Stephanie Lindeborg

Stephanie LindeborgWe recently had the opportunity to interview Stephanie Lindeborg, a senior at Holy Cross and an undergraduate researcher working with Prof. Mary Ebbott and Prof. Neel Smith on the Homer Multitext project. [Read our companion interview with Mary Ebbott.] Stephanie shared her thoughts about working with treasured primary resources such as the Venetus A, the joys of discovery, and the unique experience of working on the Homer Multitext. You can also read about this young scholar’s research in her guest post on the Homer Multitext blog, where she discusses her investigation of marginal notes in red ink in the first few folios of the Venetus A,

CHS: Tell us a little bit about yourself and your educational experience. Why did you choose to study Classics in college?

S.L.: I’m a rising senior at the College of the Holy Cross. I came in declared as a Classics major. I was lucky to have Latin since sixth grade and loved it the entire time. I’ve always been really fond of the languages. I figured it out towards the end of my high school career that I wanted to be a Classics major and Holy Cross was one of my best options for undergrad Classics. I haven’t regretted anything since. It’s been a wonderful three years. I spent the last year in Athens and Rome studying abroad and this is my second, going on third, year of research on the Multitext project. I plan on working on a thesis with the Escorial Υ.1.1 and the Venetus A this year while looking at applying to grad schools.

CHS: What is the Homer Multitext project and how are you participating? How has this educational experience differed from your traditional classroom work?

S.L.: The Homer Multitext project is a revolutionary online database. It hosts every manuscript of Homer that we can get our hands on. The goal is to treat each manuscript as its own historical artifact to help us recreate the oral tradition of Homer and the tradition of ancient Homeric scholarship. We start with the digital images of a manuscript. From those we create an edition of the main text, which is true to every feature of the text, even if some editors might correct it as “wrong.” Then we individually image the scholia, which are scholarly commentaries, some of which date back as far as the 3rd century BC. The next step is to read these scholia and create a digital edition of the text of every single scholion. Of course, we also run into a lot of other features that aren’t the main text or the scholia, so we have to account for those too. We have many image repositories for things like critical signs (asterisks, diples, etc.) and quire numbers (which are the numerals that organize the folios into sections for binding [more on this below]).

As for me, I started off my sophomore year working on reading the main text of the Venetus A every Friday afternoon. That turned into creating paleographic guides to help other people learn to read the Venetus A. I was asked to do summer research at Holy Cross the summer of 2011 with two of my peers. We completed an edition of Book 1 of the Venetus A that summer, as well as a little bit of Book 5, which was started at the Center of Hellenic Studies. I picked up my research again this summer after being abroad, and we’re almost done with our edition of Book 2 of the Escorial Υ.1.1, as well as a little bit of Book 3. I plan on staying involved throughout my entire senior year. While I was away the Holy Cross Manuscripts, Inscriptions, and Documents Club became a Registered Student Organization, and I’ll be serving as its Vice President. These experiences are really unlike anything else I could have possibly experienced in the classroom. There isn’t another school out there offering this kind of experience on this scale to undergrads. Most scholars doing this kind of work already have their doctorates. It makes you realize that there is so much more to do in Classics and that previous scholarship isn’t enough. I can honestly say that there is so much we don’t know that’s worth looking into.

CHS: What does it feel like to contribute to the ongoing scholarship on some of the most important manuscripts in the western tradition? Can you share a memorable moment from your time on the HMT?

S.L.: Every now and then I have to remind myself what a big deal this really is. It’s easy, when I’m working with some of my really good friends and having a lot of fun doing it, to forget that we’re working with primary sources of the Iliad and the scholia, and that we’re doing something that is both new and incredibly important to understanding our epic traditions. The students that are working in the lab at Holy Cross know these manuscripts better than pretty much anyone else on the planet right now, and probably even better than the scholars who gave us our previous editions. There’s nothing more rewarding than knowing just how valuable our work and our skills are.

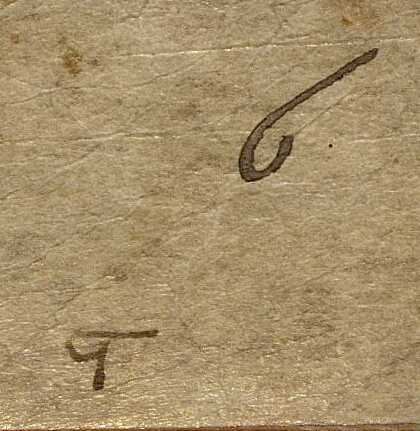

Image: detail from 40r of the Escorial Υ.1.1. The letter stigma, which means 6, along with the Arabic numeral 6.

