By Rebecka Lindau, Chief Librarian

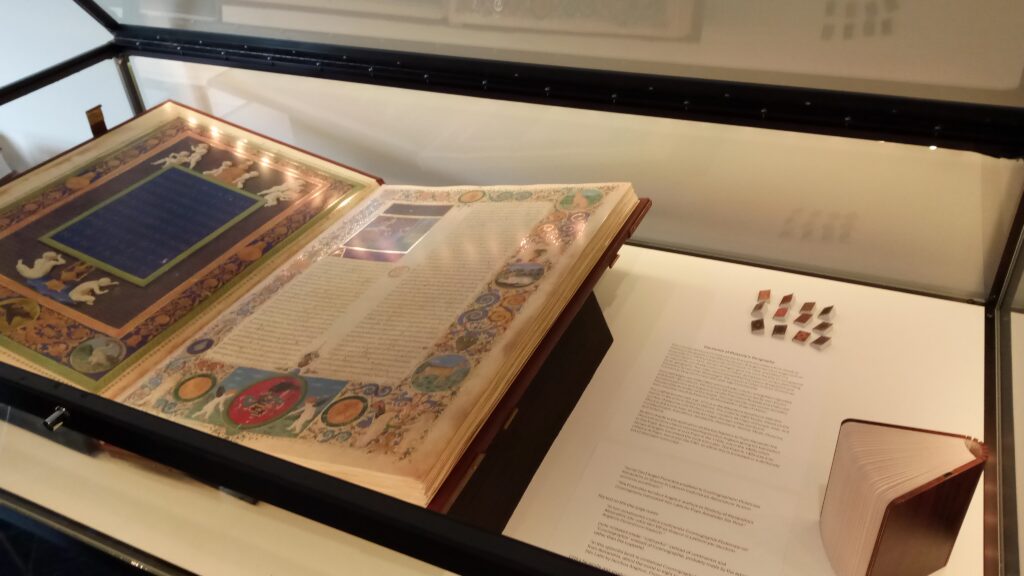

Two famous and exquisite manuscript facsimiles are on display at the Center for Hellenic Studies. Both are of texts and images by ancient Greek writers, one a geographer, mathematician, astronomer, music theorist, and philosopher living in the 2nd century CE, Claudius Ptolemaios, and the other a medical doctor, Pedanius Dioscorides living in the 1st century CE. Both were revolutionary for their time and their work were authoritative texts in their fields for more than a thousand years. The original manuscripts are in the Vatican and Vienna respectively, one is from the Italian renaissance and the other from Byzantium, the Greek middle ages.

Both works offer fascinating glimpses of almost two thousand years of science, mathematics, astronomy, astrology, history, religion, medicine, and magic. While they are enchanting and beautiful objects, they also demonstrate that antiquity offers a unique and potent knowledge base to inspire and educate subsequent cultures, including our own.

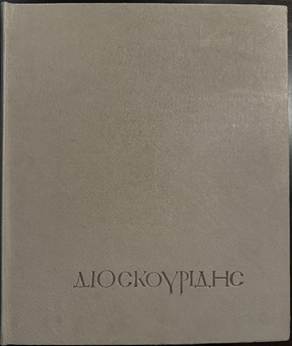

The Vienna Dioscorides

The original manuscript of the so-called Vienna Dioscorides (Codex Vindobonensis med. Gr. 1) is dated to ca. 512 and is held in the Österreichische Nationalbibliothek, Vienna. Facsimile: Graz: Akademische Druck- u. Verlagsanstalt, 1965-1970.

This work with the Greek title Περὶ ὕλης ἰατρικῆς or as it is commonly known in western Europe in Latin, De materia medica, about herbal or pharmaceutical materials, was written by Πεδάνιος Διοσκουρίδης. We do not know much about Dioscorides. We know that he was born in the ancient city of Anazarbus, as he is referred to by contemporary sources as Dioscorides of Anazarbus, which was a town in Cilicia, Asia Minor, now more or less corresponding to Armenia near Cyprus and Syria some 2,000 years ago in the first century of the Common Era. He is thought to have been a doctor in the Roman army under emperors Claudius and Nero, and as doctors were in those days, he would also have been a botanist and pharmacologist, or herbalist since ancient medicine was based largely on herbs.

The codex is a kind of encyclopedia, a pharmacopeia, in 5 volumes. In volume 1, for example, we learn about aromatic plants used in ointments — everyday products used for personal hygiene. A nutritious diet, exercise, and hygiene were all emphasized in ancient Greek medicine. We learn that shampoo was made from walnut, soap from elm, toothpaste from myrrh, etc. Other volumes catalog plants used more for what we generally think of as medicine, to treat illnesses, rather than preventing them.

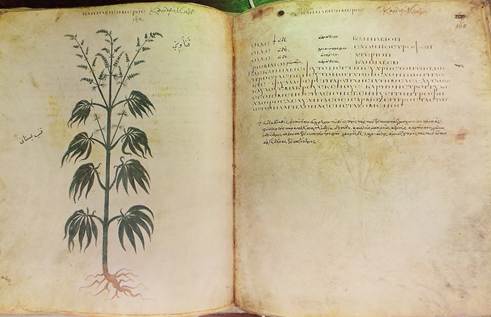

About a plant such as σίνηπι (sinepi) (fol. 310), mustard (above), Dioscorides writes that it is “suitable for hip diseases, and afflictions of the spleen, and treats baldness” (transl. Lily Y. Beck, Pedanius Dioscorides of Anazarbus, De materia medica, Olms-Weidmann, 2005);

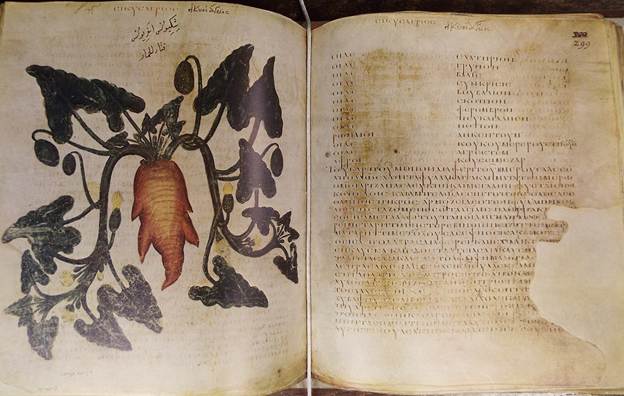

and about σῐ́κυς (sikus) (fol. 298v), cucumber (above), that it “eases the bowel; is appropriate to use for the bladder, and it revives those who faint if they should smell it” (transl. Lily Y. Beck, Pedanius Dioscorides of Anazarbus, De materia medica, Olms-Weidmann, 2005).

Fol. 223v: Μήκων ροϊάς, corn poppy …softens the bowel…treats inflammations…sleeping agent (transl. Lily Y. Beck, Pedanius Dioscorides of Anazarbus, De materia medica, Olms-Weidmann, 2005).

