Modern classical scholarship has only recently begun to examine the subject of animals in antiquity (along with research on women, “barbarians,” slaves, disabled people, and other “marginal” groups). This in spite of the fact that animals abound in ancient art and literature. In ancient Egypt, animals were worshiped as deities. In ancient Greece, they were the companions or theomorphic stand-ins for gods and goddesses. Ancient authors from Plato, Aristotle, Plutarch, Aelian to Porphyry, wrote about animals in works on ethics, morals, and natural history. Prose and poetry writers, including Homer, “Aesop,” Herodotus, Lucretius, Oppian, Ovid, Diodorus Siculus, and Dio Cassius, used animals to tell stories and to illustrate the human experience. Animals were depicted in art from Bronze Age frescoes to Hellenistic coins and pottery.

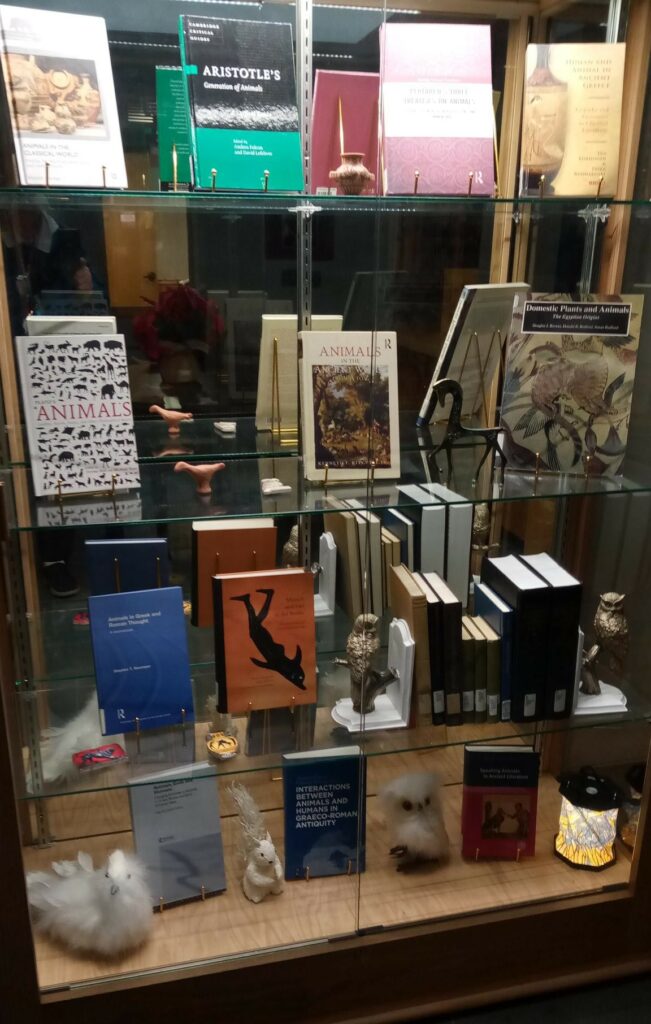

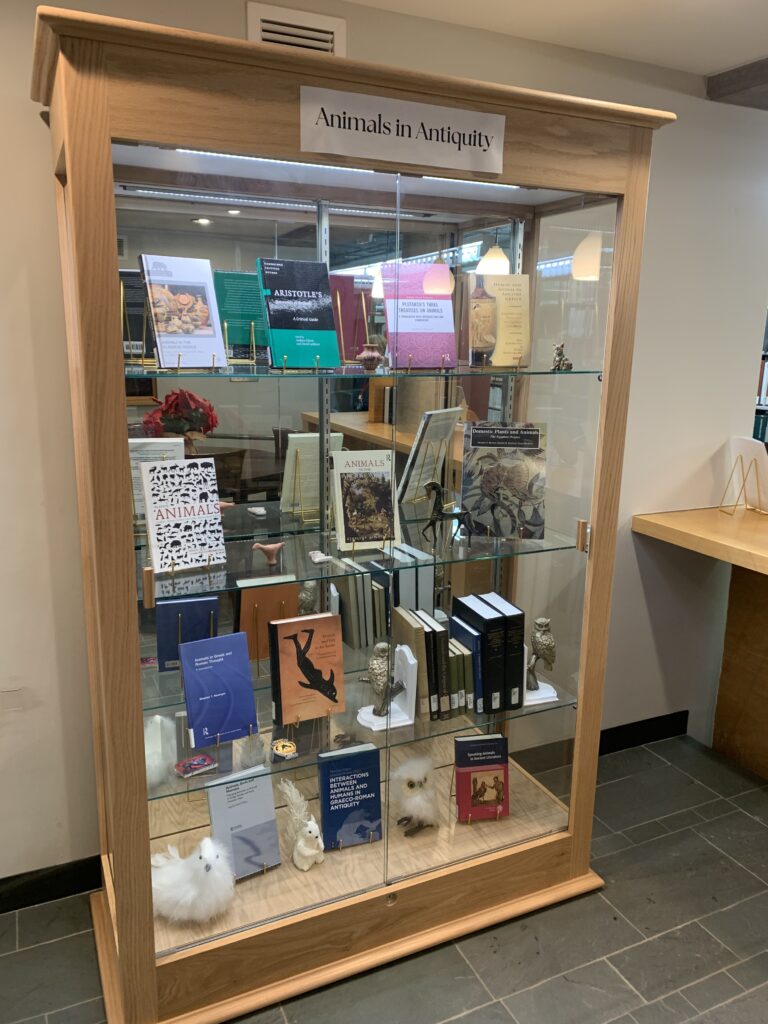

A new exhibition in the CHS library features a select number of modern books on the subject and a visual presentation exhibits a representative collection of ancient literary and archaeological sources about nonhuman animals, at least as humans imagined them, i.e., as artistic and iconographic representations, as pets, as food, as sacrificial tools, as courtship gifts, as objects for displays of manhood, as entertainment, as allegories, and as decoration in medieval book manuscripts.

As challenging as life was for animals in antiquity, it pales by comparison to the 90 billion animals slaughtered each year in modern factory farms, the 100 million animals killed in present-day laboratories and the more than 2 trillion fish killed annually, and the many millions of mammals and birds killed through hunting and trapping. Today, so called livestock (for human consumption) constitutes 60% of the world’s animal population on land, humans 36%, wild animals 4%. The loss of biodiversity within the last few decades is threatening all life on planet Earth. Since the human population was much smaller in ancient Greece and elsewhere, meat consumption, hunting, fishing, and habitat loss were on a much smaller scale than today, and other threats to animal life such as man-made climate change, pesticides, herbicides, power lines, etc., were nonexistent.

However, already in antiquity there were those who objected to the ill treatment of other animals, especially for food consumption. The Roman author Ovid (43 BCE–17/18 CE) in his Metamorphoses has Greek mathematician and philosopher Pythagoras (ca. 570–495 BCE) decry the eating of animal flesh,

“The earth, prodigal of her wealth, supplies you her kindly sustenance and offers you food without bloodshed and slaughter” (15.81-82, Frank J. Miller (LCL) transl.);

Greek Neo-Platonic philosopher Porphyry (ca. 234-305 CE) advocated for shunning animal products altogether,

