Deixis [5]

[ ].ρά.α τόδε Λέσβιο⌞ι ...]....εὔ⌞δει⌟λον τέμενο⌞ς μέγα ξῦ⌟νον κά[τε]⌞σσα⌟ν ἐν δὲ βώ⌞μοις 4 ἀθανάτων ⌞μακά⌟ρων ἔθη⌞καν κἀ⌟πωνύ⌞μασσα⌟ν ἀντί⌞αον⌞ Δ⌞ία⌟ σὲ δ' Α⌟ἰολήιαν ⌞[κ]υδα⌟λίμα⌞ν θ⌟έον π⌞ά⌟ντων γενέθλαν, τὸν δὲ ⌞τέρ⌟το⌞ν 8 τόνδε κεμήλιον ⌞ὠ⌟ν⌞ύμα⌟σσ[α]ν Ζόννυσσον ὠμήσ⌞ταν. ἄ[γ⌟ι]τ̣' εὔνοον θῦμον σκέθοντε⌞ς ἀμμετ⌟έρα[ς] ἄρας ἀκούσατ', ἐκ δὲ τῶ⌞ν̣[δ]ε̣ μ̣ό̣⌟χ̣θ̣ων 12 ἀργαλέας τε φύγας ῤ[ύεσθε· τὸν ῎Υρραον δὲ πα[ῖδ]α ⌞πεδελθ⌟έ̣τ̣ω̣ κήνων Ἐ[ρίννυ]ς ὤς πο⌞τ' ἀπώμ⌟νυμεν τόμοντες ἄ..[ ´ .]ν̣.⌞ν̣⌟ 16 μηδάμα μηδ' ἔνα τὼν ἐταίρων ἀλλ' ἢ θάνοντες γᾶν ἐπιέμμενοι κείσεσθ' ὐπ' ἄνδρων οἲ τότ' ἐπικ..ην ἤπειτα κακκτάνοντες αὔτοις 20 δᾶμον ὐπὲξ ἀχέων ῤύεσθαι. κήνων ὀ φύσγων οὐ διελέξατο πρὸς θῦμον ἀλλὰ βραϊδίως πόσιν ἔ]μβαις ἐπ' ὀρκίοισι δάπτει 24 τὰν πόλιν ἄμμι δέ̣δ̣[.]..[.].ί.αις οὐ κὰν νόμον [.]ον̣..[ ]´̣[ ] γλαύκας ἀ[.]..[.]..[ γεγρά.[ 26 Μύρσιλ̣[ο

… a great temenos, far-seen,

established as the common one, and therein altars

of the blessed gods they put

and they named Zeus God of Suppliants

and you (they named) the Aeolian, Glorious Goddess,

Mother of all, and the third,

this one, [27] they named Kemēlios, [28]

Dionysus, Eater of Raw Flesh. Come, with well-disposed

spirit to our prayer

pay heed, and from these toils

and from terrible exile rescue [29] us.

The son of Hyrrhas (i.e., Pittacus) let

the Erinys of those men pursue, as once we swore

cutting …

never not any of our companions

but either dead and clothed in earth

to lie, at the hands of men who at that time …

or else having killed them

to rescue the people from their woes.

Of those men, Pot-Belly took no thought,

as regards their spirit, [30] but casually

having trod upon the oaths he devours

our city …

not according to law …

grey …

written (?) …

Myrsilus … .

