Use the following persistent identifier: http://nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:hul.ebook:CHS_AlexiouM.Ritual_Lament_in_Greek_Tradition.2002.

6. The classification of ancient and modern laments and songs to the dead

The ritual lament of the women: thrênos, góos, kommos

The men’s part: praise of the dead

νήσοις δ’ ἐν μακάρων σέ φασιν εἶναι,

ἵνα περ ποδώκης’Αχιλεὺς

Τυδεΐδην τέ φασι τὸν ἐσθλὸν Διομήδεα.

but gone, men say, to the Isles of the Blest,

where swift-footed Achilles,

and brave Diomedes, Tydeus’ son, are said to be.

ἀντὶ γάμο | παρὰ θεον τοῦτο | λαχοσ’ ὄνομα.

for the gods gave me this name instead of marriage.

Θουριέας ξείνηι τῆιδε κέκευθα κόνει [15a]

Εὔκλειτον, τὸμ πρῶτ[ο]ν δὴ κατετύψατο μήτηρ

ὀκτωκανδεχέτη παῖδα καταφθίμενον,

δωδεχέτη δὲ μετ’ αὐτὸν ἀνέκλαυσεν Θεόδωρον

αἰαῖ τοὺς ἀδίκως οἰχομένους ὑπὸ γῆν.

I lie hidden in this foreign dust of Thouriea.

Eukleitos died first, a boy of eighteen years,

and his mother beat her breast for him;

after him she wept for twelve-year-old Theodoros.

Alas for those who are gone beneath the earth unjustly!

Ἀμμία, θυγάτηρ πινυτή, πῶς θάνες ἤδη;

τί σπεύδουσα θάνες ἢ τίς (σ)ε κιχήσατο μοιρῶν;

πρίν σε νυνφικὸν ἰς(σ)τέφανον κοσμήσαμεν [ἐ]ν θαλάμοισιν,

πάτρην σε λιπῖν πενθαλέους δὲ τοκῆας·

καὶ θρήνη]σε πατὴρ κ(αὶ) πᾶσα πατ[ρὶς] κ(αὶ) πότνια μήτηρ

τὴ[ν] σ[ὴν] ἀωροτ[ά]τ[η]ν κ(αὶ) ἀθαλάμευ[τον] ἡλικίην.

Why did you hasten to die, or which of the Fates overtook you?

Before we decked you for the bridal garland in the marriage chamber {106|107}

you left your home and your grieving parents.

Your father, and all the country, and your mother lamented

for your most untimely and unwedded youth.

These inscriptions are an invaluable source of evidence for the present study, since they are probably the closest reflection of popular language, style and thought in antiquity that we possess, although we cannot be sure of the exact manner of their composition. The vast majority are anonymous, written for a wide range of people from differing social classes from the whole of the Greek-speaking world. The large number of common ideas and formulae, many derived from classical literature, others found also in the epigrams of the Anthology, points to a degree of standardisation. It has even been argued that the stone-cutters used manuals of stock formulae from which the bereaved might choose their themes, and that the inscriptions are therefore minimally creative. [16] But in the absence of any specific evidence for the use of such manuals in Greek, it would surely be a mistake to dismiss them as entirely derivative: within the bounds of the convention, ideas, language and style vary considerably according to the time and place of composition, and according to the status of the deceased. The inscriptions afford us a unique insight into a complete cross-section of society; and it is frequently the more humble, semi-literate examples which offer the most valuable evidence. Finally, the striking similarities of formulae and style in these inscriptions and some of the modern moirológia, discussed in Part III, may throw some light not only on the origins of the modern laments, but also on the traditional nature of the inscriptions themselves.

The growth of a new terminology

μάτηρ ὠκύμορον παῖδ’ ἐβόασε φίλαν,

ψυχὰν ἀγκαλέουσα Φιλαινίδος, ἂ πρὸ γάμοιο

χλωρὸν ὑπὲρ ποταμοῦ χεῦμ’ Ἀχέροντας ἔβα.

in tears cried out for her dear short-lived child,

invoking the soul of Philainis to return, who, before wedlock,

passed across the pallid stream of Acheron.

