Where are you now? Mingled with the dust?

When my eyes were fixed on the road I said

“Perhaps I will learn news of my child and Rostam.”

My gomān [“fancy” or “suspicion”] was thus, and I said, “now you are wandering around the world,

searching continuously, and now, having found your father,

you hasten to return.”’

Tahmina both denies and accepts the death of her son. This ambiguity between angry denial and abject resignation corresponds to an ambiguous self-characterization. She speaks with the voice of a woman of all ages of life, be it a young bride who has just become the mother of a first-born or be it a bitter old widow who has known all along the cruelty of a world where men are fated to wage war. The universalized image of a grieving woman enhances the rhetoric of “the public view of personal disaster.”

that Rostam would pierce your liver with a dagger?

She now gets straight to the point, mincing no words. This is not only the last thing she expected, but she sees no reason why she should have expected it in the first place. The abrupt switch — from her almost disbelieving that Sohrāb is really dead and her not even mentioning his father’s hand in the son’s death to her furious and irrefutable statement of fact — is cloaked in a rhetorical question that speaks in the voice not only of any woman of any age but of any man. What man, in his right mind, would deliberately kill his own child? Surely such a man is not human.

When he saw your face, your tall stature and hair?

Had he no pity upon your middle [gerdgāh] — that very thing which Rostam lacerated with his sword?

As Tahmina continues to express her misery at this outrage, she plays up the difference between her humanity and Rostam’s lack of it by pointing out how the father failed to recognize in his son what she as a mother knew so intimately. Tahmina expresses such pride — as she describes her son, whom she reared into early manhood, with the intimate detail of his hair, something that would not be seen by all, especially in battle, since Sohrāb would then be wearing a helmet. By mentioning his hair and then moving on to his gerdgāh, which not only means ‘middle’ but also ‘navel,’ she emphasizes her own attachment to Sohrāb, because only she as a mother, and she alone, was once physically connected to Sohrāb, as she nourished him in utero. There is a striking parallel in Kurdish women’s laments, where the interjection rō / rū is used frequently in the sense of ‘alas!’: this interjection is actually derived from the word rūd or rūda, meaning ‘umbilical cord’ (Mokri pp. 465–466). Her lament now turns to the audience, asking them how they could expect such a savage as Rostam to act otherwise. Rostam had only seen Sohrāb once in his life and that was in battle. She furthers her case with the image of Rostam tearing out Sohrāb’s gerdgāh. By ripping apart where the umbilical cord of Sohrāb once had been, that very means through which the mother had nourished the child when he was in her womb, the father Rostam has shown himself to be as viciously non-nurturing as the mother Tahmina is nurturing. He is the antithesis of what she is. She is Sohrāb’s generator, Rostam is his destroyer.

holding you to my breast during the long days and nights.

Now it is drowning in blood

a shroud has become the tattered garment covering your breast and shoulder.

Whom can I now draw to my side?

Who will forever be my confidant [ghamgosār]?

Whom can I summon in your place?

To whom can I tell my personal pain and sorrow?

Tahmina now shifts the attention away from Rostam and back to Sohrāb as she once again addresses him directly. She recollects her role as a young mother, cherishing the body, her nursling, and then bitterly declares it was all for nothing. She also contrasts her protective and continuous caring for her child with his present defenseless and sunken condition. Although Rostam is to blame for Sohrāb’s destruction, Tahmina now blames her own son, not her husband. By dying, Sohrāb has abandoned her. He has squandered her care. Now she is alone and has nobody. As she accuses Sohrāb of abandoning her when she asks him whom can she hold in her arms, who will be her ghamgosār, or confidant, who will sit next to her, and to whom will she tell about her pain and her sorrow, she is also blaming her son Sohrāb for not bringing her husband Rostam back to her — bringing him back to fulfill his role as a husband. Rostam should be the one to fulfill the role of a confidant to Tahmina — someone to fill her aching, lonely arms. She addresses her son as if he were her lover who had abandoned her. He was everything to her and she had given her life to him. How dare he leave her?

all stay in the dust, away from the palace and garden.

You searched for your father, O Lion, O Army Protector

in place of your father, you came upon your tomb.

