeanian deme, but according to some accounts a Thracian flower-girl from Collytus named Phyē, dressed her up to look like the goddess, and brought her to the city with him, and Peisistratus drove in a chariot with the woman standing at his side, while the people in the city marveled and received them with acts of reverence” (Arist. Ath. Pol. 14).

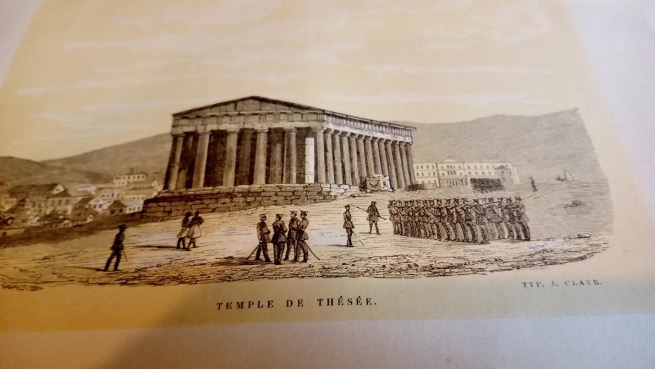

Another approach to seizing control, recounted in the Constitution of Athens, was to lure the people during an Assembly to bring their arms but leave them at the forecourt of the Acropolis during which time the arms were being locked up in a neighboring building belonging to the Temple of Theseus. The people were told not to worry about their weapons but attend to private affairs and leave the affairs of the state to the king (Arist. Ath. Pol. 15).

The text continues:

“This was the way, therefore, in which the tyranny of Peisistratus was originally set up, and this is a list of the changes that it underwent. Peisistratus’s administration of the state was, as has been said, moderate, and more constitutional than tyrannical; he was kindly and mild in everything, and in particular he was merciful to offenders, and moreover he advanced loans of money to the poor for their industries, so that they might support themselves by farming. In doing this he had two objectives, to prevent their remaining in the city and make them stay scattered about the country, and to cause them to have a moderate competence and be engaged in their private affairs, so as not to desire nor have time to attend to public business” (Arist. Ath. Pol. 16).

It turns out that even under a benevolent dictator, most Athenians preferred a democratic system. Then there were dictators who were not so benevolent. The Thirty Tyrants, installed by Sparta after the Athenian defeat in the (second) Peloponnesian War (in 404 BCE), killed thousands of Athenians, confiscated their property, and expelled many democratic politicians and ordinary citizens who were considered “unfriendly” to the new regime. The number of citizens was reduced from ca. 10,000 to 3,000.

Thucydides describes the atmosphere prior to the coup against the Thirty Tyrants of 411 led by Athenians Peisander and Antiphon (the latter was an early writer of speeches for others to use in their trial defenses).

“Fear, and the sight of the numbers of the conspirators, closed the mouths of the rest; or if any ventured to rise in opposition, he was presently put to death in some convenient way, and there was neither search for the murderers nor justice to be had against them if suspected; but the people remained motionless, being so thoroughly cowed that men thought themselves lucky to escape violence, even when they held their tongues. An exaggerated belief in the numbers of the conspirators also demoralized the people, rendered helpless by the magnitude of the city…and being without means of finding out what those numbers really were…the conspirators having in their ranks persons whom no one could ever have believed capable of joining an oligarchy; and these it was who made the many so suspicious, and so helped to procure impunity for the few, by confirming the commons in their mistrust of one another” (Thuc. 8.65-66).

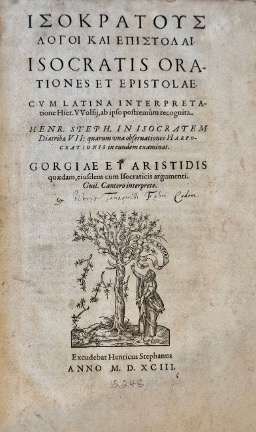

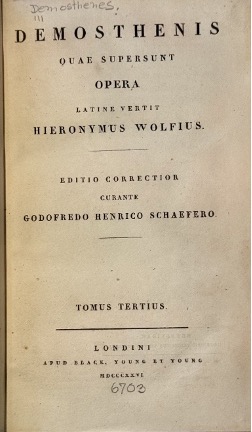

In the Athenian democratic system, there were no lawyers in the modern sense. An accused man had to defend himself, though he could hire a speechwriter to help him do so. Demosthenes (384–322 BCE) and Isocrates (436-338 BCE) were well-known Athenian speechwriters and rhetoricians.

