Basel

[This article was originally published in German as “Räume im Anderen und der griechische Liebesroman des Xenophon von Ephesos. Träume?” in A. Loprieno (ed.), Mensch und Raum von der Antike bis zur Gegenwart, Munich and Leipzig: Saur 2006 (Colloquium Rauricum 9) 71–103 (with 2 further attachments at the end of the volume).]

I. Space and the Novel [1]

1§1. In the present debate of cultural and literary studies space is on the agenda. [2] Next to time, space determines the thoughts as well as the being of those acting in it. The notion of space is variably applicable to diverse contexts of everyday life, and differently used in cultural discourses, as for example in science, art, and religion. [3] In an effort to define space the following categorization emerges: (a) the expanse of the earth as landscape, (b) a given “thing”, a priori of our perception, and (c) the category of coexistence in logical thought. In addition the notion “space” is usually differentiated from “place”. Place represents a physical, local and specific spot in a relational perspective, while space is defined as “a fundamental system of reference or the total sum of all places.” [4] There is space as an abstract container for something in the Aristotelean and Euclidean tradition, primarily in a purely physical representation of knowledge. In everyday life and human perspective, however, space is differentiated in numerous forms according to context and because of its temporal definiteness. When the temporal entwines with space, space becomes conceivable only as a difference of experience between living things, or objects, and framing spatiality. Once in contact with space, energy is released on any point of the temporal axis either in a performative action or in the all-embracing view. And the observer is drawn into the power of this energy. In contrast to the philosophically and physically abstract idea, there is thus the fictional, poetic space in the area of artificial mimesis, concretized in countless spaces that determine the respective work as well as its reception. [5]

1§2. Therefore literary texts are also based on specific chronotopical perceptions that are caused by both a historical and pragmatic contemporary world and a context of genre. Literature therefore works on the epistemological and ontological worldview of a certain age. However, it does not have to be an exact mirror-image of that world. Due to generic conventions and norms, these basic models are blurred, especially in fictional texts. Here in its temporal dimension as a space-and-time the constitutive imaginary space becomes hybridized, pluralized, and contextualized.

1§3. In Classical philology the cultural question of space has not been dealt with systematically enough. In Greek literature in particular there are only a few important reflections on this topic, reduced to Homer, Herodotus, and drama. [6] The theoretical insight in this subject is most advanced in the field of the love novel. Here, research conducted in the past thirty-five years has shown that these fictional prose works are not so trivial and mediocre as was once thought. [7] A late rehabilitation has followed earlier critisism. The plot of the ideal love novel looks as follows: Two young people of marriageable age, from good families and of exceptional beauty fall in love with each other at first sight. Their excessive passion turns out to be a sickness. They swear eternal fidelity and chastity to each other and soon marry—or they reach this goal at the end, since unsolvable problems delay the marriage. They are suddenly separated by destiny, and the young man sets off in search of the lost girl. Carried off by pirates and robbers, they survive countless vicissitudes, such as seizure by pirates, being thrown in jail, being shipwrecked, being sold into slavery and even apparent death (Scheintod). In all of these instances their loyalty is tested by numerous proposals from a third party. Body and mind of both protagonists are threatened with countless violations and false accusations, until at last the couple find each other again in a happy end.

1§4. For this type of novel the Russian formalist and classicist Michail Bakhtin (1895-1975) has developed the theory on the so-called ‘chronotope’, that is, on the experience of time and space. [8] It originates in the 1930s, therefore to some extent showing the prejudice of the time against the literary genre, but it first became known in the West only in the early 1970s. Bakhtin believes that the primary dimension of the novel is space, whereas the temporal axis moves almost against the zero-point. The adventure time that perpetuates itself in the plot has very little effect on history or processes drawn from everday life, least of all on the biological time of the heroes, who do not undergo any kind of maturation or mental development in the novel. The time of the episodes is broken into snapshots and finds its counterpart in the wide extension of space of almost the entire Mediterranean world. Due to the missing temporal relation, these places lack historical setting and actualization. Thus the wide space proves to be a rather peculiar form of abstraction. [9]

1§5. The chiefly right observations of Bakhtin have been recently subjected to criticism and acquired further specifications. [10] David Konstan has stressed that time is also essential for the character development of the typical sexual symmetry between both heroes. [11] Further it is just space that is necessary for the creation of separate and independent spheres in a plot based on mutual love. [12] The debate was definitely deepened by a colloquium held in 2001 in Crete, the proceedings of which are now published. [13] As stated in several new contributions, space is not as abstract as Bakhtin suggested, but rather the contemporary world of imperial Rome entering the texts also to some degree. [14] In what follows I am not particularly concerned with the influence of contemporary history, and even less with a politically correct emphasis on the equal worth of the sexes. Rather, I want to pinpoint love as a phenomenon that is constitutive for the genre as it relates to space.

1§6. In a recent article on Chariton I summarized the relation between Greek novel and love according to Roland Barthes and Anne Carson as follows: [15]

In the Greek conception Eros … has something to do with lacking. We never love what we can easily have, but yearn for what is gotten only with difficulty. Thus an important love always implies—to speak in the words of Roland Barthes—a discourse of absence: [16] there is a gap separating subject from object.

According to Aristotle, longing is the desire (ὄρεξις) for the beautiful and pleasant. Everyone who yearns after it does this in his imagination (φαντασία). We use our memory or imagine things in the future closing the gap and granting the wish (Rhetoric 1.11, 1370a14–1370b29). Whoever loves, struggles for fulfillment but suffers until it is reached. The lover transfers his condition, so defined, into speech and eventually also into writing.

Anne Carson has shown these contexts in a monograph on Sappho. [17] From this basis she arrives at the thesis that the novel pursues in extenso the lyrical strategy of triangulation which expresses the gap of love. The authors of novels make use of this erotic situation from lyric and extend them to a longer narrative syntagma in the phantasy. In their fictional prose texts they work in a way of a chain technique applying repetitions and variations which are brought forward by the tropology of metaphor and metonymy. [18]

1§7. I contend that the feeling of a gap externalizes and affirms itself in space. The lovers long for one another, while the threats and instances of violence from a third person manifest themselves in a spatial separation full of events. Therefore the adventures of the Greek novel which happen in the extended space are neither an addition nor a means providing a primarily boring genre with action, but they are constitutive for the discourse of “triangulation” of love. Wandering, pursuit, and searching for the other in the wide intermediate space of the Mediterranean are necessary to guarantee the extension of the fictional story. Space thus relates to love and narration. It is in a sense the plain where the erotic plot is projected and acted out. Without spatial separation there can be no story of trials by outsiders or the search driven by desire. Notorious robbers and pirates embody the privative through which the lack is perpetuated. On the other hand, space needs a longing for an object in order to be opened. [19] The arousal of interest in the love novel naturally results in the action of falling in love, while in further novel-like textual productions, i.e. the so-called fringe novels, such a πόθος can also be presented as curiosity, lust after knowledge, justice, piety, or mystery-like knowledge. [20] (See appendices 2 and 3.)