Image: detail from 40r of the Escorial Υ.1.1. The letter stigma, which means 6, along with the Arabic numeral 6.The best thing about this research is that almost every day is a new discovery. At the end of last week, we were the first people to ever figure out the quire arrangement of the Venetus B and the Escorial Υ.1.1. Quires, or gathers, are sets of leaves of parchment or paper, folded one within the other, that comprise a codex manuscript. Essentially they’re sets of folios that go together and are numbered so that when the scribe is done writing everything is bound together in the proper order. Understanding this arrangement is really helpful when you’re trying to figure out when certain features were written in or why things might be missing. When I asked Prof. Smith and Prof. Ebbott about the quire arrangement, they didn’t have any answers. No one had published anything on it before, but I spent an entire Thursday finding all the numbers in the Υ.1.1. My partner, Neil, worked on the Venetus B. For the most part these two manuscripts are considered twins, so we wondered if they would have similar quire arrangements. As it turns out, not only are they totally different, but the Υ.1.1 has one of the weirdest quire arrangements ever.

CHS: How has this experience enriched your life beyond advancing your academic goals, and what are your plans as a young classicist? Do you see your passion for Greek language, Homeric poetry and learning as an integral part of your life going forward?

S.L.: Working on the Homer Multitext has taught me a lot of things besides just some practical skills. It’s taught me to think like a revolutionary. Being a Classicist doesn’t mean I have to sit in a dusty office for the rest of my life and contemplate philosophy, not that there’s really all that much wrong with that. But I can also break the expected mold. I can and should take advantage of all that technology has to offer. There’s so much more we can understand if we use tools from across the academic disciplines, not just the obvious ones. As a rising senior, I’ve been giving a lot of thought about where I’m going to be a year from now. My plans are to go to grad school and pursue a PhD in Classical Philology. Homer and scholia have a special place in my heart, and I’d love to keep working on manuscripts forever, but I’m also interested in Latin and Greek prose, especially history, so that’s something I plan to continue studying Classics. I’ve been very fortunate so far in my Classics career. I’m lucky to be at Holy Cross and provided with all the opportunities I’ve had there. I’ve worked hard and I’ve had great advisors. Hopefully I’ll keep up this streak in grad school. I’d love to see the Homer Multitext project spread to other institutions, and I hope that I’ll get to be a part of that diffusion of knowledge. After all, the HMT is all about sharing what we do.

****

For more insight into the excellent undergraduate research being done through the Homer Multitext Project, be sure to read the following posts on the HMT blog: Christine Roughan’s post on the numbering of the similes in the Venetus A manuscript, and Thomas Arralde’s post on identifying Aristarchean commentary in the Venetus A scholia.

S.L.: Working on the Homer Multitext has taught me a lot of things besides just some practical skills. It’s taught me to think like a revolutionary. Being a Classicist doesn’t mean I have to sit in a dusty office for the rest of my life and contemplate philosophy, not that there’s really all that much wrong with that. But I can also break the expected mold. I can and should take advantage of all that technology has to offer. There’s so much more we can understand if we use tools from across the academic disciplines, not just the obvious ones. As a rising senior, I’ve been giving a lot of thought about where I’m going to be a year from now. My plans are to go to grad school and pursue a PhD in Classical Philology. Homer and scholia have a special place in my heart, and I’d love to keep working on manuscripts forever, but I’m also interested in Latin and Greek prose, especially history, so that’s something I plan to continue studying Classics. I’ve been very fortunate so far in my Classics career. I’m lucky to be at Holy Cross and provided with all the opportunities I’ve had there. I’ve worked hard and I’ve had great advisors. Hopefully I’ll keep up this streak in grad school. I’d love to see the Homer Multitext project spread to other institutions, and I hope that I’ll get to be a part of that diffusion of knowledge. After all, the HMT is all about sharing what we do.

****

For more insight into the excellent undergraduate research being done through the Homer Multitext Project, be sure to read the following posts on the HMT blog: Christine Roughan’s post on the numbering of the similes in the Venetus A manuscript, and Thomas Arralde’s post on identifying Aristarchean commentary in the Venetus A scholia.