With affliction you pass from hope to despair

you are miserably bent into the earth.

As she bewails his body, the very body that she had nurtured and that Rostam had failed to appreciate, she also bewails that his body now lies in the dust, not in the splendor to which it is entitled. The timbre is more general, and can apply to any young man, cut down in his prime, thereby inviting the audience to think beyond Sohrāb and about others in a similar plight. The awful truth that is peculiar to this story, that Sohrāb did actually find what he was looking for (his father) — and look what it got him (a dagger in the liver from his own father’s hand) — is reshaped to look like a failed quest that ended with the hero’s death. Her addressing him as a mighty warrior who found his death instead of his quest makes her personal loss everyone’s loss. He has turned from hope to hopeless despair (zār meaning lamentation as well) since he is sleeping in the dust, enveloped by a lamentable condition (zārwār). So too the audience is now completely enveloped by despair and grief.

and sliced your silvery abdomen

why did you not show him that sign which your mother had given you? Why didn’t you make him mindful?

Your mother had given you a sign from your father.

Why did you not believe her?

Now your mother will remain a prisoner without you,

full of suffering and grief, pain and aches in the belly.

Why didn’t I fare along with you

when you turned your heart’s desire, the moon and the sun.

Rostam would have recognized me from afar,

(if you were) with me, O Son, he would have treated you humanely.

He would not have pitched a javelin at you,

he would not have demolished your bowels, O my son.

She concludes her lament by shifting inward again, away from public sympathy and away from public outrage to scolding her son for not doing as she had advised. She blames him for his death and blames him further for causing her such misery. Her temper is that of a mother scolding a child for being disobedient — and then pointing out the consequences of his irresponsible behavior. Now his death is his own fault because he could have prevented it if he had only listened to her. Finally, having blamed him, she blames herself. As any mother after the death of her child, she blames herself for not preventing it, even if there was nothing that she could have done about it. If only she had gone with him, then nothing would have happened to him. She fancies that Rostam would have recognized her from afar and embraced them both, instead of — and now she switches back to reality — what really happened, that Rostam stabbed Sohrāb, his very own son, in the liver.

I quote these threatening words for you in passage 7:

if you do not condemn them

to death or a life sentence —

you see this dagger?

I’ll go to the upper quarter

and if I can’t find a grown-up

I’ll grab a small child

and slay him like a lamb —

for mine was an only child

and they cut him to pieces.

Such words are threatening not only because of what they say but also, even more important, for what they are: a song of lament. The agenda of protest in a lament may be quite explicitly threatening, as here, or only implicitly so, as when a mother’s grief over the loss of a child in a war demoralizes the host of fighting men.

Hector’s wife: for no true messenger came to her

and told her any news, how her husband was standing his ground outside the gates.

I stop here at line 439. So we see that Andromache has not yet heard the news of Hector’s death at the hands of Achilles, and how Achilles is dragging behind his chariot the corpse of Hector outside the walls of Troy for all the Trojans to see. Hecuba, the mother of Hector and the mother-in-law of Andromache, is already lamenting, but Andromache has not yet heard anything. She is alone in her boudoir, weaving a web that tells its own story. I continue reading the translation where I left off, starting at line 440:

a purple [porphureē] fabric that folds in two [= diplax], and she was inworking [enpassein] patterns of flowers [ throna ] that were varied [poikila].

(As we know from other such scenes in archaic Greek poetry, the patterns of flowers that Andromache is weaving are a poetic substitute for a love song, which is morphologically parallel to the song of lament, as the work of Margaret Alexiou has shown. Let us continue where we left off, starting at line 442:)

to set a big tripod on the fire, so that there would be

a warm bath for Hector when he had his return [nostos] from battle.

There is a built-in irony here, because it was the task of womenfolk to bathe the body of fallen warriors who were near and dear to them. The narrative makes that clear in the lines that follow, starting with line 445. I resume my translation at line 445:

the hands of Achilles had brought him [= Hector] down. It was the work of Athena, the one with the look of the owl.

She [= Andromache] heard the wailing and the cries of oimoi coming from the high walls [purgos].