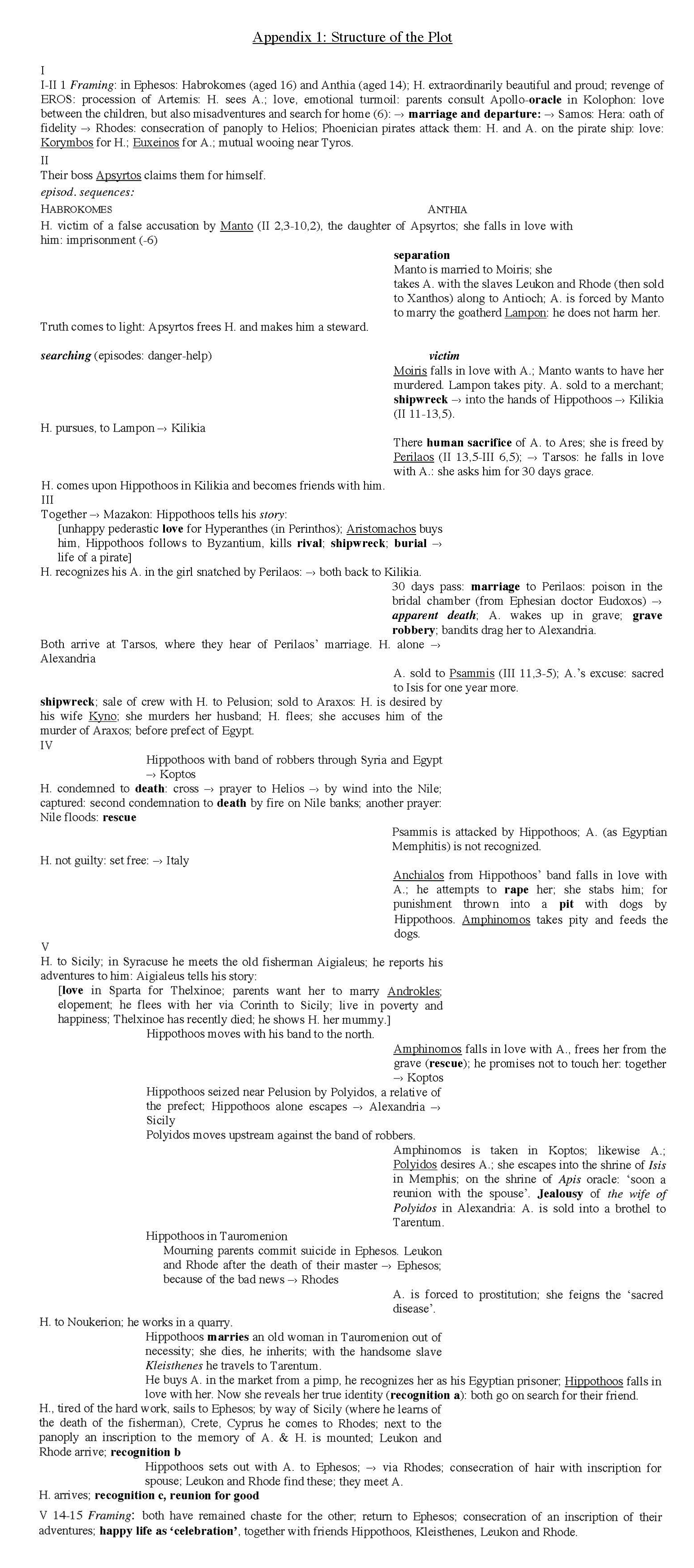

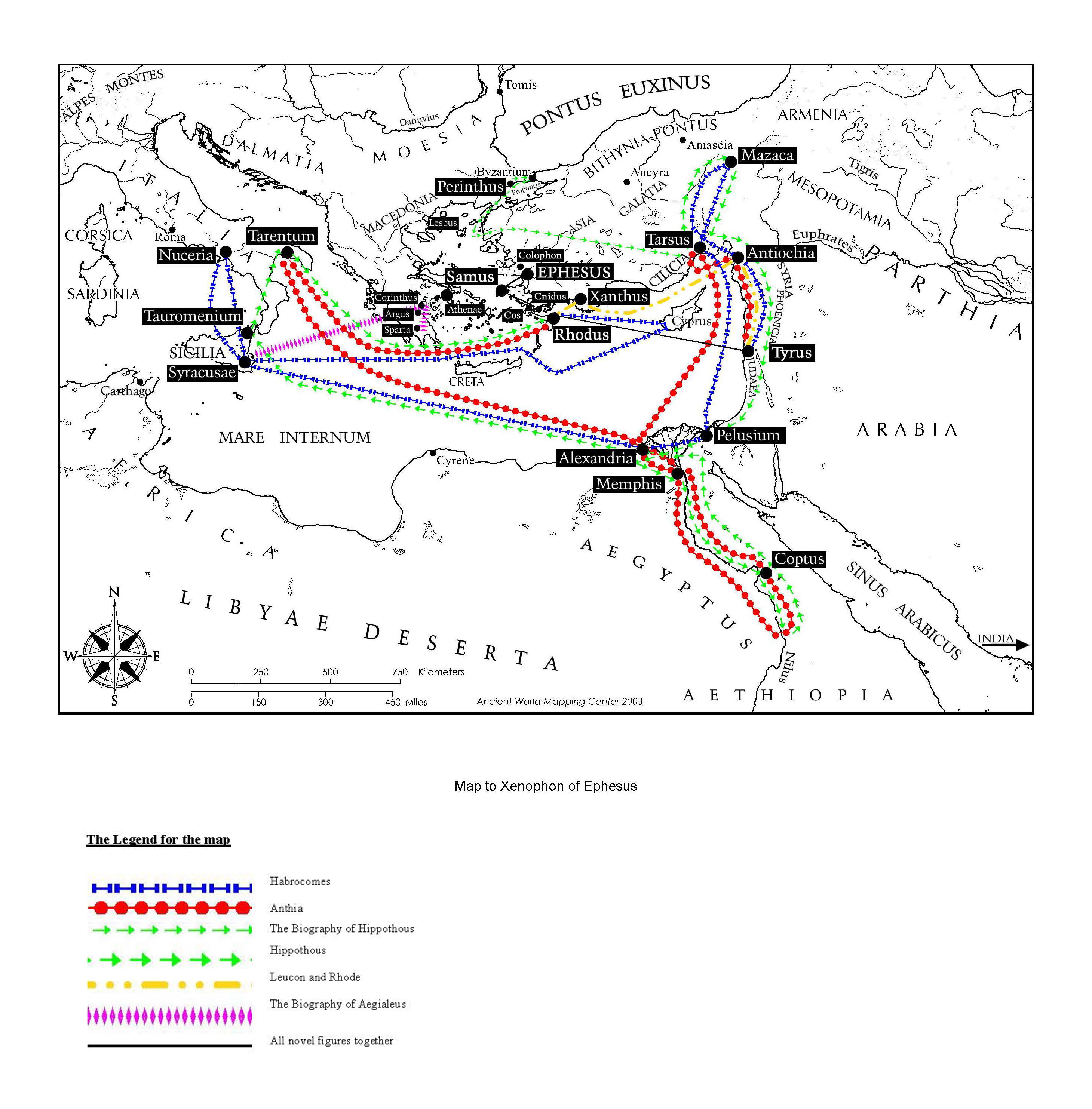

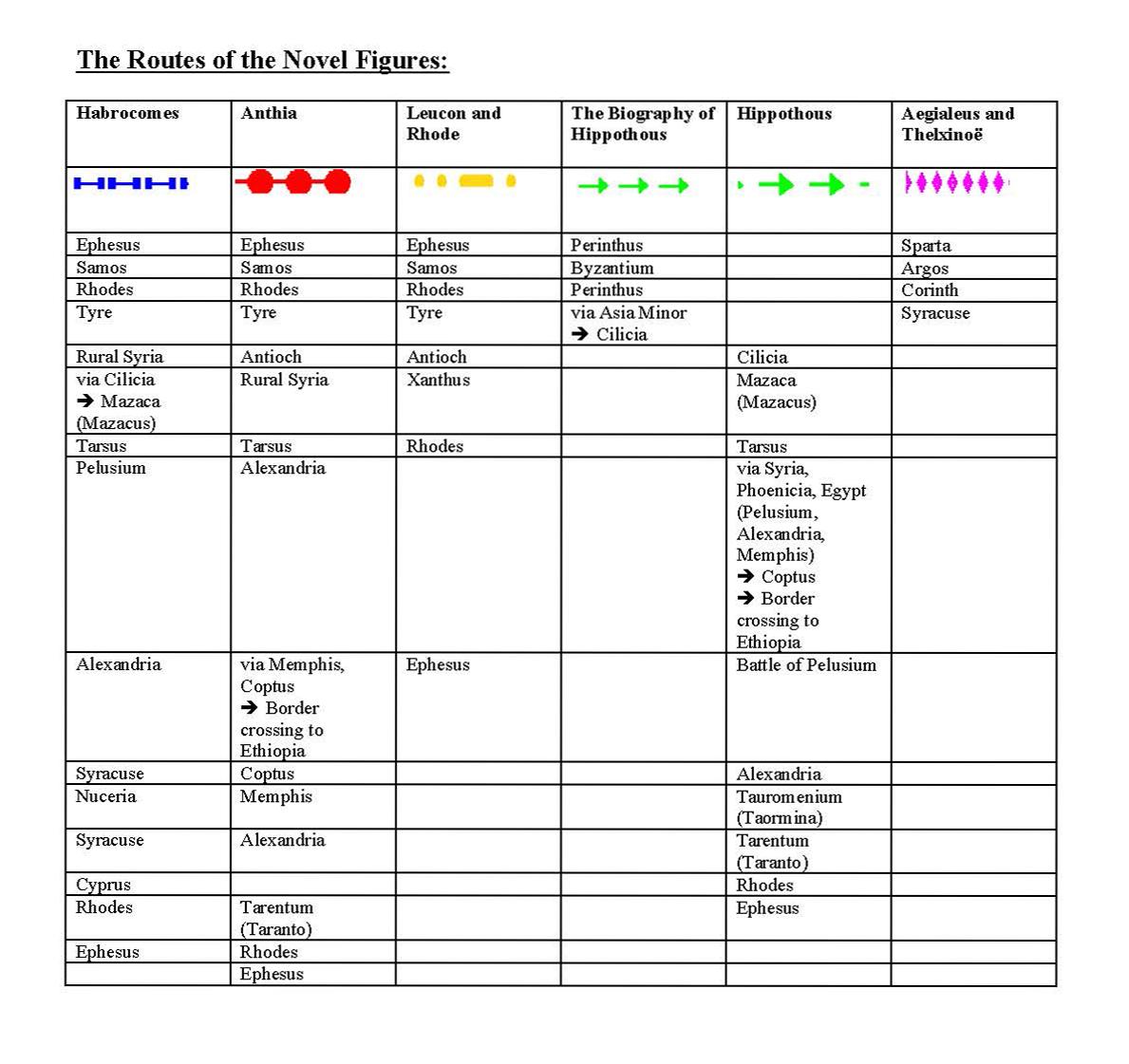

1§8. Linking the episode-like temporal enclaves to changing locales extends the plot in conformity with chance. But ordering the place one after another also yields important routes loaded with suggestive meaning. Simultaneously the selection of countries and places reflects the worldview and political conditions of historical developments. The type of Greek love novel is ultimately a part of the growing movement of the Second Sophistic in the cities of Asia Minor. The literary production that is orientated on classical times and intertextually refers to the classical literature, is a part of the strategy of cultural self assertion by the Greeks against the political dominance of the Romans in earlier and middle imperial times. Characteristically, not only Rome and Athens are considerably neglected, but also the Greek mainland. Heroes move frequently from Asia Minor east to Phoenicia, Kilikia and Mesopotamia. Egypt plays also an important role as a spiritual landscape; [21] moreover, the wanderings often lead to Sicily and Southern Italy. [22] The novel reflects the enlargement of space through Alexander the Great and the sensation of the Hellenistic individual to be cast and lost in these new worlds. [23] Seen in different perspectives, the sudden lack of orientation was used for a religious, psychological, and sociological explanation of the rise of the genre. [24] The liminal places are hardly specified. Only small tufts of information give them a concrete appearance. Of course, they are not represented as regions of the wholly Other, where experiences with the foreign could deepen the puppet-like figures in the sense of a maturation. Rather, the plot concerns only the scenes of action on the border with the Other, where trouble always runs by the same kinds. Meaning that lies behind the route is not actually established, but only simulated.

II. Xenophon of Ephesos

2§1. While Bakhtin illustrated his theory by means of Achilleus Tatios, I would like to establish the problematic and set out my thoughts on the function of space in Xenophon’s Ephesiaka. This novel is especially well suited for this purpose, since the representation of space is here particularly complex through numerous episodes and scene changes. The heroes act in a nearly unlimited area and the more or less random incidents happen in a time that passes without leaving a genuine trace on them. The spatial dimension seems considerably hazy. Apart from a few familiar precise statements connected to Xenophon’s hometown, Ephesos, and the Nile delta, we find hardly any true details concerning the localization. [25] Everything gives a haphazardly assembled impression and the measurements of distance on the Asia Minor coast seem to be taken partly from Herodotus and geographical handbooks. [26] Moreover, the fictional narration—in contrast to Chariton—is not any more precisely anchored in the classical time. One feels transferred to an almost timeless world, that makes it particularly difficult to date the piece. Nowadays it is generally assumed that Xenophon wrote his work after Chariton in the reign of Hadrian (117–138 AD) or Antoninus Pius (136–161 AD). [27]

