Gregory Crane

“Its bigger than all of us”

– Gregory Nagy (on many occasions)

Abstract

Greek and Latin are foundational languages in the cultural heritage of humanity as a whole. Students of these languages have an opportunity—and arguably a primary obligation—to make sources in Greek and Latin advance a broader dialogue among civilizations. Such a shift in focus demands a shift in the intellectual culture of Greek and Latin studies, one that looks beyond specialist journals and towards a global audience, that engages not only advanced researchers and library professionals but also student researchers and citizen scholars, and that builds social as well as intellectual connections across stubborn boundaries of culture and of language. These changes are both radical and traditional, and bring the humanities closer to the practices of the natural sciences as well as to the traditional vision of a republic of letters.

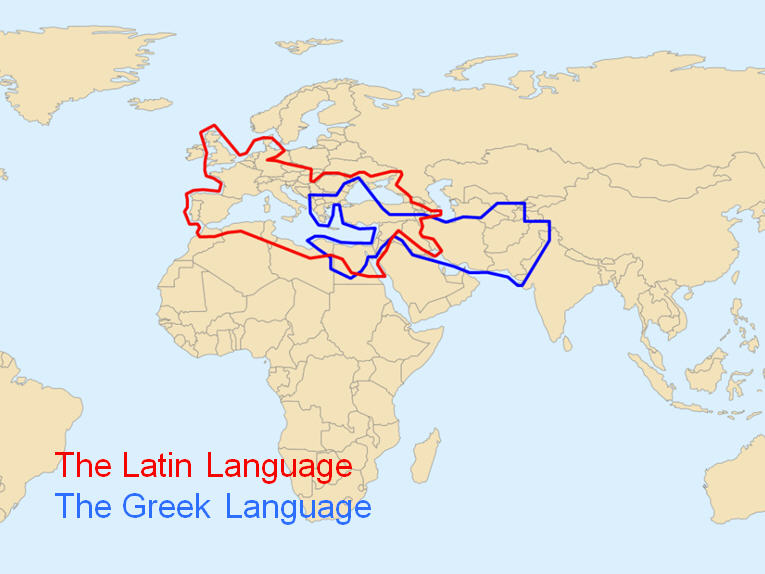

Greek and Latin are poised to play a much broader and dynamic role in the wider intellectual life of humanity. [1] Where the study of these languages has been a symbol, and all too often an instrument, of ethnocentrism and of disengagement from wider society, Greek and Latin are world languages, with corpora far larger and more complex than the tiny secular canon upon which classical studies have focused, and are thus languages in which ideas have evolved and shaped major portions of the world for thousands of years.

Pushed by the need to produce new publications to acquire jobs, gain tenure and win promotion, professional classicists have already begun to fan out and to cover a wider range of Greek and Latin in the publications that they create for one another. But the most substantive developments lie ahead and move far beyond thin networks connecting a small number of research libraries and serving professional students and academics. Where academic publications such as monographs typically sell only several hundred copies, the global net public exceeded 2.3 billion in 2011—one third of living breathing humanity.

We have made extraordinary progress in providing physical access to the human record. At least one hundred million words of Greek and Latin composed before 600 CE survive and have been published in print editions. Most of these printed editions are long out of print and new print editions regularly cost more than US$100 each. The Loeb Classical Library [2] provides the single most comprehensive published collection of Greek and Latin sources available in print, but the five hundred volumes in this series represent only about twenty-five million words of Greek and Latin. Gallica [3] , Google Books [4] , the Internet Archive [5] and many smaller collections have made one or more print editions of every major classical Greek and Latin source available for public download as scanned image books. If we look beyond the classical period and consider all Greek and Latin sources produced through the present, the shift is even more dramatic—an analysis of the first 1.2 million digitized books downloaded from the Internet Archive identified 2 billion words of Latin, the vast majority of which was produced after the Classical period. [6] High-resolution images—better than could be distributed on paper or microfilm—are freely available for thousands of manuscripts, images, papyri or other original sources. [7] An internet public that numbers in the billions has digital access to images representing billions of words.

But progress in digital access only creates the challenge to provide corresponding intellectual access, allowing a global public to understand the sources that they have found. Print technology supported bi-lingual editions, from early modern editions of Greek sources with facing Latin translations through the Loeb and Budé editions of Greek and Latin with accompanying English and French translations that appeared in the twentieth century. In a digital space, new tools such as parallel text alignment and morphological analyzers allow us to use old tools such as translations and lexica in new ways. [8] A new form of philology, derived from corpus and computational linguistics, has allowed us to create wholly new born-digital methods for analysis and for reading support, such as treebanks that record the morphological and syntactic functions of every word in a text. [9] The emerging suite of dynamic methods enables advanced researchers to work with much larger and heterogeneous collections and at the same time allows readers to begin engaging directly with primary sources even before they begin formal training in the language.

Students of Greek and Latin have an opportunity to make the full sweep of Greek and Latin sources intellectually as well as digitally accessible to a global community—not just a canon of secular Greek and Latin sources but thousands of years of human experience that survives in these languages. To do so requires radical reassessment of many of our current practices and a profound reassertion of our most ancient and beautiful commitment to advance as broadly as possible human understanding of the past. Where we have inherited a culture steeped in exclusivity and class privilege, we can create a legacy of openness and cosmopolitan humanity, one that grows stronger as each thread of the human record is more fully defined and woven in with the whole.

To accomplish this goal, the study of Greek and Latin needs to develop a new culture of learning, one that looks outward to the intellectual life of a global society. The relatively small handful of advanced researchers and library professionals cannot translate or contextualize billions of words produced over thousands of years. Increasingly automated systems provide a growing range of tools to aid in understanding but these automated systems provide a beginning, rather than a substitute, for human analysis. We need to engage our students and fellow citizens as collaborators. We need a laboratory culture where student researchers make tangible contributions and conduct significant research. [10] We need citizen scholars to join the citizen scientists who classify galaxies and collect environment data. [11] The crush of data challenges us to realize higher ideals and to create a global, decentralized intellectual community where experts serve the common understanding of humanity.

The Challenge of the Experimental Sciences

The STEM disciplines—science, technology, engineering and mathematics—have posed challenges to the humanities. To some extent, these challenges reflect the perception that STEM majors better prepare students for well-paying jobs. But much of the progress in the STEM disciplines reflects changes in intellectual culture that have nothing to do with economic gain or positivistic notions of scientific knowledge. More than one publication has appeared to defend the humanities and the liberal arts in general, usually stressing the importance of such education for a democratic society. [12] If we shift to the values which proponents of the STEM disciplines propose, the distinctive contributions of humanist education are much less clear.

In March 2010, for example, an article appeared in the Boston Globe that addressed the rising popularity of majors in science and engineering published under the title “At Harvard, re-engineering science: New focus, majors draw in students.” [13] This particular article not only documents a major shift within the home institution of the Center for Hellenic Studies (CHS) but also provides context and advances explanations for the new-found attraction of the sciences and engineering. Harvard illustrates one case where the best-supported programs in the humanities and social sciences compete with the counterparts in the sciences.

In a five-year period, the number of Harvard students declaring science and engineering majors had risen 27 percent, while overall enrollments had remained essentially unchanged. Every new major in the sciences and engineering thus constitutes one fewer major in the humanities and social sciences. The balance remains skewed—even with these increases, less than a third of undergraduates majored in the sciences and engineering. Among students entering Harvard in the fall of 2010, the article reported, “58 percent expressed their intent to major in the sciences, a 52 percent increase from 2005, according to admissions office data. Engineering alone saw a 76 percent growth in interest.”

The article suggests several reasons for the rise of majors in science and engineering, each of which poses a substantial and, arguably, increasingly difficult challenge to the humanities. For now I will summarize these challenges and will return to them later.