Her limbs shook, and she dropped on the ground her shuttle.

I stop here at line 448. I should note here that the cries of oimoi are cries uttered in songs of lament. Now let us continue with line 449:

“Come, I want two of you to accompany me. I want to see what has happened.

I just heard the voice of my venerable mother-in-law, and what I feel inside is that

my heart is throbbing hard in my chest right up to my mouth, and my knees down below

are frozen stiff. I now see that something bad is nearing the sons of Priam.

I stop here at line 453. We have just seen the narrative subjectivizing the feelings of Andromache. As we continue the reading, we come to the realization that Andromache must have been feeling her feelings of premonition even as she was weaving her love song, which was already modulating into a lament. She was simply trying to get away from hearing the spoken word of those who already knew the terrible truth. Now, in the lines that follow, she begins to recognize that truth in its terrible fullness. I continue reading, starting at line 454:

fear for my bold Hector at the hands of radiant Achilles.

I fear that he has got him cut off from the rest, putting him on the run toward the open plain,

and that he has put a stop to a manliness that has gone too far, the cause of so much sorrow.

In these lines, she is already second-guessing the failure of Hector. He should have been defensive, as his name implies, since Hector means Protector, but no, Hector just had to go on the offensive, and Achilles was too good for him. Here we see a most painful distillation of feelings of demoralization and grief over the consequences of Hector’s failure. And now, in the lines that follow, Andromache begins to blame Hector for his shortcomings, just as we saw in Persian epic how the figure of Tahmina blames both her husband and her son for their shortcomings. As we continue our reading, we see that Andromache elaborates on the shortcomings of Hector, how he simply couldn’t resist going on the offensive when he should have stayed on the defensive. She describes this urge of Hector as a fatal shortcoming that had a demonic force of its own. Here is how she says it, as we continue our reading, starting at line 458:

Instead, he would keep on running ahead of the rest of them, not yielding to anyone as he pushed ahead with his vital force [menos].”

I stop here at line 459. As Andromache finishes speaking to her handmaidens, she has not yet even started her lament. She has not yet even seen the corpse of Hector. But, somehow, she already knows. Now we continue at line 460:

with heart throbbing. And her attending women went with her.

I stop here at line 461. We have just seen Andromache compared to a maenad, that is, to a woman possessed by Dionysus — a woman who has lost all her inhibitions in public. As we will see in a moment, her uninhibited appearance is manifested primarily in the fact that her beautiful hair, so perfectly coiffed, will come completely undone when she finally sees the horrific scene of her husband’s corpse being dragged behind the chariot of Achilles outside the walls of Troy. I continue reading at line 462:

she stood on the wall, looking around, and then she noticed him.

There he was, being dragged right in front of the city. The swift chariot team of horses was

dragging him, far from her caring thoughts, back toward the hollow ships of the Achaeans.

As the terrible image is imprinted on Andromache’s mind, this image starts receding, along with the body of her beloved husband. With the receding of the terrible image, her consciousness also recedes. She experiences a blackout. I continue reading at line 466:

and she fell backward, gasping out her life’s breath [psukhē].

So Andromache falls into a swoon — which is like death, because her breath of life is knocked out of her. And, at this point, her beautifully coiffed hair becomes completely disheveled. I continue reading at line 468:

– her frontlet [ampux], her snood [kekruphalos], her plaited headband [anadesmē],

and, to top it all, the headdress [krēdemnon] that had been given to her by golden Aphrodite

I stop here at line 470. The eroticism of the undone hair is enhanced by the reference to Aphrodite, goddess of sensuality and love, whose metonymic presence is invoked by the memory of those happy days, back when Andromache was married to Hector on her wedding day. I continue reading at line 471:

out from the palace of Eëtion, and he gave countless courtship presents.

These escapist memories of past happiness set the tone for what Andromache will sing as her lament when she recovers from her swoon. I continue reading at line 473:

and they were holding her up. She was barely breathing, to the point of dying.