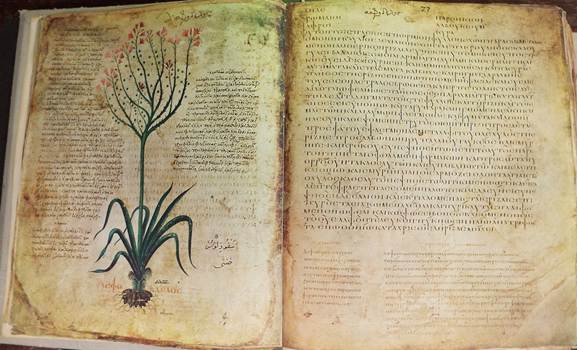

In examining the manuscript or book itself, we see that it is written in so called uncial script (seen to the right on the page above), an elegant, rounded letter script in all capital letters, popular from the 4th to the 8th century. Producing this very large, thick and tall, and heavy manuscript (37 × 31.2 cm − 491 folios, 982 pages) would have entailed the killing of several hundred animals, usually sheep, goats, and calves to produce the almost 500 folios made of vellum or parchment, animal skin. A folio consists of 2 pages, recto and verso, front and back, so almost 1,000 pages altogether. The manuscript contains ca. 400 extant, some are missing, full-page illustrations of medicinal plants describing in Greek (with later additions of plant names in Arabic, Hebrew, and several other languages) some 600 plants and many more herbal cures.

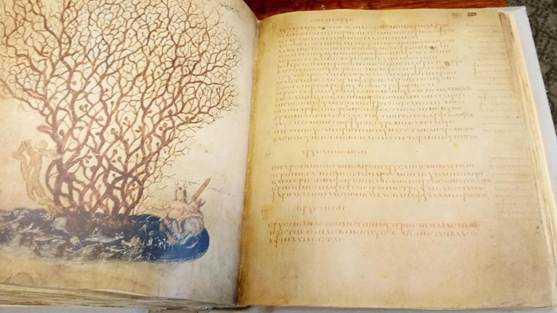

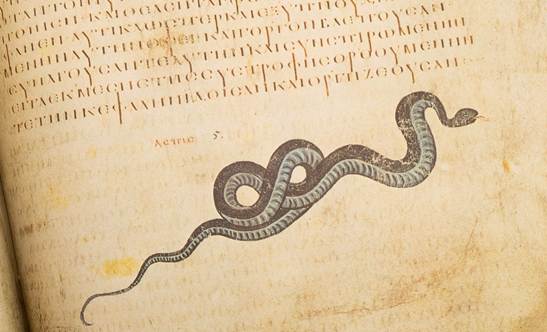

In addition to the text by Dioscorides, the manuscript has appended to it other interesting works such as a poem in hexameter (above) about herbs attributed to Rufus of Ephesus, another early physician; an ornithological treatise, in fact, the earliest preserved work on birds (see below), some 1700 years before Audubon, by a certain Dionysius, identified with either Dionysius of Philadelphia or Dionysius Periegetes, the author of a travel guide; and a work by Greek physician Nicander of Colophon on the treatment of snake bites (see below).

Dioscorides’ treatise most likely drew from his own observations of plants in western Turkey and eastern Greece, also as he moved with the Roman legions, and he had access to the great library of Alexandria, so he would also have researched earlier sources which for the most part have not survived such as those of Crateuas, nicknamed ὁ ῥιζοτόμος, the root cutter, roots forming an important part of a pharmacologist’s toolkit. Dioscorides himself credits Crateuas, but says that Crateuas’ treatise was incomplete, and of course many centuries of oral tradition, not the least based on the knowledge of anonymous female herbalists, doctors and midwives. In fact, many plant descriptions in De Materia Medica address the reproductive health of women. Also, the ancient Babylonians and Egyptians wrote accounts of curative herbs, which Dioscorides would have seen. And, certainly, he would have been familiar with the Greek philosopher Theophrastus in the 4th c. BCE who wrote his famous Historia Plantarum, Inquiry into Plants, describing plants from all corners of the then known world, also noting their curative properties.