First, the sciences are more important than the humanities if we are to understand how the world is changing. The sciences prepare students to win jobs in a globalized world—and students recognized that they had to work even harder than their predecessors to survive. The main things changing in the modern world are science and technology. “These are efforts by a leading liberal arts university to come to grips with the world that is changing around it,’’ said George Whitesides, a chemistry professor who graduated from Harvard in 1960. [14]

This focus upon public impact has continued to grow. As this paper was being written, the author received an email from the National Science Foundation (NSF): “The award referenced above is subject to new NSF reporting rules which require the submission of a Project Outcomes Report for the General Public. This is a new final report that is submitted in addition to your final project report. The Project Outcomes Report serves as a brief summary, prepared specifically for the public, of the nature and outcomes of your NSF-funded project. The report must be submitted within 90 days after the expiration date of your project.” Everyone who receives support from the NSF for any research—however advanced and challenging—is required to think about the broader impact of that research.

Second, the sciences provide a more trustworthy space in which hard work and ability can shine. The web afterlife of the article also suggests another factor for the increasing popularity. The original Globe article was re-published on the “Asian Advantage College Consulting” blog and appeared under a banner “Beat the Asian Quotas!” Whatever the motives of the blog editors, many readers have perceived in this article framed on this blog that the sciences provide an opportunity by which Asian students can overcome institutionalized obstacles to advancing their academic careers. Put another way, the sciences are perceived as providing a better space for merit than are the humanities. The humanities are, in this view, enmeshed in politics of culture and identity. There are certainly historical reasons for this view, with no field having, as we will see, more such historical issues than the study of Greek and Latin.

Third, courses in the sciences have been re-designed to treat students as effective agents who can make active use of scientific data rather than as beginners who are attempting to master 100% of a fixed curriculum to which they must simply adapt. Harvard President Drew Faust, herself a historian of the American Civil War, is quoted as saying: “Science education isn’t just for people who are going to be Nobel Prize-winning scientists. We need to have an education that enables a wide range of students to be excited by the sciences. People who go into policy fields need to understand science. They can’t just say, ‘That isn’t for me.’’’ Another faculty member quoted in the article finds the image of policy maker too humble. According to Douglas Melton, co-director of Harvard’s Stem Cell Institute, “We said, ‘Let’s teach freshmen everything they would need to know about HIV if they were going to be president of the United States.’’’

Fourth, the sciences rapidly put students in positions where they could make substantive contributions and conduct meaningful research of their own. Where the first three arguments build upon quotes from faculty and administrators, this argument draws upon more direct analysis of student experience. The freshman advising system was overhauled to connect students “with research opportunities with faculty as early as freshman year, which professors say help students decide to stick with science. Of students surveyed in 2009, nearly half in the sciences had conducted research outside of class.” The article concludes with a specific example:

Freshman Drew Simon said the new stem cell major and the research opportunities it could bring helped sway him to choose Harvard over Princeton University. His freshman adviser directed him to the right professors, and even though he had no research experience, by his second semester he landed a spot in a lab doing cardiovascular research through Massachusetts General Hospital.

“When you come into Harvard, it can be really daunting, so to be able to be hooked up with that as a freshman is really awesome,’’ Simon said.

This phenomenon goes beyond the anecdotal:

Through a better advising system, more students than ever before are connected with research opportunities with faculty as early as freshman year, which professors say help students decide to stick with science. Of students surveyed in 2009, nearly half in the sciences had conducted research outside of class.

Not every institution may be able to provide the advising support and research opportunities available at Harvard and Princeton, but the examples above illustrate a more general change in the goals of education in the sciences. Significant experience, both independent and as part of a larger group, is now expected from ambitious undergraduates in the sciences. The prestigious NSF Graduate Research Fellowships provide the following guidelines for those writing letters of recommendation. They must comment on the candidate’s potential to “conduct original research,” “communicate effectively, work cooperatively with peers and supervisors,” and “make unique contributions to his/her chosen discipline and to society in general.”

The first criterion used to evaluate applicants is “intellectual” merit. “The intellectual merit criterion includes demonstrated intellectual ability and other accepted requisites for scholarly scientific study, such as the ability to: (1) plan and conduct research; (2) work as a member of a team as well as independently; and (3) interpret and communicate research findings.” [15]

The guideline continues: “Panelists are instructed to consider: the strength of the academic record, the proposed plan of research, the description of previous research experience, the appropriateness of the choice of references and the extent to which they indicate merit, and the appropriateness of the choice of institution for fellowship tenure relative to the proposed plan of research.”

Every leading candidate for graduate support from the NSF must, therefore, have an established track record in independent research and must also be able to work collaboratively as part of a larger team. How many graduating seniors with degrees in the humanities come from programs that prepare them for the criteria described above?

Research in the humanities as a whole and particularly in classics has been, and for the most part remains, deeply hierarchical, with few opportunities for anyone to publish before they are advanced graduate students. Anecdotal evidence suggests that undergraduate research is much less prominent in the humanities than in the sciences, with humanists focusing upon single authored publications that assume extensive knowledge of technical terms and intellectual trends and that offer no substantive opportunities for student contribution.

A random sampling of university administrators has expressed to the author excitement at the notion that they might support undergraduate research in the humanities as well as the social and natural sciences. One prominent, forward-thinking classicist, hearing about possibilities for undergraduate research in classics, grew more and more perplexed until he turned to a biologist and asked whether undergraduates contributed substantively in her research area. She reported that she thought he was joking—her pharmaceutical industry employer assiduously sought out the best undergraduates for summer internships in substantive projects.

At least one fairly general data-point is available. A tenure track job description for a position in Greek and Latin at Tufts University, published in 2009—a terrible year for the US economy and an even more terrible year for jobs in Classics than usual [16] —concluded with the following statement: “We especially welcome candidates who can support contributions to and original research by undergraduates as well as MA students within the field of classics.” Translated into more direct English, this statement meant: “We leave ourselves the legal ability to hire someone who cannot support contributions to and original research by undergraduates as well as MA students if absolutely necessary, but this is what we want.” We expected, given the even more desperate than usual job market, that we would hear quite a bit about undergraduate and MA-level research in the cover letters.

Roughly 180 applications were received, a selection that included most, if not all, active Classics PhD programs within, and many beyond, the English-speaking world. This pool thus provided, in effect, a survey of recently trained PhDs. Of this group, less than five addressed this leading statement and of these, most understood undergraduate research as clerical work. Out of the 18 applicants interviewed, only a handful could respond substantively when pressed on this topic. Most of those asked about “contributions to and original research by undergraduates as well as MA students” squirmed and looked uncomfortable. Those few who could respond did so because they had developed ideas independently, despite, not because of, the training that they had received.

Similar lack of experience with the possibilities of undergraduate and graduate student research was expressed by many of the participants who attended a summer 2012 National Endowment for the Humanities (NEH) Institute, Working with Text in a Digital Age. [17] This Institute supported 23 humanists (out of an applicant pool of 80) for three weeks at Tufts University. As participants summarized what they had learned, graduate students and faculty alike singled out the most surprising thing as the degree to which undergraduates could immediately work with primary sources and begin contributing to our understanding of long studied subjects. Three years after the 2009 job search, “digital humanities” had emerged as a trendy topic [18] but it was understood to describe a sub-discipline in the humanities or a set of techniques for generating more single authored articles and books. [19]

Defenders of the humanities claim a special role in training citizens for a democratic society and often have deeply felt convictions about democratizing knowledge and including new voices. The mainstream of humanities research has, however, focused upon virtuoso scholarship, published in subscription publications to which only academics have access, and composed for small networks of specialists who write letters for tenure and promotion and who meet each other for lectures and professional gatherings. Students in the humanities remain, to a very large degree, subjects of a bureaucracy of information, where they have no independent voice and where they never move beyond achieving goals narrowly defined by others. The newly re-engineered sciences have reorganized themselves to give students a substantive voice in the development of knowledge and to become citizens in a republic of learning. The STEM disciplines certainly have not fully realized these lofty ideals but they are far ahead of most of their colleagues in the humanities and in Greek and Latin studies.