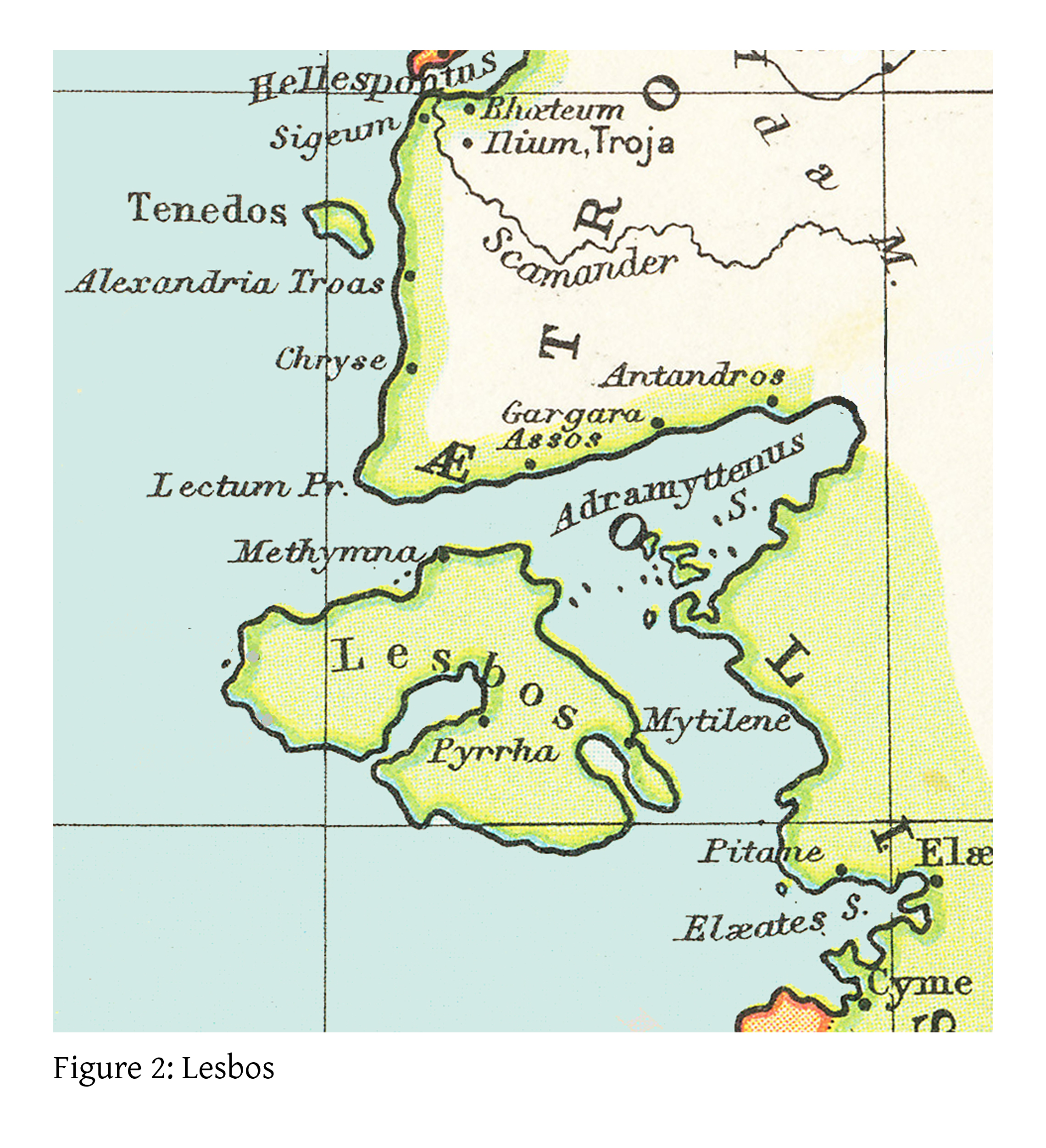

ἀγνοι̣σ̣..σ̣βιότοις..ις ὀ τάλαις ἔγω ζώω μοῖραν ἔχων ἀγροϊωτίκαν ἰμέρρων ἀγόρας ἄκουσαι 4 καρ̣υ̣[ζο]μένας ὦγεσιλαΐδα καὶ β̣[ό]λ̣λ̣ας· τὰ πάτηρ καὶ πάτερος πάτηρ κα..[.].ηρας ἔχοντες πεδὰ τωνδέων τὼν [ἀ]λλαλοκάκων πολίτ̣αν 8 ἔ.[..ἀ]πὺ τούτων ἀπελήλαμαι φεύγων ἐσχατίαισ', ὠς δ' Ὀνυμακλέης ὠ̣θά[ν]ά̣ος ἐοίκησα λυκαιμίαις φεύγων τ⌞ον⌟ [π]ό̣λεμον· στάσιν γὰρ 12 πρὸς κρ.[....].οὐκ ἄμεινον ὀννέλην· .].[...].[..]. μακάρων ἐς τέμ[ε]νος θέων ἐοι̣[.....].ε̣[.]αίνας ἐπίβαις χθόνος χλι.[.].[.].[.]ν̣ συνόδοισί μ' αὔταις 16 οἴκημι κ[ά]κων ἔκτος ἔχων πόδας, ὄππαι Λ[εσβί]αδες κριννόμεναι φύαν πώλεντ' ἐλκεσίπεπλοι, περὶ δὲ βρέμει ἄχω θεσπεσία γυναίκων 20 ἴρα[ς ὀ]λολύγας ἐνιαυσίας

].[´̣].[.].ἀπ̣ὺ πόλλ̣ω̣ν .ότα δὴ θέοι

].[ ´]σ̣κ̣...ν Ὀλ̣ύ̣μ̣πιοι

]......