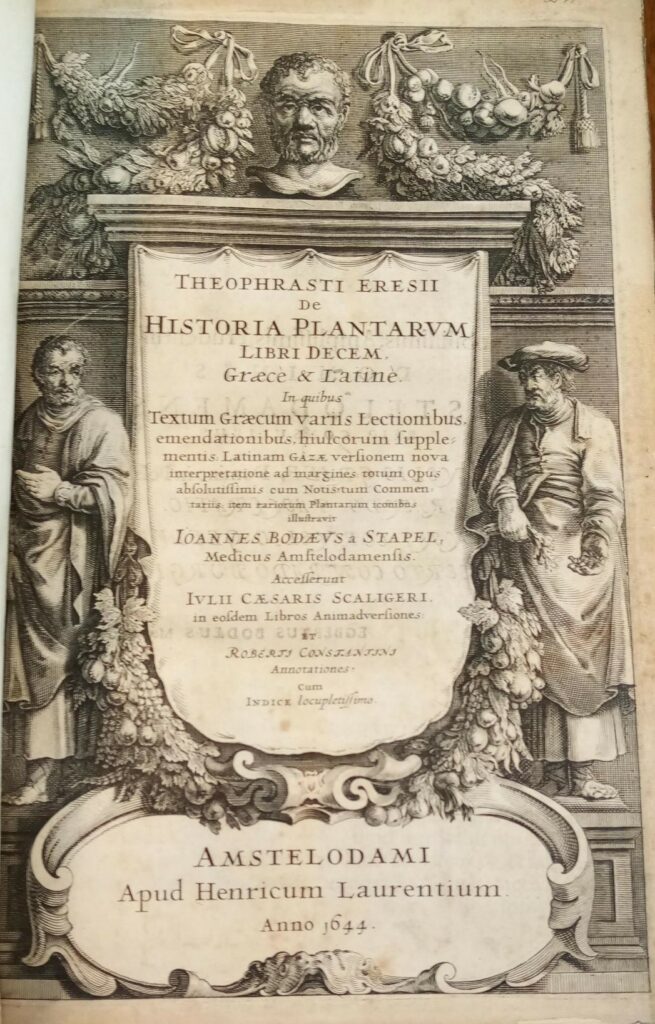

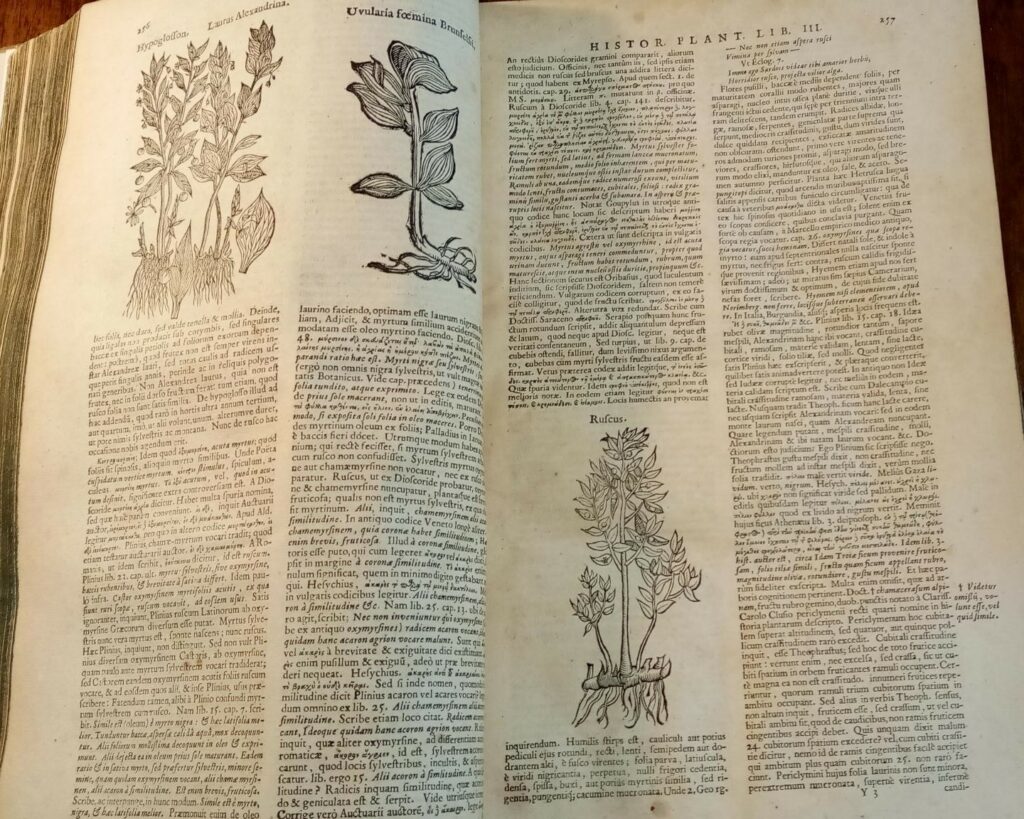

Theophrastus’ Historia Plantarum. Greek text with ample commentary, corrections, and emendations by Daniel Heinsius, Joseph Scaliger, Claudius Salmasius (Claude Saumaise), and Johannes Bodaeus van Stapel, with Latin translation by Theodorus Gaza. Amsterdam 1644. Rare Book and Manuscript Collection, Center for Hellenic Studies.

This Latin folio edition has 1,200 pages, with 50 woodcut illustrations.

The Vienna Dioscorides is not the only manuscript of De Materia Medica which has survived. In fact, there are many, a testament to its popularity. Some of the more important ones include a manuscript at a monastery on Mount Athos, and in libraries in Naples, New York, the Pierpont Morgan Library, and Michigan, the latter is the oldest and in the form of a papyrus-plant fragment. There are also a number of illustrated Arabic, Syriac, Persian and Indian manuscripts. However, among these early manuscripts the most famous and oldest illustrated treatise is our lavishly illuminated Vienna Dioscorides.

The original manuscript was created in the Byzantine capital Constantinople for an imperial princess, Anicia Juliana, who lived 462-527, the daughter of Anicius Olybrius who was one of the last of the Western Roman Emperors, thus it is sometimes referred to as the Juliana or Juliana Anicia codex. Interestingly, Boethius, the author of the influential De consolatione philosophiae, was a relative, and among her illustrious ancestors were none other than emperors Constantine and Theodosius, so Juliana’s lineage was as impeccable as her wealth was impressive. She financed several building projects in the capital, one of which was the Church of St. Polyeuctus, a monumental forerunner to the Hagia Sophia built some years later. The church has been excavated and is in ruins, fragments of which can be found incorporated into other churches as far away as in Basilica di San Marco in Venice thanks to Venetian crusaders (or marauders). Juliana’s life and influence speak to the prominent role of upper-class women in Byzantium, not the least as patrons of the arts.

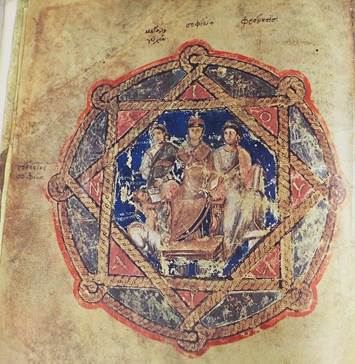

In addition to the plant and animal illustrations, the manuscript contains several full-page miniature paintings in the front matter. On folio 6 verso (above), for example, we see Anicia Juliana in the oldest extant dedication portrait. We do not know if perhaps the manuscript was commissioned by Juliana or simply dedicated to her as a token of gratitude for her financing the building of a church, which may also have served as a healing center.

There is a barely visible inscription, a poem, lauding Juliana for building a “temple of the lord” in the district of Honoratae, a suburb of Constantinople, identified with a church dedicated to Virgin Mary constructed in 512 C.E., providing an approximate date for the creation of the manuscript. Perhaps the portrait itself points to Juliana having also commissioned the manuscript as she is seated on a throne wearing purple and gold, red shoes, and a diadem, flanked by personifications of Μεγαλοψυχία (“Greatness of Soul,” a concept we know from Aristotle’s Nichomachaean Ethics) and which could have negative connotations as well but in this context is usually translated as “Magnanimity” or “Generosity,” and Φρονῆσις “Wisdom,” or “Practical Wisdom” often translated as “Prudence,” and a personification of Ἐυχαριστία τεκνῶν, “Gratitude for the Arts,” which in antiquity also included medicine, kneeling at Juliana’s feet and kissing her red shoe. Juliana in the meantime hands out or sprinkles gold coins into an open book. If this book is our codex, it is perhaps another clue that she in fact paid for its production. The handing out of gold coins was otherwise an act performed by a new consul taking office or by an emperor, so maybe Juliana also had political ambitions although both her husband and son were consuls, so the act of distributing gold coins could perhaps also be interpreted as an extension of her as a consul’s wife and mother, and an emperor’s daughter. Phronesis holds a large closed book with red cover and one of the putti has one as well. If this is our codex, it could indicate that initially it had a red cover.

Juliana sits in an eight-pointed star enclosed by a circle, formed by an intertwined rope or chain, which is an unusual iconography not easily interpreted, but is considered to have had an apotropaic, something that protects from harm, function, pointing to protection for both Juliana and her manuscript, perhaps not an entirely satisfactory explanation. The eight-pointed star in cosmology usually refers to the four elements and the four directions representing the universe. However, it is also reminiscent of monograms of Byzantine emperors, so perhaps this was Juliana’s monogram or that of her gens? The frame forms triangles in which the name Juliana (ΙΟΥΛΙΑΝΑ) is written in large gold letters — Iota, omicron, upsilon, lambda, iota, alpha, nu, alpha.