But when she recovered her breathing and her life’s breath gathered in her lung,

she started to sing a lament in the midst of the Trojan women, with these words:

“Hector, I too am wretched. For we were born sharing a single fate,

the two of us — you in Troy, in the palace of Priam,

and I in Thebe, the city at the foot of the wooded mountain of Plakos

in the palace of Eëtion, who raised me when I was little

– an ill-fated father and a daughter with an equally terrible fate. If only he had never fathered me.

But now you [= Hector] are headed for the palace of Hades inside the deep recesses of earth,

that is where you are headed, while I am left behind by you, left behind in a state of hateful mourning [penthos],

a widow in the palace. And then there is the child, not yet bonded to you, so young he is,

whose parents we are, you and I with our wretched fate. And you will not be for him —

no you will not, Hector — of any help, since you died, nor will he be of any help for you.

I stop here at line 486. The lament of Andromache has captured beautifully the happy memories of the past and the terrible awareness of the present and future, with all the dangers that Hector has brought upon his loved ones. At this point, Andromache’s song modulates into a scene of terror and pity as she visualizes the dire fate of the son of Hector and Andromache. I continue at line 487:

still, for the rest of his life, because of you, there will be harsh labor for him,

and sorrows. For others will take his landholdings away from him. The time of bereavement

leaves the child with no agemates as friends.

He bows his head to every man, and his cheeks are covered with tears.

The boy makes his rounds among his father’s former companions,

and he tugs at one man by the mantle and another man by the tunic,

and they pity him. One man gives him a small drink from a cup,

enough to moisten the boy’s lips but not enough to moisten his palate.

But another boy whose parents are living hits him and chases him from the banquet,

beating him with his fists and abusing him with words:

“Get out, you! Your father is not dining with us!”

And the boy goes off in tears to his widowed mother,

the boy Astyanax, who in days gone by, on the knees of his father,

would eat only the marrow or the meat of sheep that were the fattest.

And when sleep would come upon him after he was finished with playing,

he would go to sleep in a bed, in the arms of his nurse,

in a soft bed, with a heart that is filled in luxury.

But now he will suffer many things, deprived of his father,

our child Astyanax, as the Trojans call him by name.

That is what he is called because you all by yourself guarded the gates and long walls.

I stop here at line 507. In the end, Andromache’s son will be a disappointment to her because her husband had been a disappointment. And now, in a crescendo of terror and pity, Andromache evokes the image of the naked corpse that will no longer have the benefit of being clothed in the fabric of the love that she wove for him in her song of love and lament. I continue reading at line 508:

and you will be devoured by writhing maggots after the dogs have their fill of you.

There you lie, naked, while your clothes are lying around in the palace.

Fine clothes they are, marked by pleasurable beauty [ kharis ], the work of women’s hands.

But I will incinerate all these clothes over the burning fire.

You will have no need for them, since you will not be lying in state, clothed in them.

But there is to be glory [kleos] (for you) from the men and women of Troy.”

So she [= Andromache] spoke, weeping, and the women mourned in response.

Despite all this demoralization, Andromache’s lament ends on a note of kleos or ‘glory’, which is the Homeric word that designates the medium of epic — the medium in which Andromache’s songs of lament are embedded. So the demoralization of the woman’s lament is counteracted by the glory of epic.

“Don’t befriend the dead.

You won’t stay here for a long time.

Be equipped and don’t fashion delay.

On a day your father gave you the drum roll (nowbat).

Is it all right if the drum roll comes to an end for you?

Thus his secret does not become manifest.

When in bewilderment, you seek, you will not find the key.

No one knows how to open the firmly shut door.

In this anguish your life returned to the wind.

However, when he passes on from the judgment

thus is the judgment from our Lord.

Don’t bind your heart to the ephemeral otherworld.

The ephemeral is not sufficiently profitable.”

It seems as if Tahmina’s rhetoric, in pretending that Sohrāb is not dead and still looking for his father, is maintained by Bahrām’s speech, but for different ends. Bahrām is in effect asking the restless spirit of the dead to stop looking for his father. In the upside-down and inside-out world created by Tahmina’s lament, it is the realm of the dead, not of the real world, that is ephemeral. Since Sohrāb continues to be addressed as if he were still alive, the ephemeral world of the living can be reassigned to the world of the dead. In this way, the words of Bahrām can unthink the implicit threat of revenge from the restless spirit of the dead son of Rostam. The threat conjured up by Tahmina’s words of lament can now be dissipated into the insubstantial shades of the dead.