But it was not restricted to literature. The verb ἀνακαλεῖν, as we have seen in chapter 4, was commonly used for the refrain invoking the dying god by name to rise again, an indispensable element of the ancient lament for gods. Its importance may be judged by the use of the cognate forms ἀνακλήθρα and ἀνακληθρίς for the stone on which Demeter is said to have sat when she invoked Persephone. The ritual enactment of this anáklesis was continued by the women of Megara until Pausanias’ day. [21] The verb form is used for the Virgin’s invocation to the dying Christ, and the noun form anakálema later denotes the lament for the fall of Constantinople. [22]

she wept for all at the tomb, all of them she invoked.

The song to Fate—origin of the modern moirológi?

Ἀγαμέμνονός τε μοῖραν. ἀρκείτω βίος.

ὲμὸν τὸν αὐτῆς. ἡλίου δ᾽ ἐπεύχομαι

πρὸς ὕστατον φῶς τοὺς ἐμοὺς τιμαόροις

ἐχθροὺς φανεῖσι δεσποτῶν τίνειν ἴσα {112|113}

δούλης θανούσης, εὐμαροῦς χειρώματος.

ἰὼ βρότεια πράγματ’ · εὐτυχοῦντα μὲν

σκιά τις ἂν τέρψειεν εἰ δὲ δυστυχοῖ,

βολαῖς ὑγρώσσων σπόγγος ὤλεσεν γραφήν.

inside the house. Enough of life!

Yet one word more, my own dirge for myself.

I pray the Sun, on whom I now look my last,

that he may grant to my master’s avengers

a fair price for the slave-girl slain at his side.

O sad mortality! when fortune smiles,

a painted image; and when trouble comes,

one touch of a wet sponge wipes it away. [28]

It is true that Cassandra’s position was a peculiar one; but her protest against fate and farewell to life, both essential parts of her lament for herself, are themes which constantly recur in tragedy. Further, the lament of the tragic hero or heroine for his own fate or death accounts for a high proportion of the laments in Greek tragedy. Other tragic figures who sing their own dirges include the Suppliant Women in Aeschylus, Ajax, Jokasta, Oedipus, Antigone, Deianeira and Philoktetes in Sophokles, and Alkestis, Hekabe, Polyxena, Medea, Phaidra, Andromache and Iphigeneia in Euripides. Their laments contain a striking number of common formulae and themes; and in all, moîra and týche are of the utmost importance. [29] This suggests a basis in popular belief outside the confines of tragic drama.

μοιρολογεῖ τραγώδημαν, τούτους τοὺς λόγους λέγει·

(Ἰδοὺ τὸ μοιρολόγημαν τοῦ ξένου Καλλιμάχου

τοῦ μισθαργοῦ, τοῦ κηπουροῦ, τοῦ νεροκουβαλήτου.)

—Στῆσον ἀπάρτι, Τύχη μου, πλάνησιν τὴν τοσαύτην …

καὶ τί παράλογον πρὸς σὲ ποτέ μου ἐνεθυμήθην …;

he sings a lament, and says these words:

(Behold the lament of Kallimachos, far from home,

the labourer, the gardener, the water-carrier.)

—Cease now, at last, my Fortune, such great deceit …

Fortune, how have I wronged you, my Fortune, what have I done,

and what unreasonable thought have I ever entertained against you?

The connection here between lamentation and Fate could not be more plain. Its popular character is further demonstrated by similar reproaches in the modern folk laments: [43] {115|116}

κι ἂν λάχη καὶ ξενιτευθῶ, θάνατο μὴ μοῦ δώσης.

but if it is my lot to go, do not let me die there.

Moirológia for departure from home, change of religion, and marriage

ἄχ, ἡ ξενετιὰ σᾶς χαίρεται τὰ νιάτα τὰ γραμμένα·

ὄχ, ἀνάθεμά σε, ξενετιά, ἐσὺ καὶ τὰ καλά σου,

ἄχ, μᾶς πῆρες ὅλα τὰ παιδιὰ μέσα στὴν ἀγκαλιά σου!