Much of the above is conjecture. What we do know from contemporary accounts is that the codex was used as a text or reference book in the imperial hospital of Constantinople and elsewhere throughout Europe and the Arabic and Ottoman east for many centuries. It was translated fully into Arabic in the tenth century. Plant names written in Latin, Hebrew, Turkish, Arabic, and several other languages demonstrate not only its popularity, but also its continued use and geographic reach.

Not many years after the production of the Vienna Dioscorides, many people in Mediterranean Europe and the Near East, including emperor Justinian were afflicted with a plague, the so-called Plague of Justinian, which no doubt would only have enhanced the use and significance of this pharmacopeia. Justinian recovered. It is not known which herbs may have aided his recovery although reading De Materia Medica one could perhaps venture a guess; for example, frankincense, juniper, lavender, and rosemary, all referenced as anti-plague medicines.

Fol. 26v. Ἀσφόδελος, asphodel…treats pain…coughs…ointment for the eyes…restores hair…a treatment for earache…and leprosy (transl. Lily Y. Beck, Pedanius Dioscorides of Anazarbus, De materia medica, Olms-Weidmann, 2005).

Still in Constantinople in 1406, extensive scholia, commentary (seen to the left on the page above), were added in Byzantine Greek minuscule, a cursive script, by a notary, later monk, called Ἰωάννης Χορτασμένος, commissioned for a monk and physician in the Monastery of St. John Prodromos where it was housed, and the manuscript was also rebound at this time.

After the Muslim conquest of the city in 1453, the codex fell into the hands of the Ottoman Turks, and Turkish and Arabic names were added to the Greek (seen to the right of the leaves in the plant image above). We also know that the manuscript in the late 1500s, still in what was now Istanbul, a century after the fall of the city, was acquired by Moses Hamon, the Arabic-speaking Jewish physician to sultan Suleiman I, also known as the Magnificent, famed ruler of the Ottoman Empire, and Moses Hamon or his son may have added the Hebrew names of the plants to the manuscript (seen by the root in the plant image above). The work also records plant names in Thracian, ancient Egyptian, North African (Carthaginian or Punic) and other languages, names in languages which would have been lost to us were it not for this manuscript. And finally, in 1569 Emperor Maximilian II of the Habsburgs acquired the codex for the imperial library in Vienna, later the Austrian National Library, hence the name Codex Vindobonensis.

The front matter consists of a series of miniature paintings, the first being this remarkable image of a peacock (above). It is curious that it is a frontispiece of a book on herbal medicine rather than part of the ornithological treatise that we saw contained in the latter part of the manuscript, so maybe when the codex was rebound, a mistake could have been made? Another explanation can perhaps be found in the decoration of the Church of Saint Polyeuctus which Juliana Anicia had financed, featuring peacocks in this kind of pose, frontal and with the feathers spread out. It was the symbolic bird of an empress, and also of the goddess Juno or Hera. In Ancient Greece it was a symbol of immortality, symbolism which was adopted by the early Christian church, so the peacock illustration may in fact be a Christian symbol of immortality, perhaps a reference to a prophesized immortality for the manuscript or even a symbol of Juliana or her aspirations or the aspirations of others for her? In 512, in fact, there was a power struggle and Juliana’s husband was approached by one faction to become emperor, which he declined, so there was much political turmoil in Constantinople at the exact time of the creation of the codex, a fact which may be significant for the interpretation of the role of Anicia Juliana in this codex and in Constantinople at that time.

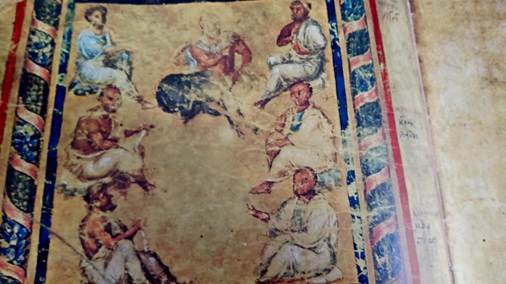

This miniature (above) on folio 3v depicts 7 physicians. They had to be 7 as it was a sacred number like in the 7 sages, among whom is the famous Galen of Pergamum (2nd c.) in the center, i.e., a hundred years after Dioscorides. In his works, Galen makes frequent references to De Materia Medica. He is flanked by Crateuas (ca. 2nd c. BCE), and Dioscorides himself, which may convey the influence on Galen of both Crateuas and Dioscorides. It is the earliest known miniature painting to use a solid gold-leaf background, which of course came to characterize religious Byzantine art, from household icons to mosaics adorning churches.

In another miniature on folio 2v (above) featuring doctors or authors of medical texts we see the centaur Cheiron in the center, whom the natural historian Pliny the Elder credited with discovering botany and pharmacology, the science of herbs, and medicine. One could probably speculate about Cheiron being juxtaposed to Galen in the center, old medicine versus new perhaps?

Another interesting miniature on folio 4v (above) depicts the author seated opposite Heuresis, personification of Discovery or Invention, as in Heureka (Eureka!), holding a mandrake, of Harry Potter fame, presumably giving it to humans represented by Dioscorides himself, depicted almost as pivotal as the gift of fire given by Prometheus to the human race, maybe even a veiled reference to the “Prometheus herb,” φάρμακον Προμήθειον, referencing most likely the mandrake, in Apollonius Rhodius’ epic Argonautica, but also speaking to its significance as something of a panacea, able to cure everything from asthma, to toothache to depression and even leprosy. It was also used as an anesthetic in surgery, which no doubt Dioscorides himself would have employed as an army doctor. Dioscorides prescribes mixing the juice from the mandrake root with wine and vinegar to put patients to sleep before surgery.

But because of its supposed human-like form and its narcotic properties, it also had magical dimensions. At the bottom of the image lies a dog killed by what was later thought to be the lethal scream of the mandrake when uprooted. The use of a dog is first attested in western literature in Roman-Jewish historian Josephus in the 1st c., a contemporary of Dioscorides, but he does not mention a scream, which seems to be a medieval addition. In his work Jewish War, Josephus writes the following regarding the mandrake:

“…flame-colored and towards evening emitting a brilliant light [most likely another superstitious element], it eludes the grasp of people who approach with the intention of plucking it, as it shrinks up and can only be made to stand still by pouring upon it certain secretions of the human body. Yet even then to touch it, is fatal…a mode of capturing it, is as follows. They dig all around it, leaving but a minute portion of the root covered; they then tie a dog to it, and the animal rushing to follow the person who tied him, easily pulls it up but instantly dies…” (Joseph. BJ 7.6.3).

This painting on folio 5v (above) also speaks to the prominent role of the mandrake in this manuscript in which a personification of Γνῶσις, Knowledge, holds out the mandrake for an artist to copy while Dioscorides writes in a codex, so maybe this scene depicts the creation of our codex and if so, it may demonstrate that some of the plants were painted from actual real-life samples?

Also included in the exhibit is a 1549 edition from Lyon of Greek physician Galen’s (129-ca. 216 CE) De compositione pharmacorum localium libri decem by Janus Cornarius (1500-1555). Galen’s writings on botanical pharmacology owes much to Dioscorides and Galen frequently cites him.