24 .ν̣α̣[ ]...μ̣εν.

I live with a rustic’s lot,

longing to hear the agora

announced, Agesilaïdas,

and the council. That which my father and father’s father

grew old in possession of amongst these

mutually harming citizens,

from this I am driven away,

an exile in the border-land, and like Onomacles

the Athenian I settled in, “Wolf-Battle,” [49]

fleeing the war. For, as for strife,

against … is it not better to be rid (of it)? [50]

… into a precinct of the blessed gods

I … , having trod on the black earth.

… myself meetings themselves

I dwell keeping my feet out of trouble, [51]

where the Lesbian women, when they are judged for beauty,

go, they of trailing robes, and round about rings

the divinely-sounding peal of women’s

yearly sacred cry.

… from many (troubles) when (will) the gods

(free me?) …

- Ocular deixis. Alcaeus addressed a certain Agesilaïdas who was present at a symposium or on some other occasion at which this poem was first delivered.

- A mixture of ocular deixis with imaginary deixis. Two possibilities:The real Alcaeus addressed an imaginary Agesilaïdas at a symposium or other occasion at which this poem was first delivered. As commentators have observed, Agesilaïdas does not have any role in the rest of the poem. On this interpretation, then, Agesilaïdas was there in the poem only as a way of establishing a particular ethos for the poem, the ethos that presumably was immediately apparent in meter and melody. [53] This poem, as Rösler argued, was an epistle, which was recited before the hetaireia in the absence of Alcaeus and addressed to Agesilaïdas. [54] Under these circumstances, he and the others present had to imagine Alcaeus as the speaker, while the addressee, Agesilaïdas, was visible. [55]

- Completely imaginary deixis. This poem was not necessarily an epistle but a performance piece performed on some occasion or other by someone or other. Alcaeus was imaginary, as said. Agesilaïdas was also imaginary, simply the persona of the comrade, with which any auditor could identify. On this view, the situation evoked here as present could even have been in the past. On this interpretation, the deixis approaches fiction. [56]

- Other. Of course one could continue the list of possibilities. For example, Agesilaïdas as the performer of the poem.