Isocrates credits Theseus, the legendary king and hero, with introducing the foundations of democracy, already in pre-historic times.

“For he [Theseus] saw that those who seek to rule their fellow-citizens by force are themselves the slaves of others, and that those who keep the lives of their fellow-citizens in peril themselves live in extreme fear…he saw them despoiling the temples of the gods, putting to death the best of their fellow-citizens, distrusting those nearest to them, living lives no more free from care than do men who in prison await their death…Theseus despising all these and considering such men to be not rulers, but pests, of their states, demonstrated that it is easy to exercise the supreme power and at the same time to enjoy as good relations as those who live as citizens on terms of perfect equality. In the first place, the scattered settlements and villages of which the state was composed he united, and made Athens into a city-state so great that from then even to the present day it is the greatest state of Hellas: and after this, when he had established a common fatherland and had set free the minds of his fellow-citizens…And he was so far from doing anything contrary to the will of the citizens that he made the people masters of the government…he did not, as the other rulers did habitually, impose the labors upon the citizens and himself alone enjoy the pleasures; but the dangers he made his own, and the benefits he bestowed upon the people in common. In consequence, Theseus passed his life beloved of his people and not the object of their plots, not preserving his sovereignty by means of alien military force, but protected, as by a bodyguard, by the goodwill of the citizens, by virtue of his authority ruling as a king, but by his benefactions as a popular leader; for so equitably and so well did he administer the city that even to this day traces of his clemency may be seen remaining in our institutions” (Isoc. Hel. 32-37).

Both Isocrates and Demosthenes famously spoke in vain against the decline of democracy and the encroaching power of Macedon under Philip II. In the manuscript and CHS facsimile of The Constitution of Athens through papyrus reuse there are parts of scholia for Demosthenes’ In Midiam (Against Meidias) in which the orator argued that if the law is undermined by wealthy bullies, a democratic state ceases to exist, and that citizens acquire power and authority in all state-affairs due “to the strength of the laws” (In Midiam 223, image below).

In the Philippics, Demosthenes tries to encourage the listless men in the Athenian Assembly, who either did not think the situation was sufficiently dire or felt powerless to rise up against Philip, a fellow Greek if not a fellow Athenian, but also not a “barbarian,” a non-Greek speaker.

“Do not believe that his present power is fixed and unchangeable like that of a god. No, men of Athens; he is a mark for the hatred and fear and envy even of those who now seem devoted to him…At present, however, all these feelings are repressed and have no outlet, thanks to your indolence and apathy, which I urge you to throw off at once. For observe, Athenians, the height to which the fellow’s insolence has soared: he leaves you no choice of action or inaction; he blusters and talks big…he cannot rest content with what he has conquered; he is always taking in more, everywhere casting his net round us” (Dem. Philippics 1.8-9).

“Though all who aim at their own aggrandizement must be checked, not by speeches, but by practical measures, yet…we prefer to dilate on Philip’s shocking behavior and the like topic” (Dem. Philippics 2.3).

“Athenians, if anyone views with confidence the present power of Philip and the extent of his dominions, if anyone imagines that all this imports no danger to our city and that you are not the object of his preparations, I must express my astonishment…” (Dem. Philippics 2.6).

Fellow speech-writer Isocrates tried flattery rather than direct attack; that, too, in vain.

“And do not be surprised if, throughout my discourse, I endeavor to lead you to mildness, love of mankind, and good services towards the Hellenes; for I see that harshness is equally grievous to those who show it and to those who experience it, while mildness is in good repute, not only amongst humans and all other living creatures, but even amongst the gods…” (Isoc. Philippus 116-117).

When Philip, and later his son Alexander the Great, threatened Athens and its democratic system, a largely symbolic and futile act to preserve its cherished system was undertaken by the Council of 500 which erected in the Agora, Athens’ political and commercial center, a bronze statue to honor Δημοκρατία, Democracy personified.

Some 2100 years later, in the city of Odessa (Ukraine) in 1814, a secret organization calling itself Filikē Etaireia (Φιλική Εταιρεία) “Society of Friends” was formed with the aim of liberating Greece from the monarchy and autocracy of Ottoman rule. The insurrection was planned for March 25, 1821, the Greek-Orthodox Feast of the Annunciation of Virgin Mary.

