Hermann, Pernille, Stephen A. Mitchell, and Jens Peter Schjødt, eds., with Amber J. Rose. 2017. Old Norse Mythology—Comparative Perspectives. Milman Parry Collection of Oral Literature 3. Cambridge, MA: Milman Parry Collection of Oral Literature. http://nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:hul.ebook:CHS_HermannP_etal_eds.Old_Norse_Mythology.2017.

Methodological Challenges to the Study of Old Norse Myths: The Orality and Literacy Debate Reframed

Source evaluation

Oral-Derived texts

The resigned conclusion of this passage about the elusory character of eddic poems may very well be an implication of a lack of methodological concern and of a textually-biased view of the texts. Implicit to the questions of age and provenance are text-bound ideas of “works” as finalized textual units, and ideas about the possibility of exact dating and arranging the poems in chronological order are organizing principles that are not readily adaptable to oral texts nor, most likely, to oral-derived texts.

Text-Context

Parallel with an increased awareness of “performance” and “living orality”, it becomes relevant not merely to reconstruct the myths themselves, but also to recontextualize them. Thus, in acknowledging that in an oral situation, meaning emerges as much from the context as from the text itself, it becomes increasingly important to scrutinize in which ways it is possible to recontextualize the myths.

However, some new pathways have been laid out (see Jochens 1993), implying that dichotomizing tendencies that have otherwise been dominant, say, between genres like history and fiction (Clunies Ross 1998; Hermann 2010) or between pagan traits and Christian influence (Lönnroth 1969; Vésteinn Ólason 1998), are not as firm as they may appear. For instance, Jürg Glauser has proposed that less focus on genre distinctions, that is, on textual classification and chronology, as well as an increased focus on alternative “concepts of text” (Glauser 2000a, 2007) may break down classifications that otherwise have guided our understanding of the source value of the texts. Studies in saga-texts increasingly turn attention to the number of ways in which these texts are discursively indebted to cultural, historical, and ideological forces at the time of each text witness, as well as to the reception of texts (Quinn and Lethbridge 2010). In having other foci than those literary approaches that emphasize author, literary borrowings, and the question of origins, future studies that follow up on such pathways may very likely bring to light new aspects of the textual material, aspects that will also inspire the study of myths in context.

Myth performance

Books with non-ecclesiastical content were also read aloud in front of audiences. It has long been emphasized, and it is generally accepted, that this was the case for saga-texts; and it has been argued as well that eddic poems were intended to be read out loud and possibly even to be acted dramatically (Lönnroth 1979; Mitchell 1991; Gunnell 1995a, 1995b; Mundal 2010). This argument shows that when transferred to written form, the narrative material was potentially realized and received in a context that retained dimensions that otherwise confine themselves to oral situations. This observation thus locates the written texts in multi-media and multidimensional situations, where books and visible signs on the page would have been accompanied by such features as voice and bodily orientation.

Words and images

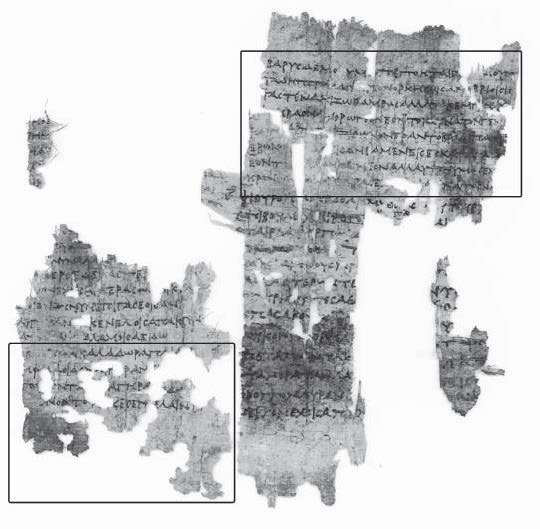

Figure 1. The dialogue between Gangleri and Hár, Jafnhár, and Þriði. Uppsala University Library, MS DG 11.

Figure 2. Figures with hand gestures. Uppsala University Library, MS DG 11.

Diachronic and synchronic approaches

This comment points to the existence of myth multiforms. Obviously, prose and poetry represented the myths differently. Not only would allusive poetry have relied to a higher extent than prose on foreknowledge, that is, on actively participating recipients who shared a collective memory of the mythic tradition, but also within each genre, differences would have existed. This is seen, for instance, in comparing the two existing prose versions of Baldr’s death, namely Snorri’s and Saxo’s, in the Edda and the Gesta Danorum respectively. Whereas the first represents the myth in the context of a mythography, the latter incorporated it in a historiography. The ideologies of the writers, as well as their thematic and stylistic choices, actually resulted in two different literary treatments of the same myth (e.g., Clunies Ross 1992).

Works Cited

Primary sources

Secondary Sources

Footnotes