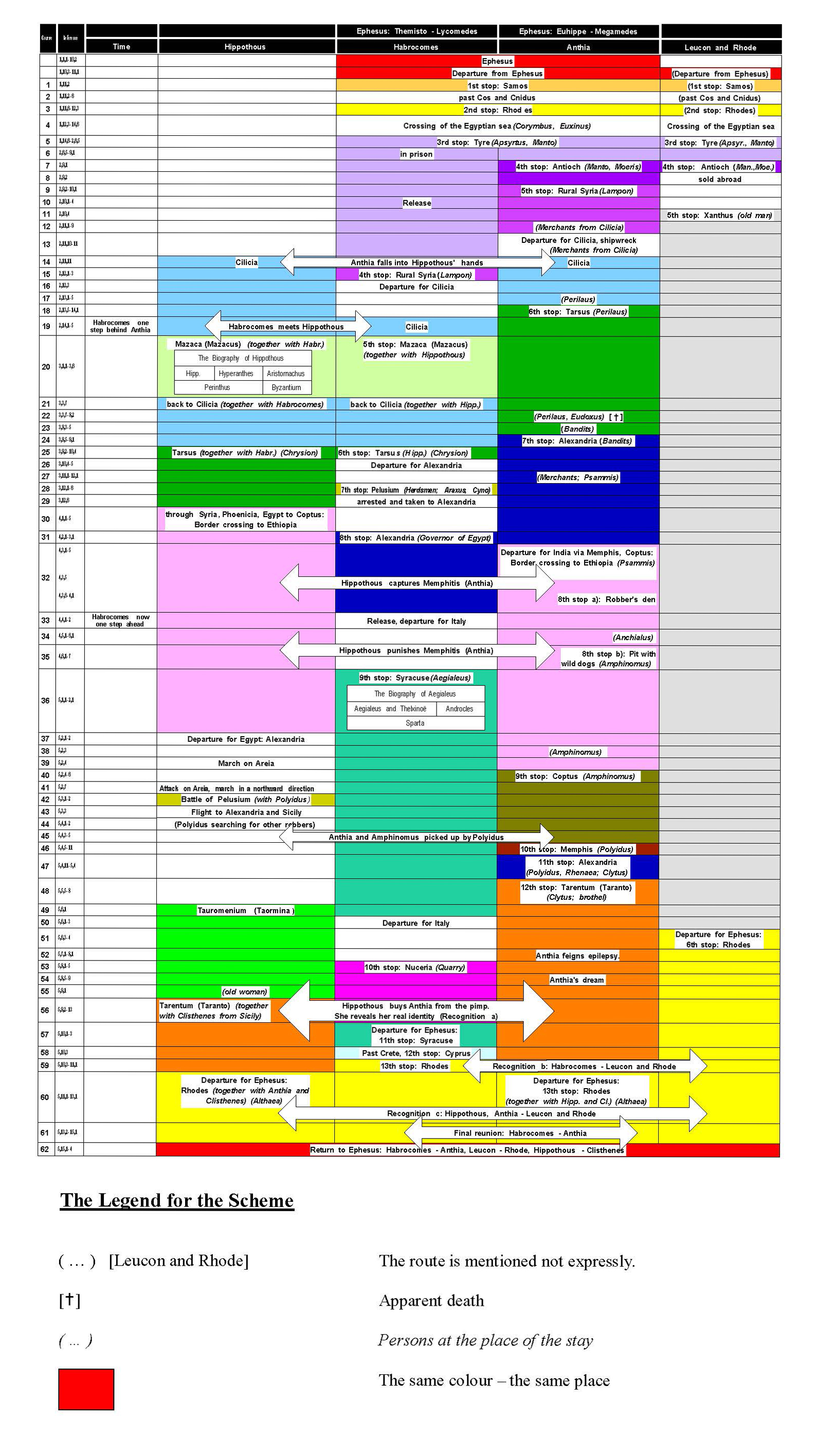

2§2. The effect of the wave of adventures on the modern reader is somewhat tiring. Usually a harsh judgment would be passed on the quality of the novel: that it expends itself in banalities and stupidities; that the characterization is poor; that the jumping chain of events is poorly motivated and the narrative style is tasteless and simple. [28] Everything points to haste: the events are told like a news dispatch with zero-point focalization from the outside in the third person. The variation is always of the same theme in stereotyped repetition—namely, the endangerment of the chastity of the separated pair through a third person, described in varying places. [29] (See appendix 4.)

⁂

2§3. The confusing plot is quickly reported: [30] the extraordinarily beautiful Habrokomes is narcissistic and shuns the god Eros, who takes revenge upon Habrokomes. The young man falls madly in love with the beautiful Anthia during a procession for Artemis in Ephesos. Love at first sight leads to infinite sorrows and emotional turmoil. The concerned fathers seek advice from an oracle. The oracle prophesies misadventures and more trouble. In spite of this the parents consent to the marriage and send the pair on a harmless sea voyage for their honeymoon in their effort to appease the gods. After the pledge of eternal fidelity in Samos and a stop in Rhodes the ship is attacked by pirates. From now on, whoever—man or woman—meets the boy or the girl, falls instantly in love with them. And this fact obviously means that their oath of chastity is in jeopardy. Due to Habrokomes’ and Anthia’s sexual attractiveness the couple is quickly separated. In his search for the girl Habrokomes follows her trail through Phoenicia, Kilikia, and Kappodokia to Egypt. He goes eventually to Sicily, where Anthia is believed to be dead. Meanwhile Anthia, faced with the usual male attacks, follows a route through the Nile delta to the Ethiopian border and then back to Alexandria in order to come to Southern Italy. The plot gets complicated through a third agent, the good robber Hippothoos, who functions as an alter ego of the hero. He wanders through the world, too, and always comes in a more or less greater distance to Anthia. After Kilikia he manages to reach her in Upper Egypt; then, he buys her in Tarentum as a love slave. Finally, after a vortex of events, things come to a long delayed recognition scene and reunion in Rhodes, after Habrokomes takes a trip there via Crete and Cyprus from Noukerion, where he was working in a quarry. In Rhodes he comes across Hippothoos and Anthia, who in the meanwhile have left Tarentum. In this happy ending they all move back to Ephesos, where they live happily ever after. (See appendices 1 and 4.)

⁂

2§4. Relying on the attestation of Suda that the work comprised ten books (s. v. Ξενοφῶν [Adler III 495]), Erwin Rohde suspected that our edition is an epitome. [31] K. Bürger made then a dogmatic fact out of this theory. [32] Even today this thesis holds nearly as communis opinio. [33] The conjecture that the novel transmitted in only five books could have been merely a blueprint or an extract serves as a bridge to explain somehow the narrative’s shortcomings: the especially rushed staccato style, the often hardly recognizable motivations, the alleged lack of artistry, the abrupt transitions as well as the sudden appearances of previously unestablished characters. A specific novel type set as implicit norm stands behind this negative judgment—namely Chariton. Everything should go according to the laws of probability. Thus naturalistic storytelling is subconsciously laid out as the unmarked standard.

2§5. The anchoring of Xenophon in folk traditions has recently served as another possible explanation of the alleged faults. In this branch of research there are basically two directions: (1) The work is considered to be a sort of folk-book, which treats the plot as a type of fairytale. [34] (2) Others resort to the concept of oral poetry in the Homeric epics. Xenophon’s stylistic and narratological quirks would thereby result from a still considerable orality. [35] However, one cannot help but address the issue, whether Xenophon’s novel reflects actual orality in its composition, according to the theory of Milman Parry and Albert Lord.

2§6. Is it possible that Xenophon writes on the foundation of the artistic movement of the second Sophistic? Behind the simple and linear story line hides a complex structure. According to Scarcella the “climactic trajectory” of the course of development, which culminates in the recognition, is split into uncountable moments of individual adventures. Framed by two dreams (1.12.4; 5.8.5), these in turn imitate, in a certain degree, a “monadic spherical dimension.” The analogies drawn between the intermediate figures like Hippothoos as well as Leukon and Rhode increase the sense of unity in the whole segmentation. The novel creates the impression of a vertiginous development. The “slowed acceleration,” the massing of experiences as a chain of mechanical repetitions and variations as well as the “primultimity of the first time,” in the sense of Vladimir Jankélévitch, should be noted. Here narration is built less on showing, but rather on telling—that is on summarizing, where the author does not insert himself into the story. The extradiegetic and heterodiegetic zero-point focalization of an omniscient narrator with a slight internal focalization becomes an intentional device of style. [36]

III. Autobiographical Inscription and Religion

3§1. The relief-like representation copies the traumatic effect of a tableau, of a picture series of countless horrible snapshots. As is well known, the Greek novel converts other levels of artistic expression into its so-called Schriftkunst. The structure of Xenophon is overall due to a mimesis of an ‘autobiographical’ inscription. [37] At the very end the two heroes consecrate their tale of woe as a votive autobiography to the goddess Artemis in the temple at Ephesos (θύσαντες ἄλλα ἀνέθεσαν ἀναθήματα καὶ δὴ καὶ τὴν γραφὴν τῇ θεῷ ἀνέθεσαν πάντων ὅσα τε ἔπαθον καὶ ὅσα ἔδρασαν, 5.15.2). [38] There are quite a few hints that the story presents a long oversized epigram for the gods’ veneration. γραφή can, of course, also mean a book that is left in the sanctuary. [39] Then it would be identical with the existing script. Framing the story in such an attesting device is, as is well known, a feature of the novel. [40] The sequential style of Xenophon, thus, corresponds here to summary monumentalisation of the couple on a stone or in a sacred book.

3§2. The motive of the votive inscription is, to a certain degree, the late pragmatic and historical anchoring. The fiction gravitates to the form of an autobiography, at least of a certain phase in the life of two lovers. Xenophon copies this form of γραφή when possible and composes his story by imitating another genre which is based on the aretalogical list of facts and wonders. [41]

3§3. The gap, the yearning for the absent person, is thus externalized and unfolds in space. [42] At the same time, Xenophon points towards a religious dimension with Helios and Isis. Isis as the savior (σώτειρα) from emergencies becomes the deity who protects the lovers. The death experiences of the hero on the bank of the Nile are associated with the mystery experience of death and rebirth. Before all else, the trip through Egypt becomes closely linked with Isis. The fictive consecration as an excuse before Psammis (3.11.4–5), the identification as Memphitis before Hippothoos (4.3.6), the fatal confrontation with the Egyptian dogs in the pit (4.6.3–7), the flight into the sanctuary of Isis in Memphis (5.4.6–7) and the oracle at the shrine of Apis (5.4.8–11) endow the story with a religious sense, which Egypt as a holy landscape is able to transmit. [43] Further, Magna Graecia is also a place of mysterious experiences, even if the choice of scene here is in part due to the associations with wealth and erotic purchases. [44] Moreover, the story is connected with Helios, the Sun god, as, for example, in the framing in Rhodes, Egypt, and Ethiopia, whose inhabitants “are divided in two, the remotest of men, at the setting and the rising of the sun” (Odyssey 1.23–24). [45] In this borderland, where the sun both sets and rises again, begins the peripeteia that leads to salvation. Here, too, the heroine almost perishes and is revived (4.6.4–7). All in all, the plot can be combined with the cosmic journey of the sun from east to west, from Phoenicia via the axis of Egypt and Ethiopia to Southern Italy. Here the fast sea journey from there to the central island of Helios, Rhodes, eventually hints at the subterranean journey of the sun in the bark from Occident to Orient. [46]

3§4. On the other hand, it is very questionable whether we really should read the novel with Reinhold Merkelbach as a mystery novel. Under Karl Kerényi’s influence he sees the plot in every detail as a novel-like aretalogy for Isis. [47] Merkelbach attempts to find many ritual relationships with astonishing acumen. Instead, I maintain that the author used religion, myth, and ritual like other reference texts of the contemporary world as intertextual discourses, upon which he constructs his plot sequences. Mystery cults are present everywhere and reflect the identity crisis of the individual as well as the hope of salvation. Xenophon apparently attempts to enrich his elaborate story with religious meaning that cannot actually be found. [48]

IV. Space—Dream

4§1. We have described the concept of space in the novel as a tropological manifestation of love, which is constituted by a typical experience of lack. This is projected onto a spatial axis as a series of terrible threats and syntagmatically transferred on the episodes of robbery, victimization, violence, death, shipwreck and fire. I suggest that Xenophon’s fictional story bears a resemblance to a dream sequence because of its imaginary and oneiric quality. [49] The considerably unspecified encounter with the other becomes in its abominable and horrible nature an inner journey in timelessness. Like in a dream, happenstance piles on happenstance in an associative way. Without plan and guide the heroes rush through the world of the Mediterranean just as if they were blind, until they reappear at the end in Rhodes from the whirlpool of the accelerated adventures. The clever ring composition and the detailed recognition of the separated lovers extended over many steps parallel this process on the narrative level. Namely, the actual wanderings are framed by a stop on Rhodes and a reference to the panoply consecrated there, while between 1.12.2 and 5.10.6–10 the events automatically spin as though they are stuck in a spherical dimension. [50] In this respect, Bernhard Kytzler rightly calls the world of Xenophon “Kafkaesque”. [51] The heroes move aimlessly, like hamsters in a wheel. (See appendices 2 and 3.)