Ancient Greece, especially Athens, exerted much inspiration for the revolutionaries. This sense of appreciation for the ancient Greek heritage is sometimes, mostly in jest although the Junta notoriously used ancient Greece as a propaganda tool, referred to as προγονοπληξία (ancestor obsession), a phrase coined by novelist Yiorgos Theotokas, or αρχαιολατρία (worship of antiquity). Revolutionaries named their children after ancient Greeks, Leonidas, Odysseas, Alexander, Pericles, Achilles, Sapho, Kleoniki, and Penelopi. Classical philologist Adamántios Koraís (Αδαμάντιος Κοραής) and others, also European and American philhellenes, contributed intellectually and in some famous cases also physically to the freedom fight (see also Nevila Pahumi’s piece). Korais introduced a standardized purified (from foreign loan words) Greek language, katharevousa, which was close to ancient Attic Greek and koiné, the lingua franca of the Hellenistic and Roman periods, and a journal important for the cultural and intellectual framework of the Revolution, Hermes ho Logios (Ἑρμῆς ὁ Λόγιος), the first Greek journal published. It was issued from 1811 to 1821 in Vienna, lending a national voice to the dispersed Greek communities during the last years of Ottoman rule. Several of the editors were revolutionaries and members of the Filikē Etaireia, including Konstantinos Kokkinakis who was arrested in 1821. Also important for a sense of national unity and ancient Greek heritage shortly before the Revolution was Rigas Velestinlis a.k.a. Rigas Feraios (Ρήγας Βελεστινλής or Ρήγας Φεραίος), editor of a daily Greek newspaper in Vienna, who eventually was tortured and killed as a revolutionary. His most significant political manifesto was a draft constitution from 1797 whereas his perhaps most original work was a chart or map, based on a map of a unified ancient Greek nation, with ancient (and medieval) Greek coins from southeast Europe and a chronology of famous ancient Greek heroes and rulers (also Byzantine), known as “Rigas Charta” (Χάρτα της Ἓλλαδος), printed in Vienna in the late 1700s to help envision a unified Greece. For more on Feraios, the Revolution, and the formation of the modern Greek nation, and a presentation of a collection of revolutionary era materials owned by the Library of Congress, see Nevila Pahumi’s contribution next.

To learn about the Center for Hellenic Studies, its library, collections, and access policy, consult the CHS website and follow its social media posts.

Greek Independence and Philhellenism at the Library of Congress

By Nevila Pahumi, Reference Librarian for Modern Greek

Greek Independence Day is almost upon us! On March 25, 1822 this sunny Mediterranean nation proclaimed its independence from the Ottoman Empire. The road there was long and arduous. But the cause and the great suffering which accompanied it, garnered great sympathy and support across Europe and the United States through the movement known as Philhellenism. The Library of Congress holds a wealth of primary and secondary sources in multiple types of formats in the study and recognition of this historical achievement. This blog post introduces readers to some of them.

The roots of Greek independence go back to the European Enlightenment and the French Revolution. The fight for independence came after centuries of Ottoman rule and oppression, and some of its loudest supporters were in the West. A good place for students of this history is to start with the heroes of the Greek Revolution. This biographical sketch of Rhigas Pheraios, the so-called protomartyr of the Greek Revolution, provides background into the intellectual underpinnings of the movement in the late 1700s.

Rhigas Pheraios (Greek Ρήγας Φεραίος) was a publicist who travelled to Vienna in the 1790s to propagate the Greek cause among the city’s large Greek population. He also intended to ask the French General Napoleon Bonaparte for support. T, Austrian authorities arrested him for inciting rebellion against the neighboring Ottoman Empire. The French Revolution (1789-1799) had stirred up fervor and unrest in young people like him, and he was ultimately executed.

A decade later, a new generation of rebels would pick up Rhigas’ fight, seeking support in Russia. Alexandros Ypsilantes was an army general who organized the Philike Hetairea (Friends Society) to lead the fight for independence which began in Moldavia. As the fighting intensified and Ottoman troops committed atrocities, Western supporters—American, British, French, and German—flocked to Greece and took their voices to the press.