Ach, my children far from home, there where you are in foreign lands.

Ach, foreign lands enjoy your allotted youth.

Och, a curse upon you, foreign lands, you and your good things!

ach, you have taken all our children into your embrace !

One reason for the peculiar intensity of these laments is the fear of death in foreign lands, which is also known to have existed in antiquity: [60]

ὁποὺ πεθαίν’ν στὴν ξενιτιὰ καὶ στὰ νοσοκομεῖα.

who die in foreign lands and who die in hospitals.

σήμερα ξεχωρίζουνε ἀιτὸς καὶ περιστέρα,

σήμερα ξεχωρίζουνε παιδάκια ὀχ τὸν πατέρα.

Τέσσεροι στύλοι τοῦ σπιτιοῦ, ἔχετε καλὴ νύχτα,

καὶ πέστε τῆς γθναίκες μου, δὲν ἔρχουμαι ἄλλη νύχτα.

Τέσσεροι στύλοι τοῦ σπιτιοῦ, ἔχετε καλὸ βράδι,

καὶ πέστε τοῦ πατέρα μου δὲν ἔρχουμ᾽ ἄλλο βράδι.

today the eagle and the dove take leave,

today children take leave of their father.

Four columns of the house, I bid you goodnight,

tell my wife I’ll come at night no more;

four columns of the house, I bid you good evening,

tell my father I’ll come at evening no more.

Σήμερο μαῦρος οὐρανός, σήμερο μαύρ’ ἡμέρα,

σήμερ’ ἀποχωρίζεται μάνα τὴ θυγατέρα.

Ἄνοιξαν οἱ ἑφτὰ οὐρανοὶ τὰ δώδεκα βαγγέλια,

κι ἐπῆραν τὸ παιδάκι μου ἀπὸ τὰ δυό μου χέρια.

Μισεύγεις, θυγατέρα μου, καὶ πλιὸ δὲ θὰ γελάσω,

Σάββατο πλιὸ δὲ θὰ λουστῶ οὐδ’ ἑορτὴ θ’ ἀλλάξω.

today a mother takes leave of her daughter.

The seven skies have opened the twelve gospels, [64]

and have taken my child from out of my arms.

You are leaving, daughter, and I shall never laugh again,

nor wash on Saturdays, nor change for a festival.

κι ἂ κλαίω ποιο πειράζω;

—Σέρνε με κι ἂς κλαίω κιόλας.

If I weep, whom do I harm?

Drag me away, though I weep still.

Or at the last moment she begs her mother to hide her. This resistance, suggesting, beneath the convention, her real fear of leaving girlhood, brings her mother to her senses:

τὴ σκάλιζα, τὴν πότιζα, τὴν εἶχα γιὰ δική μου.

Μά ’ρθε ξένος κι ἀπόξενος, ἦρθε καὶ μοῦ τὴν πῆρε. {121|122}

— Κρύψε με, μάνα, κρύψε με, νὰ μὴ μὲ πάρη ὁ ξένος.

— Τί νὰ σὲ κρύψω, μάτια μου, ποὺ σὺ τοῦ ξένου εἶσαι·

τοῦ ξένου φόρια φόρεσε, τοῦ ξένου δαχτυλίδια,

γιατὶ τοῦ ξένου εἶσαι καὶ σύ, κι ὁ ξένος θὰ σὲ πάρη.

I weeded it, I watered it, and it was all my own.

But a stranger, yes a stranger came and took it from me.

— Hide me, mother, hide me, so the stranger cannot take me.

— How can I hide you, dear one, now you belong to him:

wear the stranger’s clothes, wear the stranger’s rings,

for you belong to him, and he will take you.