Ptolemy’s Geography

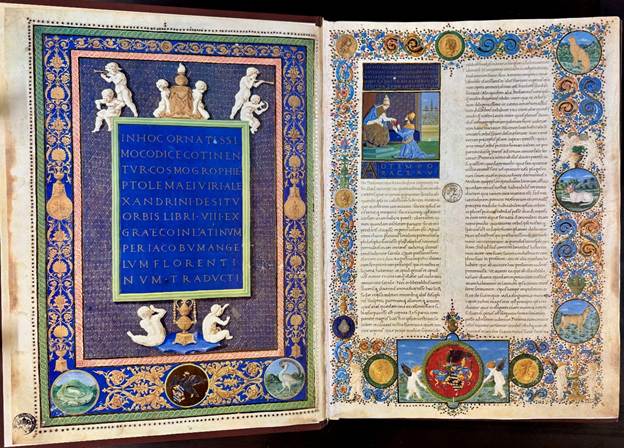

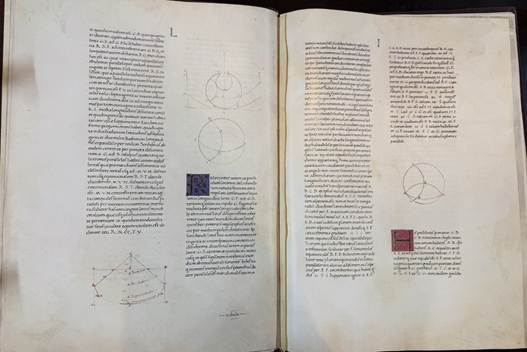

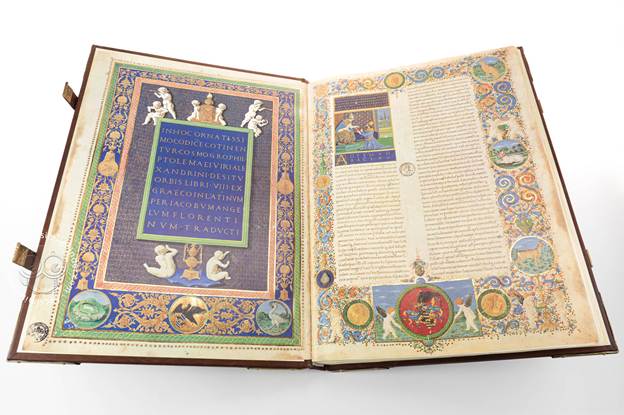

This manuscript facsimile features the first Latin translation from Greek of Ptolemy’s Geography (Γεωγραφικὴ Ὑφήγησις, geographical guide, Geographia Claudii Ptolemaei) undertaken by Jacopo di Angelo (Iacobus Angelus) from Scarperia, a small town just north of Florence, in 1409, published in this manuscript from 1472. Jacopo di Angelo gave the work the title Cosmographia to capture its use of astronomy (law of stars), going beyond simply describing Earth, geography. The maps were translated by Francesco di Lapacino and Domenico di Leonardo Boninsegni. The copyist is listed on folio 70 recto as Frenchman Hugues Commineau (Ital. Ugo Comminelli).

Many text pages are elaborately adorned with colorful and golden vignettes and border decorations. The manuscript illuminations are by well-known miniature painters and engravers, chiefly Francesco Rosselli and Pietro del Massaio (the illustrator of the maps). The manuscript was owned (possibly also commissioned) by Federico da Montefeltro, Duke of Urbino, seen below in a famous painting by Piero della Francesca.

The original (Codex Urb. Lat. 277) is in the Biblioteca Apostolica Vaticana (earlier in the Duke’s library in Urbino). Di Angelo studied Greek under humanist scholar Manuel Chrysoloras in Venice and Constantinople, the author of a manuscript recently on display at Dumbarton Oaks.

Iacobus Angelus in his studio in a vignette on folio 3 recto.

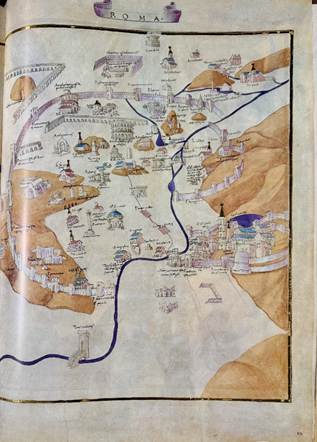

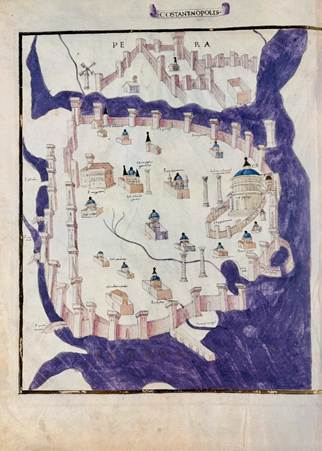

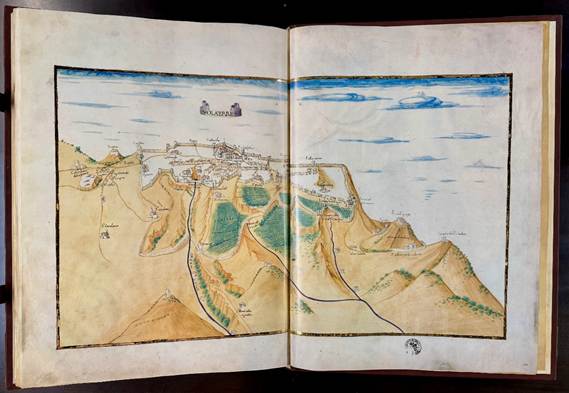

The codex in eight books, based on the number of papyrus rolls Ptolemy used, contains 44 maps of Europe, Asia, and Africa and a world map of 26 countries, as well as maps of major cities like Rome, Constantinople, Damascus, Jerusalem, Alexandria, Venice, Milan, Florence, and Volterra (the rather modest town had lost a battle to Montefeltro, thus its inclusion could be explained as an homage to the Duke or perhaps proscribed by him).

Florence with the Baptistery and Palazzo Vecchio and Piazza della Signoria, Palazzo Pitti, the Church of San Miniato, il Bargello, Orsanmichele, Santa Croce and San Lorenzo, Ponte Vecchio and the river Arno in the 1400s.

Rome with the Colosseum, Saint Peter’s, Castel Sant’Angelo, Tiber Island, the columns of Trajan and Marcus Aurelius, the Pantheon, Campidoglio, the Baths of Diocletian in the 1400s.

Constantinople with the Hippodrome and Hagia Sophia and the Byzantine wall and the ports in the 1400s.

Volterra with Palazzo del Capitano, Palazzo del Podestà, the Church of San Michele, the Cathedral of San Giovanni in the 1400s.