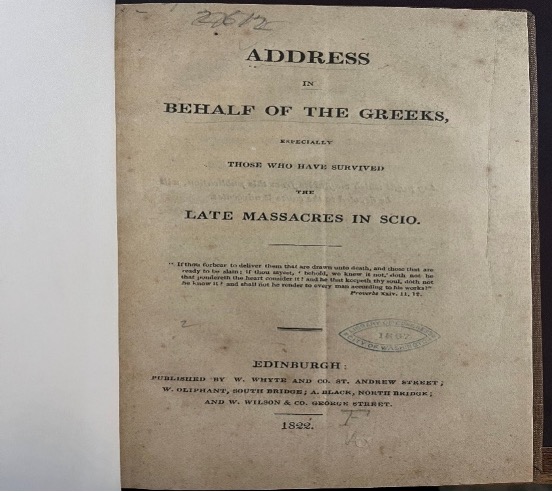

In America, the new city of Ypsilanti, Michigan took on the name after the Greek hero. In Great Britain, sympathizers addressed Parliament and the press, offering testimonies of the fighting and the plight of the Greek people to stir up public support. The following image is a depiction of one such address published in Scotland in 1822, following the massacres in the Greek island of Chios.

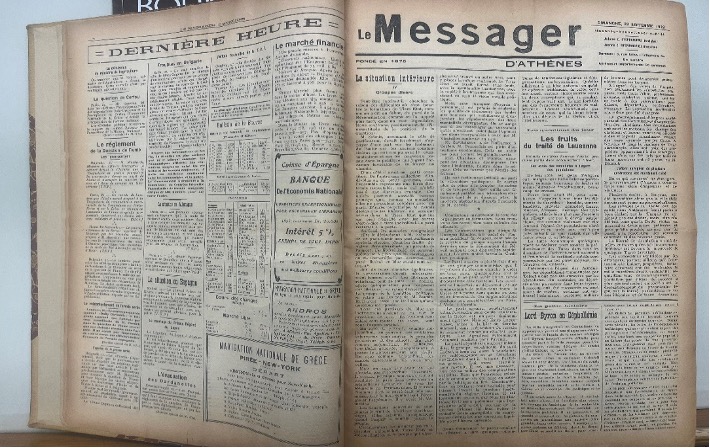

One of the prominent British figures who took up the call was the dashing and brash Romantic poet, Lord George Gordon Byron. Byron himself would die in Missolonghi, Greece in 1823. But the people of Greece never forgot him! Almost a century later, when the country was celebrating its centenary, Greek newspapers, which the Library also holds in the Newspaper and Current Periodicals Reading Room, mentioned him in their commemorations. The next depiction is an article from September 23, 1923 in the Athenian daily, Le Messager D’Athenes, pointing out Byron’s feats and the festivities honoring his contributions to independent Greek in Kephalonia, the Ionian island where he lived for a time.

While the stories of male heros Rhigas and Byron were very compelling, the Greek Revolution was also shaped by courageous and brave women led by Laskarina Bouboulina. This recent Greek acquisition entitled Gynaikes kai Epanastase (Women and Revolution) by Vasilike Lazou tells their stories.

The fighting ultimately stopped in 1832, and Greece became a kingdom soon after. But scholars and artists have not stopped their commentary on the Greek Revolution! In fact, new works have continued to be published since. And Greeks themselves have also carried their celebratory traditions abroad, in communities where they have made a new life.

Among the unique holdings surrounding Greek independence, the Library holds an impressive selection of visual and audio materials attesting to the historical nature of the celebrations across time and space.

For example, the Recorded Sound Reference Center in the Library’s Madison building holds recorded portions of a speech given by Assistant Secretary of State A.A. Berle during Greek Independence Day ceremonies on Mar. 25, 1942. Berle can be heard discussing current political and social issues pertaining to Greece. Interested listeners are advised to make an appointment ahead of time at the Recorded Sound Reference Center. The Science and Technology Reading Room, in the Library’s Adams Building, holds a collection of World War II Greek Independence Day pamphlets, which likewise, have to be requested in advance.

Finally, the Prints and Photographs Reading Room, in the Library’s Madison Building, and the American Folk Life Center possess their own Greek Independence gems. Among them, is a digitized collection of images of Greek Independence Day celebrations in Lowell Massachusetts on March 25, 1988 held in the American Folk Life Center. This next image of a cheerful (if not unruly) chorus of children clad in Greek costume is among the most adorable of the set of twenty five pictures.

Whatever part of this occasion has got you curious: whether it is the tragic Rhigas, the dashing Byron, or the feisty Laskarina Bouboulina and her band of women warriors, feel free to come on into the Library! We’ll help you turn the page. Happy Greek Independence Day.