4§2. In addition, the numerous adventures are bordered by two dreams. After intermediate stops in Samos and Rhodes the trip proceeds well toward Egypt, until the wind drops and there is a calm. The sailors drink and become reckless. [52] Suddenly a superhuman frightful woman in red clothes (ἐσθῆτα ἔχουσα φοινικῆν 1.12.4) appears to the bridegroom Habrokomes in a dream. Then the waves of terror set in. Red, the color of fire and blood, is transferred to the Φοίνικες, the Phoenician pirates who attack the ship (1.13.1). Here the narration unmistakably falls into the pattern of a nightmare. Seemingly without orientation the characters drift like marionettes through space, until they finally break out of the chaotic cycle of events and find themselves back in the normal world. A second dream (5.8.5–6) is decisive for this transition. In Tarentum an image of her lover in his full beauty appears to Anthia. Then another beautiful woman comes forward and snatches Habrokomes away from Anthia. Afterwards she will set out on a journey homeward bound. What is in between is not actually explicit or marked as a dream, but indeed gives such an impression.

4§3. In this respect, Hippothoos, the good robber, is especially interesting. [53] He bounces here and there as mediator between the two characters. In 2.8.2, right after the final separation from his beloved in the Manto-episode, Habrokomes dreams in prison that his father wanders in a black robe over land and sea but finally comes into the dungeon and frees him from his chains. Afterwards he sees himself as a horse (ἵππον γενόμενον) pursuing another feminine horse over the whole globe, only to find her at last and again become human. The dream as well as the oracle function as prolepsis and at the same time as symbolic and associative dissemination. [54] Here, as far as motifs are concerned, the different symbolic fields of meaning are interwoven. The protagonist changes at times into a horse or an ass in traditional stories and roams the world as a curious initiate in order to find out (εὑρεῖν) the point of the wish, the mystery, or in this case, the partner. [55] The horse primarily functions as a symbol of young man’s initiation into the realm of maturity. [56] Finally, the horse signifies that which is instinctively driven in the famous metaphorical vehicle of souls in Plato’s Phaedrus. The bandit is named Hippo-thoos ‘fast stallion’. He is, so to speak, the alter ego governed by his instincts, [57] who embodies homosexuality and aggressive erotic inclinations against the heroine. Hippothoos is several times involved in the near death of the heroine. He is not able to recognize her in Egypt, because she assumes a new identity as Memphitis for the purpose of the escape from the proposals of Psammis (4.3.6). And also later in Tarentum he sees in her only the alleged Egyptian girl (5.9.5–7). The many levels of the process of anagnorisis with Hippothoos are already part of the endlessly retarded recognition. The female protagonist develops, in a sense, into a pure initiate of Isis. Yet Hippothoos, the homosexual robber, also falls in love with her at last and wishes to possess her sexually (5.9.11). Only at this critical moment she lets herself be recognized as the wife of Habrokomes. Then they go looking for the hero together and eventually find him again in Rhodes. (See appendices 2 and 3.)

4§4. The metadiegetic narrations intensify the confusion of the symbolic and oneiric dimension. At the end of book 2 Habrokomes and Hippothoos meet. Although he had just almost sacrificed Anthia, Habrokomes immediately begins a friendship with him (2.14). Together they go to Mazakon, where Hippothoos tells his story about his unhappy love to Hyperanthes—a sort of autobiography in the autobiography (3.2). The embedded account serves as a kind of false mirror to the history of our couple. Hyperanthes is the excess of Anthia, the beloved in full bloom. But Aristomachos, the “best fighter,” buys the boy. Hippothoos follows them to Byzantium, kills the rival, and flees across the sea. A shipwreck befalls them, and the boy drowns. [58] The second metadiegesis uttered by the fisherman Aigialeus in Syracuse once again thematizes Eros, the robbery of the lovers, as well as purity and loyalty even beyond death. All versions can be seen as variations on one theme, namely that of a love that is not safe and one sought with too much passion. Like in a dream, Xenophon reflects the excessive passion and threatening loss of chastity and gives them the shape of a novel according to the criteria of combination and selection. [59]

4§5. The author, like all writers of novels, deals with the important biographical threshold of marriage, which was ritually acted out in ancient Greece as a special turning point in life. [60] The fictional text mirrors exactly this liminal experience and the love situation before the reunion. Afterward, in a kind of dream sequence on the level of a fairytale folk structure, the suppressed fears and πάθη are acted out. In the expression of these fears we are freed from them by a kind of catharsis. From a simple novel of love and adventure a step is taken toward internalization.

V. Decentration of the Self, Dissemination, and the Chain of Signifiers

5§1. While the dream in ancient Greek literature deals primarily with foreshadowing and guiding the reader, [61] the oneiric in the center of Xenophon’s narration turns into material of artistic style. In the following, I will not concern myself with an analysis in the sense of Sigmund Freud, who wanted to discover the latent meaning in the contents of a dream and thereby bring it to consciousness. His psychoanalytical goal consisted of finding out the deeper meaning hidden behind the superficial. The sentence in the thirty-first of his “Neue Vorlesungen” is famous: “where Id was should become Ego.” Rather, I defer to Jacques Lacan, who sees the existence of the subject in the “Id.” He starts from a split and the fundamentally deficient structure and combines the ex-centric state of the subject in the sense of the linguistic turn with Ferdinand de Saussure and Roman Jakobson. Thus, Lacan’s central thesis reads: the “Ego” constitutes itself on the basis of chains of signifiers via the supplementarity of symbols in the tropological game of metaphor and metonymy—or in his own words, the subject is nothing different than a “glissement incessant du signifié sous le signifiant.” [62] The subject thus succumbs to the structure of language, and meaning emerges only in the referential game of signs. And already Roman Jakobson has associated the characteristic work of dream with the two axes of language, the paradigmatic and syntagmatic, which correspond to metaphor and metonymy in Lacan’s linguistic fiction. [63]

5§2. I thus assume that composing his work according to similar criteria is a part of Xenophon’s intention as an artist. From this perspective all the so-called faults are explained as a conscious stylistic choice. Against the background of such a decentralized understanding of the self it also becomes clear why I have emphasized the epigraphical character of an “autobiography” of the two lovers. Like the Nouveau Roman and the postmodern new autobiography—take one of Serge Doubrovsky’s, for instance—which proves to be an “Autofiktion,” [64] the inscription loses its control over real incidents, since the love novel is ultimately based on fiction that it is anchored in actuality by strategies of assertion and believability. The fictional text as an autobiographical epigram constructs the events post festum and, so to speak, monumentalizes the “I” of both protagonists with it. [65]

5§3. But I want to draw on Lacan merely as a starting point and actually make the discourse of love responsible for the dissolution of the “I” and the pluralization of meaning. For Xenophon is certainly not concerned with philosophical or psychoanalytical reflections on the subject, but only with the task of writing a love novel according to specific generic conventions. But, in the same way as according to Lacan the subject extracts itself because of its constitutive lack and gives space to semiosis, so we have seen that a lover loses control of himself because of excessive emotion. Love is also felt in our novel to be a disease (1.4–5). The protagonists wither away, then the fathers send out people in order to consult the oracle of Apollon in Kolophon (1.5.5–9). The often-criticized reply of the gods is typically ambiguous from the point of view of plot motivation. [66] On the level of plot, an oracle serves, in the same way as a dream, as prolepsis, i.e. a preview to the continuing chain of events. [67] But here it is an additional part of “dissemination,” the pluralization of meaning that Eros tends to cause. Part of the nature of oracles is that they are not clear, because there are many ways to interpret them. Earlier research did not recognize that nearly all contents of the oracle were simply confined to the sickness of love in a metaphorical way. [68]

5§4. Marriage is truly the desired goal. In the reunion of the marriage night the pathos they release in an intensive emotion, the full decentralizing of the “I” of both, comes to light in an especially impressive manner (1.9). [69] After the erga of love, the agonizing fight in bed, an end seems to be reached to the pains. The day after they are doing splendidly; all of life seems to be a party and full of celebration (ἑορτὴ δὲ ἦν ἅπας ὁ βίος αὐτοῖς καὶ μεστὰ εὐωχίας πάντα, 1.10.2). They forget the oracle, since it is fulfilled in a simple way. Now comes a little intervention of the narrator: “but destiny had not forgotten it” (1.10.2). Those who misunderstood the oracle trigger the events. They do precisely what they really want to avoid. For παραμυθία (παραμυθήσαθαι τὸν χρησμόν, 1.7.2 and 1.10.3), for reassurance and abatement, the pair go on a trip, so to speak a honeymoon, to Egypt. But this is exactly the place they should avoid because of the predicted disaster. From the perspective of irony, the unnecessary and wrong interpretation of the symbols make this oracle so important. It represents the lack of reference on the side of the “autobiographers” narrating the story. From the point of view of the psyche, the reunion runs astray too abruptly. The desire cannot be relieved completely in the first sexual encounter. In addition, the primae noctis experience is of such intensity that the ex-centric structure of the self of both of them who are in the process of dissolution cannot be simply inverted all of a sudden. Infinite desire expands and unfolds in space.

5§5. The discourse of absence that characterizes love finds expression in the spaciousness of the Mediterranean world, which in turn represents the spatial precondition of the extensive fictional prose. Longing and lack become traceable in the auto-annulment of meaning. Subjects and clear referentialities of signifiers upon a signified extract themselves in order to give space to the free floating of signifiers. The splitting of the male hero into two figures, the missed and partial anagnorisis, and the extremely slow pace over many levels until the final re-finding of the lovers elucidate the gap between signifier and signified. The search for a sign and the supplement for the lost other turn into the key theme. As is well known, traditional symbols belong to the original structure of recognition in fairytales. [70] The consecrated panoply, the tablet to their memory, and the sacrifice of hair by Anthia serve as such σήματα for the anagnorisis. [71] The epigrams embedded into the text function as a construction and a replacement of an absent voice. Other voices come to life only in reading; the signs of the language thus make possible the rebirth of the sought love. [72] The connection between signifier and signified is, however, only arbitrary. Through it the supplementary structure becomes clear. The difference turns to différance, to the deferral of meaning and happy end.