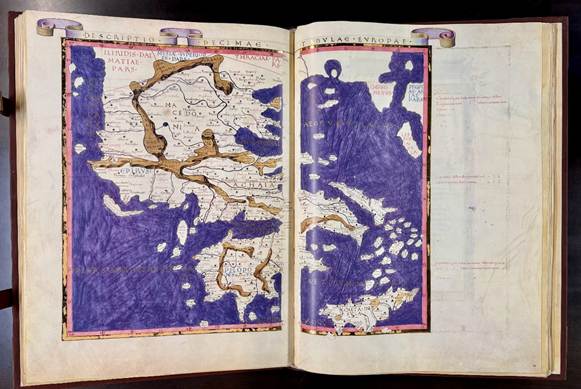

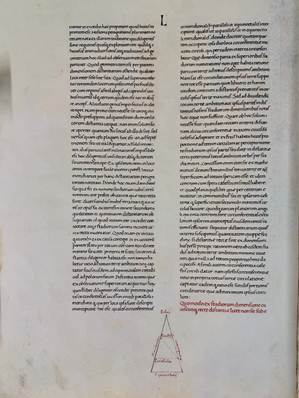

The first book (liber primvs) begins on fol. 3r and is a cartographic treatise describing Ptolemy’s methods; the second book (liber secvndvs, foll. 13r-24v) contains calculations and descriptions pertaining to Britannia, Hispania, Germania, Gallia, Dalmatia; the third Italy and Greece (foll. 24v-36r); the fourth Mauretania, Numidia, Ethiopia, Libya, Egypt, nothing about sub-Saharan Africa (foll. 36r-44r); the fifth pertains to Syria, Palestine, Mesopotamia, Babylonia, Pontus, Iberia, Albania, Cyprus, Lycia, Armenia, and Cappadocia (foll. 44v-55r); the sixth to Assyria, Parthia, Persis, Scythia (foll. 55v-62r); the seventh book to India and Taprobane (foll. 62v-66v), and instructions on how to construct a world map.

Greece with its mainland, Achaia, Macedonia, the Peloponnese, Corinth, Sparta, Athens, and Piraeus, many of its islands (Corfù, Paros, Melos, Delos, Lesbos, Lemnos, Naxos, Euboea, Mykonos, Mount Athos, etc.), and Crete surrounded by the Adriatic, Ionian, and Aegean sees.

Ptolemy, Πτολεμαῖος, a Greek from Egypt, wrote his atlas and gazetteer around 150 BCE. It is believed to have been based on a now lost atlas by Marinus of Tyre (ca. 70-130 CE), which Ptolemy also acknowledges, and other predecessors. Maps using scientific principles and mathematical and astronomical calculations had been produced at least since the time of another Greek astronomer, Eratosthenes (ca. 276–ca.195 BCE).

The translation of the Geography into Arabic in the 9th century held much influence on the Islamic world just like the Latin translation by Jacopo di Angelo on the European renaissance and humanism. Florentine Poggio Bracciolini relates a story that when he visited his friend Niccolò Niccoli (a man who boasted the possession of ca. 800 manuscripts which subsequently came to form the library of Cosimo de’ Medici at San Marco) that he had found him in the company of Cosimo de’ Medici and Enea Silvio Bartolomeo Piccolomini (Pope Pius II) discussing Ptolemy’s Geography. Ptolemy’s text had been discovered in the west not many years earlier after having been thought lost for almost a thousand years although it had been translated into Arabic, so Islamic scholars were aware of its existence. Several Greek and Arabic manuscripts have been preserved either in full or in part going back to the twelfth and thirteenth centuries.

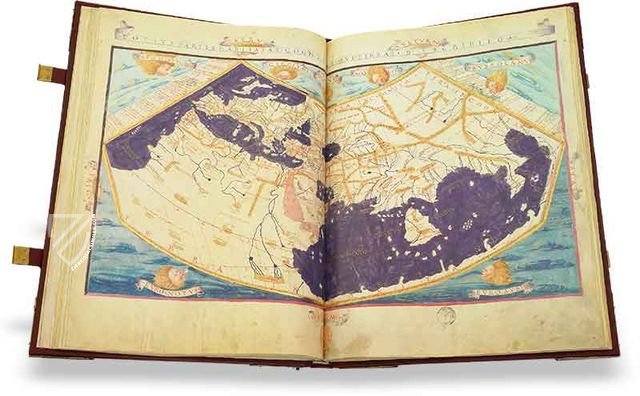

Ptolemy’s inhabited world, oikoumenē, spanned 180 degrees longitude from the Canary (Blessed) Islands in the Atlantic Ocean, according to the world map, to central China and about 80 degrees latitude from the Shetland Islands to the east coast of Africa; however, in the text part the longitudinal calculations using time seem to refer to measurements with Alexandria as the point of reference. Ptolemy also points out that he does not include all place names, only important rivers, cities, etc., although many smaller towns are also included in individual maps in what may be later additions. Ptolemy remarks that the world should be represented on a globe rather than on a two-dimensional map but that details would be difficult to represent on a globe. He further writes that it is not enough to know the distance between two locations but one must also calculate the distances and relationships of them with respect to cardinal points, i.e., the equator and the poles, and the circumference of the earth, the movement of the earth, and the passage of time, using Midsummer Day (the longest day) as reference (fol. 4r).

Ptolemy realized that he did not include the entire world. The words “terra incognita” occur at the edges of the world map, which comprises Europe minus most of Scandinavia, Africa minus areas south of Ethiopia, and much of Asia as far east as China, so not Japan, with a few erroneous representations. America and Australia were unknown to Ptolemy in the 2nd century although Christopher Columbus “discovered” America only twenty years after the creation of the renaissance manuscript using among other sources Ptolemy’s calculations when sailing to the new world. However, it was inaccurate longitudinal calculations chiefly in Ptolemy which led Columbus and others to believe that the distances were much shorter, especially between Europe and Asia, than they actually were.

In his Geography, and in many of his other works, especially the so called Almagest, Ptolemy argued for a geocentric understanding of the universe although he viewed planet Earth as spherical without knowledge of the laws of gravity. The Ptolemaic system was based on insights going back to Greeks like Aristotle, fourth century BCE, and Hipparchus, second century BCE, who in turn had been influenced by Babylonian astronomers. Ptolemy erroneously argued that the heavenly bodies’ circular motions were caused by their being attached to invisible revolving solid spheres with no empty spaces enclosed one inside the other. Based on this theory he described the motions of and calculated the distances to the Sun, the Moon, and to other planets and stars. It should also be said that several of the complex latitudinal calculations in the Geography are quite accurate. The Ptolemaic geocentric system was the official theory of the universe for more than 1,500 until the Copernican heliocentric system replaced it.