Humboldt’s Vision

The integration of learning and research may be, in practice, an innovation, but it is not a new idea. Two hundred years ago Wilhelm von Humboldt articulated this model of the university when he led the development of the University of Berlin, which now bears his name and that of his brother, the naturalist Alexander von Humboldt. Wilhelm von Humboldt (1767-1835) was a Prussian aristocrat and linguist, who was also in large measure responsible for designing the Prussian educational system, which, in turn, provided the most important model for higher education in the United States. Every research university in North America traces much of its structure and philosophy back to Humboldt.

Universities were not a new idea in Germany at the start of the nineteenth century. Friedrich Wolf had helped to define modern Classical scholars at the nearby University of Halle, which had been founded in 1502. In 1817 at Goettingen (founded in 1734), Edward Everett, the first Eliot Professor of Greek at Harvard, Governor of Massachusetts, Minister to the Court of Saint James, Senator, 1860 nominee for Vice President and the notable orator who gave the official, if less renowned, Gettysburg Address, began his career by being the first of many Americans in the nineteenth century to receive a PhD from a German university. The University of Leipzig (founded in 1409) in neighboring Saxony was arguably the richest and most prestigious university in Germany during the eighteenth century. Advanced research was also not an innovation in Berlin, where the Electoral Brandenburg Society of Sciences (now the Berlin-Brandenburg Academy of Sciences) had been founded a century before in 1700.

The idea of a research university was, however, new. It built upon the Enlightenment and the intellectual climate that Frederick the Great had fostered. Challenged to answer the question “What is enlightenment?” Kant had, in 1784, quoted Horace: Sapere aude! “Dare to be wise! Have the courage to use your own intelligence!” [20]

The re-engineering of science described above may be innovative in the short run but it is also deeply traditional, following a path that Humboldt had articulated more than two hundred years before the Globe article. The pre-professional thread in the article and the notion that the university should too directly serve the changing needs of society may not be consistent with Humboldt’s vision but he captured clearly the vision of student and professor alike as servants of Science with a capital ‘S,’ and of a constructive, even joyful, culture of collaboration.

In an incomplete essay composed in 1809/1810 but published a century later, Wilhelm von Humboldt wrote “about the internal and external organization of institutions of higher learning in Berlin.” [21] Humboldt’s essay begins with an aggressively idealistic model in which all institutions of higher learning—both the established Academies of Science and his new university—contribute knowledge not for some particular end but as an end in itself and as a contribution to the spiritual and moral education of the nation. [22] The goals of the university are, in Humboldt’s view, objective knowledge and internal intellectual and moral development, with disembodied knowledge and internalized character each strengthening society as a whole. Only insofar as the knowledge remains the primary object can knowledge be properly understood and appreciated. [23] The pursuit of knowledge is not a grim assembly line but an expression of human freedom and an object of constantly renewed passion. Institutions of higher learning support individual difference and freedom to create a harmonious society whose members take delight in their several and mutual achievements, not just because those achievements may be useful to their own work but because those achievements serve the ultimate goal of advancing learning.

Humboldt describes the intellectual climate of mutual delight that must shape both academy and university. “The spiritual work of humanity only flourishes insofar as it is a collective work. And that does not simply mean that one provides what the other lacks but that the successful capacity of the one inspires the others.” All must see that capacities previously split among many different individuals become an emergent, harmonious force that is greater than the sum of its collective components. “The internal organization of these institutions must elicit and support an uninterrupted, constantly self-renewing, but also unforced and impartial collective work.” [24]

Education in the university, however, represents for its students a sharp break from the training previously received from schools. In the university, the advancement of knowledge is the primary object. Students must arrive at the university no longer dependent upon set curricula but prepared to follow their own independent passion for the advancement of knowledge. This passion is only possible insofar as students in the university see knowledge as a living entity that is constantly developing and to which they can contribute.

It is a characteristic of institutions of higher learning that they treat knowledge (Wissenschaft) always as a problem that is not yet completely solved and that they thus always remain engaged in research, while schools are engaged with, and teach, information as ready and completed to be mastered (Kentnissen). The relationship between teacher and student becomes thus something completely different than before. The teacher is not there for the student. Both are there for knowledge. His [the teacher’s] business depends upon their [the students’] presence and would, without them, not proceed nearly so well. He would, if they did not assemble themselves around him, seek them out, so that he could more nearly approach his goal through linking the well-practiced, but also therefore more one-sided and indeed less dynamic power with less-developed and still unaligned, power that strives mightily in every direction. [25]

Humboldt concludes this portion of his argument by seeing in institutions of higher learning “nothing else than the spiritual life of humanity.” [26] A substantial portion of his argument revolves around the role of the State (in particular, the Kingdom of Prussia) and the university, with an insistence upon independence and intellectual freedom as essential to the advancement of knowledge.

For Humboldt, objective knowledge is not an end in itself because it is also a means for the development of individuals and thus of the state (or, as translated here, “society”) as a whole. Knowledge is not the “heaping up of dead collections” (die Anhäufung todter Sammlungen) but an object that draws upon and develops the mind and soul of humanity.

As soon as one stops to pursue knowledge on its own, or imagines that knowledge is produced not from the depths of the spirit but from collection broadly organized within itself, then everything is irreparably and forever lost—lost for knowledge, which, if this process long continues, reaches a condition where it leaves behind words as an empty husk, and lost for society (der Staat). For only knowledge that grows from within and that can be deeply planted within, also transforms character. For society, as for humanity, the question is less of knowing and speaking than of character and action. [27]

A university must, Humboldt concludes, foster every capacity of its students and develop within them a love of learning so that “understanding, knowledge and spiritual creation win their attraction not through external circumstances but through their inherent precision, harmony and beauty.” [28]

Humboldt would not have supported everything in the twenty-first-century university. In particular, he argues forcefully that universities not simply serve the material needs of the state and that they not simply convey received knowledge or focus upon technical training. The traditional large introductory lecture classes built around textbooks would, in Humboldt’s model, be more suited to the school than the university. The shift away from rote memorization to more hands-on laboratory work, individual projects, and the development of organic intellectual capacity are one attempt to address the depersonalized factory model of the large lecture class and a step towards Humboldt’s model.

The re-engineering of science described above has enjoyed success not because of the broad statements of self-serving faculty or administrators. It has enjoyed success insofar as it has provided for anxious students particular space within a complex intellectual ecosystem where they could quickly develop their own identities and voices, and where they could cultivate as well a passion for building on, and contributing to, the evolving network of human ideas. The Republic of Letters has become a republic of science, a republic that has been more successful in engaging a wide audience as partners.

Two particular threads help to document this phenomenon. First, the NSF supports two programs under the rubric of Research Experiences for Undergraduates (REU-s). One program supports projects designed primarily to support undergraduate research while another allows those with existing NSF grants to receive extra money to integrate undergraduates into their already funded projects. A glance at the 2012 contact page for REU-s [29] shows that the program is designed to support the full range of NSF-funded disciplines. REU-s are a standard component of NSF projects and reinforce the culture of independent research, separate from any particular course, that the Globe article cites as a key feature of emerging science.

The NEH has no program designed to foster undergraduate research. Of course, with a budget forty times larger than that of the NEH, [30] the NSF can accomplish quite a bit more. Nevertheless, the NEH review process for other projects reinforces the perception that humanists not only do not currently support undergraduate research but that they are hostile to the concept. Where Humboldt saw in students a source of energy and of new perspectives, a substantial percentage of humanists, arguably a significant majority, are eager to get away from their students because their actual research is only accessible to advanced researchers. Such a perspective does not reflect so much upon the individual humanists as upon the traditions of humanities research inherited from print culture.

