Use the following persistent identifier: http://nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:hul.ebook:CHS_Petropoulos.Heat_and_Lust.1994.

Heat and Lust

Hesiod’s Midsummer Festival Scene Revisited

J.C.B. Petropoulos

ἄστρων κάτοιδα νυκτέρων ὁμήγυριν, καὶ τοὺς φέροντας χεῖμα καὶ θέρος βροτοῖς λαμπροὺς δυνάστας, ἐμπρέποντας αἰθέρι ἀστέρας …

Aeschylus Agamemnon 4-7

Ραχοῦλες, εἶμαι ὁ πιστικὸς τῆς ἥμερης ἀρνάδας, ὀργώνω, σπέρνω, ἱδροκοπῶ, τοῦ κάμπου δουλευτής, καὶ λούζω τὸ τραγούδι μου στῆς δροσοπρασινάδας τὰ δάκρυα καὶ στὰ δάκρυα τῆς δύσκολης ζωῆς …

Kostis Palamas, Askraios, vv. 21-24

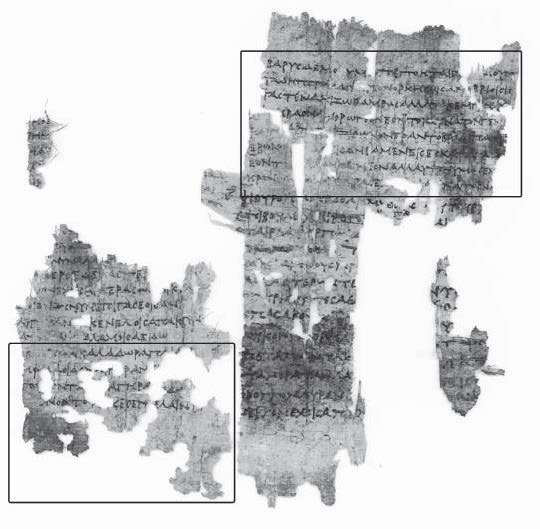

Jacques Villon (1875-1963). “Works and Days,” copperplate engraving. Courtesy of the Director and Board of Trustees of the Museum-Library Tériade (Varia, Mytilini).

Preface

Διὰ τί ἐν τῷ θέpei οἱ μὲν ἄνδρες ἧττον δύνανται ἀφροδισίαζειν, αἱ δἐ γυναῖκες μᾶλλον, καθάπερ καὶ ὁ ποιητὴς λέγει ἐπὶ τῷ σκολύμῷ … ;

(pseudo-?) Aristotle Problems 4.25.879a26-28

Why are men less capable of sexual relations in summer, whereas women are more so, just as the poet [sc. Hesiod] also says of the time when the golden thistle flowers … ?

This monograph was written in response to two questions which exercised me when some time ago I reread Hesiod’s description of midsummer in Works and Days: precisely why are his women wanton at this season? And how might one otherwise explain the similarly worded passage in Alcaeus (fr. 347a [LP]) than as a transparent imitation or adaptation? To answer both questions—and the one seemed to germinate out of the other—I found it necessary to undertake nothing less than a survey of connections between certain agricultural themes in Hesiod (and Alcaeus) and modern Greek agrarian practices and the relevant folk-songs. As will rapidly become apparent, my method is that of a classicist who seeks to reconstruct—in reverse chronological order—certain aspects of the social and agrarian context of Works and Days. The recourse to “backward extrapolation” does not even remotely imply across-the-board immutability of the past; I am well aware of the many discrepancies between the respective ecologies and technologies of Hesiod’s day and those of modern times. As I see it, the mainspring of this critical analysis of popular culture in Hesiodic Greece resides in the infinitely involved task of finding ways to unearth those practices and cultural assumptions of archaic (and classical) Greece which may arguably resemble conditions preserved in the ethnographic record of more recent times. The implications of these points of contact will perhaps most interest classicists, social anthropologists, and historians of popular culture.

The account of modern practices is of interest in its own right; to classicists in particular such an account may even prove illuminating, or at least thought-provoking, especially if it prompts new and very plausible interpretations of an ancient passage. Since the time of Eustathius of Thessalonica (at the latest) classical scholars and other specialists have resorted largely to parallels from later Greek folk-song and folk practice for this very reason. And of late the comparativist tack has been followed, often with attractive results, by the discipline of ethnoarchaeology.

The modern field data here presented are drawn from a wide variety of geographical regions of Greek-speaking society and span the period roughly from 1860 to 1960. Rather than impede my analysis with a thick cloud of necessary caveats and qualifications, I have used the “historical” present tense throughout this work, even where (in some cases) this may seem anachronistic nowadays, and I have tried throughout to limn a generalized picture of farming events without, however, adopting the outlook of a heavy-handed uniformist. The comparative ethnographic models which will emerge purport never to be too wide of the mark and to be representative enough for at least a few broader insights into farming life, present and past, not to come amiss. With the help of these models, specialists and non-specialists alike will, I hope, be better equipped to summon to mind the seasonal signposts and songs, the activities and moods, the timing and rhythms of the harvest in archaic and classical Greek society. Perhaps, as a result of this comparative evidence, readers will also regard the seeming coincidences between Hesiod and Alcaeus in a different light.

I must now thank those who were kind enough to give practical help and advice at various stages of this book’s composition. A grant from the Democritean University of Thrace covered a portion of my typing expenses; Ms. Ann Blasingham expertly formatted and typed successive drafts, including the camera-ready copy. The directors and staff of the Gennadios Library and the libraries of the American School of Classical Studies and the British School at Athens provided courteous assistance and an agreeable environment in which to work. It would not, I think, be out of place to cite the stimulus, the humor, and φιλοξενία afforded me not only by colleagues but also by the students who attended my class on Works and Days at the University of Crete at Rethymno in the spring of 1991.1 am grateful also to Dr. John Bintliff, co-director of the Cambridge-Bradford Boeotia survey, for his comments on an earlier version of chapter 4, and to Professor Margaret Alexiou for sharing her insights into oral poetry. Emeritus Professor Demetrios Loukatos was, as always, munificent with his deep learning and love of Greek folk tradition. Sir Kenneth Dover and Professor Ruth Scodel are especially to be thanked for their rigorous criticism and salutary suggestions.

It is, lastly, both an honor and a pleasure to thank the general editor of this series, Professor Gregory Nagy. Not only did he take enormous care in reading and improving what turned out to be a long-suffering typescript; his own work has over the years taught me more and more the meaning of openmindedness in classical studies. To his relentless intellectual finesse and unremitting support I owe more than even he must suspect.

I dedicate this book to the farmers (male and female) of Thrace.

Democritean University of Thrace,

Alexandroupolis

February 1, 1993

Alexandroupolis

February 1, 1993