Nancy Sultan

The year 2011 marks the 50th anniversary of the Kennedy Administration and Jacqueline Kennedy Onassis’ tenure as First Lady. [1] Now, Jacqueline, who died in 1994, is in the news again because a new book of her recorded interviews with the historian and Kennedy aide Arthur Schlesinger Jr, Jacqueline Kennedy: Historic Conversations on Life with John F. Kennedy, came out in September. There, Jackie strongly asserts her desire to portray her husband JFK as a person who was passionate about Greek culture and art—a Greek, not a Roman. [2] Although Jackie insisted that she took her ideas from her husband, it is clear that she had her own ambitious agenda for the JFK administration and developed an ingenious way to promote it—through classical allusions. The Classical Ideal permeated practically every aspect of the brief but intense Kennedy Administration, which itself influenced the formation of the American cultural identity in a profound and lasting way. As a tribute to Gregory Nagy, whose passion for cross-cultural and interdisciplinary approaches to Hellenic Cultural Studies inspired my own, I offer this exploration into the Hellenization of the cultural program of the Kennedy Administration.

On January 20, 1961, JFK was sworn in as president. Robert Frost—the first poet in the history of our country to be invited to a presidential inauguration—wrote a poem for the occasion, in which he called the Kennedy presidency “the glory of a next Augustan age…of a power leading from its strength and pride, of young ambition eager to be tried…a golden age of poetry and power.” [3] Later same day, the musical “Camelot” opened in Washington. This coincidence has resulted in a misleading epitaph placed upon the administration by none other than Jackie herself, in an interview with T.H. White, the reporter then writing for Life Magazine shortly after JFK’s assassination. Jack Kennedy, she said, had loved the title song to the musical, for the lyrics represented the way Americans had come to see his time in the White House as something both magical and mythical. [4]

I argue that it was not “Camelot,” but the classical ideals of Periclean Athens that guided the Kennedys, especially Jackie, as she fulfilled her youthful wish to be the “overall art director of the 20th century.” [5] Jackie imagined herself as America’s Greek muse, projecting the message of the simple beauty, youth, and vitality of the Kennedy Administration through visual metaphors drawn from neoclassical themes inspired by Old Master paintings and 18th–19th century literature, art and architecture. Cassini once remarked that while JFK was busy with the presidency, Jackie was creating an American Versailles. [6]

Like Pericles’ administration, Kennedy’s was “distinctly aristocratic, democracy in name, but in practice, government by the first citizen” (Thuc. ii.65; Plut. Vit. Per. 9). Like Pericles, JFK—whose family, many argued, was the closest thing to royalty that we had in America—believed that money was the source of power. Jackie believed this too; her own family background was presented as “strictly Old Guard” with connections to the White House (her great-grandfather, M. Bouvier, was a cabinetmaker who made furniture for JQ Adams). [7] The Kennedy inner circle of advisors and confidants had pedigrees, and whenever possible, “old money.” Jackie’s designer, Cassini, was a Russian Count. Like Pericles’ administration, JFK’s was the subject of scandals, brushes with the law, and personal tragedies.

The Kennedy building program echoes that of Pericles’ in the construction (and, in the case of the White House and Lafayette Square, restoration) of public buildings that, as Plutarch described, “seemed venerable the moment they were born, and at the same time, possessed a youthful vigor which made them appear to this day as if they were newly built…” (Plut. Vit. Per. 11). The cultural programs of both administrations “gave the [citizens] greatest pleasure, adorned their city, and created testimony that the tales of their ancient power and glory were not mere fables” (Plut. Vit. Per. 12).

Pericles, says Plutarch, pursued cultural distinction not only with his building program on the Acropolis, but also by ordering the building of the Odeon and establishing a musical contest to be held there as part of the Panathenaia (Plut. Vit. Per. 13). Like Pericles, Kennedy understood the nation’s aesthetic style to be integral to its political initiatives, and he believed that government should lead the way in aesthetically upgrading the country. In an essay contribution to the volume Creative America, designed to raise money for the National Cultural Center in D.C. (the future John F. Kennedy Center for the Performing Arts), the president wrote: “Our city [Washington] inevitably becomes to a degree a showcase of our culture…A free government is the reflection of a people’s will and desire—and ultimately of their taste. It is also, at its best, a leading force, an example, and a teacher. I would like to see the works of government represent the best our artists, designers, and builders can achieve.” [8]