Second, citizen science—or, more specifically, citizen cyber science—has emerged as a significant force, initially to do work for scientists and more recently to help define the work that the scientists themselves do. While citizen science may begin as a way to draw upon large and largely anonymous crowds to address mostly mechanical tasks set by professional scientists, it can evolve into a much more balanced interaction between professionals and the wider public. In its fullest form, scientists and members of the broader public collaborate to identify and to design research problems. Of course, this interaction already happens in some measure where government funding supports research and funding agencies must make a case to a voting public to justify their support. But citizen science nonetheless creates opportunities for a more direct and nuanced conversation.

Citizen scientists have for years played a critical role in classifying galaxies and in environmental studies. The 2012 London Cyberscience Summit [31] included presentations on citizen contributions to research projects not only in Europe and North America but in Asia and Africa as well, covering topics such as ornithology, forest management, and botany. Citizen Science has, however, begun to emerge as a research topic in its own right and not simply as an instrument for particular efforts. A substantial number of presentations went beyond particular projects and described more general topics about citizen science such as “e-infrastructures for citizen science”, “citizen, science, education and technology,” and “introduction to extreme citizen science.”

Ngoni Munyaradzi, University of Cape Town, presented on “the transcription of Bushman Historical Text” and Stuart Dunn of King’s College on “community-source structured metadata of English place-names”, but no humanities faculty members from European or North American universities presented at the 2012 Citizen Cyberscience Summit. Tenure stream faculty at established universities in Europe and North America do not yet, for the most part, see such broadly collaborative work as advantageous. Humanists have made use of crowd-sourcing for data entry (including the Ancient Lives [32] project, which challenges members of the public to help transcribe papyri), but the crowd metaphor, with its image of faceless masses solving tasks too tedious for the expert, reflects a stage of development that precedes—and may evolve into—true citizen science, where contributors have an identity and a voice in shaping the research agenda. [33]

We can see the challenge that humanists face in their attitudes towards Wikipedia—the greatest citizen science project so far and probably much more important to the future of the humanities than anything accomplished by professional humanists so far in the twenty-first century. It is still common to hear classicists speak dismissively of Wikipedia coverage in their field and, indeed, to hear in this shared dismissal a statement of solidarity. Articles on classical subjects in Wikipedia may well lag behind many extraordinarily articulate subjects on complex subjects in mathematics, biology or physics. Perhaps some humanists would argue that Greco-Roman culture is a more challenging subject than the sciences. Others—including the author of this piece—believe that any relative weakness of Wikipedia articles reflects the weakness in the intellectual community interested in classics outside of paid specialists. If our Wikipedia coverage lags behind that of equally, if not more, complex subjects, that reflects upon the failure of those of us who are in fact specialists in our duty to advance the broader life of society and to engage our fellows as colleagues.

One could perhaps argue that the passages from Humboldt quoted above are quite general and did not apply also to humanists. In an often-quoted passage from a separate essay, “On the task of the historian,” Humboldt speaks more specifically to humanists:

If we want to identify one idea which through the whole of history is visible in ever broader effect, if any [idea] proves the often contested, but even more often misunderstood perfection of all mankind, it is the idea of humanity, the struggle to remove the hostile boundaries which prejudices and biased perspectives have placed between human beings and to treat all of humanity without regard to religion, nationality, or color, as one great, closely related family, as a single whole for the achievement of a single goal, the free development of individual power. This is the final, external goal of sociability at the same time the inborn inclination of human beings to the unconstrained expansion of their destiny. [34]

Clearly, Humboldt’s vision has its roots in the Enlightenment and particularly in the ideas fostered—however imperfectly—by Frederick the Great and Berlin intellectual society of the eighteenth century. But those who understand the immense prestige that Greek culture enjoyed at this point may also hear in this an echo of the funeral oration, attributed to Pericles, and its idealizing vision of Athenian democracy: “To sum up: I say that Athens is the school of Hellas, and that the individual Athenian in his own person seems to have the power of adapting himself to the most varied forms of action with the utmost versatility and grace.” [35]

It is easy to point out how far short humanity—both in the United States and in Europe as well as in imperial Athens—fell from these ideas in the nearly two centuries since Humboldt composed these lines. In 2012, a monument marks the spot next to the Opera, across the street from the central building of Humboldt University and in sight of the statues honoring both Wilhelm and Alexander von Humboldt, where Nazis, students and faculty among them, burned books. Jack-booted militarists from various regimes goose-stepped past the university up and down Unter den Linden– as they paraded in every European and North American nation at some point in the past two centuries. Kings and idealizing socialists alike used violence to stem dissent. It has been easy to despair and to dismiss as failures the Enlightenment ideals that Humboldt and others sought to embody in institutional form.

Two centuries later, however, kings, Nazis, and Communists have come and (at least for now) gone. The natural and life scientists still speak of Science with the capital S and of serving the needs of a global humanity that seeks physical health and material prosperity in a limited and endangered environment. Cynical lawyers still speak reverently of the Law—often with all the more passion insofar as they understand the harsh limits of the world and the dangerous potential of humanity. To what extent can we in the humanities—and especially those of us who study the Greco-Roman world—answer the aspiration, and implicit challenge, articulated by Humboldt?

Science, Wissenschaft and the Humanities

The original University of Berlin included Greco-Roman culture among its core subjects and, in 1811, a year after Humboldt had composed his vision of the university, it recruited as one of its founding professors August Boeckh, who was, along with Gottfried Hermann, the most influential classical philologist of his generation. Unlike Hermann, who emphasized language as the center of classical philology, Boeckh followed in the intellectual tradition of Friedrich Wolf and saw philology as a broad discipline that encompassed not only language but also the Greco-Roman world upon which our sources shed light. In 1822 (a year after Humboldt’s essay on the duty of the historian quoted above), in his annual Latin oration celebrating the birthday of Friedrich Wilhelm III, Boeckh described the object of philology as an “understanding of the ancient world as a whole, both historical and philosophical.” [36] For Boeckh, this meant understanding the ancient world both from the material and textual record. No classicist was better poised than Boeckh to realize Humboldt’s vision of history as an instrument to unite humanity. Classical philology in particular and the humanities in general, however, have not been able to realize Humboldt’s vision so fully as have the sciences. At least two factors are at work.

First, classics and the humanities in the English-speaking world face a challenge posed by the distinction between science (which, as a single term in English, primarily describes the natural sciences) and Wissenschaft (which includes not only the natural sciences but also the humanities, life and social sciences). In a pre-industrialized age, this separation of the humanities from the rest of the sciences may have been an assertion of intellectual hegemony, as the extraordinarily important role of textually based discourse shifted from religious controversy into secularized topics (such as the Greek and Latin canon).

If the independence of the humanities from science was an advantage in the past, the semantic distinction of English has had a terrible effect in the twenty-first century. In the industrialized nation state, with its dependence upon technological and scientific research for the economic prosperity, the military security, and the biological well-being of its population, the natural and life sciences enjoy an inherent advantage over the humanities. This advantage accounts in large measure for the fact that the US NSF has a budget 40 times larger than the US NEH. More significantly the modest NEH funding must work in isolation—humanists cannot directly draw upon, or participate within, NSF programs.

Not all disciplines within the NSF flourish equally, however, and support for political science research has been under political attack in 2012 and recent years. The so-called STEM fields (science, technology, engineering and mathematics) have been identified as strategic and receive particular support. Nevertheless, even if the amount of funding ear-marked for the humanities within a combined NEH/NSF were the same, humanists could directly collaborate with digital infrastructure projects in much more heavily funded fields such as biology or physics, drawing upon shared services rather than developing their own infrastructure in complete or relative isolation. At the present time, the NEH has no serious funding to support the expensive infrastructure necessary to support learning and research in a digital age. [37] Regular NEH grants rarely exceed US$350,000 while small NSF grants can reach US$500,000, medium grants regularly exceed US$1,000,000 and large grants regularly contain many times this figure. The NSF invests tens of millions of dollars within infrastructure projects in various fields.

The separation of the NEH from the NSF also keeps humanists isolated—some might argue protected—from the cultures of decentralized research and undergraduate participation prominent in the NSF world. If connected to the NSF, humanists would immediately be able to draw upon programs for undergraduate education such as the REU-s mentioned above, where marginal support could have a major long-term effect upon intellectual society.