The first part of the manuscript contains a discussion of the data and methods Ptolemy used. He notes the importance of astronomical calculations rather than relying on sailors’ or travelers’ accounts although it is generally believed that he gained much information also from such sources. Alexandria, Ptolemy’s hometown, with its great library and lighthouse was perfectly positioned for reports of this kind with traders assembling from the Nile, India, Malaysia, Arabia, China, and elsewhere. In the second part of the book, Ptolemy provides a catalogue of 8,000 place names (towns, rivers, seas, lakes, mountains, etc.), the largest such list from antiquity. More than 6,000 of these have assigned coordinates so that they can be placed into a grid spanning the globe (see the world map below).

The maps begin with book eight. Although many of the maps are later additions, the world map (mappa mundi) may be by Ptolemy himself who based his map-making largely on longitude and latitude coordinates, which he or Marinus of Tyre is credited with introducing, for all the geographic areas contained in the manuscript, laying the foundation for modern cartography.

Ptolemy’s maps, which were issued in several printed and vernacular editions as well, were not replaced until 1570 with the publication of Theatrum Orbis Terrarum by Flemish geographer Abraham Ortelius. In the late 1800s another important cartographic project was undertaken, Heinrich Kiepert’s Formae Orbis Antiqui, owned by the CHS, expanded from his Atlas antiquus: Zwölf Karten zur alten Geschichte. Due to Kiepert’s untimely death in 1899, he was unfortunately barely able to complete the first of 36 planned engraved maps with a Preface, Asia provincial, Insulae maris Aegaei, Graecia septentrionalis, Illyricum et Thraecia, and Insulae Britannicae. One of the maps, “Orbis terrarum secundum Cl. Ptolemaeum” was completed in 1911 by his son Richard who continued his father’s work and was able to complete many more maps, but when he also passed in 1915, the project was still shy of eleven maps in addition to a planned gazetteer. Then the world wars put a stop to any further work on this monumental task. Another interesting work from the late 1800s, also owned by the CHS, is Adolf Erik Nordenskjöld’s Periplus: An essay on the early history of charts and sailing-directions of which there are many ancient Greek predecessors such as peripli by Nearchus, Scymnus of Chios, Scylax of Caryanda, Himilco the Navigator, Hanno the Navigator, and others who charted landmarks along the coastlines of the world for navigational guidance. Herodotus and Thucydides, Hecataeus of Miletus, Diodorus Siculus, Pausanias, Pliny the Elder, and Strabo, all used peripli in their work. Nordenskjöld’s periplus also offers a nice overview of Greek cartography before Ptolemy and the history of peripli in antiquity and of portolan charts in the middle ages.

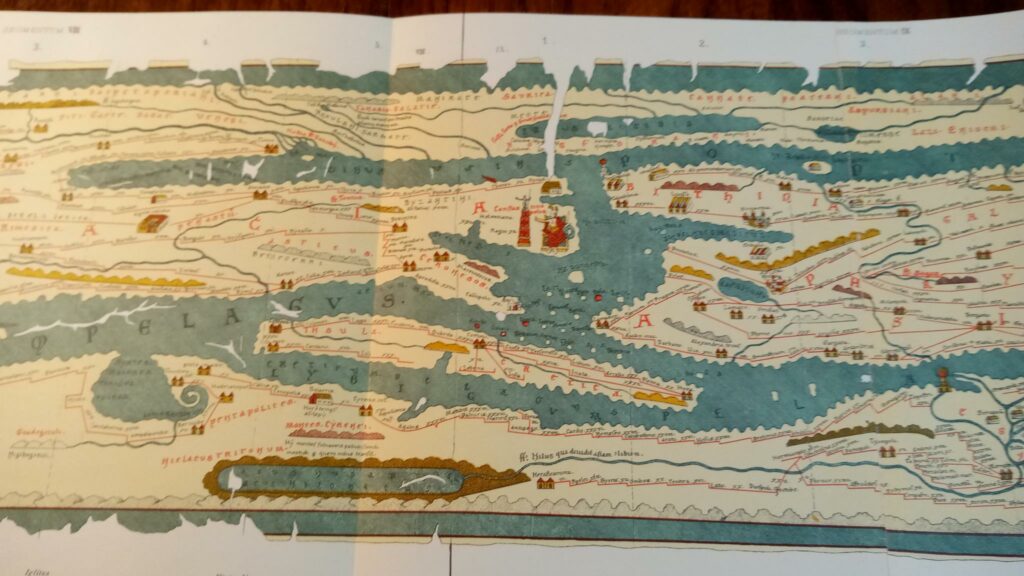

The world in the 2nd century CE, foll. 72v-73r.

Some items of note in Ptolemy’s Geography include the large size of Sri Lanka in contrast to India (see the island featured in the lower right in the image above. In antiquity it was called Taprobane and was a source of gems in the Roman world), and the extension of China too far south, in fact, nearly connecting China with Africa, and the erroneously enclosed, landlocked sea between Africa and Asia, i.e., the Indian Ocean, and the dedication on the frontispiece to Pope Alexander the Third and an illumination representing Iacobus Angelus giving his translation to this Pope. Alexander the III was Pope in the 1100s, not in the 1400s when Jacopo di Angelo translated the work into Latin. The Pope in 1409 was a so-called anti-Pope, Alexander the Fifth, so either this is a mistake or a deliberate act of damnatio memoriae —

“Iacopi [sic] Angeli Florentini praefatio in Cosmographiam Ptolemaei Alexandrini ex Graeco in Latinvm traducta ad Alexandrvm Tertivm svmmvm pontificem.”

“The Florentine Iacobus Angelus’ preface to Ptolemy of Alexandria’s Cosmography translated into Latin for Pope Alexander the Third.”

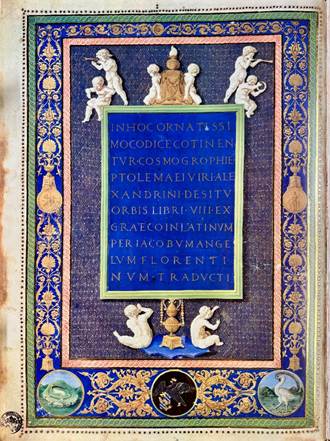

The frontispiece contains the usual menagerie of plants and animals (deer, leopard, dog, some imaginary or now extinct(?) animals), and arabesques with candelabras and vases in a manuscript from the renaissance, as also the obligatory putti or cherubs sounding trumpets and tambourines and triangles and bells, one putto is urinating, another popular motif during the renaissance, and the coat of arms of Montefeltro (Duke of Urbino). There are further medallions of Roman emperors Claudius, Trajan, and Augustus, depictions of Roman emperors being typical for the renaissance. The text on the title page reads:

“In hoc ornatissimo codice continentvr Cosmographie Ptolemaei viri Alexandrini situ orbis libri VIII ex Graeco in Latinvm per Iacobvm Angelvm Florentinvm traducti”

(note mistakes made: “cotinentvr” instead of continentvr and “Cosmogrophie” instead of Cosmographie, probably made by the artists rather than the copyists).

“In this splendid book is contained Cosmography by Ptolemy, a man from Alexandria, about the world in eight books translated from Greek into Latin by Iacobus Angelus, the Florentine.”