Kennedy himself saw an inspirational role model in Pericles; he endeavored to achieve for America what Pericles had achieved for Athens. He included the name and words of Pericles in many of his speeches on art, culture, and education in America. He was especially fond of Pericles’ Funeral Oration, as quoted by Thucydides. While still a senator, JFK spoke at a convocation of the United Negro College Fund, saying: “Pericles told ancient Athens that it should be the school of all Greece. America today can be the school of all the world. But American educators must act with the necessary vision.” [9] As president-elect, Kennedy addressed the Joint Convention of the General Court of the Commonwealth of Massachusetts with: “For what Pericles said of the Athenians has long been true of this commonwealth: ‘we do not imitate—for we are a model to others’.” [10] During the presidential campaign, when asked his view on music in relation to the federal government and domestic world affairs, Kennedy replied, “There is a connection, hard to explain logically but easy to feel, between achievement in public life and progress in the arts. The age of Pericles was also the age of Phidias.” [11]

It was Jackie who, quietly at first, and then dramatically and at huge expense, directed, orchestrated, and stage-managed JFK’s new program of cultural development. She had always planned to make Washington the social and intellectual center of the country. When Kennedy was a senator, she urged him to push a bill to preserve the neoclassic buildings in Lafayette Square—the Belasco Theatre, the Dolly Madison and Benjamin Taylor houses—all of which were scheduled to be razed by the Eisenhower administration. [12] She, too, saw her husband as a Periclean statesman, not a politician; [13] with the mantra that “everything in the White House should be the best,” [14] she surrounded the president with finest craftsmen, artisans, musicians, intellectuals.

Jackie’s cultural interests were deeper and wider than her husband’s; at Miss Porter’s School she fell in love with the classics and the neoclassical art and architecture of the Directoire and Empire Periods; both a Francophile and an Anglophile, her favorite authors included Baudelaire, Oscar Wilde and Tennyson. [15] Her influence on Jack’s understanding and appreciation of the classics is noticeable; He was already a reader of ancient history, but after he married Jackie he began regularly to reference classical authors and Greco-Roman ideology in his speeches, whether he was addressing students, the public, or congress. In a progress report on physical fitness, for example, Kennedy quoted Pindar and urged America to follow the example of Greece and Rome in exercising both the body and the mind. [16]

The similarities between JFK’s inaugural speech and Pericles’ Funeral Oration are striking. Both begin with the deeds of the ancestors who brought their country to its present glory, and both speeches celebrate the commitment of the present generation to carry that work further. Both speeches contain praise of and pledges to the allies, and warnings to enemies.

Yet, Pericles praises the Athenians for their delight in beauty and good taste, while JFK—in remarks on several different occasions—criticizes America’s lack of culture and appreciation for the arts: “it is little wonder,” he said in one memorandum, “that we are thought to be one of the great undeveloped regions culturally. At home not only are our prophets without honor; so are our artists, scholars, and intellectuals.” [17] He “looked forward to an America that will not be afraid of grace and beauty.” [18] Kennedy’s plan was to transform the cultural wasteland of Washington and—by extension—America, into an Athens in the age of Pericles.

One month after the inauguration, Jackie announced the formation of a twelve-member Fine Arts Committee to oversee restoration of the White House. By September the same year, congress approved a law making the White House a national monument. [19] She educated her husband in 18th and 19th century art (she had determined that the 18th century was the proper period for the White House), and exactly one year after JFK’s tenure began, Jackie gave the first-ever televised “Tour of the White House.” As she led an estimated 56 million viewers room by room, with CBS correspondent Charles Collingswood as her escort, the neoclassical roots of the American history emerged in architectural motifs, furniture, and artifacts purchased by former White House Presidents Monroe, Chester Arthur, and Van Buren (see fig.1).

Figure 1: The Minerva Clock, purchased in 1818 by Monroe, restored to the mantel of the Blue Room fireplace. Image courtesy of the John F. Kennedy Museum White House Historical Association.

But viewers were not as captivated by the historic relics as they were by Jackie herself, who put the class in “classical” with her youth, unassuming charm, and grace. For the first time she revealed her sense of theatre and her understanding of the symbolic connections between form and function in her dress and mannerisms.