Similarly, in a funeral lament from Tsakonia, the dying girl sees Charos approach, and begs her mother to hide her in a cage, in a chest, among the basil and balsam plants; but her mother replies sternly that he will not, that she gives her over to Charos (Laog (1923) 40). The allusive quality of these songs, where the imagery of the funeral laments, especially for those who died young, is imbued with the imagery of the wedding songs, may owe something to the antiquity in Greek tradition of the theme of death as marriage, which can be richly illustrated from tragedy, from the epigrams of the Anthology, from rhetorical and narrative works, and, most abundantly, from the funerary inscriptions. [65]

Moirólgia for the dead

ἦταν βρυσούλα μὲ νερὸ καὶ δέντρος ἰσκιωμένος,

ποὺ κάθονταν στὸν ἴσκιο του ἀδέρφια καὶ ξαδέρφια, {122|123}

κάθονταν καὶ ὁ ἄντρας της μαζὶ μὲ τα παιδιά της.

Τώρα ν ἡ βρύση στέρεψε κι ὁ δέντρος ξεριζώθη.

there was a fountain with water and a shady tree,

where brothers and cousins would sit in its shade,

where her husband would sit and with him her children.

Now the fountain has dried up, and the tree is uprooted.

In Mani, the mourner may begin with a stereotyped, proverbial opening in fifteen-syllable verse, and continue with a direct address, improvised in eight-syllable rhyming couplets:

τ’ ἀδέρφια σκίζουν τὰ βουνά, ὅσο ν’ ἀνταμωθοῦνε.

Ἔ, ἀδερφούλι μου χρυσό,

γι’ ἄνοιξε τὰ ματάκια σου …

Brothers rend mountains asunder until they meet again.

É, my golden brother,

open your eyes now!

The improvisations at the laying-out are usually long, lyrical reproaches from the next of kin, which follow a traditional pattern according to the person addressed, whether a mother, father, husband, brother or child (Laog (1960) 366-74, 379). Sophia Lala of Samarina, well known as an expert mourner, complained to me in 1966 that many women did not bother to observe the correct distinctions in their laments, and would sing the first thing that would come into their heads, whereas if she was invited to lament at a funeral, she would always think carefully before she started what type of lament was proper to the occasion. In Mani, where the custom of lamentation is particularly vigorous, the mourner introduces into her improvisation many specific details from the past: in a lament for a young girl who died of leukaemia after graduating in Greek literature, her aunt recounts to her in detail how many doctors were consulted, and how many friends came to give blood, in a vain attempt to save her life (Laog (1960) 396.3, 5-10).

| — Ἔ, Πότη μου, ἄκου νὰ σοῦ πῶ, | — E, my Potis, listen to me, |

| κλαίγοντας παρακαλετῶ, | weeping I beg you, |

| μὴ φύγης, μὴν ἀναχωρῆς, | do not go, do not depart, |

| μὴν πᾶς ἐσὺ γιὰ νὰ κλειστῆς | don’t get yourself shut up |

| στὸν Ἄδη καὶ στὴν κάτω γῆ. | in Hades and the Underworld. |

ἀποὺ λου(γ)άριαντζα νὰ ζῶ, νὰ θάψω τὸ παι(δ)ίμ μου.

where I hoped to live, to bury my child.

Young Stasia, three months buried, begs Charos to let her join her brothers, who have just come home from abroad, but Charos replies sternly that she will see them only when they come to light candles on her grave (ibid. 188.9). A Cypriot mother accuses Charos in a formula to that of the ancient inscriptions: [68]

ποὺ ἦταν τὸ καμάριν μου, ποὺ ἦταν ἡ ζωή μου.

who was my pride, who was my life.

θρήνων τ’ ὀδυρμοὶ μοῦσά θ’ ἢ λύπας ἔχει.

and the weeping of dirges, and the sorrowful Muse.

It is echoed in many laments today. A Maniot woman sings:

κάλλιό ᾽χω νὰ μοιρολογῶ,

παρὰ νὰ φάω καὶ νὰ πιῶ.

Ι would rather sing dirges

than eat or drink.

ποὺ πλώναμε τὰ ροῦχα μας ἀπάνω τσαὶ μυρίζα.

where we hung our clothes to take its scent.