Humanists in continental Europe do not have this structural problem. In particular, German Humanists can draw upon the German Research Foundation (DFG) [38] and the Federal Ministry of Research and Education (BMBF) [39] . Where the NSF Directorate for Computer and Information Science and Engineering can collaborate with other NSF directorates but not with the NEH, German computer scientists can, in Germany, pursue careers exploring the applications of information technology within the Humanities as well as within biology, physics and other natural sciences. Germany is uniquely positioned to support the evolution of the humanities within a digital world.

Nevertheless, philologists, if not humanists as a whole, in Germany have also failed to realize Humboldt’s vision of the university and have remained vulnerable to the criticisms of the humanities implicit in the “Re-engineering Science” piece discussed above. This reflects at least two distinct processes in the tradition of classical scholarship in particular, each of which ran counter to the larger currents of scientific research.

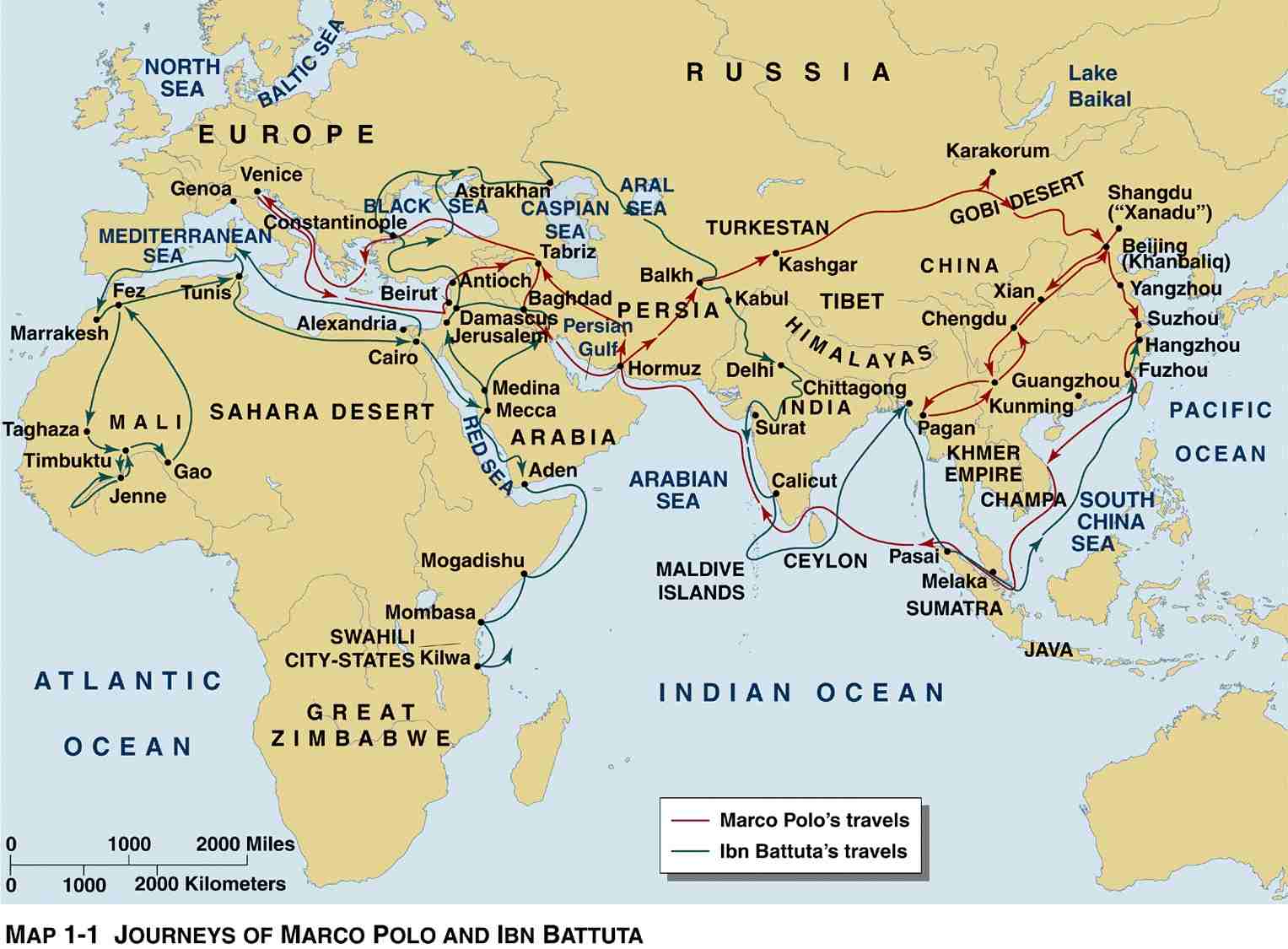

The first process consisted of an increasing ethnocentrism that used the past to justify an exclusive claim to cultural authority. This process can be traced back to early modern humanism in general and to Martin Luther and the Reformation within Germany. Early humanists such as Dante had built upon an intellectual tradition that was Mediterranean rather than European, reflecting both the territorial space of the Greco-Roman world and the direct indebtedness to Arabic scholarship for the transmission and interpretation of Greek culture. For Aquinas Aristotle may have been “the philosopher” but for the twelfth century Muslim author Ibn Rushd (known in the West as Averroes) he was “the commentator.” Dante named Averroes along with the great pagan philosophers, situating them all in “the place that favor owes to fame” in Limbo. Aristotle, Euclid and Galen re-entered Western European thought via translations into Latin not from Greek but from Arabic translations of the original, during the great translation movement from Arabic into Latin from c. 1200 to 1400. [40] The first printed edition to cover Aristotle’s Poetics was not the Greek original or even Thomas of Moerbek’s Latin translation of the Greek, but rather Hermannus Alemannus’ translation of Averroes’ Commentary on the Poetics.

As knowledge of Greek began to reemerge in Western Europe, however, scholars shifted their focus to the Greek sources themselves. Martin Luther and the Reformation as a whole also turned away from immediate tradition and emphasized translations from, and study of, Greek original sources rather than the Latin Vulgate, much less Islamic Arabic sources. A connection with Greek, whether directly or by direct translations, became associated not only with scholarship but also with salvation. Whatever side of the Reformation scholars found themselves on, knowledge of Arabic and of debts to the Islamic tradition were the universal casualties, as Greek, Latin, and Hebrew emerged as the three hegemonic historical languages.

In the United States, at least, that legacy remains firmly entrenched through the present: according to figures published by the Modern Language Association (MLA), in 2009 Greek and Latin accounted for more than 75%, and Greek, Latin, and Hebrew accounted for more than 95% of enrollments in all historical languages. Enrollments for various forms of Latin, classical Greek and Hebrew amounted to 32,000, 22,000, and 13,000 students. [41] Only 285 students were listed as studying classical Arabic, with 483 and 202 enrollments attributed to classical Sanskrit and classical Chinese. When we move from the Renaissance big three of classical Greek, Latin, and Biblical Hebrew to other, less commonly studied languages, we drop two orders of magnitude, from the tens of thousands to hundreds of enrolled students

Second, students of Greek and Latin shifted their focus away from texts critical to Judaeo-Christian religious thought and towards a canon of pagan Greek and Latin sources. In this, the study of Greek and Latin followed a more general trend within the Enlightenment away from religious dogma and towards individual reason. At the same time, the attempt to liberate reason narrowed the focus of those who studied Greek and Latin. When, in 1777, Friedrich Wolf (1759-1824) enrolled himself at the university of Goettingen as “’a student of philology,’ he was the first person to describe himself as such not only at Goettingen but at any German university. [42] Christian Gottlob Heyne (1729-1812), the most prestigious classicist of his time, rebuked the young Wolf for asserting study of philology, a subject that did not exist. More generally, he informed Wolf that there were no more than five or six jobs for classical studies in all of Germany—Wolf must train himself in either theology or law. But Wolf persisted:

… he looked not for bread, but for fame. Not that he was well off, but that his liking for classical studies was so strong, he was ready to make sacrifices to gratify it. Were it on account of the greater intellectual freedom, he vastly preferred these studies to theology. No philologian was branded as a heretic for holding singular opinions. For an instant Heyne was surprised out of his official reserve, and exclaimed, “Freedom! Where is freedom to be found in this life? The young must obey.” [43]

A generation later, while Heyne and Wolf were still alive, Humboldt would respond to this authoritarian mindset and assert that “loneliness and freedom” [44] as fundamental to the pursuit of Wissenschaft and to his vision of a university.