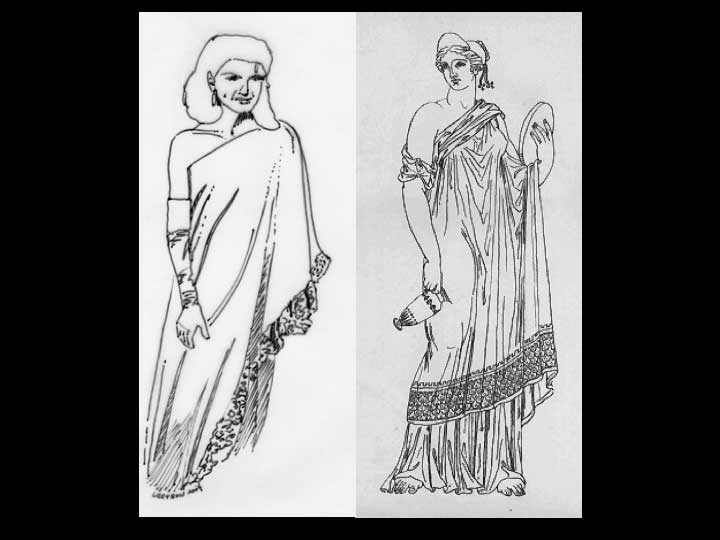

Oleg Cassini wrote that in 1961 American fashion was nowhere. European—especially French—haute couture, which had been embracing classicized forms since the 1790s, held a monopoly that Cassini (despite being born in Paris and educated in Italy) wished to break. Cassini called Jackie a “geometrical goddess,” with “classic features—long neck, sphinxlike eyes, slim torso, broad shoulders, narrow hips and regal bearing—the perfect form for his “new” American-International architectural style, which he called “A-line” [20] (see fig. 2). These clothes not only made the woman, but the woman made the clothes. Jackie designed many of her own outfits and knew how to wear the clothes, how to stand, how to move in the clothes so that her classical sources shined through.

Figure 2: left – Peplos Kore. 530 BCE. Acropolis Museum, Athens. Image courtesy of the University of Texas at Austin webpage: http://ccwf.cc.utexas.edu/~bruceh/cc307/archaic/images/061.jpg; right – Jacqueline Kennedy in her inaugural gala gown made of ivory silk satin twill. Illustration courtesy of Larry Leetzow. © Larry Leetzow, 2011.

The A-line was very much a revival of the 18th-19th century neoclassical (see fig. 3); though Cassini frequently made reference to Egyptian fashion and the Nefertiti-style, the clothing that he, Valentino, and Halston designed for Jackie were clearly not pharonic, but rather inspired by the archaic, classical or ptolemaic, merged with eastern iconography [21] (see fig. 4).

Figure 3: left – 1808 Portrait of Madame Charles-Maurice de Tallyrand-Périgord, by François-Pascal-Simon Gérard (1770-1837). Credit: Wrightsman Fund, 2002. © 2000-2008 The Metropolitan Museum of Art. (Koda 2003:93); right – Jacqueline Kennedy in Cassini designed strapless evening dress in pink silk chiffon, 1963. Image courtesy of Corbis Research. © Corbis Research, Inc.

Figure 4: left – Jackie wearing a one-shouldered gown designed by Valentino, worn on an official 1967 trip to Cambodia. Illustration courtesy of Larry Leetzow. © Larry Leetzow, 2009; right – Figure with chiton and himation. Smith, J. Moyr. 1882. Ancient Greek Female Costume. London: Sampson Low, Marston, Searle, and Rivington. 37. Image courtesy of University of Kentucky webpage: http://www.uky.edu/AS/Classics/agfc-moyrsmith.html.