5§6. The sign should represent, i.e. at least replace the absent partner. Habrokomes becomes certain of the death of his beloved in Egypt and goes to Sicily and Southern Italy on a search for a sign of her. The seeker of the real form, who at the time limps a stop behind, is reduced to a seeker of a representation of the desired person. The hero goes off on the trip relatively unmotivated and is suddenly a step in front. The concrete pursuit turns from this point into a chase in the wrong direction. The figures come near each other merely through happenstance in Southern Italy, barely miss each other, but in Tarentum they finally come to the first re-recognition. The total route in space turns into trace of the other which has withdrawn itself. [73] The theme of the supplementarity of signs is intensively highlighted in the metadiegesis of the fisherman Aigialeus (5.1.4–11). His wife Thelxinoe, acquired in an adventure, has just recently died. In the form of a mummy he preserves a specific sign of her identity. This is not only arbitrary, but even presents the mummified body covering of the represented person who indeed lacks both life and soul, that is, the kernel of identity. In his loss the decentralized man makes do with a paradoxical replacement with which he eats and sleeps. Habrokomes has also set out to find a compensation for his lack and searches for the body of his supposedly dead beloved. [74]

5§7. Finally, I want to bring to attention how the author carries these gaps inscribed in love over to his fictional story as the floating chain of signifiers in the tropological game of metaphor and metonymy. After the abrupt and intensive fusion of souls (1.9), the fear of separation returns. Possible assaults through a third person that thematize the loss of sworn fidelity and chastity are projected onto the space. We fall into the yawning chasm of a nightmare. This is expressed in the oneiric association of episodes, where, just like in a textile fabric, one sign is interwoven with another. In the Greek imagination weaving and sewing are closely associated with the process of textualization. [75] The traditional ‘speaking names’ are important catalysts for movement. Habrokomes, he “of the luxurious hair”, and Anthia, she “who is blooming”, embody the beauty of youth. [76]

5§8. Let us begin with the sudden calm on their journey from Rhodes to Egypt (1.12.3), the dream of Habrokomes (1.12.4) and the following assault on their vessel (1.13). The transition of signifiers from φοινικῆν to Φοίνικες, i.e. from blood-red clothing to the Phoenician pirates, we have already discussed above. Korymbos, “the ship’s figurehead” or the “braided hair tuft,” [77] and Euxeinos, the “well-meaning guest-friend,” attack the couple. Their chief Apsyrtos, who possesses the same name as the brother Medea dismembered and thrown into the sea, is connected with the teacher of Habrokomes who remains behind with the other corpses in the water (1.14.4–6)—Apsyrtos’ daughter Manto with the disseminating oracle. Moiris alludes to moira, the fate; the name of the goatherd Lampon refers to the brilliance of marriage and to some hidden illumination or enlightenment in the context of mysteries. We have already touched on Hippothoos, “fast stallion”, and his role as alter ego of the hero. [78] No wonder that he is connected with the practice of human sacrifices for Ares. This in turn refers to Ares’ presentation on the wedding canopy (1.8.3) and to Areia, an Egyptian village Hippothoos plundered (5.2.4; 5.2.7). The eirenarch Perilaos, who “stands above the people” or “cares about the people,” has liberated the heroine and also lies in wait for her (2.13.3–8). In Hippothoos’ metadiegesis Hyperanthes is the parallel to Anthia (3.2). The story refers to the practice of pederasty before marriage and complements the picture of Eros with homosexual love. The poison of the doctor Eudoxos, he “of a good reputation”, who comes from Ephesos like the author and the heroes, turns into a remedy against Perilaos’ propositions. The apparent death mirrors the death experience of the bride (3.4–6). Robbers break the grave open and she is sold to the “desert sandman” Psammis (3.8.3–3.9.1; 3.11), whose name refers to pharaoh Psammetich and anticipates the Egyptian trip (4.3.1–4). Meanwhile, the horny bitch Kyno lusts after Habrokomes (3.12.3). Dogs then play a role in the death pit of Anthia. For self-defense against Anchialos, who wanted to rape her, she is condemned to be buried in a pit with two Egyptian dogs watching her. They ought to rip her to shreds while living and then consume her (4.5.1–4.6.4). Amphinomos, who alludes to the just and noble suitor in the Odyssey (esp. 16.394–398), rescues her from the male robbers threatening her chastity. He feeds the hungry dogs with meat and only later becomes hungry for her. [79] The wild animals are simultaneously connected with Kerberos, the dog of the underworld, which can be associated with Anthia’s pit, and here in Egypt with Anubis, the jackal-like god of mummification, which in turn prefigures Thelxinoes’ condition in Sicily (5.1.9–11). In Koptos (5.2.6), which is punningly associated with κώπτω, “to strike,” Amphinomos is struck down and caught by Polyidos (5.4.3). As “a frequent onlooker,” he puts the safety of the heroine once more in question (5.4.5). His gaze of desire anticipates the prostitution scene in Tarentum (5.5.4–8; 5.7.1–2). There, Anthia’s simulated epilepsy (5.7.3–4) expresses the opposite of an orgasm and the total decentralizing of the self. She claims that a ghost put a hand on her and this explanation of the sacred disease includes again the theme of a sexual threat (5.7.6–9). [80] Hippothoos then acquires Anthia who is up for sale (5.9.4–9). Meanwhile Habrokomes is working in a quarry (5.8.1–4). The hard work of breaking the earth and splitting the rocks again symbolizes love and the vain search for the lost object. After the recognition which is delayed and postponed over many phases, we break out of the chain of signifiers constituing the kernel of the plot.

VI. Results

6§1. The detailed analysis of the spatio-temporal relationship in the novel of Xenophon of Ephesos has shown that space is necessary as a projection area for longing. Love as the discourse of absence is externalized in its constitutive lack and unfolds as space, which in turn releases more space for fiction. The associative floating between language and space makes the novel a journey. However, this is no trip to learn about oneself in encounters with the foreign, but rather an inner metaphorical wandering that thematizes the liminal crisis of marriage as a rite of passage for young men on the threshold of adulthood. [81] The spatial and temporal dimension is no longer, as with Bakhtin, disparaged in a negative sense, but rather we have determined the chronotope and the adventure in relation to love which is constitutive for the genre. Space is not only abstract, but also specific places enrich the story with meaning. Xenophon’s alleged shortcomings of composition and style have proved to be a conscious form of the adequate transposition of erotic discourse. The search for signs and the signified hidden behind them is less an expression of a meaningless world than the expression of Eros as a disease that decentralizes the self. Space proves to be dream, and both determine the extension and the form of (auto)fiction in their interdependence with time.

Appendix I. Plot Structure

Appendix II. Map and Legend

Appendix III. Routes

Appendix IV. Actions Step by Step

Bibliography

Algra, G. A. 2001. Der Neue Pauly 10:788–791, s.v. “Raum.”

Bakhtin, M. M. 1981. The Dialogic Imagination. Trans. C. Emerson and M. Holquist. Austin.

Ballengee, J. R. 2005. “Below the Belt: Looking into the Matter of Adventure-Time.” In Branham 2005:130–163.

Barthes, R. 1979. A Lover’s Discourse. Fragments. Trans. R. Howard. London.

Bierl, A. 1994. “Apollo in Greek Tragedy: Orestes and the God of Initiation.” Apollo: Origins and Influences (ed. J. Solomon) 81–96 and 149–159. Tucson and London.

———. 2001. Der Chor in der Alten Komödie: Ritual und Performativität (unter besonderer Berücksichtigung von Aristophanes’ Thesmophoriazusen und der Phalloslieder fr. 851 PMG). Munich and Leipzig. Translated in English by A. Hollmann as Ritual and Performativity: The Chorus in Old Comedy, Cambridge, MA, 2008.

———. 2002. “Charitons Kallirhoe im Lichte von Sapphos Priamelgedicht (Fr. 16 Voigt). Liebe und Intertextualität im griechischen Roman.” Poetica 34:1–27.

———. 2007. “Mysterien der Liebe und die Initiation Jugendlicher. Literatur und Religion im griechischen Roman.” Literatur und Religion II. Wege zu einer mythisch–rituellen Poetik bei den Griechen (eds. A. Bierl, R. Lämmle, and K. Wesselmann) 239–334. MythosEikonPoiesis 1.2. Berlin and New York.

Bowersock, G. W. 1994. Fiction as History. Nero to Julian. Berkeley.

Branham, R. B. 1995. “Inventing the Novel.” Bakhtin in Contexts: Across the Disciplines (ed. A. Mandelker) 79–87 and 200. Evanston.

Branham, R. B. 2002. “A Truer Story of the Novel?” Bakhtin and the Classics (ed. R. B. Branham) 161–186. Evanston.

———, ed. 2005. The Bakhtin Circle and Ancient Narrative. Ancient Narrative, Suppl. 3. Groningen.

Brooks, P. 1984. Reading for the Plot: Design and Intention in Narrative. Oxford.

Bürger, K. 1892. “Zu Xenophon von Ephesus.” Hermes 27:36–67.

Carson, A. 1986. Eros: The Bittersweet. An Essay. Princeton.

Casey, E. S. 1997. The Fate of Place: A Philosophical History. Berkeley.

Chew, K. 1998. “Inconsistency and Creativity in Xenophon’s Ephesiaka.” Classical World 91:203–213.

Clarke, K. 1999. Between Geography and History: Hellenistic Constructions of the Roman World. Oxford.

Connors, C. 2002. “Chariton’s Syracuse and Its Histories of Empire.” In Paschalis and Frangoulidis 2002:12–26.

de Man, P. 1979. “Autobiography as De-Facement.” Modern Language Notes 94:919–930.

Doody, M. A. 1996. The True Story of the Novel. New Brunswick.

Dougherty, C. 2001. The Raft of Odysseus: The Ethnographic Imagination of Homer’s Odyssey. Oxford.

Dougherty, C., and L. Kurke, eds. 1993. Cultural Poetics in Archaic Greece: Cult, Performance, Politics. Cambridge.

Dowden, K. 1999. “Fluctuating Meanings: ‘Passage Rites’ in Ritual, Myth, Odyssey, and the Greek Romance.” Rites of Passage in Ancient Greece: Literature, Religion, Society (ed. A. Padilla) 221–243. Bucknell Review 43.1. Lewisburg.

Foley, J. M. 1997. “Traditional Signs and Homeric Art.” Written Voices, Spoken Signs: Tradition, Performance, and the Epic Text (eds. E. Bakker and A. Kahane) 56–82. Cambridge, MA and London.

Foust, R. 1981. “The Aporia of Recent Criticism and the Contemporary Significance of Spatial Form.” In Smitten and Daghistany 1981:179–201.

Frank, J. 1945. “Spatial Form in Modern Literature.” Sewanee Review 53:221–240, 433–456, 643–653. Reprinted 1963 in The Widening Gyre: Crisis and Mastery in Modern Literature, 3–62, New Brunswick.

Frank, M. 1983. Was ist Neostrukturalismus? Frankfurt am Main.

Frye, N. 1976. The Secular Scripture: A Study of the Structure of Romance. Cambridge, MA.