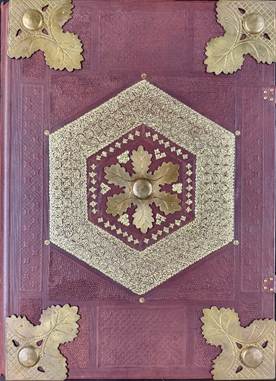

CHS’s facsimile was produced in 1982 by the Belser Verlag, Zürich. It is very large (59.3 × 43.5 cm, 135 folios, 270 pages) and one of the most beautiful manuscripts ever made, faithfully reflected in the CHS facsimile. The Vatican Library has digitized the codex, but the quality is rather poor.

A possible predecessor to Ptolemy’s Geographia is the Peutinger map (Peutinger Table, Tabula Peutingeriana) mapping the road network of the Roman Empire to facilitate trade and conquest. The preserved map dates to ca. 1200, but the original most likely to late antiquity (5th century) copied after an even older map prepared by Agrippa, the general and son-in-law of emperor Augustus who among other accomplishments commissioned the construction of the famous Pantheon in Rome. The Roman Empire was vast, so the map covers more or less the same areas as Ptolemy’s although in a west to east direction, Europe (although a piece of the original scroll covering the Iberian Peninsula and the British Isles has been lost), North Africa, and parts of Asia with India (not a Roman province), though not China.

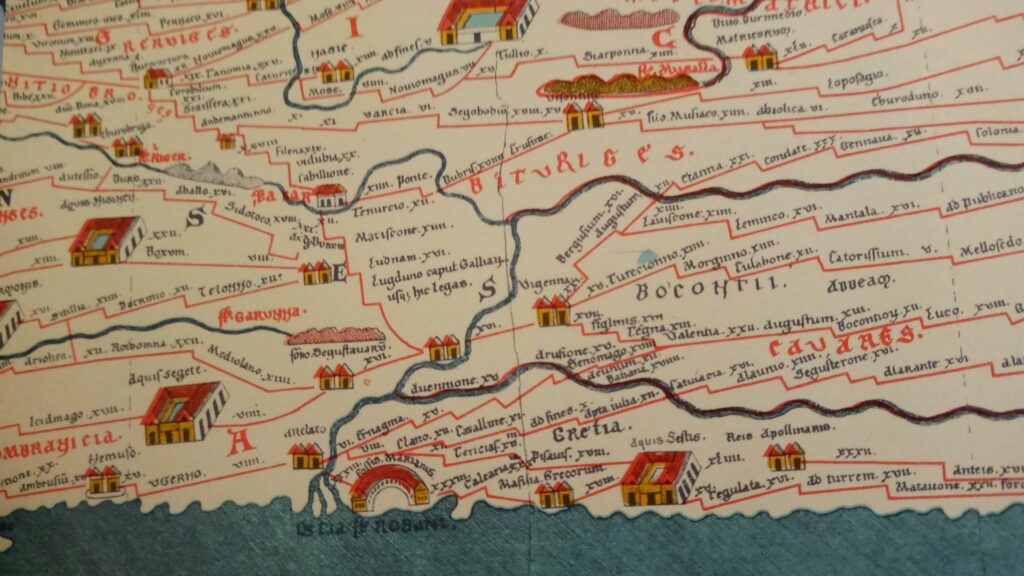

Francia, Lugdunum, present-day Lyon.

The map is named after Konrad Peutinger, a 16th century German antiquarian art and book collector. The original copy from 1200 is presently housed in the Austrian National Library in Vienna (Codex Vindobonensis 324). The date of the late antique original is not precise but there are some clues such as Constantinople which was founded in 328. The map also mentions Francia, which came into existence as a state in the 5th century (see image above).

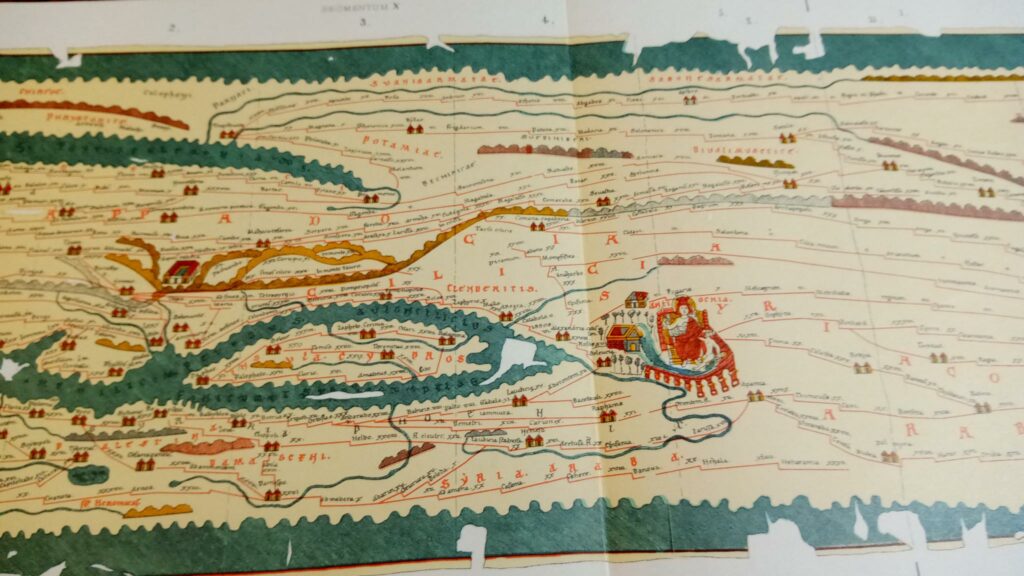

The map consists of a scroll measuring more than 6 meters made up of 11 sections (see image below). Thousands of place names are indicated with Rome, Constantinople, and Antioch receiving special illustrative attention (see below).

The CHS copy measures the entire length of the large table in the Mosaic Room.

Constantinople, capital of eastern Rome, present-day Istanbul, Turkey.

Syria, Antioch.

If your curiosity has been piqued and you wish to learn more about ancient medicinal plants or about the unique Vienna Dioscorides manuscript, with so many firsts, the first dedication portrait, the first gold-leaf background which came to characterize Byzantine art, the first ornithological treatise, names of plants which would not have come down to us were it not for this manuscript, and the intriguing and enigmatic role of a female patron of the arts some 1,500 years ago, or if you wish to learn about mapping the known world of the 2nd c. CE Roman Empire and view a detailed depiction of the world as it was known then, or learn about the latitude and longitude coordinates, some accurate and some inaccurate, for thousands of sites in Europe, Africa, and Asia, or simply admire the gold-leaf opulence of a manuscript from the Italian renaissance, CHS researchers can save a trip to Vienna and the Vatican and view these exquisite manuscript facsimiles in person. To learn about CHS events open to the public or to apply for CHS library access for scholars researching ancient Greece, consult the CHS website and social media posts.