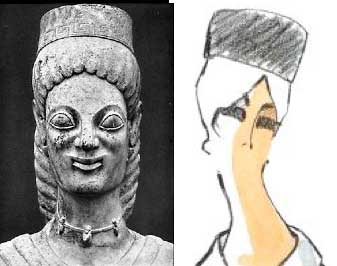

Jay Mulvaney, author of The Clothes of Camelot, explained that “Jackie approached the task of wardrobe creation with a serious discipline—it was a public image that she would forge, an image that would be the distaff counterpoint to the words and actions of her husband.” [22] Let us begin with what Jackie wore to the inauguration: A Cassini designed straight wool coat of a neutral greige color and pillbox hat created by Halston that would become iconic. The hat, a simple (if you will) pincushion shaped echinus, tops off her columnar ensemble that complements the architecture of the west facade of the neoclassical Capitol building, which rose behind the podium. In it’s simplicity, the pillbox hat is at once a Doric Order element representing the same architectonic control and restraint we see in Archaic Greek sculpture—a crown suitable for an Archaic Greek kore or a First Lady (see fig. 5).

Figure 5: left – Berlin Kore, from Keratea, Attica. c. 570-560 BCE. Marble. Staatliche Museen, Berlin. Credit: Art Resource. © Bildarchiv PreuBischer Kulturbesitz.; right – Drawing of Cassini designed white coat dress and pillbox hat. Image courtesy of Oleg Cassini, Inc.

With classical allusions in visual imagery here and throughout her tenure as First Lady, Jackie intended to bring the cultural and artistic elegance of old Europe to the US and further JFK’s own Periclean vision of an America that was the education of the world. She preferred stiff shiny fabrics, the structured minimalism and precisely tailored “covered-up” look of drapery, [23] but for one of the most important public events hosted by the White House, Jackie chose a Cassini designed Greek peplos (see fig. 6).

Figure 6: Oleg Cassini’s drawing of Jackie’s “Grecian-style greenish-gray mossy colored gown in soft jersey,” worn at the White House dinner honoring Nobel prizewinners of the Western Hemisphere, 1962. Image courtesy of Oleg Cassini, Inc.

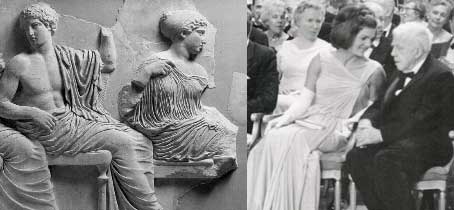

In April of 1962 Jackie hosted, along with the president, the first ever White House dinner honoring forty-nine Nobel prize winners of the Western Hemisphere. For the occasion she had suggested to Cassini that she be draped à l’antique—a sea-green jersey fabric that he described as a “liquid columnar dress suggestive of ancient statuary.” [24] Her hair was prepared in wig-like fashion; the whole ensemble and the way she carried herself revealed her sense of the theatric power of classical sculpture (see fig. 7). Seated in the front row with the President during that evening’s performance by Pablo Casals, Jackie’s innate sense of classical style can be seen in her posture, as she leans over to talk to Robert Frost: in the style of classical relief sculpture, her torso remains facing forward while she turns her head to the left (see Fig. 8).

Figure 7: left – Jackie wearing the peplos-like gown designed by Oleg Cassini. John F. Kennedy Presidential Library and Museum webpage: http://www.jfklibrary.org/Historical+Resources/JFK+in+History/Jacqueline+Kennedy+in+the+White+House+Page+2.htm; right – A caryatid from the north porch of the Erechtheion, Acropolis, Athens, 420-410 BCE. Acropolis Museum, Athens. Image courtesy of the American School of Classical Studies at Athens. © Alison Frantz.

Figure 8: left – Apollo and Artemis on the East Frieze of the Parthenon. Image courtesy of the American School of Classical Studies at Athens. © Alison Frantz; right – Jackie in her peplos, speaking to the poet Robert Frost at the White House dinner honoring Nobel prizewinners of the Western Hemisphere, 1962. Image courtesy John F. Kennedy Presidential Library and Museum webpage:http://www.jfklibrary.org/Asset+Tree/Asset+Viewers/Image+Asset+Viewer.htm?guid={FB9E813D-C577-4920-83EC-564D98F9AB29}&type=Image.

For art historian David Lubin, author of Shooting Kennedy: JFK and the Culture of Images, Jackie was the embodiment of cool, self-effacing, and self-restraining neoclassicism. She was “the conservative force, favoring balance, restraint, the rule of tradition and the privileging of an aristocratic elite.” [25] In an age when celebrities and the powerful worked more closely with the press (or, let us say that the press was more accommodating and willing to suppress and conceal sensitive issues, such as JFK’s sexual indiscretions or Jackie’s smoking), photographers often consulted with Jackie and allowed her a large degree of artistic control over the published images of herself and her husband so that their message remained consistent.