Fusillo, M. 1989. Il romanzo greco. Polifonia ed eros. Venice.

Gärtner, H. 1967. Paulys Realencyclopädie der classischen Altertumswissenschaft IX-A-2, 2055–2089, s.v. “Xenophon von Ephesos.”

Genette, G. 1994. Die Erzählung. Munich.

Girard, R. 1961. Mensonge romantique et vérité romanesque. Paris.

Görling, R. 1997. Heterotopia: Lektüren einer interkulturellen Literaturwissenschaft. Munich.

Griffiths, J. G. 1978. “Xenophon of Ephesus on Isis and Alexandria.” Hommages à M. J. Vermaseren I (eds. M. B. de Boer and T. A. Edridge) 409–437. Leiden.

Gronemann, C. 1999. “‘Autofiction’ und das Ich in der Signifikantenkette. Zur literarischen Konstitution des autobiographischen Subjekts bei Serge Doubrovsky.” Poetica 31:237–262.

Hägg, T. 1966. “Die Ephesiaka des Xenophon Ephesios—Original oder Epitome?” Classica et Mediaevalia 27:118–161.

Hägg, T. 1971a. Narrative Technique in Ancient Greek Romances: Studies of Chariton, Xenophon Ephesius and Achilles Tatius. Stockholm.

———. 1971b. “The Naming of the Characters in the Romance of Xenophon Ephesius.” Eranos 69:25–59.

Hansen, W. 2003. “Strategies of Authentication in Ancient Popular Literature.” In Panayotakis, Zimmerman, and Keulen 2003:301–314.

Hartog, F. 1988. The Mirror of Herodotus. Trans. J. Lloyd. Berkeley.

———. 1996. Mémoire d’Ulysse: récits sur la frontière en Grèce ancienne. Paris.

Helm, R. 1956. Der antike Roman. 2nd ed. Göttingen.

Henne, H. 1936. “La géographie de l’Égypte dans Xénophon d’Éphese.” Revue d’Histoire de la Philosophie et d’Histoire générale de la Civilisation 4:97–106.

Hölscher, U. 1988. Die Odyssee: Epos zwischen Märchen und Roman. 2nd ed. 1989. Munich.

Holzberg, N. 1996. “The Genre: Novels Proper and the Fringe.” In Schmeling 1996:11–28.

Hübner, K. 1985. Die Wahrheit des Mythos. Munich.

Hunter, R., ed. 1998. Studies in Heliodorus. Cambridge.

Iser, W. 1979. “Die Wirklichkeit der Fiktion—Elemente eines funktionsgeschichtlichen Textmodells.” Rezeptionsästhetik (ed. R. Warning) 277–324. 2nd ed. Munich.

———. 1983. “Akte des Fingierens oder: Was ist das Fiktive im fiktionalen Text?” Funktionen des Fiktiven (eds. W. Iser and D. Henrich) 121–151. Munich.

Jakobson, R. 1971. “Two Aspects of Language and Two Types of Aphasic Disturbances.” Roman Jakobson. Selected Writings. Vol. 2, Word and Language, 239–259. The Hague and Paris.

Kerényi, K. 1927. Die griechisch–orientalische Romanliteratur in religionsgeschichtlicher Beleuchtung. 3rd ed. 1973. Darmstadt.

König, J. 2007. “Orality and Authority in Xenophon of Ephesus.” Seeing Tongues, Hearing Scripts: Orality and Representation in the Ancient Novel (ed. V. Rimell) 1–22. Ancient Narrative, Suppl. 7. Groningen.

Konstan, D. 1994a. Sexual Symmetry: Love in the Ancient Novel and Related Genres. Princeton.

———. 1994b. “Xenophon of Ephesus: Eros and Narrative in the Novel.” Greek Fiction: The Greek Novel in Context (eds. J. R. Morgan and R. Stoneman) 49–63. London and New York.

———. 2002. “Narrative Spaces.” In Paschalis and Frangoulidis 2002:1–11.

Kytzler, B. 1996. “Xenophon of Ephesus.” In Schmeling 1996:336–360.

Lacan, J. 1966. Ecrits I. Paris.

Lalanne, S. 2006. Une éducation grecque. Rites de passage et construction des genres dans le roman grec ancient. Paris.

Laplace, M. 1983. “Légende et fiction chez Achille Tatius: les personnages de Leucippé et de Iô.” Bulletin de l’Association Guillaume Budé 1983:311–318.

———. 1994. “Récit d’une éducation amoureuse et discours panégyrique dans les Éphésiaques de Xénophon d’Éphèse: le romanesque antitragique et l’art de l’amour.” Revue des Études Grecques 107:440–479.

Liatsi, M. 2004. “Die Träume des Habrokomes bei Xenophon von Ephesos.” Rheinisches Museum 147:151–171.

Lowe, N. J. 2000. The Classical Plot and the Invention of Western Narrative. Cambridge.

Marinatos, N. 2001. “The Cosmic Journey of Odysseus.” Numen 48:381–416.

Martin, R. P. 2002. “A Good Place to Talk: Discourse and Topos in Achilles Tatius and Philostratus.” In Paschalis and Frangoulidis 2002:143–160.

Menke, B. 1993. “De Mans ‘Prosopopöie’ der Lektüre: Die Entleerung des Monuments.” Ästhetik und Rhetorik: Lektüren zu Paul de Man (ed. K. H. Bohrer) 34–78. Frankfurt am Main.

Merkelbach, R. 1962. Roman und Mysterium in der Antike. Munich and Berlin.

———. 1995. Isis regina—Zeus Sarapis: Die griechisch–ägyptische Religion nach den Quellen dargestellt. Stuttgart. 2nd ed. 2001. Munich and Leipzig.

Möllendorff, P. 1995. Grundlagen einer Ästhetik der Alten Komödie: Untersuchungen zu Aristophanes und Michail Bachtin. Tübingen.

Moretti, F. 1998. Atlas of the European Novel 1800–1900. London.

Muschg, A. 1996. “Der Raum als Spiegel.” In Reichert 1996a:47–55.

Nagy, G. 1990. Pindar’s Homer: The Lyric Possession of an Epic Past. Baltimore and London.

———. 1996. Poetry as Performance: Homer and Beyond. Cambridge.

Olsson, G. 1996. “Die Projektion des Begehrens/Das Begehren der Projektion.” In Reichert 1996a:225–249.

O’Sullivan, J. N. 1995. Xenophon of Ephesus: His Compositional Technique and the Birth of the Novel. Berlin and New York.

———, ed. 2005. Xenophon Ephesius: De Anthia et Habrocome Ephesiacorum libri V. Munich and Leipzig.

Panayotakis, S., M. Zimmerman, and W. Keulen, eds. 2003. The Ancient Novel and Beyond. Leiden and Boston.

Paschalis, M., and S. Frangoulidis, eds. 2002. Space in the Ancient Novel. Ancient Narrative, Suppl. 1. Groningen.

Perry, B. E. 1967. The Ancient Romances: A Literary-Historical Account of Their Origins. Berkeley and Los Angeles.

Puiggali, J. 1986. “Une histoire de fantôme (Xénophone d’Ephèse V 7).” Rheinisches Museum 129:321–328.

Reardon, B. P. 1991. The Form of Greek Romance. Princeton.

———. 2004. “Variation on a Theme: Reflections on Xenophon Ephesius.” ENKUKLION KHPION (Rundgärtchen): Zu Poesie, Historie und Fachliteratur der Antike. Festschrift für Hans Gärtner (ed. M. Janka) 183–193. Munich and Leipzig.

Reichert, D., ed. 1996a. Räumliches Denken. Zürich.

Reichert, D. 1996b. “Räumliches Denken als Ordnen der Dinge.” In Reichert 1996a:15–45.

Rohde, E. 1876. Der griechische Roman und seine Vorläufer. Leipzig. 5th ed. 1974. Darmstadt.

Ruiz-Montero, C. 1994. “Xenophon von Ephesos: Ein Überblick.” Aufstieg und Niedergang der römischen Welt II.34-2:1088–1138. Berlin and New York.

———. 2003. “Xenophon of Ephesus and Orality in the Roman Empire.” Ancient Narrative 3:43–62.

Sartori, F. 1985. “Italie et Sicilie dans le roman de Xénophon d’Éphèse.” Journal des Savants 1985:161–188.

Scarcella, A. M. 1979. “La struttura del romanzo di Senofonte Efesio.” La struttura della fabulazione antica, 89–113. Pubblicazioni dell’Istituto di Filologia Classica dell’Università di Genova 54. Genoa. Reprinted 1993 in Romanzo e romanzieri II, 165–184, Perugia.

Schmeling, G. L. 1980. Xenophon of Ephesus. Boston.

———, ed. 1996. The Novel in the Ancient World. Leiden.

Schmitz, T. A. 2002. Moderne Literaturtheorie und antike Texte: Eine Einführung. Darmstadt.

Seaford, R. 1987. “The Tragic Wedding.” Journal of Hellenic Studies 107:106–130.

Selden, D. L. 1998. “Aithiopika and Ethiopianism.” In Hunter 1998:182–217.

Sironen, E. 2003. “The Role of Inscriptions in Greco-Roman Novels.” In Panayotakis, Zimmerman, and Keulen 2003:289–300.

Slater, N. W. 2002. “Space and Displacement in Apuleius.” In Paschalis and Frangoulidis 2002:161–176.

Smitten, J. R., and A. Daghistany, eds. 1981. Spatial Form in Narrative. Ithaca and London.

Susanetti, D. 1999. “Amori tra fantasmi, mummie e lenoni: Sicilia e Magna Grecia nel romanzo di Senofonte Efesio.” Sicilia e Magna Grecia. Spazio reale e spazio immaginario nella letteratura greca e latina (eds. G. Avezzù and E. Pianezzola) 127–169. Padova.

Talbert, R., and K. Brodersen, eds. 2004. Space in the Roman World: Its Perception and Presentation. Münster.

Tepperberg, E. M. 1997. “Die pegasische Feuerwerksschrift des gespaltenen Kentauren in den Autofictions von (Julien) Serge Doubrovsky (*1928). Zur Aktualität des Bild- und Motivkomplexes um Reiter, Pferd und (Im)Potenz in der Gegenwartsliteratur: Ein Essay.” Literatur: Geschichte und Verstehen. Festschrift für Ulrich Mölk zum 60. Geburtstag (eds. H. Hudde and U. Schönung) 517–542. Heidelberg.

Tholen, G. C. 2002. Die Zäsur der Medien: Kulturphilosophische Konturen. Frankfurt am Main.

Vidal-Naquet, P. 1986. “Land and Sacrifice in the Odyssey: A Study of Religious and Mythical Meanings.” The Black Hunter: Forms of Thought and Forms of Society in the Greek World, 15–38. Trans. A. Szegedy-Maszak. Baltimore.

Walde, C. 2001. Die Traumdarstellungen in der griechisch-römischen Dichtung. Munich and Leipzig.

Watanabe, A. 2003. “The Masculinity of Hippothoos.” Ancient Narrative 3:1–42.