Appendix

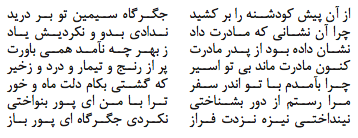

1. Shāhnāma ed. Mohl Vol. II, p. 188 lines 1407–1410:

Where are you now? Mingled with the dust?

When my eyes were fixed on the road I said

“Perhaps I will learn news of my child and Rostam.”

My gomān [“fancy” or “suspicion”] was thus, and I said,

“now you are wandering around the world,

searching continuously, and now, having found your father,

you now hasten to return.”’

2. Shāhnāma ed. Mohl Vol. II, p. 188 line 1411

3. Shāhnāma ed. Mohl Vol. II, p. 188 lines 1412–1413

Had he no pity upon your middle [gerdgāh] — that very thing which Rostam lacerated with his sword?’

4. Shāhnāma ed. Mohl Vol. II, p. 188-90 lines 1414–1417

Now it is drowning in blood a shroud has become the tattered garment covering your breast and shoulder.

Whom can I now draw to my side? Who will forever be my confidant [ghamgosār]?

Whom can I summon in your place? To whom can I tell my personal pain and sorrow?

5. Shāhnāma ed. Mohl Vol. II, p. 190 lines 1418–1420

You searched for your father, O Lion, O Army Protector in place of your father, you came upon your tomb.

With affliction you pass from hope to despair you are miserably bent into the earth.

6. Shāhnāma ed. Mohl Vol. II, p. 190 lines 1421–1427

why did you not show him that sign which your mother had given you? Why didn’t you make him mindful.

Your mother had given you a sign from your father. Why did you not believe her?

Now your mother will remain a prisoner without you, full of suffering and grief, pain and aches in the belly.

Why didn’t I fare along with you when you turned your heart’s desire, the moon and the sun.

Rostam would have recognized me from afar, (if you were) with me, O Son, he would have treated you humanely.

He would not have pitched a javelin at you, he would not have demolished your bowels, O my son.

7. From a live recording of a lament sung by widow Vrettis from Mani in the Peloponnese:

8. Iliad XXII 437–515

Hector’s wife: for no true messenger came to her

and told her any news, how her husband was standing his ground outside the gates.

440 She [= Andromache] was weaving [huphainein] a web in the inner room of the lofty palace,

a purple [porphureē] fabric that folds in two [= diplax], and she was inworking [en passein] patterns of flowers [throna] that were varied [poikila].

And she called out to the attending women, the ones with the beautiful tresses [plokamoi], in the palace

to set a big tripod on the fire, so that there would be

a warm bath for Hector when he had his return [nostos] from battle.

445 Unwary [nēpiē] as she was, she did not know [noeîn] that, far from the bath,

the hands of Achilles had brought him [= Hector] down. It was the work of Athena, the one with the look of the owl.

She [= Andromache] heard the wailing and the cries of oimoi coming from the high walls [purgos].

Her limbs shook, and she dropped on the ground her shuttle.

And then she stood among the women slaves attending her, the ones with the beautiful tresses, and she spoke to them:

450 “Come, I want two of you to accompany me. I want to see what has happened.

I just heard the voice of my venerable mother-in-law, and what I feel inside is that

my heart is throbbing hard in my chest right up to my mouth, and my knees down below

are frozen stiff. I now see that something bad is nearing the sons of Priam.

If only the spoken word had been too far away for me to hear. But I so terribly

455 fear for my bold Hector at the hands of radiant Achilles.

I fear that he has got him cut off from the rest, putting him on the run toward the open plain,

and that he has put a stop to a manliness that has gone too far, the cause of so much sorrow.

It was a thing that had a hold over him, since he could never just stand back and blend in with the multitude of his fellow warriors.

Instead, he would keep on running ahead of the rest of them, not yielding to anyone as he pushed ahead with his vital force [menos].”