One of the most striking examples of a collaboration between photographer and subject to create a vision can be seen in the portrait of Jackie and her daughter Caroline created by Jacques Lowe in a 1958 photo session at the White House. Hamish Bowles, European editor at large of Vogue and curator of the traveling fashion exhibit Jacqueline Kennedy: The White House Years, organized in 2001 by the Metropolitan Museum and the JFK Presidential Library, wrote that the red fuchsia silk dress worn by Jackie in the famous photograph “exaggerates the principle of the overblouse dress and unfitted line that Jackie endorsed, creating a dress with a structure all its own that becomes a carapace standing away from the figure.” [26] Most impressive is the composition of the portrait, noteworthy for its resemblance to the 4th century BCE Kephisodotos sculpture of Eirene and Plutos, originally commissioned in bronze by the Athenians around 370 BCE to celebrate the inauguration of a Cult of Peace in Athens (see Fig. 9). Note the intimacy created by the eye contact between mother and child, the right arm of the child reaching up to the mother. Both images are the same symbolic expression. If the allegory of the Kephisodotos pair expresses the idea that “peace brings forth and nurtures the growth of wealth,” [27] then might we say the same about beautiful Jackie and Caroline, the cherub with the I Can Fly book in her hand?

Figure 9: left – Jackie in a fuschia silk ruffled shantung designed by Givenchy, with her daughter Caroline, 1959. Credit: Jacques Lowe. © Jacques Lowe Photography; right – Sculpture of “Eirene and Ploutos” (Roman copy of an original of c. 370 BCE.) Staatliche Antikensammlungen, Munich. Credit: Image courtesy of Lahanis webpage: http://www.mlahanas.de/Greeks/Arts/Classic2.htm.

JFK’s assassination in Dallas on November 21, 1963 turned a human whom many around the world already worshipped into a true cult hero. Like Andromache mourning Hector, or Aspasia mourning Pericles, Jackie’s lamentation was a private pain made public (see Fig. 10). Jackie facilitated Jack Kennedy’s transition from hubristic mortal to cult figure, “rescuing him,” as she put it, “from all the bitter people who were going to write about him in history.” [28] Immediately after Jack’s murder, she refused to remove her bloody clothes, crying “let them see what they’ve done.” [29] Jackie was the khoregos of this Greek tragedy.

Figure 10: left – Copy of bronze head said to be Aspasia, Mistress of Pericles, c. 460 BCE.

Paris, Louvre Museum. Credit: Photograph Barbara McManus. Image courtesy Barbara McManus webpage: http://www.cnr.edu/home/bmcmanus/aspasia.jpg; right – Jackie at the funeral of John F. Kennedy. Image courtesy of geocities.com webpage: http://www.kennedy-web.com/jfkfuner.jpg.

It was a public funeral she directed for JFK, with her by his side as poluponos—the vessel of pain, the bloodied witness, a Penelope refusing to hide her grief. At the procession Jackie insisted, against custom, on walking behind the coffin, creating a security nightmare. [30] But she was intent on fulfilling her role as the veiled widow of her hero warrior.

Plutarch wrote that Pericles deserves admiration not only for “the sense of justice and serene temper he preserved amid the many crises and personal hatreds that surrounded him,” but because he was possessed of a “character so gracious and a life so pure and uncorrupt in the exercise of sovereign power that he might well be called Olympian” (Plut. Vit. Per. 39). The same was said of JFK by T. H. White, who wrote that Jackie’s characterization of the administration as ‘Camelot’ was a “misreading of history…Camelot never existed; for it was instead a time when reason brought to bear on public issues, and the Kennedy people were more often right than wrong, and astonishingly incorruptible.” [31]