Welsch, W. 1996. Vernunft: Die zeitgenössische Vernunftkritik und das Konzept der transversalen Vernunft. Frankfurt am Main.

Whitmarsh, T. 1998. “The Birth of a Prodigy: Heliodorus and the Genealogy of Hellenism.” In Hunter 1998:93–124.

Whitmarsh, T. 2005. “Dialogues in Love: Bakhtin and His Critics on the Greek Novel.” In Branham 2005:107–129.

Winkler, M. M. 2002. “Chronotope as locus amoenus in Daphnis and Chloe and Pleasantville.” In Paschalis and Frangoulidis 2002:27–39.

Zeitlin, F. I. 1990. “Thebes: Theater of Self and Society.” Nothing to Do with Dionysos? (eds. J. J. Winkler and F. I. Zeitlin) 130–167. Princeton.

Zimmermann, F. 1949/50. “Die Ἐφεσιακά des sog. Xenophon von Ephesos. Untersuchungen zur Technik und Komposition.” Würzburger Jahrbücher f. d. Altertumswiss. 4:252–286. Reprinted 1984 in Beiträge zum griechischen Liebesroman (ed. H. Gärtner) 295–329, Hildesheim, Zürich, New York).

Footnotes

[ back ] 1. This is the slightly modified version of “Räume im Anderen und der griechische Liebesroman des Xenophon von Ephesos. Träume?,” in: A. Loprieno (ed.), Mensch und Raum von der Antike bis zur Gegenwart (Colloquium Rauricum 9), Munich/Leipzig 2006, 71–103. I thank my former exchange student Marquis Berrey (St. Olaf College) for the translation into English. For the technical preparation of the appendices 2, 3 and 4 I thank Pia and Doris Degen (Basel). I had the opportunity to present a first version at the Center for Hellenic Studies (2 Oct. 2003). I thank Greg Nagy for his rich comments and for accepting it for publication.

[ back ] 2. For actuality of space see Tholen 2002:112. In modern literary studies space has been prominent since Frank 1945. On the reception of Frank’s theory of spatial form see Smitten/Daghistany 1981. Furthermore see Görling 1997 and the references in Tholen 2002:112n2.

[ back ] 3. See Reichert 1996b:16–18. In general see Reichert 1996a.

[ back ] 4. Algra 2001:788–789. See also Casey 1997, esp. 75–78 and Clarke 1999:1–45.

[ back ] 5. See Muschg 1996.

[ back ] 6. On space in Greek literature in general see Doughtery/Kurke 1993; Hartog 1996; Lowe 2000, esp. 41–46. On Homer’s Iliad see Lowe 2000:111–114; on the Odyssey see Hölscher 1988:135–158; Hartog 1996:23–48; Vidal-Naquet 1986; Lowe 2000:132–137 and Doughtery 2001; on Herodotus see Hartog 1988; on tragedy see Zeitlin 1990 and Lowe 2000:164–165, 169–176; on Aristophanes see Möllendorff 1995:112–150 and Lowe 2000:87. On the concept of space in the Roman world see now Talbert/Brodersen 2004.

[ back ] 7. See among others Rohde 1876 and Helm 1956.

[ back ] 8. Bakhtin 1981:84–258.

[ back ] 9. Esp. Bakhtin 1981:86–110.

[ back ] 10. For a confirmation see Branham 1995 and 2002.

[ back ] 11. Konstan 1994a:46–47.

[ back ] 12. Konstan 2002 considers the different technique of the creation of an “action space.” He differs little from Bakhtin.

[ back ] 13. Paschalis/Frangoulidis 2002; see now the volume with the title “The Bakhtin Circle and Ancient Narrative” (Branham 2005) and my review (2006) in Museum Helveticum 63:227–228; in relation to our subject, the contributions of Ballengee 2005 and Whitmarsh 2005 are of particular interest.

[ back ] 14. See Connors 2002; besides Connors 2002 and Konstan 2002 in the volume on space (Paschalis/Frangoulidis 2002) esp. Martin 2002; Slater 2002 and Winkler 2002 are important for our question. See also Kerényi 1927:44–66; Bowersock 1994:29–53; Doody 1996:319–336; Lowe 2000:223–224, 226–228 (on Greek novel in general), 229 (on Chariton), 230 (on Xenophon of Ephesus), 234–235 (on Achilles Tatius), 235–236 (on Heliodorus). Lowe stresses also the relation to epic. For space and literary cartography in the modern European novel see Moretti 1998.

[ back ] 15. Bierl 2002:8–9.

[ back ] 16. Barthes 1979:13–17 (French original: Fragments d’un discours amoureux, Paris 1977, reprinted in: Roland Barthes. Oeuvres complètes. Tome III 1974–1980, ed. by E. Marty, Paris 1995, 471–474).

[ back ] 17. Carson 1986, esp. 10–76. Above all, she assumes that the primary reason for writing lies in this act of yearning. The lyric poet would understand the nature of love in writing (esp. 53–76). On a similar concept in figural art see Olsson 1996.

[ back ] 18. Carson 1986:77–95. The moment of the pathological schizophrenia in the monologue of the soul is extended and exploited. The reader finds himself in this triangle relationship and is swept along (83–85). On “triangulation” see also Fusillo 1989:219–228 with a reference to Girard 1961, esp. Chapter 1; on love and the space-time relationship in the novel see also Fusillo 1989:179–234, esp. 213–219.

[ back ] 19. For this insight I thank Horst Turk.

[ back ] 20. Compare the so-called fringe novels, the utopic report of the travel, the novel-like fictional biography and the early Christian novel-like literature; for this see Holzberg 1996.

[ back ] 22. See Sartori 1985 and Susanetti 1998.

[ back ] 23. On Hellenistic constructions of the Roman world see Clarke 1999.

[ back ] 24. See Reardon 1991:169–180, esp. with the table 174. He shows that psychological (Frye 1976), social (Perry 1967, Reardon 1991) and religious approaches (Kerényi 1927; Merkelbach 1962 and 1995) have their origin in a similar pattern of alienation.

[ back ] 25. On Xenophon and Egypt see Henne 1936 and Griffiths 1978; he thinks (426) that the author had his “Sitz im Leben” in Lower Egypt, especially in Alexandria.

[ back ] 26. Gärtner 1967:2059.

[ back ] 27. On Xenophon see among others Zimmermann 1949/50; Hägg 1966; Gärtner 1967; Scarcella 1979; Schmeling 1980; Konstan 1994b; Laplace 1994; Ruiz-Montero 1994; O’Sullivan 1995; Kytzler 1996; Chew 1998; Reardon 2004; König 2007. The text follows O’Sullivan 2005.

[ back ] 28. Rohde 1876:421–435; Gärtner 1967:2060–2072.

[ back ] 29. Scarcella 1979.

[ back ] 31. Rohde 1876:429.

[ back ] 32. Bürger 1892.

[ back ] 33. Hägg 1966 first opposed Bürger’s theses. The epitome theory has been shaken up since then, but still finds numerous adherents: see Ruiz-Montero 1994:1094–1096. Merkelbach 1962:91–113, esp. 91 and Kerényi 1927:58–63, 232–235 believed they could explain a few inconsistencies by assuming a later redaction dedicated to Helios. The novel, in the opinion of the authors, originally represented a pure Isis novel for initiates, who would find their mystery cult encoded in the book. Further, the novel was drafted in the first century BC, then revised after Chariton and finally recast in the mode of the cult of Helios-Sol-Invictus in the third century. For a critical reception of this theory see Gärtner 1967:2072–2080. On the mystery theses see below n47.

[ back ] 34. See Ruiz-Montero 1994:1096–1105. Certainly the narrator can feed his story off fairytales and fall back upon them. But it is highly questionable whether Xenophon is on the level of a fairytale. This question is simultaneously connected with the dating. There have always been attempts to date Xenophon before Chariton. But it is more likely the case that Xenophon falls back upon this folk-tale elements in a conscious deliberate act. See Reardon 2004. We would have here a development towards a fairytale likeness, against the evolutionary thesis of Moretti 1998.

[ back ] 35. O’Sullivan 1995; see now König 2007. Ruiz-Montero 1994:1112–1119 is right to say that Xenophon adjusts his style to a popular theme. She shows that these elements belong to the rhetorical concept of the apheleia at the time of the appearance of the work. She also proves that his style overall represents a mix of Koine and Atticism. See also Ruiz-Montero 2003.

[ back ] 36. Scarcella 1979, esp. 96–101; for a narratological analysis see also Hägg 1971a:49–63, 97–101, 120–124, 154–178, 197–201, 227–233, 267–277, 296–300. On the “primultimity” of the first time Scarcella 1979:96, according to Genette 1994:49.

[ back ] 37. Schmeling 1980:81, 107 and Laplace 1994:441 with n3 and n4 already pointed this out incidentally. See also Hansen 2003:308–309 (“light pseudo-documentarism” [309]). On inscriptions in the novel see Sironen 2003, in Xenophon ibid. 290–292. Merkelbach 1995:347–348 considers the Ephesiaka as “noch fast eine Aretalogie.”

[ back ] 38. Frequently our text alludes to consecrations and inscriptions, whose wording is written into the text as an epigram. The pair consecrates a panoply together with an inscription in Rhodes for Helios (1.12.2) (with a later reference [5.10.6]); Hippothoos composed a grave epigram for his drowned beloved (3.2.13) and Anthia leaves a votive inscription behind in the context of the offering of the lock of hair (5.11.6). See Sironen 2003:290–292.

[ back ] 39. See Hansen 2003:308n15. Merkelbach 1962:113 points to the deposition of such books, which served as an aretology of the goddess. These could be recited; in such aretalogies Merkelbach pinpoints the origin of the novel.

[ back ] 40. See Hansen 2003, esp. 308–309. Daphnis and Chloe, too, consecrated a picture series with scenes after their marriage that Longus converted into writing. The “I” narrator in Achilleus Tatios’ novel is set to thinking by the votive picture in the temple of Astarte in Sidon that presents the robbery of Europe. Heliodorus’ story is based on the inscription that has been given on the headband as a symbolon for Charicleia (4.8). The Adventures beyond Thule of Antonios Diogenes reproduces the story of Deinias that he had written on tablets and were deposited next to his grave in Tyre, then were found by a comrade of Alexander’s after the capture of the city.

[ back ] 41. There the author as well considerably remains behind the curtains. Likewise, as with Chariton, a statement on the author in the style of a historian’s introduction or a sphragis is also missing here. Rather, it presents the mimesis of another genre, namely the imitation of the autobiographical report or the commentarius in the third person, as Caesar published. Therefore, an autobiography does not have to be written in the first person. Precisely the inscription frequently demands the speech of a third person: cf. the expression (5.15.2) … καὶ δὴ καὶ τὴν γραφὴν τῇ θεῷ ἀνέθεσαν πάντων ὅσα τε ἔπαθον καὶ ὅσα ἔδρασαν.