But freedom from theological constraint also contributed to a bias against the study of Christian Greek and Latin sources. This bias was particularly strong in England, where the advancement of knowledge was, at least in the nineteenth century, far less developed as an object of learning than in Germany. In his 1875 biography of the French classicist, Isaac Casaubon (1559-1614), considered by many to be the finest Hellenist of his day, Mark Pattison saw in Casaubon’s attachment to Hebrew and to Christian authors an embarrassment that required apology:

Casaubon’s want of classical feeling limited his pleasure in the pure classical writers. The higher accents of Greek poetry and speculation he could not catch. What stirs his soul is Christian Greek, e.g., S. Chrysostom, whose ‘Epistula ad Stagirium’ excites him to rapture. Of the canonical books, the Hebrew psalter is a constant companion, and never fails to move him. … He is carried away by the enthusiasm of St. Paul. Reading 2 Cor. 4.17 ‘our light affliction,’ etc., he exclaims: ‘Divine words! Paul of all writers I could think wrote not with fingers, pen, and ink, but with pure emotion, heart, bowels! Take any epistle of Paul, e.g., that to the Philippians, and dwell upon it; what glorious passages, what glowing vehemence of language!’ … It is almost a paradox that this most successful and most thorough interpreter of the classics, should have been a man who was totally destitute of sympathy for their human and naturalistic element. [45]

For Pattison, Casaubon’s love of Christian Greek and of Hebrew was not a strength or evidence of wide learning. Rather Casaubon’s affection for these sources was a defect in taste and proof of aesthetic, if not moral, limitations, for which he, as Casaubon’s biographer, had to account if he was to give Casaubon his due measure of respect. Nor was Pattison writing as a twenty-first century academic, for whom any religious feeling seems a failing in reason and a scandal. Whatever Pattison’s personal beliefs, dislike of the Catholic Church and clergy runs as a thread throughout Pattison’s biography, appealing to English pride in its own church. Nor was Pattison an opponent to the advancement of learning as a primary goal of the university. A biographer of Friedrich Wolf as well, Pattison was an admirer of German Wissenschaft and a critic of contemporary Oxbridge academic culture.

Students of antiquity thus increasingly restricted their intellectual focus, ultimately concentrating on a relative handful—perhaps ten percent—of the Greek and Latin sources that lived up to principles established in the eighteenth century. Generations of scholars clustered within a tiny textual space. The barrier to scholarship became so steep that Humboldt’s vision of student and instructor alike serving the advancement of knowledge was simply not a practical option. The narrow focus on a tiny canon made it almost impossible for classicists within Germany to realize Humboldt’s vision.

The author’s own informal conversations with German classicists revealed that, in fact, advanced undergraduates and MA-level students did regularly contribute to some research projects but that there was not yet any mechanism by which to identify their particular contributions. More than one German researcher comprehended the challenge and expressed enthusiasm at such collaborative work and an opportunity to realize more fully Humboldt’s vision (whether Humboldt was mentioned or not). In the United States, British cultural influence compounded the inherent difficulty of the subject.

Classical Studies in the United States and Oxbridge Influences

While our conscious attitudes have changed radically since the nineteenth century, practices that took shape more than a century ago still shape our assumptions about how we study Greek and Latin and who can have a significant voice. The study of Greek and Latin largely—and increasingly—represents an antithesis to Humboldt’s vision of the university. Students take courses and are graded on how well they follow set curricula. They cannot expect on a regular basis to contribute to our understanding of the Greco-Roman world. Research universities in the United States may have followed Humboldt’s model, but curricula in Greek and Latin evolved, instead, from nineteenth century educational traditions in which the study of Greek and Latin were mechanisms to establish membership in an élite class and to achieve access to careers of privilege. This heritage still shapes the underlying assumptions and forms of our curricula.

Few faculty members teaching Greek and Latin would defend the assumptions on race, class, or gender that many of their nineteenth century predecessors openly espoused—many such opinions would now violate civil rights laws and provide grounds for dismissal even of tenured faculty. But if our ideas have developed, the practices underlying the study of Greek and Latin still owe much to social structures and habits as they took shape in the nineteenth and twentieth century. Those who teach Greek and Latin often have deeply held convictions about democratizing knowledge and about reaching new and broader audiences. In creating new curricula about the Greco-Roman world that do not require knowledge of Greek or Latin, they have made concrete steps to transform our relationship to the academy as a whole. But in so doing, we have created a group that can have, at least with the technologies of print, no significant access to Greek and Latin sources in the original languages. The English-language classical civilization courses and majors that have allowed many departments to survive into the twenty-first century are tolerable in part because students were never expected to contribute much anyway.

The study of Greek and Latin maintains a sharply hierarchical culture of knowledge that goes well beyond the difficulties of the field. Our most earnest aspirations to democratize knowledge of the Greco-Roman world can also mask assumptions about possible roles that non-specialists can fill. An earlier section of this paper reported that in the early twenty-first century no PhD-granting departments of classics seemed to have trained its students to support an intellectual culture where undergraduates and MA-level students could make original contributions to, or conduct significant research for, the understanding of Greek and Latin. Interviews with rising classicists and conversations with established faculty from the English-speaking world suggest that such decentralized and collaborative research was not only unknown but also unfathomable and unsettling. Anonymous reviews for NEH proposals that featured undergraduate collaborators were openly hostile. Where German faculty found it easier to imagine students as collaborators, English and even American classicists, in more than one case, dismissed the idea. Such a different attitude reflects a profoundly hierarchical, even in part anti-intellectual Anglo-American mindset that associated knowledge of classical Greek much more closely with class privilege and imperial power.

Where Humboldt saw in academic study a shared pursuit of knowledge to which student and instructor alike were subordinate, the study of Greek and Latin became an instrument by which to demonstrate, and to achieve, participation in a white, male class that dominated all women, members of their own society without the same advantages, and all foreigners. Departments of Classical Studies in the United States and elsewhere have labored to move beyond this tradition and have introduced new critical perspectives and have developed curricula for students who had not had the privilege to study Greek and Latin.

An 1856 book by John William Donaldson, entitled Classical Scholarship and Classical Learning, [46] illustrates a number of historical legacies that shape the study of Greek and Latin to this day and that are in implicit or explicit conflict with the model of intellectual life espoused by Humboldt. The study of Classics has still not fully overcome its legacy.

Donaldson explicitly documents the association between Greek and Latin on the one hand and imperial and class privilege on the other. He argues, for example, for the value of a Classical education as an instrument to choose men who could impose British rule, especially in India:

The able and eminent persons, who framed the scheme for the civil service examination, had no wish to send out to India clever smatterers, feeble bookworms, scholastic pedants, and one-sided mathematicians; but to select the most energetic and vigorous young men from the crowds who were likely to offer themselves as candidates for a share in the administration of our most important satrapies (p. 77).

Within England itself, the study of Greek and Latin prepares the upper classes to lead their social inferiors. The summary of Donaldson’s book states one aspect of progress that might surprise modern readers.

“Liberal education of the upper class is the great panacea for present and future evils” (p. x). This summary from the introduction points to the beginning of a long discussion of Greek, Latin, and the importance of education, a discussion that concludes with the following aspiration: “I hope I have convinced my readers that, while we are able to appeal to a considerable list of learned writers more distinguished in many ways than their predecessors, classical scholarship is still, what it was, a characteristic of the higher classes in this country” (p. 156).

