We had the chance to sit down with CHS author Malcolm Davies to talk about his new book, The Aethiopis: Neo-Neoanalysis Reanalyzed, available in print through Harvard University Press and forthcoming online from the Hellenic Studies Series. Enjoy!

Q. What was your overall goal in writing this book, and how does it fit into your own research?

For me the most interesting aspect is how the topic exemplifies and illustrates a big general issue, narrative in literature and visual art: how, and how significantly, do they differ? I have long planned a book on this general topic and discuss the topic further below.

Q. The subtitle of your book is Neo-Neoanalysis Reanalyzed. What is Neo-Neoanalysis?

I confess this is perhaps too crude, glib and jokey a term, which may well not survive. I thought it might attract attention and interest. To deconstruct and reconstruct it: Analysis in nineteenth century German classical studies was the apportioning of different parts of Homer’s epics, especially the Iliad, to different authors of differing dates. In the twentieth century the (initially American) perception that the Homeric epics’ style is ‘formulaic’ and thus characteristic of other poems, known to be oral in composition and transmission, seemed to many to render Analysis an inappropriate tool. At about the same time, Neo-analysis, again a mainly German phenomenon, was a rather different approach to either of the foregoing, and apportioned different parts of the Iliad not so much to different authors as to different ‘sources’ used by the same author. But the question then arises whether the notion of ‘sources’ is appropriate, given the issue of orality. I thought the term Neo-Neo-analysis might be applied to an approach developing in the late twentieth and early twenty first centuries which employed with more subtlety and discretion the presuppositions of Neo-Analysis.

Q. At the end of chapter one you quote a statement by Jonathan Burgess written in 1997, “If we can embrace Neo-Analysis as a ‘working hypothesis,’ we still need to scrutinize its propositions one by one, rejecting and accepting them as seems appropriate.” On some level, this seems to describe your process throughout the book. Would you agree with that statement? And if so, why do you think this kind of scrutinizing is still necessary twenty years later?

My first reaction is (again!) perhaps too glib and jokey, that in the world of classical scholarship, 20 years is not a long time. More seriously, I would argue, as just implied above, that in the first decade and a half of the present century J.B. and others have done and are currently doing important work that renders more subtle and sophisticated approach to the understanding of the issues identified above. The posing of this particular question has suggested to me what I hope is a suggestive analogy (not an exact parallel): from the sphere of textual criticism and the history of Greek and Latin texts. In the nineteenth century the tendency was to try to identify the ‘best’ MS and use this criterion to decide automatically between variant readings. In the first half of the twentieth century (partly due to the great A.E. Housman) this was recognised as too simplistic. Methodologically, whether x is the best MS or not can only be seen at the end (not the start) of the process, after each variant reading has been decided on its own merits, not as the result of an initial preconception. This intuition seems to me analogous to the point J.B. is making, and the more pragmatic approach common to both spheres strikes me as characteristic of a wider change in classical studies away from rather optimistic and simplistic notions of a single solution that unlocks the key to everything and can be applied to all problems.

Q. In this book you argue for a complex, interdependent relationship between the Aethiopis and the Iliad. How did you come to this conclusion? And what is the significance of such a relationship for both ancient performers and their audiences?

Many would say this is the most important aspect of the topic. It is certainly the most complex—too complex even to summarise here. Briefly, similarities of story pattern between certain episodes of the Iliad and (as revealed by the late prose summary and other possible sources, e.g. visual art) the Aethiopis have suggested to some that the Aethiopis was earlier than, and inspired those episodes of, the Iliad. Other have thought exactly the reverse. A resolution more in keeping with e.g. the complexities of oral poetry and other related issues might suggest e.g. that an earlier version of the Aethiopis influenced the Iliad – which could nevertheless be older than the Aethiopis as we now know it from the sources mentioned in parenthesis above.

Q. Why was it important to you to also consider the relationship between the verbal and visual art depicting scenes such as the Kerostasia/Psychostasia? How has this visual art helped to define your thinking about the Aethiopis?

Q. Why was it important to you to also consider the relationship between the verbal and visual art depicting scenes such as the Kerostasia/Psychostasia? How has this visual art helped to define your thinking about the Aethiopis?

As indicated at the start, this is what I have always found the most interesting aspect, the evidence of visual art, esp. vase paintings, which depict scenes, e.g. the duel of Achilles and Memnon, which we know from a late prose summary of the Aethiopis’ contents, to have featured in that lost epic. We should avoid regarding these as illustrations, a potentially anachronistic term (and, incidentally, even in nineteenth century novels by, e.g. Dickens, the relation between text and accompanying illustration can be more complex and problematic than usually realised). If these depictions show details not mentioned in the prose summary, do they reflect details in the lost epic, or are they the sorts of things (e.g the shape of the psychai in the Kerostasia) a visual artist would add from purely visual motives?

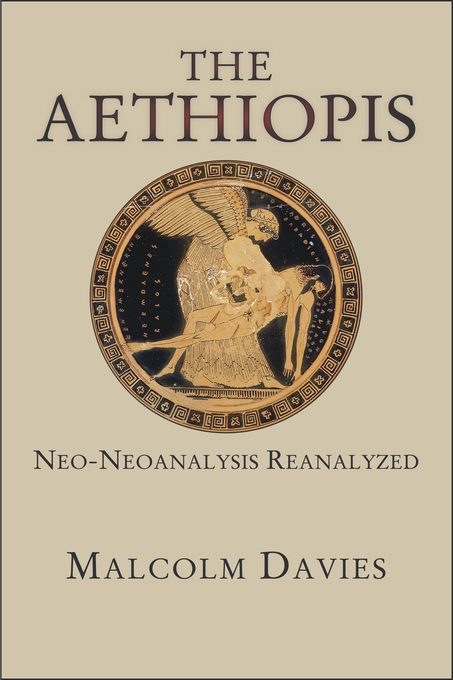

Q. Can you tell us about the image on the cover of the book? What does it depict and why did you select that as the cover?

This is a red-figure vase painting which shows his divine mother recovering the corpse of Memnon who has been killed by Achilles. Since the Aethiopis is named after this Ethiopian ally of the Trojans it seemed appropriate for the cover. The late prose summary tells us that Memnon was carried off to an immortal afterlife by his mother.

Q. In your appendix you discuss the Tabulae Iliacae. Why are these works unique in terms of the visual representation of epic themes, and what can they teach us about the Aethiopis?

In the case of the Tabulae Iliacae, the use of the term ‘illustration’ is more tempting and perhaps less misleading, since these small Roman tablets of marble from c. first century A.D. not only contain visual depictions of poems (both lost, like the Aethiopis, and also extant, like the Iliad), but the scenes are captioned and accompanied by brief prose summaries of the contents of the poems depicted. When we can check depiction against extant poem, as with the Iliad, they seem relatively accurate; but we cannot be utterly sure that the artist knew the original text of e.g. the Aethiopis rather than working from a later, and perhaps unreliable, synopsis.

Q. What projects are you currently working on?

This includes a further commentary on a lost poem from the Epic Cycle, the Cypria, a sort of ‘prequel’ to the Iliad, to use modern jargon: the relationship between the two poems raises the same sort of issues as that between Aethiopis and Iliad. Since the Aethiopis could be regarded as a ‘sequel’ to Homer’s epic, I plan to include at the end an Appendix cross-referring to it and dealing with further studies of its issues that appeared too late for me to do justice in the present book.

Malcolm Davies is Professor of Greek Language and Literature at St. John’s College, University of Oxford.

Readers might also enjoy The Theban Epics by the same author, available online on the CHS website.