460 So speaking she rushed out of the palace, same as a maenad [mainás],

with heart throbbing. And her attending women went with her.

But when she reached the tower and the crowd of warriors,

she stood on the wall, looking around, and then she noticed him.

There he was, being dragged right in front of the city. The swift chariot team of horses was

465 dragging him, far from her caring thoughts, back toward the hollow ships of the Achaeans.

Over her eyes a dark night spread its cover, and she fell backward,

gasping out her life’s breath [psukhē].

She threw far from her head the splendid adornments that bound her hair

— her frontlet [ampux], her snood [kekruphalos], her plaited headband [anadesmē],

470 and, to top it all, the headdress [krēdemnon] that had been given to her by golden Aphrodite

on that day when Hector, the one with the waving plume on his helmet, took her by the hand and led her

out from the palace of Eëtion, and he gave countless courtship presents.

Crowding around her stood her husband’s sisters and his brothers’ wives,

and they were holding her up. She was barely breathing, to the point of dying.

475 But when she recovered her breathing and her life’s breath gathered in her lung,

she started to sing a lament in the midst of the Trojan women, with these words:

“Hector, I too am wretched. For we were born sharing a single fate,

the two of us — you in Troy, in the palace of Priam,

and I in Thebe, the city at the foot of the wooded mountain of Plakos

480 in the palace of Eëtion, who raised me when I was little

— an ill-fated father and a daughter with an equally terrible fate. If only he had never fathered me.

But now you [= Hektor] are headed for the palace of Hades inside the deep recesses of earth,

that is where you are headed, while I am left behind by you, left behind in a state of hateful mourning [penthos],

a widow in the palace. And then there is the child, not yet bonded to you, so young he is,

485 whose parents we are, you and I with our wretched fate. Neither will you be for him,

no you will not, Hektor, of any help, since you died, nor will he be of any help for you,

even if he escapes the attack of the Achaeans, with all its sorrows,

still, for the rest of his life, because of you, there will be harsh labor for him,

and sorrows. For others will take his landholdings away from him. The time of bereavement

490 leaves the child with no agemates as friends.

He bows his head to every man, and his cheeks are covered with tears.

The boy makes his rounds among his father’s former companions,

and he tugs at one man by the mantle and another man by the tunic,

and they pity him. One man gives him a small drink from a cup,

495 enough to moisten the boy’s lips but not enough to moisten his palate.

But another boy whose parents are living hits him and chases him from the banquet,

beating him with his fists and abusing him with words:

“Get out, you! Your father is not dining with us!”

And the boy goes off in tears to his widowed mother,

500 the boy Astyanax, who in days gone by, on the knees of his father,

would eat only the marrow or the meat of sheep that were the fattest.

And when sleep would come upon him after he was finished with playing,

he would go to sleep in a bed, in the arms of his nurse,

in a soft bed, with a heart that is filled in luxury.

505 But now he [= our child] will suffer many things, deprived of his father,

our child Astyanax, as the Trojans call him by name.

That is what he is called because you all by yourself guarded the gates and long walls.

But now, you are where the curved ships [of the Achaeans] are, far from your parents,

and you will be devoured by writhing maggots after the dogs have their fill of you.

510 There you lie, naked, while your clothes are lying around in the palace.

Fine clothes they are, marked by pleasurable beauty [kharis], the work of women’s hands.

But I will incinerate all these clothes over the burning fire.

You will have no need for them, since you will not be lying in state, clothed in them.

But there is to be fame [kleos] [for you] from the men and women of Troy.”

515 So she [= Andromache] spoke, weeping, and the women mourned in response.

9. Shāhnāma ed. Mohl Vol. II, p. 192 lines 1452–1458

You won’t stay here for a long time. Be equipped and don’t fashion delay.

On a day your father gave you the drum roll (nowbat). Is it all right if the drum roll comes to an end for you?

Thus his secret does not become manifest. When in bewilderment, you seek, you will not find the key.

No one knows how to open the firmly shut door. In this anguish your life returned to the wind.

However, when he passes on from the judgment thus is the judgment from our Lord.

Don’t bind your heart to the ephemeral otherworld. The ephemeral is not sufficiently profitable.”