Σφαῖρα ’ναι τοῦτος ὁ ντουνιὰς κι ὅλο στριφογυρίζει,

ἄλλους τοὺς ἀνταμώνει ὁ Θιὸς κι ἄλλους τοὺς ξεχωρίζει.

some God brings together, others he sunders.

κι ἂν δὲ σὲ κλάψη ἡ μάνα σου, ὁ κόσμος δὲ δακρύζει.

and if your mother does not weep for you, the world sheds no tears.

Finally, one of the laments I recorded in 1963 from the village of Rhodia in Thessaly, sung by a group of men in chorus to the slow, monotonous and mournful tune characteristic of the Thessalian plain, approaches the spirit of some of the ancient elegiacs. [75] As the words indicate, it is appropriate to a gathering of men:

ὡρὲ τοῦτον τὸν χρόνον τὸν καλόν, τὸν ἄλλον ποιὸς τὸν ξέρει;

ὡρὲ γιὰ ζοῦμε γιὰ πεθαίνουμε γιὰ σ᾽ ἄλλον κόσμον πᾶμε. {127|128}

Joyful company, rejoice that we may enjoy

this good year, who knows what the next will bring?

whether we live or die or go to the other world.

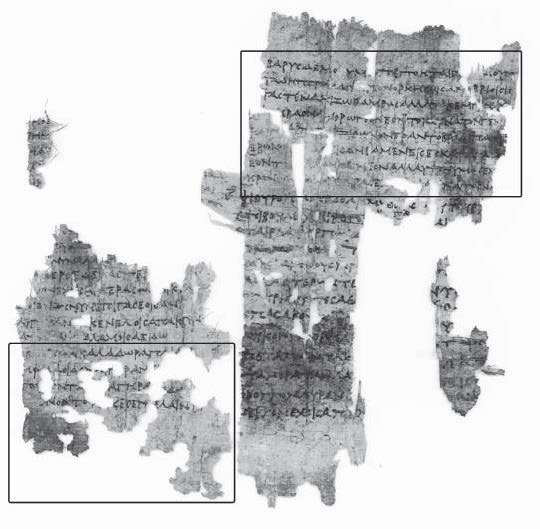

Figure 1. Black-figure loutrophóros amphora by the Sappho Painter, c. 500 B.C. Próthesis: the dead man is laid out on a bier, his head resting on a pillow. A child is standing at the head. To the left are six mourning women in varying attitudes of lamentation, the first with her right hand on the dead man’s head, the others with their left hands to their heads and their right arms outstretched. {129|130}

Figure 2a. Panel-painting by an unknown Cretan artist, early seventeenth century. Thrênos: Christ has been taken down from the cross. The Virgin holds Christ’s head with both hands. John is in the centre, and probably Joseph of Arimathaea at the feet; behind stands Nikodemos, holding the ladder. Behind are six unidentified mourning women. The black triangles beneath the eyes of all figures except for Christ, indicating grief, are a typically Cretan detail. Beneath Christ is a bag with the nails and an ointment vessel.

Figure 2b. Panel-painting, dated 1699. Thrênos: Christ has been taken down from the cross. The Virgin holds his head and weeps, comforted by two women, while a third pulls her hair with both hands. There is no cross in the background, but the presence of the moon, stars, and dimmed sun is probably an intrusion from the Crucifixion scene. {130|131}

Figure 3a. Elderly women at the tomb lament antiphonally for a child, probably at a memorial after the funeral, since the cross has been erected. On the grave are placed fruit and food, which are shared out among the women after the lament is finished.

Figure 3b. Three women lament at the tomb, which is covered with fresh flowers, after the burial. The bereaved widow is at the head of the tomb, and two relatives on the left. {131|132}

Figure 4a. Women at the cemetery lament during the memorial held on the fortieth day after the death of a young man, killed by lightning. The whole village took part in the memorial, buy only the women entered the cemetery for the lament, which lasted for over an hour.

Figure 4b. Same occasion as 4a. A women hands round wine, fish, meat and sweetmeats to the mourners after the lament is finished.

Footnotes