Synkrisis of frs. 129 and 130B

Everyday expressions

᾿Α]ρνήσιος

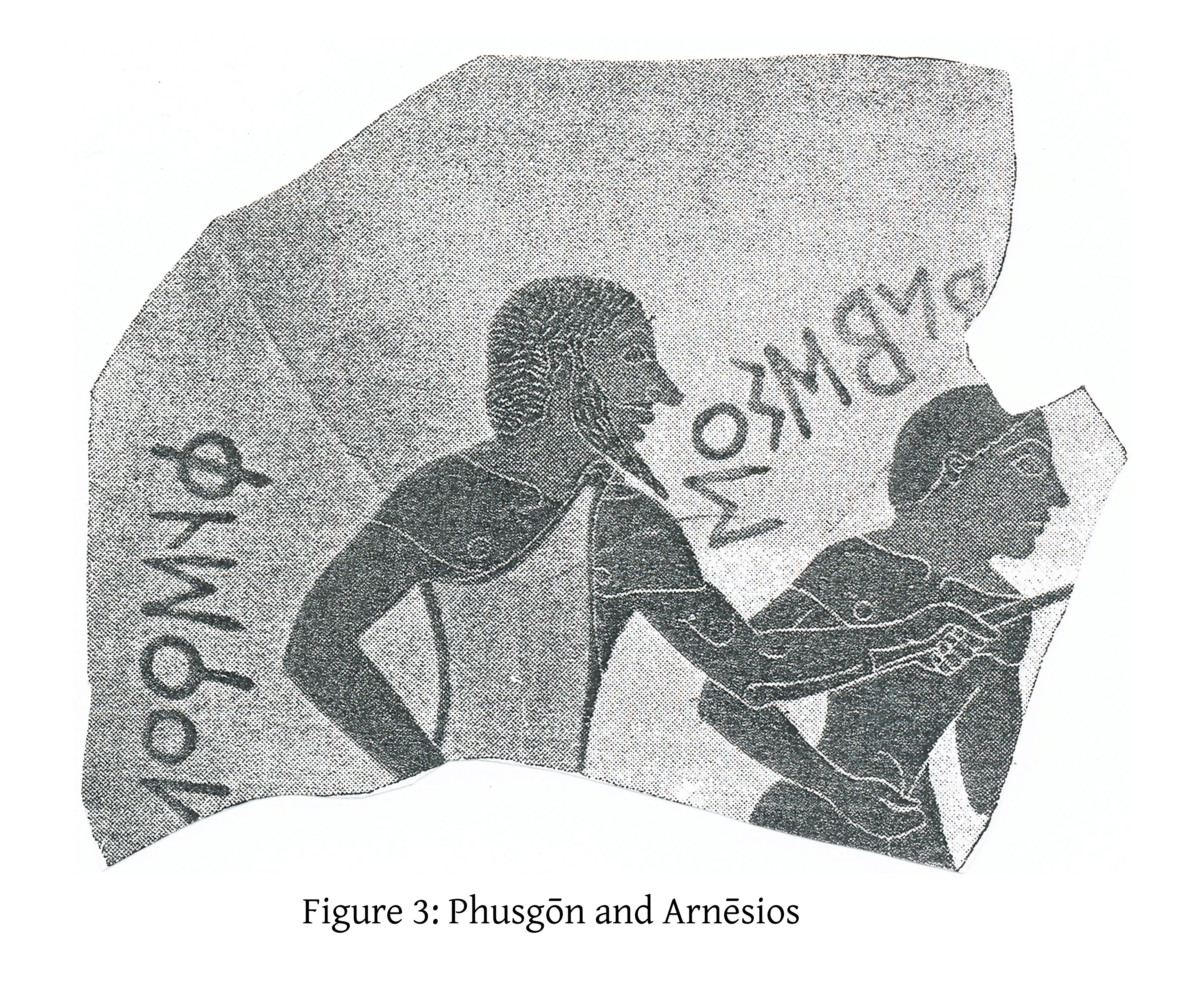

on a Corinthian pinax of the mid-sixth c. B.C.E. This pinax belongs to the group of votives dedicated by members of the pottery industry. [76] The names are probably labels for the two figures, a man and a youth, who appear on the pinax, i.e., the dedicators (Wachter 2001:142, 348). See Figure 3 (from Pernice 1897:30). Notice that, in the drawing, Phusgōn does not have a pot-belly. The appearance of the name on the pinax makes it unlikely that Alcaeus invented the epithet for Pittacus (contrary to Hamm 1957:84, the standard opinion). Unless one wants to argue that this Corinthian potter heard of Alcaeus’ epithet for Pittacus and decided to adopt it, one has to assume either (1) that the potter or one of his comrades independently invented Phusgōn or (2), what seems to me more likely, that it already had a fairly widespread existence. One has to wonder, if the potter adopted the name for himself, how opprobrious it really was. The suffix -ων, to quote Meillet-Vendryes, furnished “nouns designating beings provided with a certain quality” (Meillet and Vendryes 1969:411–12). There is nothing pejorative in the suffix itself. Did the Athenian called “Platōn” feel shame every time he heard his name? “Phusgōn” may be one of those nicknames that can be either affectionate or opprobrious depending on the circumstances. Compare “Jellybelly,” the nickname of a cooper who worked in the cooperage of the Jameson Distillery, Dublin, Ireland (his name appears in a list on a sign in the cooperage). If his fellow-coopers called him “Jellybelly,” how opprobrious was the name? Probably it became less affectionate and more opprobrious if an enemy used it. The stylistic level of the name Phusgōn, in any case, is obviously lower than that of the patronymic “son of Hyrrhas” (13), but not obviously lower than the level of iambic, a kind of style that, as we will see, these poems admit (see on 22–23 and on fr. 130b.7 below). Phusgōn happens to be an item in a list, in Diogenes Laertius 1.81, of seven opprobrious epithets and nicknames used of Pittacus by Alcaeus (fr. 429 = Pittacus Test. 3 Gentili-Prato; cf. Davies 1985:34). These items can be presumed to come from poems of Alcaeus (unless one believes that Diogenes Laertius or his source has access to some biographical tradition independent of the poems). The list is thus strong evidence of the heterogeneity of Alcaeus’ diction and its lack of anything like “decorum.” [77] Cf. Rodríguez Somolinos 1998:242–46, an extensive discussion under the heading “Valoración ética, insultos.”

Reflections on the survey

But the heterogeneity of the language of Sappho and Alcaeus was still more complex. Consider the conclusion of Rodríguez Somolinos:

With the prosaic quality of Alcaeus in particular, one returns to the remark of Dionysius of Halicarnassus about political rhetoric with which the survey of everyday expressions offered here began. What I hope to have begun to show is that the heterogeneity which Rodríguez Somolinos finds in the corpus of Sappho and Alcaeus as a whole can be found, to some extent, in individual poems.

Conclusions

Appendix: Erinyes in archaic Greek verse

Figures