“If…someone should…think it is unjust to destroy brutes, such a one should neither use milk, nor wool, nor sheep, nor honey. For, as you injure a man by taking from him his garments, thus, also, you injure a sheep by shearing it. For the wool which you take from it is its vestment. Milk, likewise, was not produced for you, but for the young of the animal that has it. The bee also collects honey as food for itself; which you, by taking away, administer for your own pleasure” (On Abstinence 1.21, Select Works of Porphyry, London 1823, Thomas Taylor transl.);

The most passionate plea for the cessation of the eating of fellow animals, though, comes from Greek philosopher, essayist, and biographer Plutarch (46-120 CE) in his dialogue “On the Eating of Flesh” in Moralia in which he writes,

“Can you really ask what reason Pythagoras had for abstaining from flesh? For my part I rather wonder both by what accident and in what state of soul or mind the first man who did so, touched his mouth to gore and brought his lips to the flesh of a dead creature, he who set forth tables of dead, stale bodies and ventured to call food and nourishment the parts that had a little before bellowed and cried, moved and lived. How could his eyes endure the slaughter when throats were slit and hides flayed and limbs torn from limb? How could his nose endure the stench?” (993a-b, Harold Cherniss and William C. Helmbold (LCL) transl.);

“…it is absurd for them to say that the practice of flesh-eating is based on Nature. For that man is not naturally carnivorous is, in the first place, obvious from the structure of his body. A man’s frame is in no way similar to those creatures that were made for flesh-eating: he has no hooked beak or sharp nails or jagged teeth, no strong stomach or warmth of vital fluids able to digest and assimilate a heavy diet of flesh. It is from this very fact, the evenness of our teeth, the smallness of our mouths, the softness of our tongues, our possession of vital fluids too inert to digest meat that Nature disavows our eating of flesh” (994f-995a);

“…Even when it is lifeless and dead, however, no one eats the flesh just as it is; men boil it and roast it, altering it by fire and drugs, recasting and diverting and smothering with countless condiments the taste of gore so that the palate may be deceived and accept what is foreign to it” (995b);

“…for the sake of a little flesh we deprive them of sun, of light, of the duration of life to which they are entitled by birth and being. Then we go on to assume that when they utter cries and squeaks their speech is inarticulate, that they do not, begging for mercy, entreating, seeking justice…” (994e).

Classical antiquity is a never-ending source of wisdom and inspiration. For more source texts and images, see this web page accompanying the physical book exhibit.

To learn about CHS events open to the public or to apply for CHS library access for scholars researching ancient Greece, consult the CHS website and social media posts.