[ back ] 42. Plato (Cratylus 420a4–5) makes the following statement on the discourse of absence: καὶ μὴν πόθος αὖ καλεῖται σημαίνων οὐ τοῦ παρόντος εἶναι, ἀλλὰ τοῦ ἄλλοθί που ὄντος καὶ ἀπόντος (“And again it is called longing, because it describes not something that is present, but rather that which is somewhere else and is absent”).

[ back ] 43. Griffiths 1978.

[ back ] 44. Susanetti 1999:156–157.

[ back ] 45. For the role of Ethiopia in the novel of Heliodorus see Whitmarsh 1998 and Selden 1998.

[ back ] 46. See Marinatos 2001, esp. 382–387 (on Egyptian context) and Hölscher 1988:149–155.

[ back ] 47. See Kerényi 1927:58–63; Merkelbach 1962:91–113; Merkelbach 1995:347–363. According to them both heroes reenact the story of Isis and Osiris. The marriage corresponds to the initiation; the trip is an allegory of the sufferings ritually enacted in this life. Because other gods emerge next to Isis, he assumes a syncretism of Artemis, Hera, and Isis as well as an additional redaction in the case of Helios. The lack of motivation, according to Merkelbach 1962, is based on the mysterious character of the writing that is understandable only for the initiates. However, the religious meaning is hidden so that the uninitiated can enjoy the “surface meaning” (ibid. 90:125n2; Merkelbach 1995:335, 338), i.e. the literary product.

[ back ] 48. We can define the presented spaces as mythical according to the criteria of Hübner 1985:170. According to Foust 1981 Frank’s spatial form (Frank 1945), which has been invented for the modern novel, but also be applied for the ancient novel, is close to the structures of myth.

[ back ] 49. On the dream in the novel see Bowersock 1994:77–98 and Doody 1996:405–420. For Habrokomes’ dreams see now Liatsi 2004.

[ back ] 50. Scarcella 1979:94–95, 100.

[ back ] 51. Kytzler 1996:343.

[ back ] 52. Of course, the trip can always be read in light of the Odyssey, which frequently functions as a hypertext in the novel. The wrath of Poseidon is here transferred to Eros; the adventures that the hero experiences and then reports serve as a homodiegetic analepsis to the Odyssey; here, on the contrary, they are spread out as a story between autobiography and fiction.

[ back ] 53. On Hippothoos see now Watanabe 2003.

[ back ] 54. Fusillo 1989:123 points out that the relationship of the dream to the remaining plot remains somewhat unclear in Xenophon, either because of a lack of elaboration or because of a certain autonomy of popular elements.

[ back ] 55. See the Novel of the Ass that likely has come to us in form of Ps.-Lucian’s epitome with the title Lucius or the Ass and in the more fully detailed version of the Metamorphoses of Apuleius, enriched by elements of the cult of Isis.

[ back ] 56. On the horse as a key symbol of the young girl on the threshold of womanhood see Alcman’s Louvre Partheneion fr. 1 Davies. On Agido and Hagesichora as possible embodiments of the Leucippides (‘white horses’) see among others Nagy 1990:346. See also below n62.

[ back ] 57. Laplace 1994:466.

[ back ] 58. Habrokomes experiences a somewhat similar situation in the story. His love is also threatened by rivals who suffer a shipwreck, and he thinks the girl is likewise dead.

[ back ] 59. See Jakobson 1971, esp. 243 and Iser 1983:125–126; Iser 1979:300.

[ back ] 60. See Dowden 1999 and Lalanne 2006. See now Bierl 2007. See also Bierl 2001, index s.v. ‘Hochzeit’.

[ back ] 61. We can recognize this also by means of the oneirata explicity described in our novel. See also Walde 2001 and the above n49.

[ back ] 62. Lacan 1966:260. On Lacan see Frank 1983:367–399; Welsch 1996:275–290. The remarks by Schmitz 2002:222–224 are insufficient. On the imaginary, desire, and intermediate corporality of Merleau-Ponty in connection to Lacan see Tholen 2002:61–92, 139–146. On the horse (see also above n56) in Doubrovsky see Tepperberg 1997. With Lacan we could consider the initial pride of Habrokomes as a narcissistic phase of moi that remains absolutely illusionary. The build-in gap is expressed in love. Through this, je experiences itself as the true other and decentralized self in the stream of signifiers.

[ back ] 63. Jakobson 1971:258. Brooks 1984, esp. 37, 55–56, 58–59, 105, 234, 278–279 links narration and plot with Lacan’s concept of desire. See the criticism in Lowe 2000:14. Such an approach would make any formal definition of plot impossible. However, I think that such a view has a great heuristic value in the love novel, as love plays such a central role. For criticism on Lacan’s linguistic construct see Görling 1997:94–130 from a cultural and psychoanalytic perspective. According to his concept of heterotopia love is wish and metaphor, not desire and metonymy. Metaphor would manifest itself in body motion and transfer in space in an oscillating movement between euphoria and melancholy.

[ back ] 64. See Gronemann 1999.

[ back ] 65. See de Man 1979; see esp. Menke 1993:39: “In der Autobiographie und dem Text als ‘Autobiographie’ instituiert sich der Dichter selbst, indem er sich selbst ein Epitaph setzt, lesend/schreibend den Text und sich als ‘Stimme’ des Textes im Text monumentalisiert, der ihm als Prosopopöie Figur oder Gesicht verleiht und es (eben damit) verwischt oder entzieht.” In order to avoid misunderstandings, of course, I am conscious of how questionable it can be to interpret ancient literature on the basis of modern and postmodern thinking. But once more we can see that the difference between the other of antiquity and the present can be partly very narrow, but this insight is concealed by a thick layer of ideas and preconceptions which are characteristic of classical modernity.

[ back ] 66. On the oracle see Rohde 1876:424–425; Gärtner 1967:2066–2067; Ruiz-Montero 1994:1098–1101.

[ back ] 67. In general the oracle is fulfilled. Bandits and pirates appear immediately afterwards; the motif of τάφος—θάλαμος and of πῦρ ἀίδηλον is often present. The ships burn; both hero and heroine undergo an apparent death (poison, pit, Ares’ victim, Habrokomes’ death sentence on the Nile banks) and they have a happy fate at last, because they finally return to Ephesos. See also Kerényi 1927:62.

[ back ] 68. There is a νοῦσος and a λύσις, too, for both. The marriage represents the later, of course, the desired goal. Before this, however, the youth must pass through the painful rite de passage of δεινὰ πάθη. The ἔργα can be the ritual actions as well as the works of love themselves, the realization, as it is later described, on the wedding night (τῶν Ἀφροδίτης ἔργων ἀπήλαυον, 1.9.9). The flight across the sea can naturally be taken literally, as the fathers do; but it is also about the fight against Eros. This causes mania and lyssa (λυσσοδίωκτοι): the youth is pursued by madness, is drawn towards and longs after the other. In this the young man crosses every border, the sea itself (φεύξονται ὑπεὶρ ἅλα). At the same time flight is a separation from one’s own oikos, the ritual of separation. Love is always a chain (δεσμά), a magical power that binds another person (καταδεσμός). The sea is a metaphor for the expanse entered into by the young man. Water is associated with tears, among others, that soon flow freely in the next scene (δάκρυα, 1.9.2). Marriage is frequently associated with a rite de passage in Greek, like burial (Seaford 1987); a part of that is the painful separation from the former world. The process is especially painful for the young woman, since she goes into the house of her husband and leaves all social bonds behind her. Fire belongs likewise to love; the young persons burn with love (καιόμενοι, 1.9.1). Fire is ἀίδηλον; it makes unseen and destroys. Love comes over the eyes and makes the sufferer blind. At the same time the word points to Hades Ἀίδης, the unseen. At the end, namely in the final reunion, they accept Aphrodite’s joyful gifts (ὄλβια δῶρα). Isis, as the god of marriage, can grant this and both hero and heroine can correspondingly thank the goddess. After the successful completion of the transition ritual a better fate awaits them (ἀρείονα πότμον ἔχουσιν). On the sea and storm as metaphors for love see Laplace 1983:317.

[ back ] 69. The scene appeared so intensive and the exchange of souls so unnatural to Kerényi 1927:42 that he connected the embrace of Isis and the dead Osiris with this.

[ back ] 70. Foley 1997.

[ back ] 71. On offerings of hair as a sign of initiation and on recognition based on a hair offering see Aeschylus Choephoroi 168–169, 226 and Bierl 1994:152n27.

[ back ] 72. See the epigrams integrated into the text: 1.12.2 (consecration of a panoply); 3.2.13 (Hippothoos’ grave inscription for Hyperanthes); 5.11.6 (Anthia’s hair-offering). Similar is the remark (5.15.2) that Anthia and Habrokomes consecrated a book.

[ back ] 74. On the custom of Egyptian mummification as a reflection of the living world see Griffiths 1978:433–437.

[ back ] 75. On the ‘weaving’ (ὑφαίνειν) of songs und texts see Nagy 1996:64–65.

[ back ] 76. On the ‘speaking names’ see Kerényi 1927:170–172; Hägg 1971b; Griffiths 1978:432 with Egyptian explanation of Araxos and Rhenaia; Ruiz-Montero 1994:1007–1009. See Bierl 2001, index s.v. ‘Name als Programm’.

[ back ] 77. On this see Ruiz-Montero 1994:1108 and Hägg 1971b:38 with n25.

[ back ] 78. The fact that Hippothoos owns a horse (2.14.5) emphasizes the ‘glissement des signifiants’.

[ back ] 79. It is worthwhile to consider the drift of signifiers more exactly by taking up the theme of the dogs. Dogs, like robbers, represent the sexual threat that makes the gap to the beloved even greater. At the end of book 3, after the shipwreck, Habrokomes is sold to Araxos by Egyptian robbers. His wife Kyno desires him and he nearly responds to her overtures. But when she kills her husband, things become too much for him and he flees. For this Kyno accuses him of the crime (3.12). The prefect of Egypt learns the truth after many attempts to put Habrokomes to death and finally has Kyno crucified (4.4.2). After a long interruption the name is again brought up. Then the “dog” motif leads directly into the episode with Amphinomos, who feeds the dogs (4.5–6). After the inserted story of Aegialeus the story of Amphinomos’ falling in love with Anthia resumes. He can leave Hippothoos and the girl responds to his promises not to touch her until she would agree in free will. Both set off for Koptos, but the dogs do not disappear: “The dogs, however, did not leave them, for they had become close to her and love her.” (5.2.5) There they care for the dogs with sufficient food (5.2.6). The dogs are turned into, so to speak, the externalized male threat. First, in the meat they are given a substitute for their basic instinct. Finally they follow the new pair—a hint at her consent in “tamed” sexual services. Merkelbach 1995:361n2 thinks that the dogs might allude to the dog-headed Anubis who accompanies Isis on her search for Osiris (see ibid. 100–101).

[ back ] 80. See Puiggali 1986, esp. 328.

[ back ] 81. See Dowden 1999 and Lalanne 2006. Such a space becomes, according to Görling 1997, a heterotopos and “space of passages” (185) of liminality acted out on the body (126–128).