In his remarks at Amherst College one month before his assassination, JFK said “I look forward to an America which commands respect throughout the world not only for its strength but for its civilization as well.” [32] He had wanted to make Washington “the showcase of our culture,” [33] despite the expense; he referred more than once to Lincoln’s insistence that in spite of the cost, the new Capitol dome, with its bronze goddess of liberty set upon the top, was an inspiration to the Union during wartime. [34] So it was with Jackie, who spent a scandalous $50,000 on clothes, [35] but “after she left the White House, Women’s Wear Daily reported that she probably did more to uplift taste levels in the US than any woman in the history of our country.” [36] She was a revolutionary in the strictest definition of the word, turning again to our classical foundations. In this way, Jackie herself “paved the way for the free and unconfined search for new ways of expressing the experience of the present and the vision of the future.” [37]

Works Cited

Bowles, Hamish. 2001. Jacqueline Kennedy: The White House Years. Selections from the John F. Kennedy Library and Museum. Metropolitan Museum of Art. NY: Little, Brown & Co.

Cassini, Oleg. 1995. A Thousand Days of Magic: Dressing Jacqueline Kennedy for the White House. New York: Rizzoli.

Cater, Douglass. 1961. “The Kennedy Look in the Arts.” Horizon. Sept. 4-17.

Frost, Robert Lee. 1961. “Dedication.” Personal Papers of John F. Kennedy. John F. Kennedy Presidential Library and Museum. January 20. http://www.jfklibrary.org/Asset+Tree/Archives/Documents/JFK+Papers/Personal+Papers/001_Frost+Poem.htm

Kennedy, Caroline and Michael Beschloss. 2011. Jacqueline Kennedy: Historic Conversations on Life with John F. Kennedy. New York: Hyperion.

Kennedy, John F. 1959. Remarks at the Convocation of the United Negro College Fund, Indianapolis, Indiana, April 12. John F. Kennedy Presidential Library and Museum. http://www.jfklibrary.org/Historical+Resources/Archives/Reference+Desk/Speeches/JFK/JFK+Pre-Pres/189POWERS09JFKPOWEES_59APR12.htm

—. 1960. Response to letter sent by Miss Theodate Johnson, Publisher of Musical America, to the two presidential candidates requesting their views on music in relation to the Federal Government and domestic world affairs. Sept. 13. John F. Kennedy Presidential Library and Museum. http://www.jfklibrary.org/Historical+Resources/Archives/Reference+Desk/Quotations+of+John+F+Kennedy.htm

—. 1961. Address of President-Elect John F. Kennedy Delivered to a Joint Convention of the General Court of the Commonwealth of Massachusetts. The State House, Boston. Jan. 1. John F. Kennedy Presidential Library and Museum. http://www.jfklibrary.org/Historical+Resources/Archives/Reference+Desk/Speeches/JFK/

—.1962. “Arts in America: Excerpt from Creative America.” Look Magazine 18 Dec. 105-109.

—. 1963a. Progress Report by the President on Physical Fitness. The American Presidency Project #325. August 13th. http://www.presidency.ucsb.edu/ws/index.php?pid=9371

—. 1963b. Remarks at Amherst College. Amherst, Massachusetts,

October 26. John F. Kennedy Presidential Library and Museum. http://www.jfklibrary.org/Historical+Resources/Archives/Reference+Desk/Speeches/JFK/003POF03Amherst10261963.htm

Klemesrud, Judy. 1968. “Quest of Beauty Dominates Mrs. Kennedy’s Life.” The New York Times. Oct. 18.

Koda, Harold. 2003. Goddess: The Classical Mode. New Haven: Yale U. Press.

Lubin, D.M. 2003. Shooting Kennedy: JFK and the Culture of Images. U. Cal. Press.

Mailer, Norman. 1962. “An Evening with Jackie Kennedy: Being an Essay in Three Acts.” Esquire Magazine. July. 55-61.

Mason. Jerry, ed. 1962. Creative America. Published for the National Cultural Center. NY: Ridge Press.

McFadden, Robert D. 1994. “Death of a First Lady: Jacqueline Kennedy Onassis Dies of Cancer at 64.” New York Times 20 May. http://query.nytimes.com/gst/fullpage.html?res=9401E3DC1238F933A15756C0A962958260

Mulvaney, Jay. 2001. Jackie: The Clothes of Camelot. New York: St. Martin’s Press.

Neils, Jennifer. 2001. The Parthenon Frieze. Cambridge: Cambridge U. Press.

Onions, John. 1979. Art and Thought in the Hellenistic Age. NY: Thames & Hudson.