Donaldson devotes a substantial portion of his argument to denigrating German scholarship, particularly the notion that German classical scholarship leads the world. In part, Donaldson enumerates the achievements of British researchers but he goes further, denigrating the education German classicists receive and diminishing the moral implications of scholarly production. Donaldson distinguishes between the learned writer and the scholar. The scholar is:

… a person who has learned thoroughly all that, ‘the school’ can teach him. The epithet ‘scholarlike,’ or, as some of our contemporaries prefer to spell it, ‘scholarly,’ suggests to our minds the idea of complete and accurate knowledge, as opposed to a smattering of general or diversified information. When honest Griffith says of Wolsey: ‘From his cradle / He was a scholar and a ripe and good one,’ we at once accept the phrases as denoting a certain kind of knowledge, proceeding from early training, and afterwards completely appropriated, digested, and matured. Having regard to the results produced by the teaching of our best English schools, we expect, when we hear that a man is an elegant and accomplished scholar, that he has become familiar with all the very best Greek and Latin authors … We should perhaps be disappointed, if we did not learn on inquiry, that he can write Greek and Latin, both in prose and verse, with idiomatic correctness and finished excellence (pp. 149-150).

Two features characterize the scholar. First, the scholar has internalized from his school not only content but also taste and sensibilities. Second, this deep internalization of knowledge, skills and sensibilities is only possible to those who engage in such study from an earlier stage. Individuals may indeed become “learned writers” at a later stage in life, but such learning is, for Donaldson, clumsy and an object of condescension, if not scorn. One can become a learned writer but only as an opsimathês—Donaldson here alludes to, without bothering to mention, the Greek author Theophrasus who mocks the “late-learner.” Donaldson describes the opsimathês as

… a self-taught man who has acquired his knowledge late in life. Whatever his own resources enable him to do, he will always exhibit a marked deficiency in regard to those particulars, which especially distinguish the well-trained scholar. If, which is rarely the case, he contrives to be accurate, he is almost always conspicuous for unwieldy and cumbrous diction. If his knowledge is really extensive, it is like an undisciplined host, which makes an attack in close column, but cannot charge in line. … Above all, if he attempts to disport himself in classical composition, nothing can exceed the infelicity of the effort, except perhaps the respectful admiration with which it is regarded by the author himself and his friends (p. 151).

The highest achievement of scholarship and the accomplishment on which Donaldson bases his praise of British classics is the ability to compose Greek and Latin prose and verse.

Donaldson singles out for praise two Germans, Gottfried Hermann (1772-1848) and Karl Lachmann (1793-1851), but argues that these classicists are not typical Germans:

By selecting these two specimens of German scholarship we should indeed adduce the most favourable instances which could be found, but should not exemplify the general character of the German philologer. For, in their activity of mind and body, Hermann and Lachmann came nearer to Englishmen than 99 out of 100 Germans; and both of them made more progress in classical composition than any Gelehrten of their time. In a word, Hermann and Lachmann deserved to be called scholars, and wanted nothing to give a perfect finish to those accomplishments for which nature had so well qualified them, except the advantages of an English education, and the competition of an English University (p. 157).

Of course, they could count as scholars—but not among the best scholars:

For, while the Latin elegiacs of [Lachmann] would not be considered very first-rate at Eton, and though Hermann’s translation from the Wallenstein [into Greek] might have failed to obtain the Person prize at Cambridge, these Prolusiones are considered wonderful efforts in Germany, and certainly could not be imitated by many of the doctores umbratici who abound there (p. 158).

Scholarly publications are useful in their way. Composition of Greek and Latin verse, however, provides a far better metric for true education. And the production of Greek and Latin verse is designed not to advance human understanding but to satisfy one’s superiors at institutions such as Eton and Cambridge. Education is inherently hierarchical and prepares its recipients to take their place within other hierarchies.

Classical studies could evolve in this way because it provided a widely recognized instrument of social and economic advancement.

The prizes proposed are of enormous value. It is estimated that the first place in either Tripos at Cambridge is worth in present value and contingent advantages about [pounds] 10,000, to say nothing of the effect produced by the prestige of early success on the career of the young barrister and statesman (p. 154).

In 1856, ten thousand pounds was an immense sum—50 years work for surgeons and doctors who, in 1851, earned just over two hundred pounds a year. [47] Wissenschaft aside, classics not only allowed nineteenth century men to pass the civil service exam and run India, but to pursue a number of privileged occupations. Oxford and Cambridge still maintain extensive and very selective programs in Greek and Latin. But a few hundred classicists fortunate enough to gain entry to Oxford and Cambridge or a roughly equal number of students earning degrees in Greek and Latin at American Ivy League schools cannot on their own sustain a field. Programs based within such institutions are problematic models of education, particularly because of the old association of classical studies and problematic forms of privilege. Greek and Latin as an education of the privileged is not a promising model. As noted above, a perception exists that the sciences are superior to the humanities because they allow merit to rise despite ethnic background.

Where classical studies may have vied with mathematics in the nineteenth century, a broader array of experimental sciences and technological fields have replaced classical studies (and even to some extent pure mathematics) as recognized instruments of advancement. And at least some who are not European in descent now view in the laboratory and technological disciplines instruments to rectify the biases of class and race that they see in the humanistic fields of the twenty-first century.

In Donaldson, we see one direct voice that attacks not only Humboldt’s vision of the university but also the values that Humboldt urged upon the student of the past. Humboldt certainly did not yet articulate attitudes on gender and class that would reflect the norms of twenty-first German or British culture, but the call to remove barriers of religion, nation and color was a bold assertion in a process of Enlightenment that would develop (and provoke murderous reaction) over time. Where Humboldt called for the historian to advance a common humanity, Donaldson sees in the best education a feature of the higher classes, a method by which to identify the most vigorous young men to impose British will upon its Indian subjects, and a feature that characterizes British superiority over its emerging German rivals. While some leading professors in the nineteenth century United States received their academic training in Germany, the curricula that emerged in the United States followed in Oxbridge traditions, with institutions such as Harvard and Yale creating college and house systems that built upon the college system at Oxford and Cambridge. This hybrid tradition produced a system where the faculty were increasingly expected to publish and to advance Wissenschaft, but the students remained locked in a culture where they took exams and wrote theses that were similar in function to the Greek and Latin verse compositions that Donaldson so valued.

British Tradition and the twentieth-century Classical Studies in the United States

The hierarchical—and in some measure anti-intellectual——British tradition remained the dominant influence for most demanding classics programs through most of the twentieth century. To some extent this reflected the composition of Ivy-league classics programs, which fed upon students from American boarding schools that were modeled on British public schools and that sought to convert a parent’s wealth into class and status for the child. Although many American classists studied in Germany in the nineteenth century, students from boarding schools such as Andover, Exeter, and Groton, the American counterparts to Eton, Harrow, and Rugby, remained prominent, if not dominant, within American classics departments of the twentieth century.

It is not clear if any North American programs at the undergraduate or MA level in Classics could achieve Humboldt’s ideal of placing the advancement of knowledge as a regular goal for its students. Well into the twentieth century a handful of Classics programs in the United States were able to maintain a program that at least echoed the British model, with an emphasis on imposing upon its students mastery of a challenging subject. Perhaps the strongest programs (supported often by students from expensive boarding schools) built undergraduate degrees around two major components. (MA degrees from these programs were consolation prizes for those who completed coursework but did not go for a PhD.)

First, challenging programs demanded that students cover reading lists of Greek and/or Latin. The reading lists might contain as much as 150,000 words in each language. Students were expected to pass a general examination before graduation on these reading lists. Whether students majored in Greek, Latin, or both languages, all students took the same examination. Those who majored in Greek and Latin had greater choice on what passages they could select in a typical three-hour translation exam on Greek and Latin, splitting their time between the languages. They could, in effect, read 75,000 words of Greek and 75,000 words of Latin. Students of Greek or Latin needed to be familiar with roughly 150,000 words of one language or the other. [48] Put into perspective, the novel Moby Dick contains more than 200,000 words.

Nevertheless, perhaps half of the undergraduates who received degrees from an institution such as Harvard University in the 1980s were well prepared to read their 150,000-word examination corpus of Greek or Latin. Perhaps one in ten had sufficient command of the language to fluently read passages that they had seen before, with vocabulary and grammar primarily from passages that they had studied. Of course, neither a 150,000—nor even less a 75,000-word—reading list, provides a broad enough vocabulary to support general reading. Because advanced classes were taught in English and students spent their time primarily learning about particular Greek or Latin sources rather than learning the individual languages, they could not develop linguistic competence comparable to that of their counterparts in Russian or Chinese.

The reading lists nonetheless constituted a great strength of classics programs. Students could not simply pick less demanding classes or cram for particular courses and then, their A-s and A minus-s assured by memorizing short reading lists, accumulate the grade point average needed for high honors. Each year students with high averages at Harvard would do so poorly on their examinations that they should probably have failed. Usually these students were allowed to pass but the knowledge of that reading list at the end of senior year challenged every student at the least to worry about, if not to take active steps for, the looming examinations. The most ambitious students spent their free time during the school years and summers reading independently or in small groups.

The reading lists were hardly perfect. Reading lists tended to be rigid from year to year—students would spend years preparing and they could not have their previous work rendered irrelevant by a new list. And, of course, everyone had to take the same examinations—it was not practical to consider allowing each student to define a separate reading list. Every student had to read the same texts. If visiting professors covered the wrong plays of Greek tragedy, they could, however eminent they may have been, find themselves with no students at all. Students had to game the system as much as they had to read Greek, but the game was hard enough that success was difficult and demonstrated a capacity to master complex linguistic systems, however inadequately they were taught.

Second, if students wanted high honors, then they needed to do more than take tests and thus had to produce something of their own. One object was to compose an undergraduate thesis, perhaps sixty pages in length, on some relevant topic. In a well-structured program, students would have an opportunity to lay the foundations of such research in their junior years—something much harder to do when students spend a junior year abroad in a separate program. For many, producing a thesis with multiple chapters, comparable to four fifteen page term papers, was a transformative event, allowing them to understand for the first time something of what sustained independent research that was driven by their own interests and completed by working on their own with only occasional guidance from an advisor. Not everyone was suited to this and many who tried a thesis could not finish. But a system was in place to support those who tried.

But the undergraduate thesis in classics was not a contribution to learning nor was it a partnership between an instructor and student both seeking the common goal of advancing Wissenschaft. The thesis was more of a rhetorical exercise that resembled, but did not constitute, a contribution to learning. The most highly rated theses (in at least one case, those ranked magna or summa cum laude) would be consigned to preservation in the archives. Students would present their carefully typed manuscripts in a particular format on 300-year paper to be preserved away from prying eyes in the university archive for generations to come.

Students might avoid a thesis and original thought altogether, taking advanced courses in Greek and/or Latin prose composition, aspiring (with little realistic hope of success) to compete with the achievements of British schoolboys and producing compositions that would trouble no one but their instructors and perhaps a few of their fellow-classmates. In this tradition, original thought was unnecessary for success. Students needed to master complex content and to express themselves according to complex grammatical and rhetorical rules. They did not need to say anything of interest to anyone. They needed only to please those paid to review their work.

At the beginning of the twenty-first century, the program listed above, imperfect as it may have been, was no longer sustainable. In 2009, the Harvard Classics Department, for example, gave up its undergraduate reading lists and general examinations [49] ——as of 2012, Yale University is the only known undergraduate program that still maintains a reading list in Greek and Latin. Students take courses in Greek and Latin and major in language-intensive tracks at institutions such as Harvard, as they can at a number of institutions. They receive grades and can ask for written letters of recommendation but the meaning of the grades and letters is anyone’s guess.

Courses in elementary or advanced Greek and Latin composition still exist. The elementary courses provide some basic active command of generic Greek and Latin prose, helping students acquire a minimal sense of one or the other language as an instrument of communication. Advanced composition courses, where students imitate the style of a particular author, can be extremely useful in helping students develop the ability to appreciate differences of style that passive reading does not communicate. Both courses are comparable to training that students receive in language tracks for classes such as Arabic or German. They do not involve independent intellectual activity to advance the understanding of anyone but the student.

Theses remain as an option in many classics programs. But if even the most challenging classics departments are unable to maintain the examination culture on the mastery of Greek and Latin that Donaldson and other British schoolmasters advocated, they have nevertheless remained true to this amateur tradition. They will not become clumsy “learned writers” and their undergraduate research will trouble no one except their professors and perhaps admissions committees for advanced research. Fortunately, few classics BAs will have to compete with their fellows in the sciences for NSF fellowships that value evidence of independent research.

As the twentieth-century took shape, students could increasingly major in classics without knowledge of Greek or Latin. Dedicated and often volunteer labor by classics faculty has preserved the study of the languages—with 55,000 students enrolled in Greek and Latin in 2009. Students with access to such classes can study the languages as far as they wish and their instructors, in their separate classes, care to push them. Some students of determination and curiosity can still flourish—because, of course, some students are so motivated and disciplined that they can learn almost anything, given time and encouragement.

Some PhD programs that cover Greek and Latin continue to admit students and to grant PhDs—research universities have good reason to support highly ranked departments. Research universities are measured in part by the number of PhDs they produce while research faculty need graduate students if they are to spend time reading and discussing Greek or Latin, much less discussing their own research in their classes.

Challenging undergraduate programs that might intimidate students seem to be unnecessary. MA and post-baccalaureate programs helped make up for the linguistic training that students no longer possessed at graduation. And the relatively small number of new classicists needed to support the field meant that the field did not need well-defined undergraduate programs in Greek and Latin—the inherent interest of Greco-Roman culture drew far more extraordinarily talented students, who could educate themselves in preparation for graduate study than were needed to fill the jobs that members of the field could justify.

Of course, Classics departments that do not advance the research profiles of their universities can find it difficult to replace retiring faculty. Such departments may shrink, take on the status of programs, or be subsumed within other departments. Courses based on English translations about subjects such as Greco-Roman mythology, history, literature, science, and religion can draw large and enthusiastic enrollments and thus justify faculty positions—especially as such classes and their faculty do not require expensive laboratories and are much less costly to support than their equivalents in chemistry, biology or physics.

The real threat may not be to the study of classics but to the kinds of careers for which the next generation of classicists can hope. One commonly expressed fear is that an increasing percentage of classes may be taught by poorly paid, part-time instructors who teach on a course-by-course basis and do not receive health or retirement benefits. This danger is appealing to many humanists because it places university administrations in an unfavorable light.

The rise of the part-time faculty may not be the greatest danger. The next generation of humanist faculty may have long-term positions and enjoy health and retirement benefits. They may, however, be full-time lecturers, paid perhaps half as much as, and teaching 50% more than, tenure-stream faculty. These are full-time teachers who are not paid to conduct research and can devote their time not only to their courses but also to advising and supporting students. If faculty research does not directly contribute to what undergraduates learn and or to the prestige of the institution, why should institutions force parents to pay for more expensive tenure-stream faculty? When lecture classes do not lead to research seminars where students can contribute and develop original research, why shouldn’t faculty be paid to use the current textbooks and research of others?

Twentieth-century classicists have thus created programs that can serve a very wide audience and that can be sustained in some form over long periods of time. But it was much harder for such programs to make compelling cases that they matched either a rigor of training or opportunities to participation in research that characterize newly-formed and rapidly-growing majors in the sciences and engineering. Classics can no longer support the highly-structured and demanding language programs that survived into the twentieth century, while the sciences have moved forward, becoming more demanding and opening up new opportunities for student development.