Pedley, John G. 2007. Greek Art and Archaeology, Fourth Edition. NJ: Pearson.

Wolff, Perry. 1962. A Tour of the White House with Mrs John F. Kennedy. NY: Doubleday & Co.

Footnotes

[ back ] 1. This paper was first published in The Classical Bulletin 84.2 (2008) 49-63.

[ back ] 2. Kennedy 2011:32n50, 145.

[ back ] 3. Frost, Robert. “Dedication.” 20 January 1961.

[ back ] 4. See the Arlington National Cemetery website: http://www.arlingtoncemetery.net/jbk.htm and McFadden 1994.

[ back ] 5. See Mulvaney 2000:xi.

[ back ] 6. Cassini 1995:20, 31. Her clothes would send the message of an “American Versailles,” Cassini remarked. Jackie would be “the most elegant woman in the world” a challenge to the existing “Three Graces: Countess Marguerite Cassini, Alice Roosevelt, and Cissy Patterson.”

[ back ] 7. Cassini 1995:11.

[ back ] 8. Mason 1962:6. See also Kennedy 1962:105-109.

[ back ] 9. Indianapolis, April 12, 1959.

[ back ] 10. Massachusetts State House, Boston. January 1, 1961.

[ back ] 11. Response to a letter sent by Miss Theodate Johnson, Publisher of Musical America, September 13, 1960.

[ back ] 12. Bowles 2001:10-11.

[ back ] 13. Lubin 2003:97. “Jackie compared Jack’s inaugural address to the Funeral Oration of Pericles.”

[ back ] 14. Mailer 1962:57. “Mr. Collingswood said to Mrs. Kennedy “This Administration has shown a particular affinity for artists, musicians, writers, poets. Is this because you and your husband just feel that way or do you think that there’s a relationship between the Government and the arts? ‘That’s so complicated,’ answered Mrs. Kennedy, with good sense. ‘I don’t know. I just think that everything in the White House should be the best’.”

[ back ] 15. See Bradford 2000:28-29, 40-47, 310.

[ back ] 16. Kennedy 1963a. “The Greeks knew it was necessary to have not only a free and inquiring mind, but a strong and active body to develop ‘glorious-limbed youth’, as Pindar, the athlete’s poet, wrote.” Kennedy devoted 168 words to the Greeks and the Olympic Games.

[ back ] 17. Cater 1961:14.

[ back ] 18. Kennedy 1963b. Remarks made at Amherst College during the Dedication of the Robert Frost Library.

[ back ] 19. “The Kennedy Center” webpage: http://www.kennedy-center.org/about/history.html.

[ back ] 20. Cassini 1995:15, 22.

[ back ] 21. See Koda 2003:18-19, in which he compares Jackie in her various classically inspired costumes to a “Gandharan sculpture” and “Botticelli’s Venus.”

[ back ] 22. Mulvaney 2001:3.

[ back ] 23. Mulvaney 2001:31.

[ back ] 24. Bowles 2001:94.

[ back ] 25. Lubin 2003:272, 285.

[ back ] 26. Bowles 2001:43.

[ back ] 27. Onions 1979:98.

[ back ] 28. McFadden 1994. Also available at the Arlington National Cemetery webpage: http://www.arlingoncemetery.net/jbk.htm.

[ back ] 29. Bradford 2000:274. Jackie also “vetoed a secret arrival with Jack’s body carried off the plane out of sight of the press and television cameras for the same reason.”

[ back ] 30. Bradford 2000:279. The tradition was that men walk and women ride in cars behind them. Because of the number of assassination threats, advisors had warned against anyone walking. When Jackie decided to walk, even new President Lyndon Johnson refused to ride for security reasons. “If the widow was going to head the march, no one was going to back out.”

[ back ] 31. McFadden 1994.

[ back ] 32. Kennedy 1963b.

[ back ] 33. Mason 1962:7.

[ back ] 34. Kennedy 1962:105.

[ back ] 35. Klemesrud 1968:32.

[ back ] 36. Mulvaney 2001:31.

[ back ] 37. Kennedy 1962:109. In his essay on art for the Cultural Center fundraising book Creative America, JFK said: “Art means more than the resuscitation of the past: it means the free and unconfined search for new ways of expressing the experience of the present and the vision of the future.”